As I wrote in my December 31, 2018 post listing my favorite reissues of 2018, expanded editions of classic, or even not-so-classic, albums are a growing presence in the record industry. At this point, in fact, it seems like almost every vintage rock act has an expanded edition of some sort in their catalog. At the extreme end of the scale, it can run to huge, and hugely expensive, multi-disc sets, like the recent seven-disc White Album box or, on a more cult level, the seven-disc set box for the Stooges’ Fun House. At the chintizest end, it can mean just one additional marginally different alternate take, or one B-side.

While the biggest boxes tend to go to very popular acts, that’s not a hard and fast rule, with many cult artists getting the very extended treatment. Besides the Stooges, for instance, the entire Velvet Underground catalog has been granted expanded editions, some of them running between four and six CDs. Even artists who neither sold that much nor have much left in the vault get spruced-up single CDs, like late-‘60s Elektra groups Clear Light and Eclection. And Skip Spence’s Oar, supposedly one of the lowest-selling major label LPs of the late 1960s, was recently honored with a three-CD edition—perhaps the unlikeliest huge expansion of an album to date, though it’ll no doubt be outpaced by an even more obscure record in the future.

What makes for a really good extended edition? Ideally, it should hit all or at least some of the following bases:

Additional material, whether studio outtakes/B-sides/rare compilation-only tracks/live recordings, that’s of considerable historical interest/value to enhancing appreciation of the core album;

Additional material that, besides being rare in the manner outlined above, is also very good and enjoyable to listen to, even granting that it’s seldom-to-never going to be as good as the core album it’s embellishing;

Thorough excavation of all the reasonably interesting/quality additional material that can be added to the core album, even if it takes several discs to do so;

Top-notch packaging, particularly in the way of detailed historical liner notes, with fine/rare vintage photos, ads, posters, label/sleeve reproductions, and other memorabilia being useful bonuses.

Some expanded editions come close to hitting this grand slam, but none of them really do. That’s not necessarily the fault of the compilers, labels, or artists. Sometimes every damn last thing is included, but the additional material’s just not massively interesting/enjoyable/notable. Sometimes great unreleased tapes known to exist are not legally available for clearance. Sometimes the artists themselves aren’t cooperating with the project.

I’ll look at some of the notable failures of expanded editions to meet their potential in my next post. But the bulk of this post will be devoted to some of my favorites, and why, in different ways, they meet at least some of the goals to which all such retrospectives should aspire. No doubt some of your favorites will be missing. But keep in mind that it’s a list of personal favorites, not one that ticks off how well the set was mastered and assembled and how its importance is judged by the community of music critics and listeners as a whole, regardless of how much I like the music.

As it happens, two of the best expanded editions came out last year, and took the top two positions on my 2018 reissue list. #2, but #1 as far as ideal expanded editions go, was Liz Phair’s Girly Sound to Guyville. Despite the different title, this is essentially an expanded edition of her 1993 album Exile in Guyville, which occupies disc one of this three-CD set.

But the real attraction of this release—not a box, just a regular CD-sized package with three discs—are the two CDs of the so-called Girly Sound tapes, which Phair recorded on her own on a four-track in her bedroom. These predate the recording of Exile in Guyville, and include not only different versions of seven Exile songs, but more than thirty others, some (but not many) of which she’d redo for post-Exile albums. These come close to meeting all four of the criteria for the ideal deluxe edition:

Considerable historical importance. This is almost as thorough a document as possible of her evolution before her debut album, both with the different versions of Exile songs but also, even more crucially, the many songs that didn’t make it on there or anywhere. (As to why it’s not completely thorough, see two paragraphs down.) And they’re much different sonically than the Exile material, with their solo lightly-amplified-guitar-and-voice intimacy (though Exile wasn’t gaudy or over-produced).

Extremely high-quality, enjoyable bonus material. I’m not putting detailed reviews of the music for the albums I discuss in this post, and you can read about that aspect of Girly Sound to Guyville in my extensive rundown of the record on my best-of list. But the two discs of home tapes have both very good, sometimes great, songs and good performances, in considerably better sound quality than their bootlegged versions. They are discs I’ve listened to over and over, which is rare for tracks augmenting the core classic album.

