The recent death of George Martin sparked some discussion—which has been ongoing since, without exaggerating, at least 1964—as to who deserves the title of Fifth Beatle. New York radio DJ Murray the K might have been facetiously self-promoting when he came up with the term to describe himself after attaching himself to their entourage on their first US visit, but many serious and casual fans like to debate the question. Who, to phrase it another way, was the most important figure in the Beatles career besides the Beatles themselves?

People often make jokes—which by now are quite tired—in their answers, citing such obviously silly choices as Ed Sullivan or Murray the K himself. Really, however, there are only two serious contenders for this title. One is Brian Epstein, their manager from late 1961 through his death in August 1967. The other is George Martin, the producer of virtually all of their studio recordings.

Epstein’s importance to the Beatles can’t be overestimated. He believed in and pushed them when no one else with his resources did; he did not interfere with their music; and, despite some questionable business decisions, was devoted to their artistic and personal interests. But when you come down to it, the most important thing about the Beatles was their music, and the most vital components of their musical legacy were their studio recordings. And their most vital collaborator on those recordings, by far, was George Martin. He never promoted himself as the Fifth Beatle, but if anyone should get the title, he deserves it.

Numerous recent obituaries have pointed out his contributions to the Beatles’ records, and entire books could be written about them. (As I noted in my post last year about rare rock books, Martin himself wrote one, Playback, which was a very expensive limited edition that now sells for hundreds of dollars, and which I haven’t read; his less extensive With a Little Help from My Friends, which focuses on his work on Sgt. Pepper, is readily and cheaply available.) Martin tributes rightly praise his sympathetic and skilled use of orchestration on their recordings from the mid-1960s onward; his ability to translate the Beatles’ more daring, sometimes wild, ideas into effective recordings; and the generally superb sonic quality of the band’s records, for which Abbey Road engineers and staff also deserve some credit. In this post, I’ll point out a few things which don’t get quite as much attention.

While it’s more fun to focus on the positives of what did happen in Beatles history than speculate on what might not have happened had things turned out differently, it’s truly scary to think of how wrong things could have gone if they hadn’t been produced by George Martin. Which would have happened had they passed their audition with Decca Records on January 1, 1962, when Pete Best was still their drummer. At the time, they were crestfallen at their failure to get a contract with Decca (or any of the other big UK labels).

As I’ve emphasized in classes I’ve taught about the Beatles and presentations I’ve given about them, at the time, the group felt like it was the worst break imaginable. In retrospect, I contend, it was the best break they ever got. One reason is that it gave John Lennon and Paul McCartney time to write better songs than the original material—meager in quantity (three compositions) and not nearly up to their 1963 recordings in quality—they played at the Decca audition. Another is that it gave them about half a year in which to consider whether they wanted to replace Pete Best with a better drummer who’d also fit in with them much better as a personality—which Ringo Starr did, perfectly, when he joined in August 1962. The biggest, however, is that if they’d signed with Decca, they wouldn’t have been produced by George Martin, the best imaginable producer for the Beatles.

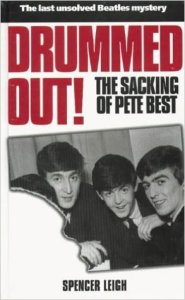

Imagine what would have come to pass if someone at Decca—perhaps Mike Smith, who conducted their audition for the label—had produced them instead. Smith himself had a frank and blunt assessment in Spencer Leigh’s book Drummed Out! The Sacking of Pete Best: “I don’t think I could have worked with them the way that George Martin did—I would have got involved in their bad parts and not encouraged the good ones.” As if to illustrate the point, he actually told the Beatles fan magazine The Beatles Book that Pete Best “was a better drummer than Ringo.”

