I’ll be teaching a course on the prime (pre-1984) of David Bowie for the first time starting mid-October, and spent a lot of time preparing the material during the summer. As I got my class together, I’ve heard and seen a lot more David Bowie than I have for a while.

There’s been a lot written about David Bowie. Still, there are a few aspects of his work that aren’t discussed much. Like I did when I offered a Doors course a few years ago, and when I offered a Pink Floyd course starting just a month ago, I’m going over some of them with this blogpost.

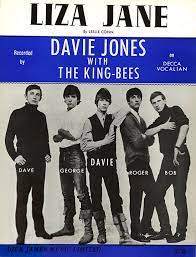

1 .David Bowie as cover artist. In his first couple decades, almost all of Bowie’s records featured original material, his 1973 all-covers Pin Ups album being a notable exception. But he’s often dotted his discography with cover versions. Indeed his very first single as singer with the King Bees, “Liza Jane”/ “Louie Louie Go Home,” had two non-originals, the first being a sub-early Rolling Stones-style adaptation of a bluesy spiritual (credited to his manager of the time, Leslie Conn), the B-side being a rather obscure “answer” record to “Louie Louie” by Paul Revere & the Raiders. The A-side of his second single was a Bobby “Blue” Bland cover (“I Pity the Fool”), though afterward the emphasis was very much on his original compositions.

Again with the exception of Pin Ups‑devoted solely to mid-‘60s British rock classics—his choice of covers over these two decades was, like much of his career in general, enigmatic, unpredictable, and quirky. There were (even not counting Pin Ups) covers of some famous songs by the most famous artists. There were obscure songs by obscure artists. There were songs that hadn’t even been recorded by anyone else. There were non-rock numbers. There was a ‘50s rock’n’roll classic, a Brecht-Weill classic, English rewrites of Jacques Brel songs, and a movie theme. On unreleased outtakes, BBC broadcasts, and a filmed live concert, he managed to fit in covers of two songs by one of his biggest influences, the Velvet Underground.

In my view, however—unlike the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, both of whom he covered, and not on B-sides or bootlegs, but on two very popular LPs—Bowie wasn’t such a good cover artist. Take those Beatles and Rolling Stones songs—“Across the Universe” on Young Americans, and “Let’s Spend the Night Together” on Aladdin Sane. They don’t add particularly interesting twists to, and are in fact quite inferior to, the originals. His interpretations of “White Light/White Heat” (on the BBC in 1972 and in the film of his July 3, 1973 “retirement” concert, Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture) and “I’m Waiting for the Man” (on the BBC in 1972, and back in 1967 as an outtake backed by the Riot Squad) are appropriate sort of tributes to his admiration for Lou Reed. But they’re pretty routine and average as musical performances.

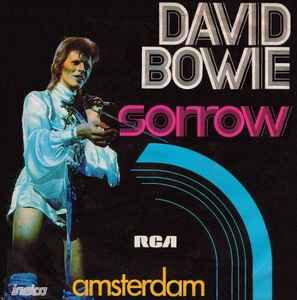

Although some of the public disagreed—the album did make #1 in the UK and do okay in the US—I’d say the same of Pin Ups as a whole. While I might find the LP unnecessary, I acknowledge something it did do was bring attention to a few songs (and groups) that were hits in the UK, but not in the US. Those include the Merseys’ “Sorrow,” a #3 hit in Bowie’s remake in the UK (and actually first done by the McCoys, though the Merseys had the big UK hit with a 1966 cover); “Rosalyn” and “Don’t Bring Me Down” by the Pretty Things, the best British ‘60s band not to make it in the US; and the Mojos’ “Everything’s Alright,” the last big mid-‘60s rock hit (again, only in the UK) by a Liverpool group new to the hit parade. Presumably publishing royalties were a help to some of the writers of these songs, particularly Syd Barrett, who had been out of the music business for a few years and was well into his downward mental spiral by the time Bowie put Pink Floyd’s “See Emily Play” on Pin Ups.

Most other Bowie covers don’t grab me either. These include quaint American singer-songwriter Biff Rose’s “Fill My Heart” (on Hunky Dory; he also did Rose’s “Buzz the Fuzz” in 1970 on the BBC); Chuck Berry’s “Around and Around,” considered for Ziggy Stardust but ultimately used as a B-side, and less interesting than the Rolling Stones’ dynamic 1964 cover of the same song; and, perhaps least predictably of all, the 1957 movie theme (and a hit for Johnny Mathis) “Wild Is the Wind,” done better by the legend who did the version that inspired Bowie’s, Nina Simone. There’s also his live cover of the ‘60s soul hit “Knock on Wood,” and his weird version of “Foot Stomping” (a 1961 early soul-rock hit by the Flares) on the Dick Cavett Show in 1974, which he did in concert as part of a medley with the popular standard “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate.” And there was his take on Brecht-Weill’s “Alabama Song” on a 1980 single, which isn’t nearly as memorable as the Doors’ version on their 1967 debut album.

Bowie also did a few covers that weren’t officially released until quite a few years later. Continuing the thread of his hard-to-pin-down cover tastes, he did versions of Bruce Springsteen’s “It’s So Hard to Be a Saint in the City” and “Growin’ Up” before Springsteen was a superstar, though Bowie’s variations are neither suited to his style or in the same league as the Springsteen originals. And there were songs he did live in the late 1960s as part of a duo (with John Hutchinson on backup vocals and second guitar) that never made it to circulating tape, like Carole King and Gerry Goffin’s “Goin’ Back” (recorded in the late ‘60s by the Byrds and Dusty Springfield) and, most unlikely of all, “The Prince’s Panties,” from the 1968 album Phonograph Record by Mason Williams of “Classical Gas” fame.

If you put together a mix tape of the original versions of the songs on Pin Ups, it would make total stylistic sense and sound great. If you put together a mix tape of everything else Bowie covered, it would sound kind of crazy, or at least like a mix tape put together by polling a dozen listeners, not just one. I’ve made my opinion known that I don’t think he was a great cover artist. But did he do any good covers (or at least ones I like)?