Almost everything known to exist was included. Here’s a prime example of how two items are missing, but not through the fault of the artist. Two songs from the Girly Sound tapes, “Fuck or Die” and “Shatter,” that have circulated unofficially are not included. That’s because they incorporate some lyrics from Johnny Cash’s “I Walk the Line” and the Rolling Stones’ “Shattered,” and couldn’t be cleared for official consumption.

Good packaging and annotation. The fairly fat booklet features extensive interview material with Phair, Exile in Guyville producer/bassist/drummer Brad Wood, Casey Rice (who also plays on Exile in Guyville), and some more obscure figures who helped build awareness of Phair’s work. However, in part because it’s not LP-sized, graphically the booklet’s not as impressive as most expanded edition notes are, with virtually nothing in the way of illustrations. If it’s a choice between good notes/documentation and fluffy/minimal notes filled out with big photos, however, I’ll take the non-augmented notes every time.

To be honest, this really could have been a two-CD set with just Girly Sound material. Almost anyone who gets this already has Exile in Guyville. The conundrum is, though, that if it just had the Girly Sound stuff, it wouldn’t be an expanded edition, and maybe the participants wouldn’t have been as motivated to produce liner notes that were as thorough. The third disc probably didn’t up the price up too much; the CD set was selling for a pretty reasonable $20-25 when it came out, though I wonder if it’s already gone out of print, since it’s already not easy to find new online.

#1 on my 2018 reissue list — but not quite as impressive as Girly Sound to Guyville viewed purely from how it fulfills an extended edition’s mission — was the seven-disc box of the Beatles’ White Album. Three of the seven discs didn’t interest me much — two of them were of a new (and hyped) mix of The White Album itself, and the third a Blu-ray with mono and 5.1 versions. But four were largely comprised of unreleased material, three of them devoted to 1968 studio outtakes (almost all of which hadn’t even been previously bootlegged), and the fourth to demos the group recorded at George Harrison’s house shortly before the White Album sessions started.

More than anything else, that disc of demos—the so-called Esher demos, in honor of the name of Harrison’s home—is what puts this in the top echelon of expanded editions. I’ve written about them at length in my book The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film, and you can read that section here. But for now, it’s sufficient to note that they’re the most important body of unreleased Beatles material, the 27 acoustic-oriented tracks showing them in an unplugged, loose, and friendly frame of mind. Crucially, it’s also a disc you can play over and over for sheer enjoyment—as I did when most of the demos got bootlegged back in the early 1990s. Now they’re in appreciably better sound quality, and available for all the world to hear, not just us clued-in cats who seek unofficially circulating recordings.

The three discs of studio outtakes have enormous historical value, but aren’t, with maybe a few scattered exceptions, things you’d want to play as often or repeatedly. And it’s not a thorough presentation of everything known to exist—there are so many multiple takes of White Album songs that you’d probably need a car trunk to hold them all on compact disc. (Maybe those will be made available to the public on the 100th anniversary of The White Album, though none of us will be around to hear them at that point.)

There’s also a 164-page hardback book that, a little surprisingly considered how much has already been written about the Beatles, is very good; has a lot of information, intelligently relayed; and has plenty of interesting graphics.

The Beatles were at an advantage when devising a box like this, of course, because they had such a big well of interesting unreleased material from the White Album era to draw upon. That wasn’t the case when they put out the only other deluxe edition produced for a Beatles album, the Sgt. Pepper box, where the outtakes weren’t nearly as numerous or interesting (or as variant from the official versions, as the ones for the White Album sometimes were). Another icon of the era, however, had an even bigger reservoir of unissued material to tap for the next deluxe I’ll cite.