More specifically, had the Beatles signed with Decca and been produced by Smith or someone else on the label’s staff, it’s quite possible that:

A) They would have been forced to record inappropriate pop material written by composers from the equivalent of the British Tin Pan Alley. George Martin, as is well documented, actually wanted them to do this by recording Mitch Murray’s “How Do You Do It” (later a hit for Gerry & the Pacemakers) for their first single. He swiftly realized (to his credit) that it wasn’t a good match for the Beatles, and that they should be allowed to record their own material.

B) Session musicians might have been used on the Beatles’ records, as they often were in early-‘60s rock records in the UK (and US). Note again that George Martin did this by engaging Andy White to drum on the Beatles’ first single. Again to his credit, he realized that Ringo should be drumming, as Starr did on the 45 version of “Love Me Do” and on the band’s records from late 1962 onward. My guess is that very few producers of that era would have had the wisdom and humility to let the band be as they were, instead of imposing songs (sometimes, uncoincidentally, written by the producers) and musicians on them against their will and against common sense.

C) The sound simply wouldn’t have been as good on the records, regardless of what songs they cut. They would have likely been of higher fidelity than the basic, if acceptably professional, sound of the fifteen songs on the Decca audition tape (which have long been bootlegged, and about half of were officially released on Anthology 1). But they almost certainly wouldn’t have been as good as what was recorded in EMI Studios at Abbey Road. As an even scarier thought, it’s possible the Beatles might have been augmented by inappropriate orchestration and chirpy background vocals by session singers, as much lame pre-Beatles British rock was.

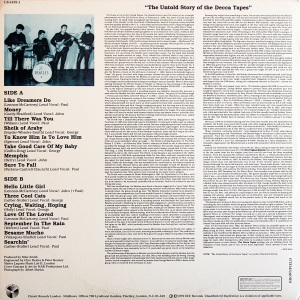

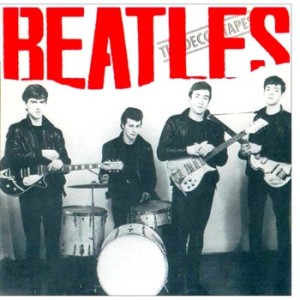

For another take on how a Decca deal might have turned out badly for the Beatles, read “Grid Leek”’s pseudonymous, lengthy essay “The Untold Story of the Decca Tapes,” which are small-print liner notes on the back of the 1979 bootleg LP The Decca Tapes (on Circuit Records). Leek writes the story as if ten songs from the Decca tapes actually came out on 1962 singles, with the other five added to this LP as “outtakes.” There are problems with its premise: had the Beatles signed to Decca, they would have made different recordings for release than the ones on their audition tape, and quite possibly cut different songs altogether. In Leek’s historical fiction of sorts, however, all five of the singles flop, with the Beatles only becoming successful after signing with EMI and releasing “Love Me Do” with Ringo on drums (as happened in real life).

The back cover of the first bootleg to feature all 15 songs from the Beatles’ Decca audition had fictional liner notes recapping what might have happened had the Beatles signed to Decca and released material on the label.

Who would have been a good producer for the Beatles, if George Martin hadn’t been their miraculous match? I’m not sure there was any other good producer for the Beatles in Britain at the time. London-based American expatriate Shel Talmy (who produced mid-‘60s hits for the Kinks and Who) might have done well or at least okay with them, but he hadn’t even moved to England at the time of the Decca audition. I had the chance to ask Talmy if he would have turned down the Beatles on the basis of their audition in early 1962, and though he had the benefit of lots of hindsight, he responded, “I don’t think I would have, because I’ve always been very song-oriented. Although they were not a wonderful band musically, the songs were outstanding, even then. And I’m sure I wouldn’t have turned them down.”