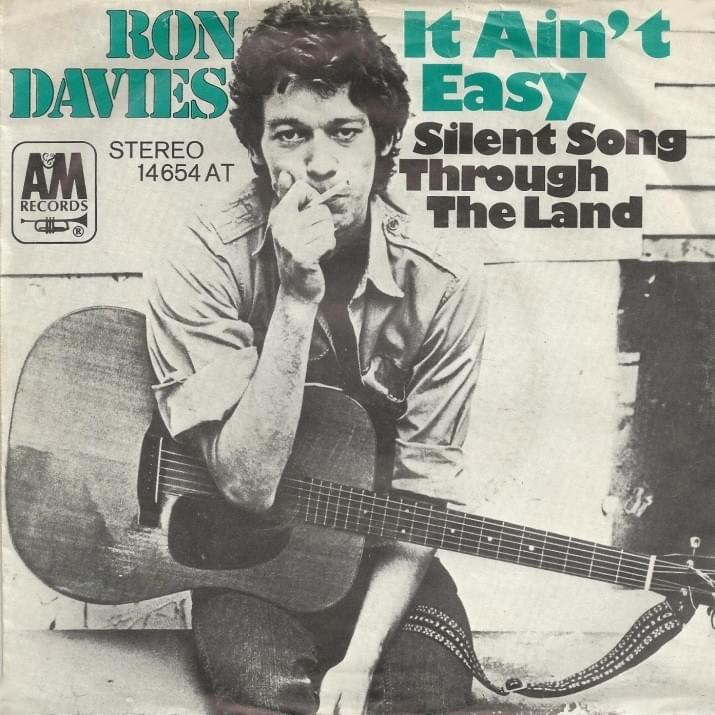

Yes. “It Ain’t Easy” somehow got onto the otherwise all-original Ziggy Stardust, credited to “Davies.” I admit when I first came across it, I assumed it was by Ray Davies. At least one other friend with a very deep record collection did too. But I’m not as familiar with the post-‘60s Kinks as the ‘60s Kinks; otherwise I would have known the Kinks didn’t have a song of that title. It’s actually by obscure American singer-songwriter Ron Davies, and appeared on his equally obscure 1970 LP Silent Song Through the Land. Bowie never made as much of his record collection as someone like Frank Zappa did, but obviously he was open to a lot of sounds to even become aware of people like Davies and Biff Rose, which must have been yet harder to do in the UK than the US (which Bowie didn’t visit until 1971).

Not everyone likes “It Ain’t Easy.” In his fine book The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s (which goes through every song he recorded through 1980), for instance, Peter Doggett writes that Bowie “doomed his performance by assuming a strangulated vocal tone that was, presumably, meant to sound both southern and intense, without achieving either aim.” I wouldn’t rank it as a highlight of Ziggy Stardust, but it fits in okay, and has a very catchy chorus—one reason I thought it might have been written by Ray Davies. There’s also a decent BBC version (from June 1971, predating Ziggy’s 1972 release by quite a bit) on Bowie at the Beeb, if you want something a bit different.

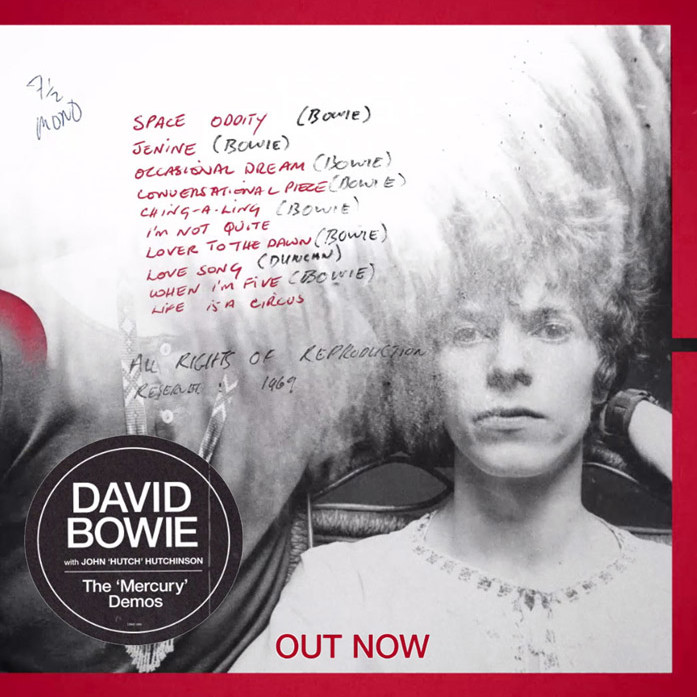

Far less widely heard than “It Ain’t Easy” are a couple covers on the unplugged demos Bowie and Hutchinson did for Mercury Records around spring 1969. After circulating for bootlegs for years, they were finally officially released a few years ago, most notably as part of the box set of late-‘60s recordings titled Conversation Piece. The Mercury demos are all well worth hearing in any case, and if more for early Bowie originals than the two covers, those two songs are performed well.

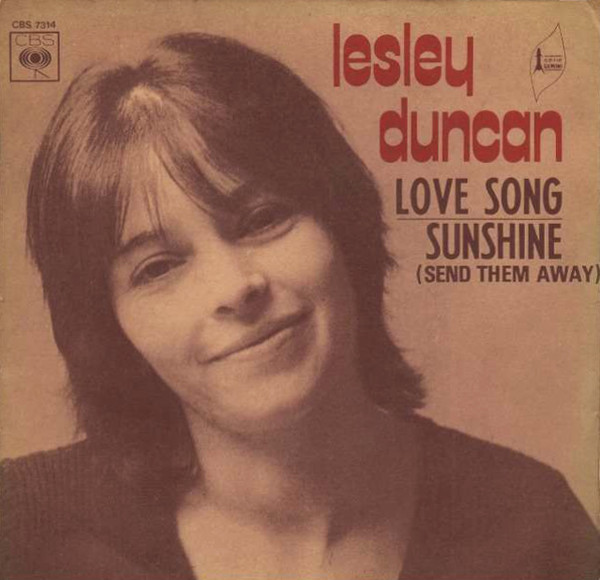

One is somewhat well known, but not by Bowie. That’s “Love Song,” written by British singer-songwriter Lesley Duncan, who Bowie referred to as being an on-off girlfriend who wouldn’t stop playing Scott Walker records. “Love Song” is her most well known composition, but not because of her own version (issued on a 1969 single). It’s far more familiar—indeed, for almost all of the public, only familiar—as part of Elton John’s 1970 hit album Tumbleweed Connection. Bowie and Hutchinson do a very nice acoustic version, harmonizing on the chorus. It might not be appropriate to call this a Bowie recording, since Hutchinson takes the lead vocal—the only one he sang on the tracks the pair cut together.

