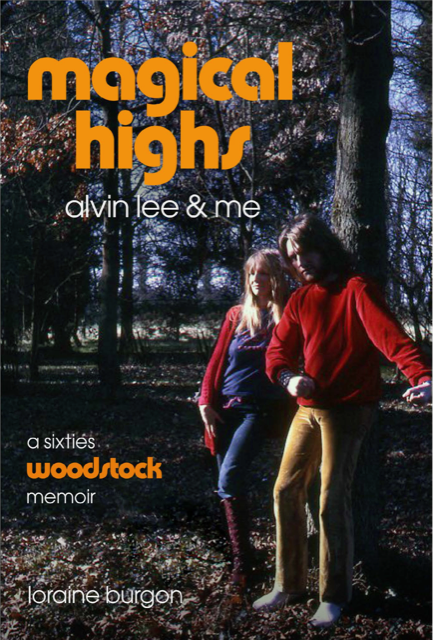

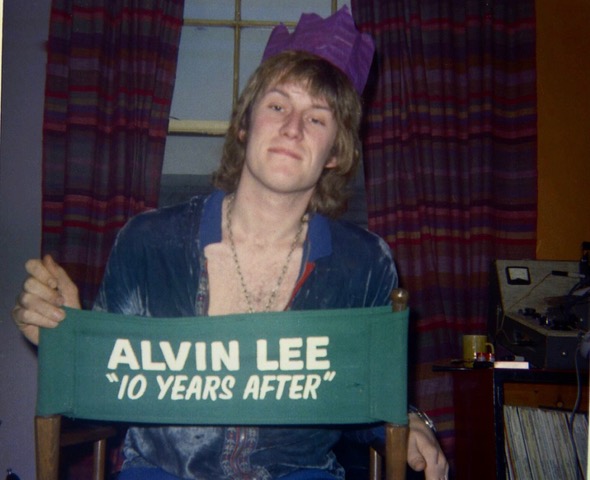

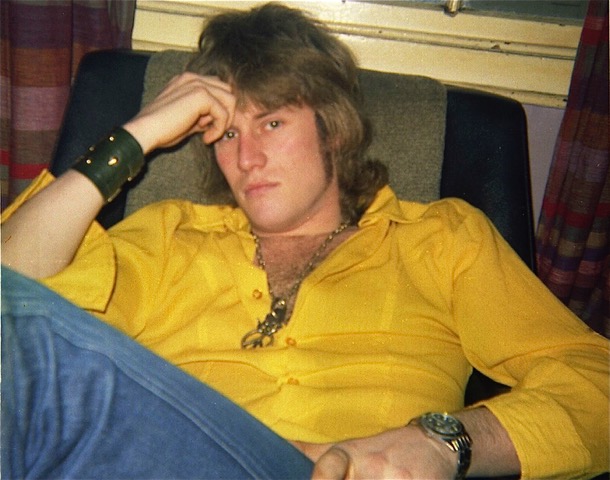

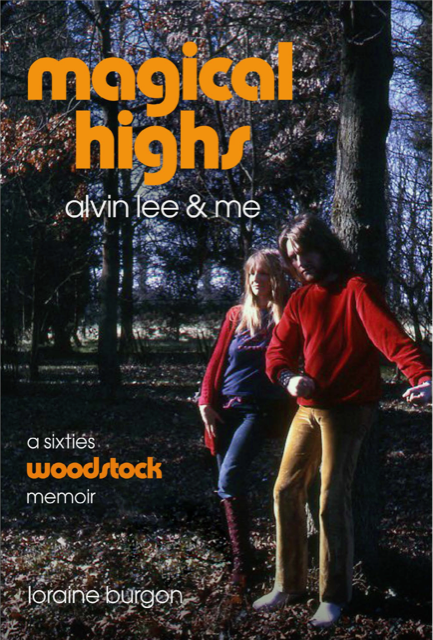

Loraine Burgon was Alvin Lee’s partner for about a decade from the early 1960s through the early 1970s, and while they didn’t marry, she was there for his rise from Nottingham cover bands to stardom with Ten Years After. Unlike many a rock partner/associate memoir, this is pretty detailed and well written, and—in a less common virtue—often attentive to the music, with plenty of accounts of concerts, recordings, and Lee’s evolution as a guitarist, songwriter, and singer. Although the pair separated in 1973, her love for Lee and his music is clear, though they weren’t ultimately suited for the long haul.

Considering how tight they were for a pretty long period, their relationship unraveled fairly quickly over the course of about a year when they moved to a large home (actually their second large home) outside of London. Both were caught up in extramarital affairs and Lee’s attention getting distracted by some drugs and interlopers. One of those interlopers was George Harrison, whose delights in earthly pleasures contrasted with his holier image as a devout follower of Indian religion. After leaving Lee, Burgon was involved with Traffic’s Jim Capaldi for a couple years, and then caught up in a zealous bust of Ronnie Wood’s home with Wood’s then-wife (both were found innocent after a couple trials). That’s where the story ends, and while those post-Lee adventures are covered in satisfactory depth, most of the book’s given to her journey with Lee, also documenting their pot and LSD use with unusual positivity for a rock memoir.