How about Andrew Loog Oldham, the Rolling Stones’ producer? He was really more of an image-making publicist and enabler of the Stones to sound like themselves on record than a creative force in the studio, without any of the musical training or extensive experience Martin brought to the job. Giorgio Gomelsky, who managed/co-produced the early Yardbirds (and unofficially managed the Stones at their very beginning), likewise lacked that musical/studio background, and though he had an appetite for daring experimentation, probably lacked the professional focus at which Martin excelled. Mickie Most proved with the best of his records with Donovan and the Animals that he could make great and innovative discs, but was really more of a guy with a good commercial ear than one who prioritized the best artistic results.

It comes down to this: George Martin was really the only guy in the whole of the British recording industry with good qualifications to produce the best British rock band. Just because he was the only guy, however, doesn’t mean he wasn’t a perfect guy for the Beatles.

Moving to what Martin actually did with the Beatles, one of his great contributions was encouraging them to focus on their original material, once he’d gotten over his initial brief resistance to using their compositions. I didn’t realize the full extent of this until reading the extended edition of the first volume of Mark Lewisohn’s mammoth Beatles biography, Tune In (which only covers the story until the end of 1962). John and Paul hadn’t even done much writing in the first couple years of the 1960s before getting back in gear in 1962, and Martin hadn’t been too impressed by “Love Me Do” or the other originals they presented to him at their first sessions. Lewisohn’s book also takes the view that had pressure from publishing interests not been at work, the Beatles’ first single might very well have been Mitch Murray’s “How Do You Do It” instead of a Lennon-McCartney original, which would likely have altered history much for the worse.

Yet the modest commercial success of “Love Me Do” and enthusiasm over the freshly penned “Please Please Me” apparently spurred Martin to give the go-ahead to a Beatles album with much of their original material at a meeting with the group in mid-November 1962, even before “Please Please Me” was recorded, let alone on its way to becoming chart-topping hit. This was key to transforming their relationship from one of a band operating under a nonplussed record company functionary to one collaborating with a supportive and valued artistic ally. As Lewisohn writes:

George Martin’s idea that the Beatles should make an LP was extraordinary; that he wanted it packed with (and perhaps full of) John and Paul’s songs is even more so, and there can be no better barometer of both his transformed attitude and interest in seeing where it would lead. This was the man whose reflection on being shown ‘Love Me Do,’ ‘P.S. I Love You’ and ‘Ask Me Why’ was, ‘I didn’t think the Beatles had any song of any worth – they gave me no evidence that they could write hit material.’ Since then, he’d heard ‘Please Please Me’ and ‘Tip of My Tongue’ (much preferring the former) and that was it…but, nonetheless, he’d changed his mind…this was a volte-face of immense proportions.

Again, my guess is that very few producers of that era would have had the wisdom and humility to backtrack on their strategy, in effect admitting they were wrong. But not only admitting they were wrong—to also take a new and more effective strategy with enthusiasm that likely fired up John and Paul to write more and better songs, now that they knew their producer had their back.

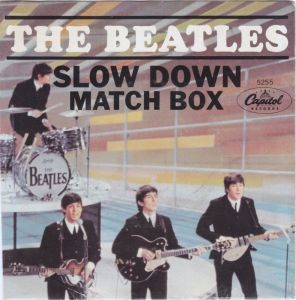

Another virtue of Martin’s that gets a little underplayed—though many more people are aware of it now than they were in the 1960s—is just how often he actually played on Beatles recordings. Most often he was on keyboards, and though he had fairly little experience producing rock’n’roll (and, I’m guessing, virtually none actually playing it), he was a hell of a piano player. On early songs like “Slow Down” and “Rock and Roll Music,” he really is a fifth member of the band, playing piano with a furious bluesy boogie-woogie energy that even Nicky Hopkins (the top British session keyboardist of the 1960s) might have been hard-pressed to match.

“Slow Down” was released on a US single in 1964, and was (with its flipside, “Matchbox,” on which Martin also plays piano) a small American hit.