The other Mercury demo Bowie didn’t write was about the most obscure cover he ever did—which, considering how obscure some of the others were, is really saying something. “Life Is a Circus” somehow came his way from the British group Djinn, who didn’t even put out any records. It was written by Roger Bunn—not a household name, but known to some as a very early member of Roxy Music, though he was gone by the time they started making records. (He also had a 1970 solo album, but the song isn’t even on there.) “Life Is a Circus” is a very nice haunting, minor-keyed folk tune, again with affecting Bowie-Hutchinson harmonies, perhaps showing some of the Simon and Garfunkel sound Bowie’s sometimes been reported to have briefly aspired to at this point.

There was one major singer-songwriter who Bowie interpreted very well, though he might not be quite as well known to rock audiences as the likes of Springsteen and the Stones. That was Belgian Jacques Brel, who wrote songs with a European theatrical flair that fell outside of rock. His songs became well known to English-speaking audiences when American songwriter Mort Shuman (who’d penned quite a few early rock hits with Doc Pomus) translated some of Brel’s French originals into English. One of Bowie’s key early influences, Scott Walker, did quite a few Brel songs, including a couple Bowie performed in the early 1970s, “Amsterdam” and “My Death.”

“Amsterdam” made it onto a 1973 Bowie B-side, and a 1970 BBC version is on Bowie at the Beeb. He also did “My Death” onstage in the Ziggy era, and live versions are on both Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture and Live Santa Monica ’72. Bowie does both songs with forceful, dramatic confidence, and it’s easy to hear how such Brel tunes might have influenced some of his more overtly theatrical compositions of the time, like “Time.” Doing a whole LP of Brel songs in 1973 might have made for a better album than Pin Ups, if definitely a less commercial one.

2. The missing broadcasts. Considering he only had one hit in the 1960s, and that one (“Space Oddity”) not until late 1969, there are a lot of Bowie recordings available from that decade. The same can’t be said of video footage. In fact, apart from a brief gimmicky TV interview from late 1964 where he talks about a (presumably short-lived) society he and his band the Manish Boys have formed for long-haired men, there’s nothing music-related on film of Bowie predating 1969.

You could also count a little seen 1968 short film in which he had a silent acting sole (The Image), and super brief appearances in a late-‘60s feature movie (The Virgin Soldiers) and ice cream commercial, but those had no links to his musical career. If then-manager Kenneth Pitt hadn’t arranged for a half-hour promo film of sorts to be made around Bowie in 1969, Love You Till Tuesday, there would be dramatically less pre-1970 footage at all. That film wasn’t very good or successful in getting Bowie the attention Pitt intended, but its survival at least ensures he’s on screen miming to a few of his early songs (sometimes with John Hutchinson and then-girlfriend Hermione Farthingale), including an early version of “Space Oddity.”

Yet Bowie did sing with early bands he fronted on TV, and more than once, in the mid-1960s. As dismal as sales of his 1964 debut single “Liza Jane” were, he managed to perform them with the King Bees on Ready Steady Go—the top British pop music program of the mid-1960s, and indeed one of the best such programs of any time—as well as the lesser known Beat Room. He also did his fourth single, “Can’t Help Thinking About Me,” in March 1966 with the Buzz on Ready Steady Go, and his second single, “I Pity the Fool,” in March 1965 on Gadzooks! It’s All Happening.

These weren’t even the best of the half dozen singles he did before signing with Deram for an album and a few 45s in late 1966. But it would still be interesting to see him at such a young stage. Sadly, many British TV programs from this era—in a cost-saving move unimaginable considering how much they could have paid the initial cost back in the future, financially and culturally—were erased so the tape could be used again.

That’s even true of Ready Steady Go. Some episodes (particularly ones including groups already recognized to have huge commercial and historical value, like the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and the Who) survive. Most of them don’t. Bowie didn’t have a hit record then, and he was probably never considered for preservation.

There were also 1967-1969 performances of material from his Deram sides, including “Love You Till Tuesday,” “Did You Ever Have a Dream,” and “Please Mr. Gravedigger,” on Dutch and German TV that probably don’t survive. Frustratingly, a live color clip of him doing “The Supermen” live with the Hype is not only very short, but partially overlaid with some narration from Tony Visconti. Could there be more from the Hype filmed on this occasion, or at least more of “The Supermen”?

Of possibly more interest—especially because some or all of the few missing mid-‘60s clips would have been mimed, not live, and not even to the best of Bowie’s pre-Deram songs— some other unreleased recordings from the time are known to exist. That includes some more demos with producer Shel Talmy than the five that came out on the Early On (1964-1966) compilation and the unreleased 35-minute song cycle about a suicide party (sic) by a character named Ernie Johnson that was recorded in spring 1968. A fragment of one of the Talmy demos, “I Want Your Love” (not a Bowie composition, and done by the Pretty Things on their second album), has circulated online; the Ernie Johnson song cycle is detailed at length in Peter Doggett’s The Man Who Sold the World book.

3. “The London Boys.” Buried on the non-LP B-side of a single from late 1966 that sold barely anything, “The London Boys” was aptly described by Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray in Bowie: An Illustrated Record as “probably the most moving and pertinent work that Bowie produced prior to prior to ‘Space Oddity.’” It hasn’t been hard to get since first getting reissued in 1970, but still isn’t extremely widely known, though in fairness that can be said of everything Bowie did before “Space Oddity.”

Bowie was famously, and in the eyes of some notoriously, cagey about revealing much of himself in his songs, or at least in discussing exactly how much in his songs was autobiographical. It seems likely, however, that at least part of “The London Boys” comes from personal experience. Unlike almost any other mid-’60s British pop record, it documents the morning-after comedown side of the mod experience, not the exhilarating amphetamined highs. While the oft-flatulent orchestration of Bowie’s Deram sides usually worked against him, here it—maybe inadvertently—complements the lyrics of a struggling mod. The sad blurry horns soundtrack what sounds like the weary aftermath of a night of partying and pilling.