It’s arguable whether Bob Dylan & the Band’s The Bootleg Series Vol. 11: The Basement Tapes Complete is even an expanded edition. None of it, after all, came out on a “proper” album, if you take that to mean an album released relatively soon after it was recorded. Even the 1975 official compilation of Basement Tapes—issued a good eight years after the tapes were actually taped—isn’t quite the core of this six-CD set. The 1975 Basement Tapes, for one thing, had eight Dylan-less Band songs not on the box, and five of the songs on the 1975 double LP were given overdubs for that release.

I think it’s safe to guess that these distinctions don’t matter too much to most—maybe even almost every—listener who’s interested in The Basement Tapes. They’ll probably consider The Basement Tapes Complete to be an expanded edition of whatever they have, whether it’s the 1975 double album or the five-CD Genuine Basement Tapes bootleg series. If you’re not disqualifying it, again it scores high in the key categories:

Vast historical interest, as it’s among the most mysterious periods of any major artist’s career, and a rare example of a star recording shed-loads of material during his prime, but not releasing any of it at the time;

A thorough exhumation of the available goods. A few very lo-fi tracks were left off, but it still included a whopping 138, some of which had never even been bootlegged. And the lowest-fi of the tracks were thoughtfully grouped together on one disc. It’s true that the 18-disc collector’s edition of Dylan’s The Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965-1966 outdid this by including every damned last surviving studio take, a disc of hotel room tapes, and MP3 downloads of all his surviving 1965 live performances. That’s not included in this list because it’s not an expanded edition of a particular album, although it’s extensive enough to deserve this honorable mention.

Listenability. To the chagrin of some, I’m not such a huge Bob Dylan fan. And this six-CD anthology of Basement Tapes, I think even Dylan obsessives would admit, is uneven, with a big gap between the best of the material (much of which was chosen for the 1975 double LP) and the numbers that were obviously throwaways or goofs. But it’s pretty listenable overall, if not as compellingly so from start-to-finish as the Girlysound tapes or the Esher demos. You’re likely to listen to this at least a few times all the way through if you buy this in the first place, and some Dylan fanatics will listen to it many times without tiring.

Packaging: a hardback 42-page book of liner notes that, if not as huge as the one with The White Album (or for that matter the books/liner notes that the Bear Family label often includes in its box sets), are very informative. That’s complemented by a 122-page book of vintage photos and memorabilia, much of it quite rare.

While these are the three expanded editions that stand out to me as the class of the field, I’m also citing a few others I like a lot, even if they don’t touch as many bases:

The Moody Blues’ first album, The Magnificent Moodies (in the UK; as usual for those days, in the US, their first LP was similar but somewhat different), was “expanded” into a two-CD job by Esoteric. Basically, it was an excuse to not just add to, or double, the length of the original, but to quadruple it. The Magnificent Moodies was hardly a magnificent album, though it was pretty good as second-line British Invasion LPs went. However, in the era when Denny Laine was their lead singer and (with keyboardist Mike Pinder) writer of their original material, they did a lot of non-LP singles. Some of those were quite good, and all are essential to a fuller version of their pre-psychedelic/prog era, when their forte was haunting R&B/pop.

The first disc of this modest regular CD-sized package has The Magnificent Moodies and all of their non-LP sides, even adding a rare French EP cut and an early unreleased version of their big hit “Go Now.” The second disc is more in the “good to have” category than the “spin over and over” one, with lots—about thirty, in fact—outtakes and radio sessions, not to mention a Coke commercial.

But it’s a nearly 60-track overview that’s so extensive it would have been unimaginable when it was a struggle just to get all of the Moody Blues’ pre-1967 output in one place. Lots of small-print info and graphics are in the 24-page booklet, and a foldout of press clippings and postcard/ticket-type thingies are thrown in. It’s an example of how to do the best job possible without the big budget and size of a deluxe box. Some would argue that it should also include their two other non-LP singles predating Days of Future Passed (after Laine left), but then those are on—you guessed it—the two-CD expanded Days of Future Passed.