If Martin helped bring out qualities in the Beatles that were instrumental in them breaking out of pure rock into orchestrated arrangements influenced by classical, music hall, jazz, the avant-garde, and other styles, the Beatles seemed to bring out the closet rock’n’roller in George, at least in their pre-1966 recordings. Which isn’t to diminish his less frenetic instrumental contributions to other tracks—the sped-up piano solo on “In My Life” might be the most famous, but there were plenty of other notable ones, like the honky-tonk piano on “Good Day Sunshine” and “Lovely Rita.”

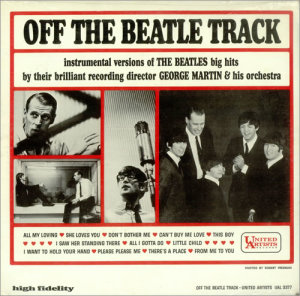

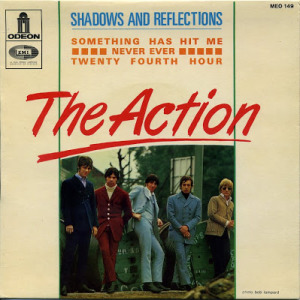

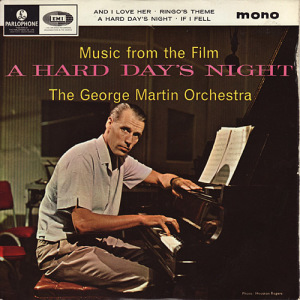

As great as Martin’s contributions to the Beatles were, it’s a little curious that he didn’t make many truly notable records with other rock groups in the 1960s (or the 1970s, Jeff Beck’s early fusion albums excepted). He didn’t record much rock before working with the Beatles, making his greatest mark as a producer of comedy discs with Peter Sellers. His work with other Merseybeat groups like Gerry & the Pacemakers and Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas produced some enjoyable hits, but was extremely lightweight and conventional compared with even the early Beatles recordings, with little in the way of remarkable ingenuity. He never abandoned middle-of-the-road pop, as his hits with Cilla Black and Matt Monro demonstrated. His own versions of Beatles hits that were released under his name were surprisingly bland, even square. His tracks with the one ‘60s rock group he produced other than the Beatles who had an assertive, guitar-oriented sound—mod band the Action, who never had a big hit, despite gaining a cult following that lasts to this day—were punchy, clear, and balanced, but don’t bear a specific imprint or utilize particularly crafty production touches.

It may be that the Beatles were so all-consuming that Martin had little left in the way of extraordinary contributions to other acts with whom he worked. Just as it’s certain that Martin brought out the best in the Beatles, it’s possibly even more certain that the Beatles brought out the best in Martin. While he earns the title of fifth Beatle, there were of course many others who made crucial contributions to their music and career, starting with Brian Epstein. Numbers two through ten on my list will be discussed in my next blog post.

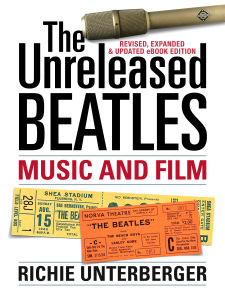

Critical description of all known unreleased Beatles recordings, their most crucial unissued film footage, and more. Updated with 30,000 more words to reflect newly circulating material and additional information that’s come to light since the original edition. Click here or on the cover image above to order through Amazon.

As is the case with all your writings Mr. Unterberger, this blog post is entertaining, engaging, informative and compelling in it’s case for George Martin as “fifth Beatle”. However, I have always had a different point of view, one that has evolved from factual as well as purported or possible circumstantial events and data. George Martin is disqualified (IMHO) due to one facet of his relationship to the band; he had absolutely nothing to do with their live/stage performances. For me (and I will hold fast to this opinion forever) the one and only fifth Beatle was…..Stuart Sutcliffe. We can all speculate till we’re blue in the face, but I believe, had he lived, Stu would have continued in some capacity with the Beatles. There was only one time in history when the Beatle’s were a five piece unit….and Stuart was that fifth member. Peace out, Bart