“The London Boys” might have been too much of a downer to stand a chance of charting in 1966. More mysterious, however, is its failure to get pushed more prominently by his record labels. He actually first recorded it (in a still non-circulating or lost version) in late 1965 when he was still being produced by Tony Hatch (of Petula Clark “Downtown” fame) at Pye Records.

Somehow it was passed over for release at the time, Bowie giving the explanation, “It goes down very well in the stage act, and lots of fans said I should have released it. But [Pye producer] Tony [Hatch] and I thought the words were a bit strong…we didn’t think the lyrics were quite up many people’s street.” Perhaps they and Pye Records also thought the direct reference to taking pills would have blocked possible airplay.

Presumably “Can’t Help Thinking About Me,” Bowie’s first Pye single, was deemed more commercial. It was, but not extremely so, peaking at a mere #36 in Melody Maker (and not entering any other UK charts). It’s been reported that it was suspected it was bought into the Melody Maker charts with some payola. Bowie’s next two (and final) Pye singles were yet slighter. Wasn’t it worth taking a chance on “The London Boys,” even as a B-side? Which of course Deram did in late 1966, but as the B-side of the vastly inferior “Rubber Band,” one of Bowie’s most blatant (and embarrassing) sub-Anthony Newley vaudevillian pop efforts.

4. The “real” David Bowie (or David Jones). Bowie’s often been characterized by, and lauded for, unpredictably changing styles, images, and even to some degree his personality, musical and public. This in turn has frustrated some critics who feel like it’s hard to figure out who the “real” Bowie is, or even suspect there isn’t a “real” Bowie, that he’s superficial gloss. At least in his music, which is often about other characters, or assuming a character, most famously Ziggy Stardust and then in his “Thin White Duke” phase.

There have been some apparent autobiographical elements in his songs, however. As noted in the above entry, “The London Boys” seems likely rooted in some personal experience as a mod in his late teens struggling to get a foothold in the music business. Even “Can’t Help Thinking About Me,” as relatively slight as it is, seems to have some reflective doubt that comes out of adolescent confusion and at least one love affair. Years later on Hunky Dory, “The Bewlay Brothers” seemed, if only in its title, to refer to him and his half-brother Terry, who spent much of his life struggling with mental illness.

I’ve written this a few times before, but it seems to me that his brief “Simon and Garfunkel” phase as part of a duo with John Hutchinson might be the closest he came to singing as himself, not as a character or someone trying to elude being pigeonholed. The ten-song acoustic Mercury Records demo he did with Hutchinson in early 1969 seems like Bowie at his most sincerely personal, in part because the music (and not just the lyrics) is so unadorned and direct.

“Letter to Hermione” (titled “I’m Not Quite” on the demos) doesn’t even make any bones about who it’s addressed to, or change the name of the girlfriend he’d just broken up with (also a bandmate of his and Hutchinson’s in the short lived trio Feathers), Hermione Farthingale. “An Occasional Dream” also seems very specifically about his and Farthingale’s relationship, and though “Janine” was actually about the girlfriend of his good friend George Underwood, it has the knowing detail of something from real life. “Conversation Piece” is more abstract, but also seems to have a thoughtful and at times joyful spirit not filtered by self-conscious aspiration toward making oblique art. On the other hand, the most striking song from the demos, “Space Oddity,” is very much about an invented character and situation, and very effectively so.

Here’s what Hutchinson himself told me in a 2014 interview: “Yes, I would say, in those days he was just himself. David Jones and David Bowie were the same person. Whereas when Ziggy happened, it got a lot more complicated, and he was singing as somebody else. He was third person or removed, or whatever it is. He’d written songs for this alter ego or other person to sing. He could sing whatever he wanted them to, he could write whatever he wanted them to say, and maybe it wasn’t sincerity from him. But I don’t think he had a lot of that going anyway. I think it was all performance.”

“When you say you ‘don’t think he had a lot of that going,’ are you referring to the singer-songwriter approach?” I asked.

“Yeah, I don’t think he had very much of that going at all. He was playing a part, and writing his stories, as the character that he’d created. So I’m agreeing with you, I suppose, that he was much more honest during those ‘Space Oddity’ days, if you like, the acoustic days. I think he was totally honest then, and it’s just that the way that he wrote and performed changed when he realized he could invent a persona. You know, David Bowie was just a stage name. But Ziggy Stardust was a character.