While I don’t want this to turn into a commercial for Esoteric, the same label also huffed and puffed up the self-titled debut album by the Move into an unimaginable size, without sacrificing quality. The thirteen songs of the actual LP comprise a relatively minor part, percentage-wise, of this three-CD, 65-track set. There are also both sides of their first two singles (both big hits in the UK); outtakes; demos and a local Birmingham radio session from January 1966, a good year or so before their first record came out; and an entire disc of January 1967-January 1968 BBC sessions, including a bunch of covers they didn’t put on their studio releases.

Yes, disc two is dominated by the kind of stereo mixes I find relatively inessential. But again, an info-packed booklet and foldout of press clippings gets the most out of the regular CD-sized format. Esoteric did a similarly bang-up job on a lot of other parts of the Move catalog, by the way; the two-CD Shazam adds about three dozen bonus tracks to an LP that only has six songs (albeit some of which are pretty long). Ditto for Procol Harum’s first album, whose ten tracks are the prelude to 27 bonus ones, even if a few of those are peripheral stereo mixes. We do get into quantity over quality in some respects with these Esoteric editions, but the best extras on all of these are things you want to play, and sometimes play a lot.

I’m not as big a fan of Nico’s solo stuff as I am of the early work by the Moody Blues, Move, and Procol Harum. But I like how the two-CD The Frozen Borderline compilation basically puts two substantially expanded editions together. Disc one features her 1968 album The Marble Index, with outtakes, alternates, and demos; disc two features her 1970 album Desertshore with a half dozen demos.

These are close enough in release dates to basically be an overview of her prime as a songwriter (remember she wrote little on her very worthwhile 1967 debut Chelsea Girl), with both albums bearing a heavy influence from John Cale, as both an arranger and instrumentalist. It’s true the Desertshore demos tend to confirm just how important Cale was because they sound so bare compared to how they’d develop after he worked with the material. But that in itself is of pretty vast historical importance, if you’re a Velvet Underground fanatic at any rate.

The LPs came out on different labels (Elektra and Reprise), which often complicates things in the reissue business. But luckily those labels are now administered by the same company, which removes the obstacles from packaging these in tandem. The liners aren’t as imposing as the others on this list, but get the job done with lots of info and first-hand quotes from Cale and others.

How could it have been better? They could have also added material from her BBC broadcasts on John Peel’s program in early 1971, though most people who want The Frozen Borderline would already have those on her Peel Sessions EP, issued almost twenty years before The Frozen Borderline. Much less forgivably, two alternate versions that appear as bonus tracks on the much slimmer 1991 expanded edition of The Marble Index are not on The Frozen Borderline. It’s almost as though they feared making the set a total success.

One of the best expanded editions was of a soundtrack LP, rather than a conventional album statement by one artist. The 2003 two-CD deluxe edition of The Harder They Come pulled off the difficult feat of making a classic album better by more than doubling its length with a second disc of eighteen reggae classics from 1968-1973.

In a refreshing counterpoint to the elitism that sometimes governs the selection of such compilations, it included not only additional tracks by artists featured on the original soundtrack (the Maytals, the Melodians), but also some of the first crossover hits to popularize reggae in the US and UK (Desmond Dekker’s “Israelites,” Jimmy Cliff’s “Wonderful World, Beautiful People,” Dave & Ansel Collins’ “Double Barrel”). Although Johnny Nash is sometimes derided as an exploiter/mere popularizer of Bob Marley songs, it also includes his big hit “I Can See Clearly Now,” along with his Marley cover “Guava Jelly.” There’s also Eric Donaldson’s original version of “Cherry Oh Baby,” covered by the Rolling Stones on their Black and Blue album.

Yes, the compilers of this edition had an advantage over most expandeds in being able to pick choice gems from the entire pool of the era’s reggae music, rather than cull leftovers surrounding a core album by one artist. But it’s done very well, also included decent if not huge liner notes.

This was also done, incidentally, for the Easy Rider soundtrack, whose two-CD edition almost triples the length of the original LP release, adding nineteen other late-’60s rock classics (including the Band’s original version of “The Weight, ” which is heard in the film, but couldn’t be used on the original soundtrack LP for contractual reasons). But although it’s a good listen, it really isn’t connected with the film, which itself wasn’t connected with a certain musical style, as The Harder They Come was with reggae.

