Things might have changed now that they’re such collectibles, but when I was real young in the late 1960s, baseball cards were often considered wasteful frivolities. Maybe the stale bubblegum sticks that came with them were, but in my own case, the cards themselves were greatly undervalued aids for teaching me how to read. When I was five and six years old, the kids’ stories in textbooks weren’t really sparking my appetite for learning. No, the first things I avidly read on my own were Peanuts cartoons and — the backs of baseball cards. You’ve got to start somewhere, and while I probably would have learned to read (and write!) with the moralistic kiddie tales in first-grade lessons, nothing stokes the hunger for knowledge as much as subjects in which you’re actually interested. Peanuts, and baseball, were those things (the Beatles wouldn’t come until about two years later).

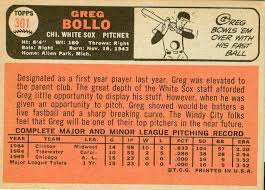

Looking back at the backs of the cards, you can tell how relentlessly optimistic the brief text was, as if every day was the first day of spring training, hope not so much springing as gushing eternal. The term “media spin” wasn’t in use then, but the concept was certainly used, and frequently, in building up every single player who’d been granted a Topps card, no matter how marginal their chances of becoming a regular. You knew someone was really marginal when Topps’ anonymous writer-cum-PR-person really didn’t know what to say in the little cartoons that accompanied the one or two sentences of text. Like this 1966 card for White Sox pitcher Greg Bollo:

Even back then, that struck me as a weird and kind of creepy image, like Greg Bollo had actually thrown a bowling ball at the hitter instead of a baseball, leaving the batsman with an irreparable hole in his soul. Topps’s loss for words was a pretty good indicator that Bollo might not stick at the big league level, and indeed he didn’t. Now that the Internet’s at hand more than 50 years later to fill in the gaps, though, Bollo’s story — and those of who knows how many other on-the-cusp players — turns out to be more interesting than the print that could fit onto the back of his baseball card.

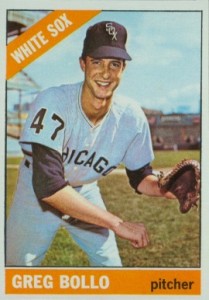

After pitching very well at the single-A level in 1964, Bollo was promoted to the big club and spent the entire 1965 season with the White Sox. It might be more precise to say that he didn’t play in the minors that year, since he somehow appeared in just 15 games. With no wins, no losses, and no saves, it’s safe to assume he was mostly or wholly used in mop-up roles. Was he injured for part of the year? Was he carried on the big league roster to give him experience, but not thought of as truly ready for the big time, and thus relegated to what we would these day call “low-leverage” situations? It’s pretty rare for a pitcher to be used so seldom over the course of a full year (and downright unknown these days) at the major league level.

Bollo spent most of 1966 back in single A, where he had a fair — not great — year for Lynchburg. You’re riding a strange yo-yo when you’re called up from single A to the bigs and sent back down to single A, a string made stranger by Bollo’s return to the White Sox in September. After a couple more no-decision relief appearances, someone took pity on the poor fellow and let him start the final game of the year on October 2, against the Yankees. He didn’t do too badly — giving up one run in four innings (though he walked three) — but that was enough to tag him with the loss, in a game the Sox lost 2-0. And as Bollo never got into another major league game, that was also enough to tag him with a permanent 0-1 lifetime record.

(As an aside, on the very last day of the season the previous year, the Yankees had dealt the only decision — a loss, again — to another hard-luck picture, Arnold Earley, who had managed to get into 56 games without a win, loss, or save before losing the final game of 1965 for the Red Sox. Read about that story here.)

Only 22 at the time, Bollo kept at it in the White Sox organization until 1970. He spent two years and part of another in triple A, but never did conquer his control problems. He wasn’t quite bowling them over with his fastball. But his brief time in the majors did generate that one indelible image, left behind in a closet or drawer by an older brother, and doing its share to cultivate literacy in a place where mainstream culture least expected it.

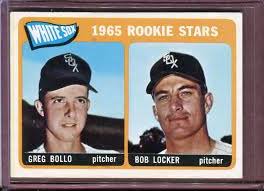

In contrast to Greg Bollo, the pitcher who shared his 1965 rookie card, Bob Locker, enjoyed a fairly long and successful career, appearing in 576 games (all as a reliever) and pitching for the Oakland A’s in the 1972 World Series (which the A’s won).