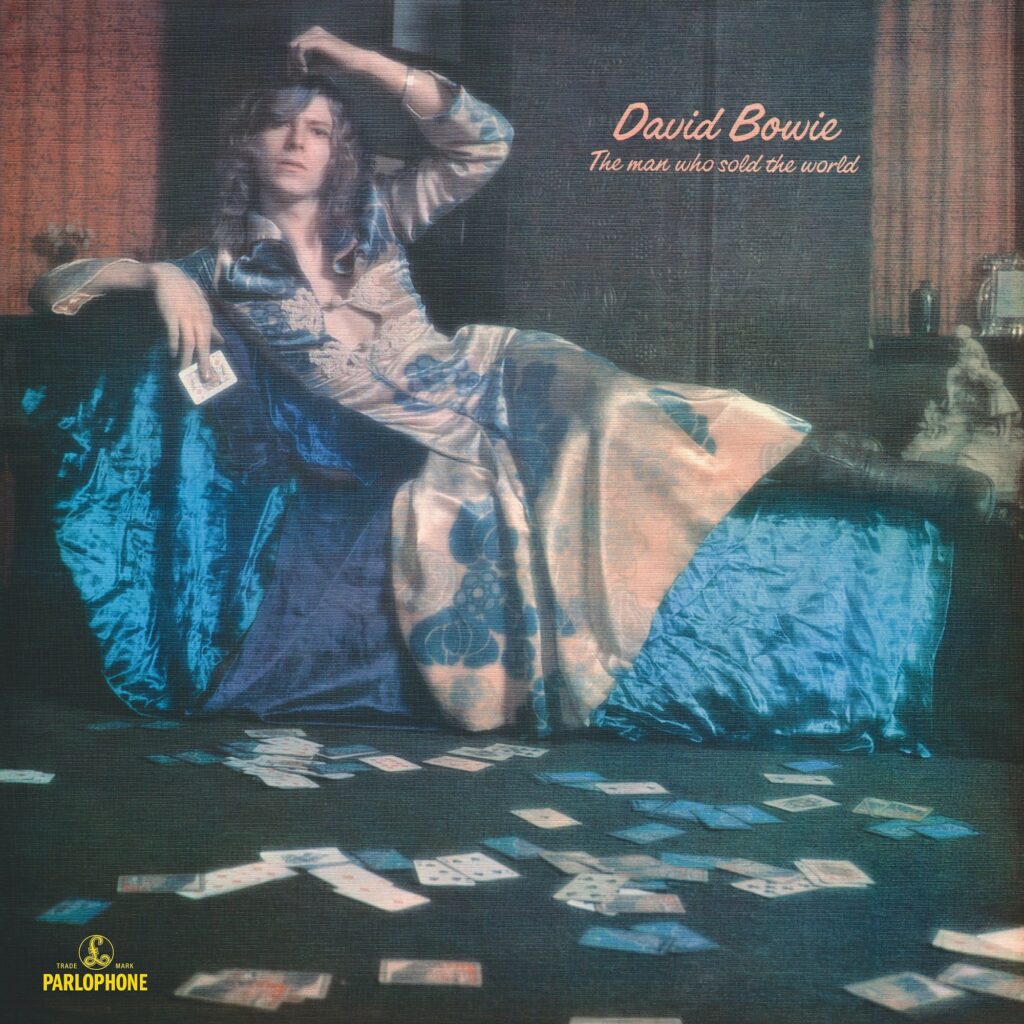

5. ”The odd release history and reception of The Man Who Sold the World. Bowie’s third album, 1970’s The Man Who Sold the World, is both his most underrated and the first where he really found a strong, consistent, and distinctive sound and approach with top-notch material throughout the record. It didn’t sell very much, however, despite attracting some rave reviews even at the time. Why?

A few reasons can be speculated. There wasn’t a song as obviously catchy and hit material as “Space Oddity,” or for that matter, “Changes” from his next album, Hunky Dory. “Changes” was only a low-charting single in the US when it was released, but became something of a hit by virtue of heavy rotation on FM radio over the years. Nothing from The Man Who Sold the World got such airplay, to my knowledge, at least in the commercial sector.

Bowie also performed surprisingly little in the year or so after its release. Even when he visited the US for the first time in early 1971, he was limited to doing promotional interviews and activities in a few cities, and didn’t do any official concerts. He’d tour heavily for a year and a half or so soon in his Ziggy period, but that might not have helped boost back catalog sales of The Man Who Sold the World too much, since he featured little of its material in his Ziggy-era concerts.

A more subtle factor was its strange release history. The album came out near the end of 1970 in the US, where “Space Oddity” hadn’t been a hit, and Bowie was still nearly unknown, despite starting to build an underground following. In his native UK, where “Space Oddity” had been a hit, the record didn’t come out until April 1971, nearly six months later. How did that happen?

The answer isn’t entirely clear even in the best Bowie biographies, but it might have been due to him—unusually for a British artist at the time—being signed directly to an American label (Mercury), not a UK one. Mercury, for whatever reason, might have felt that the album, or Bowie himself, stood a better chance of selling well in the US than in his homeland.

Famously or infamously, there was also controversy over the cover. The US, and thus first, one had an enigmatic cartoon with a caricature of John Wayne and a wordless speech bubble. The subsequent, yet more controversial, UK one pictured Bowie in a full-length dress—outrageous for a male recording artist in 1971. Yet if Mercury was hoping the US was where Bowie would be break, they were disappointed. According to Nicholas Pegg’s The Complete David Bowie, it sold just 1395 copies in the US through June 1971, about half a year after it came out.

Despite that low sales tally, there are indications that where the album was heard in the US early on, it picked up some very avid fans. During that visit, he was able to do interviews on popular FM radio stations in Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Here’s an anecdotal testimony to early Bowie adapters: as a college student in the early 1980s, I was a DJ on a Philadelphia-area college radio station with a big vinyl LP library. It still had the original 1970 edition of the album. The back cover was itself nearly covered with enthusiastic handwritten rave comments from station DJs—not over the past dozen years, but at the time it was released. Very few albums in the station’s collection (which held tens of thousands of LPs) were blanketed with such handwritten praise, even some very famous hit and cult ones.

Too, the record attracted a rave review in Cashbox, the biggest American music business magazine besides Billboard. Wrote an anonymous reviewer in the publication’s December 26, 1970 edition, “David is a huge talent. His writing is unique in all of music and part of his recognition problem stems from the fact that he is way ahead of mainstream rock… If you feel you might like to get in on someone now who others will be shouting about next year, pick this up…every track trembles with excitement and musical expertise.”

Cashbox (and Billboard) usually reviewed albums with bland enthusiasm. Although only one paragraph in length, this review has a lot more fervor than was customary for a Cashbox reviewer. Here’s guessing a young staffer who got hip to Bowie and the album way ahead of most Americans made a determined effort to slip in a much more passionate recommendation than usual, maybe even taking advantage of a short-staffed Christmas-period week or two to get it into print. Less surprisingly, the album was also reviewed well in Rolling Stone, where it was hailed as “uniformly excellent” and “an experience that is as intriguing as it is chilling.”

The Man Who Sold the World eventually had its day, if not as bright as Ziggy Stardust or for that matter Hunky Dory. After Bowie broke as a star, it made #26 in the UK and #106 in the US—not too high, but a lot higher than missing the charts entirely, as it had first time around. But given how well it was received by at least some US press and radio back in early 1970, is it possible Mercury under-reported its sales through June 1971? It certainly seems like Mercury under-promoted the record worldwide, likely leading in part to Bowie signing with a different label, RCA, later in 1971, who threw much more weight behind publicizing the singer and getting his music heard.