To round out the releases given qualified praise here to an even ten or so, how about a “shout-out,” as the 21st century terminology demands, to expanded editions that include DVDs/Blu-R=rays as well as music CDs. That’s becoming more common as time goes on, and though it’s usually secondary to the musical portion, there are some real goodies.

Just a few months ago, the expanded edition of Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland also had a DVD documentary about the making of the album (in addition to three CDs, one of them comprised of outtakes/demos, the other of a live 1968 concert at Hollywood Bowl). That documentary was issued a long time ago as part of the Classic Albums series, but the opportunity was taken to add almost forty minutes of extra material. So there you have an occasion where “bonus” material’s added not just to the music, but also to the visuals.

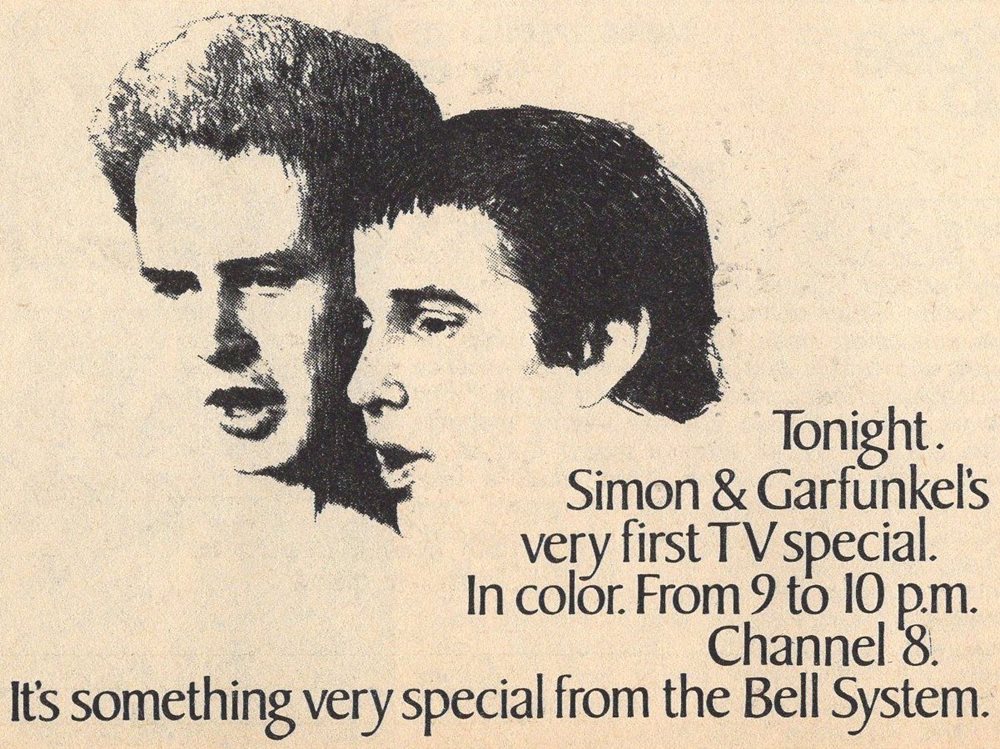

I like how Simon & Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water made the second disc a DVD featuring their 1969 TV special Songs of America, which is very interesting; had not been too easy to view; and was quite controversial at the time, mixing music with footage of contentious late-‘60s social turmoil. There’s also a documentary about the making of Bridge Over Troubled Water on the DVD disc.

Too bad, then, that no extra musical tracks are added to the actual album, when there are certainly some other studio and live recordings from the time that were eligible. In fact, a couple were even included when the album was part of the box set The Columbia Studio Recordings 1964-1970. But when it comes to extended editions, you not only can’t have everything—you never have everything.

But if even some of the best expanded editions have imperfections, some imperfections are more imperfect, and even annoying, than others. My next post discusses what not to do with expanded editions—even though such things are done all too often.