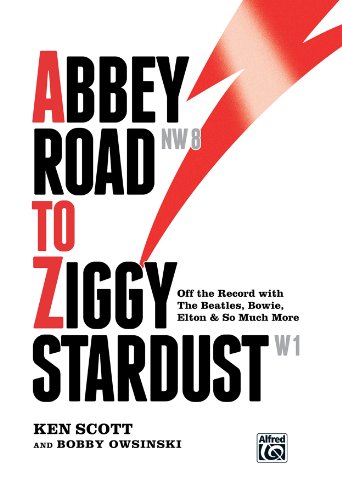

6. Ken Scott. Of the producers Bowie worked with, Ken Scott hasn’t gotten ignored by biographers. But he hasn’t gotten nearly as much attention as the one Bowie worked with the most and most closely, Tony Visconti. There are good reasons for that. Visconti worked on quite a few Bowie records, from 1968 until Bowie’s death nearly half a century later. Unlike Scott, he played instruments on some Bowie records, most notably bass on The Man Who Sold the World. He was also generally a much closer friend to Bowie than Scott was, in part because Scott’s time with Bowie was relatively short.

But his time with Bowie was enormously significant. He co-produced (with Bowie) the singer’s most important albums in the journey from cultdom to stardom: Hunky Dory, Ziggy Stardust, and Aladdin Sane. He also co-produced Pin Ups, which wasn’t nearly as notable, but was a big seller. It’s likely Scott wouldn’t have replaced Visconti for these years if Visconti wasn’t wary of Bowie’s manager of the time, Tony Defries, with whom the producing Tony didn’t get along. Yet it’s hard to imagine Visconti, or anyone, doing a better job than Scott did.

Scott’s side of the story is well told in his book Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust (co-written with Bobby Owsinski), which also discusses his time engineering on late-‘60s Beatles sessions and producing other artists. Here are two of my favorite of Scott’s observations. As he admits in the section on Bowie, he initially viewed Hunky Dory as a chance to make the move from engineering to production in a low-key way with a low-profile artist where any failure on his part wouldn’t be noticed. He quickly realized that wouldn’t be the case—as he writes, “As we were going through the material it suddenly hit me. ‘Hang on, this guy is really fucking good. He could be a lot bigger than I expected and this album might actually be something that a lot of people will listen to. Crap.’ Here it was again. Trial by fire.”

Scott also hails Bowie’s efficiency in the studio, noting that “95% of his vocals on Ziggy and every other album I recorded with him were done in a single take.” That might not sound like such a big deal, but even half a century ago, it was hardly a given that anyone did their vocals in one take, especially as recording generally got more sophisticated and prolonged.

7. Bowie as benefactor. Bowie isn’t usually noted as an especially generous celebrity. Indeed, often biographers have portrayed him as pretty self-interested at various points in his career. But in the early 1970s, before he was an established superstar, he helped a few people out who really needed it, at a time when he was barely past the point of really needing it himself. At the time, it wouldn’t have seemed to many people that there was much in it for Bowie to be producing and writing for the people he did.

Yet he did help out a few major acts. He likely not only kept Mott the Hoople from breaking up by producing their All the Young Dudes album. He also wrote and produced their biggest hit, “All the Young Dudes,” at a time when he could have used a hit himself—his second big UK hit, “Starman,” wasn’t even in the charts yet (though it would enter them very soon). A little later in mid-1972, he co-produced (with Mick Ronson) Lou Reed’s Transformer, helping give one of his prime heroes his first hit LP and (with “Walk on the Wild Side”) biggest hit single. By many accounts, Reed wasn’t the easiest guy to get along with or work with, which makes Bowie’s advocacy all the more admirable.

Speaking of guys who weren’t always easy to work with, Bowie took a chance with Iggy Pop and the Stooges by helping him get to be part of the MainMan organization then looking after Bowie’s affairs. He also helped mix the Stooges’ 1973 album Raw Power, though accounts vary as to whether that was necessary or an improvement. Four years later, well after he’d cut his ties with MainMan, Bowie continued to help a down-and-out Iggy by producing, and co-writing much of the material on, Pop’s two 1977 solo albums. He even toured with Pop’s band at the time on keyboards, again when there seemed little for him to materially gain from the association, though he would get payback of a sort when he made one of the songs from the Pop 1977 albums, “China Girl,” a big hit in 1983.

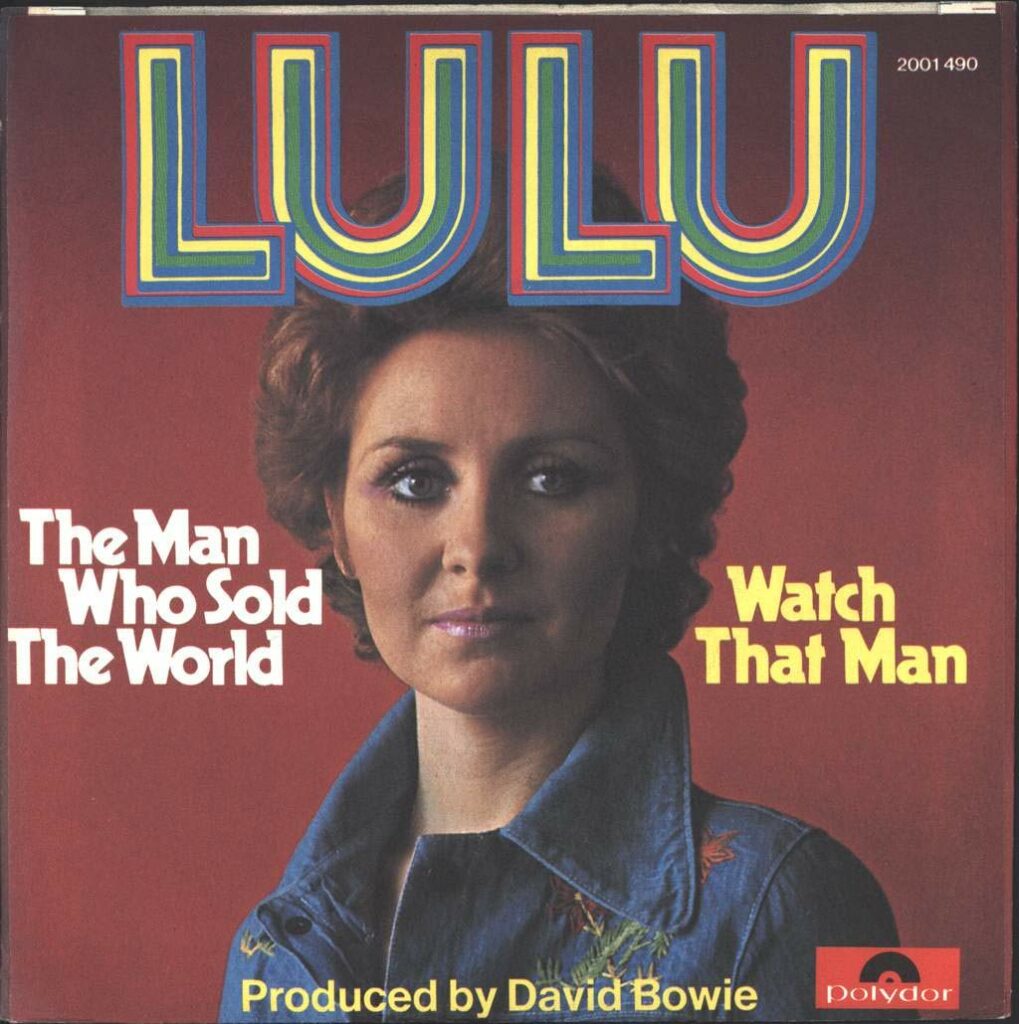

Bowie also helped Dana Gillespie, a girlfriend of his back in the mid-1960s, get on the MainMan roster and did a little production for her, most notably on a cover of “Andy Warhol.” And he, most unexpectedly, produced a hit single for Lulu in 1974, “The Man Who Sold the World”/ “Watch That Man,” at a time she’d been off the charts for four years.

It could be argued that Bowie getting Mott, Pop, and Gillespie with MainMan was a mixed blessing, given manager Tony Defries’s mixed reputation and Bowie’s own break with Defries in 1974. In her recent memoir, Gillespie writes that litigation with MainMan meant she was unable to record for a few years. Nonetheless, her assessment of Defries is generous; she notes she never would have gotten to experience the highs of the glam era without him, and wouldn’t give up those years for anything.

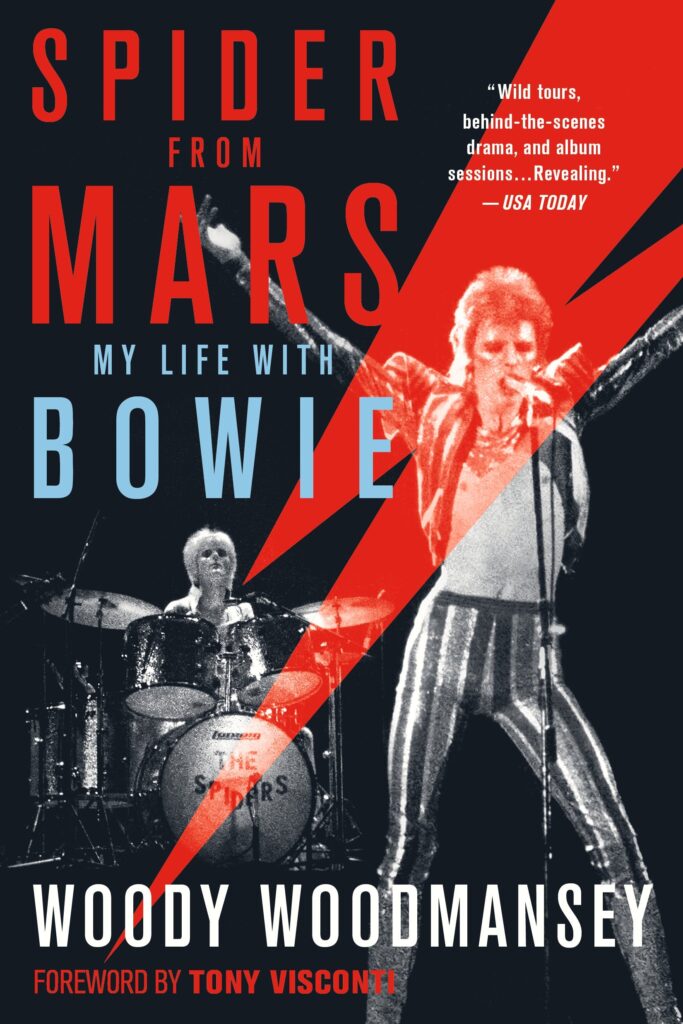

8. The breakup of the Spiders from Mars. The Spiders from Mars are by far Bowie’s famous backup musicians, yet the full trio of Spiders only worked with him for about a couple years. Their famous “retirement” at the July 3, 1973 London concert filmed for Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture pulled the plug on them unexpectedly. It’s sometimes forgotten that two of the Spiders did play with Bowie a bit longer, with guitarist Mick Ronson and bassist Trevor Bolder playing on Pin Ups and at the 1980 Floor Show TV special filmed in London’s Marquee in late 1973, with Aynsley Dunbar replacing Woody Woodmansey on drums. Still, the Spiders were out of a job much sooner than they seem to have expected.

The reasons for this, as they are for a few other things discussed in this post, aren’t entirely clear. There seems to be a combination of factors: Bowie’s genuine desire to move on to a different style and different musicians; increased discontent from the Spiders at their relatively low wages, especially after they learned new keyboardist Mike Garson would be making a lot more; and a wishful-thinking plan/hope by Tony Defries that Mick Ronson could be a solo star (Ronson wasn’t), and growing tension between the Spiders and Defries.

Back to my 2014 interview with John Hutchinson for another viewpoint on why the Spiders finished with Bowie’s premature “retirement”: “It was just that they knew they weren’t selling tickets, and the money supply was gonna be cut off from RCA, basically.” Hutchinson wasn’t a Spider, but he played with them and Bowie on tour in 1973 as an extra 12-string guitarist. Bowie’s onstage retirement announcement was a surprise to him, as it was to Woodmansey and Bolder. Hutchinson was out of a job immediately, driving back to the north of England without a job or a place to live, owning only his car, guitar, and a suitcase.

“It looked to me like he was ready to take a break,” Hutchinson added. “I mean, I do remember on the UK tour, that everybody was getting pretty bored with it all. The same stuff had been performed every night pretty much in the same way. He must have been ready for a break in a financial sense, business sense, emotional, physical. I guess that’s why he retired. All those things. Rather than putting his band on hold. I think the Spiders were sort of likely to be sort of folded up anyway, that’s the way it was looking. That what he and Mick really wanted was a nine-piece band.”

Here’s a viewpoint of mine that I don’t see come up too often. While a split might have been inevitable, it’s unfortunate Bowie didn’t stay with the Spiders from Mars for at least one more studio album of original material. It seems like they could have handled Diamond Dogs, or at least much of Diamond Dogs. To draw a rough analogy, it’s kind of like how I feel Janis Joplin should have stayed with Big Brother and the Holding Company for at least one more album before working with other bands.

9. Bowie as actor. Bowie’s acting debut in a feature length film, 1976’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, was impressive. The film itself was very impressive. However, there might be some weight to some critics’ observation that Bowie was playing a character not unlike himself. Or, at least, not unlike his mid-‘70s image, down to the wardrobe and dyed red hair. Mick Jagger got some similar criticism for his starring role in Performance, a late-‘60s cult film co-directed by Nicolas Roeg, the sole director of The Man Who Fell to Earth.

I haven’t seen all of Bowie’s subsequent films, but I don’t think he ever did as well as The Man Who Fell to Earth as an actor, or ever got another movie or role as good. These include parts in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, Absolute Beginners, The Hunger, and The Last Temptation of Christ. Some parts were substantial, some were rather minor supporting roles or even brief. The Linguini Incident was embarrassing in all respects.

It’s a little puzzling to me that he never got another starring film role in which he was as much the star as in The Man Who Fell to Earth. In part that’s because in 1980, he received considerable critical acclaim for his starring role in a Broadway production of The Elephant Man. As some biographers have noted, this was especially impressive given that theater critics would not be nearly as likely to be impressed by his rock star credentials as some film critics and many moviegoers, or likely to cut him slack because acting wasn’t his principal profession.

He didn’t star in David Lynch’s film version of The Elephant Man, which was probably for the best. John Hurt did a spectacular job in that role, and it’s unknown whether Bowie was up to the demands of playing the elephant man in heavy makeup that would have made him unrecognizable (unlike in the Broadway production, where he wasn’t required to be made up in that way). Why didn’t he get another respectable starring role or two in the cinema? Maybe it was just down to not getting the right film/director/offer pitched to him.

And here are a couple notes about footnotes in his career:

1.“Young Americans” on The Dick Cavett Show. When Bowie performed on The Dick Cavett Show in November 1974, he previewed the title track (and hit single) off his upcoming Young Americans album. Near the end of the studio recording, there’s a point where the instruments drop off and he slows down the lyric, singing “break down and cry” in about the highest voice he mustered. On The Dick Cavett Show, he doesn’t even try to hit those high notes, singing much lower ones.

His Dick Cavett Show appearance is usually discussed in terms of how strange he looked and acted, sniffling during the interview and looking so gaunt it seemed like he weighed less than a hundred pounds. That’s led to speculation that he was high on cocaine. Whether or not that’s so, or to what extent it’s so, one wonders whether less-than-optimal condition affected his ability to hit those high notes, or whether he thought he couldn’t in his condition.

One more note about this appearance: he sang “Young Americans” on national TV for an episode broadcast in early December 1974 (I’ve seen both the dates of December 4 and December 5 reported). That’s a good two and a half months before “Young Americans” was first released (on a single, a little before the Young Americans album). These days, such advance exposure of a new song/single would likely not just be rare, but considered by many in the business to be downright damaging. It would also be considered unwise, or even foolish, to spend precious network time presenting a song that was unavailable for purchase. But those were the days when industry policing of such things was far less restrictive, and we were all the better for it.

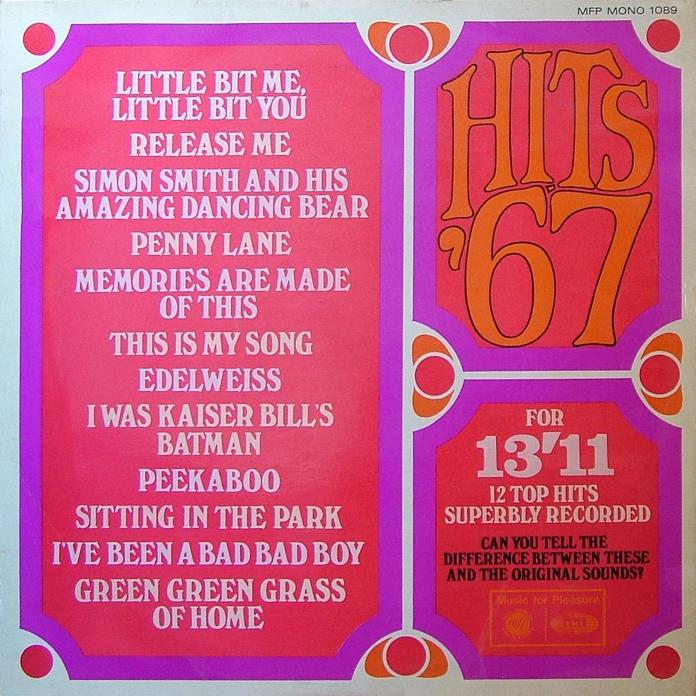

2. Is that David Bowie on “Penny Lane”? Not on the hit Beatles recording, of course, but on a soundalike version that came out on the UK budget LP Hits of ’67, devoted to recreating the sounds of big hits at a much lower price. And at a much lower quality – some of those soundalikes didn’t sound exactly like their prototypes. The version of “Penny Lane” has an anonymous singer who sounds so much like Bowie that when I played it many years ago for someone, she instantly said, “That’s Bowie.” And though at least one writer I’ve read dismissed such a guess as ridiculous, really more people than not think it certainly sounds like Bowie, and enough to possibly be a young Bowie picking up a few pounds as a session singer. Other vocalists who’d later become well known picked up some money on soundalike budget discs, most famously Elton John, who did enough such sessions that there’s a whole CD of his soundalikes.

The ”Penny Lane”-Bowie rumor picked up steam when the track was officially issued on the 2001 CD compilation Hot Hits on 45, though it had already done the rounds on Bowie bootlegs for quite some time before that. In January 2013, however, Record Collector magazine clarified that it wasn’t Bowie, but in fact a session singer named Tony Steven. The uncanny similarity wasn’t, of course, Steven imitating a then-nearly-unknown Bowie, but more a matter of both of them being influenced by Anthony Newley.