As Lee didn’t write a memoir, this might be as close as a book comes to an inside view of the guitarist and Ten Years After’s prime, particularly of their half-dozen or so years of peak popularity between 1967 and 1973. I spoke to Burgon about her book in March 2025, not long after its publication on Spenwood Books.

What was the main spark for writing a book about your years with Alvin?

Somebody had to do it. That was the conversation I would have with Alvin when we talked on the phone, or when we would email. We were still in contact. There was a constant conversation went on that said, what amazing times we lived through, and somebody should write that story. ‘Cause he was completely blown away with how it had been, and so was I. I would constantly say to Alvin, you go and write it. But he wouldn’t. So I thought right, I’m gonna do it.

As you and Alvin were in contact as you started writing the book, did he have much input into it?

We did have a lot of emails back and forth, and I got some picture of what he thought about it from some of those things. But I think you can’t try and write with too many angles going on in your head. You can’t try and think, well, I wonder what he would have thought and this is what I think. It says it’s a memoir, and that’s what it is. It’s not meant to be an Alvin Lee biography. Because if I’d written a biography, it would have been a quite different thing.

And I didn’t think when I started writing it that Alvin was gonna die. That was the furthest thing from my mind. ‘Cause he was still quite young, 68 [when he passed away in 2013]. So it never occurred to me that that was gonna happen.

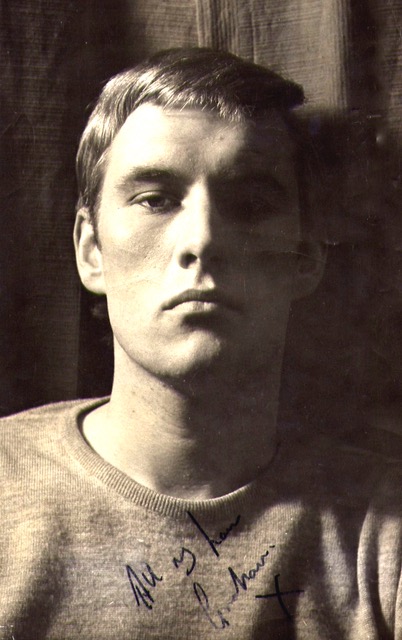

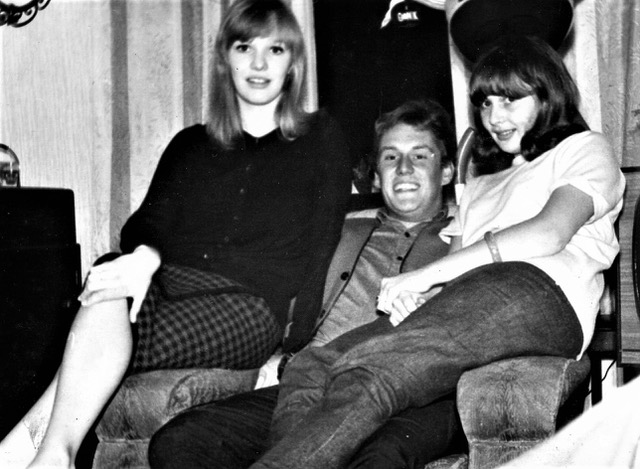

You first met Alvin in Nottingham when he was playing in the Jaybirds in 1963, under his birth name, Graham Barnes. You spent a lot of time with his family, and his parents were very unusual for the time in sharing their love of blues and jazz with him and his friends. Van Morrison’s parents were also big blues and jazz fans who played a lot of their records for him, but that sort of musical kinship with parents was pretty unusual for young rock musicians growing up in the British Isles at that time.

It was always astonishing to me that [Alvin’s father] Sam Barnes was really into the blues, and work songs. Kind of chain songs, as we would call them, when people in the penitentiaries were out in the fields. I wish to god I’d asked him why. But I was young, I was a teenager. I just thought it was amazing, and I remember listening to so much of it at Alvin’s home.

That was his music, [for] Sam Barnes. And he could sing along. I wish we’d recorded him! He had the most amazing bass voice, and he would sing along with all of this. So he really kind of had a blues soul. I have no idea where it came from. I know there were tours of these musicians, and they would go to Nottingham. So he did go and hear a lot of them. And [Alvin’s mother] Doris too, the pair of them. They were really into the blues.

There was also a jazz influence from his parents. Was that more his mother?

It wasn’t necessarily more from Doris. Les Paul and Mary Ford, this is something that Doris would play. I remember that being Doris. Also, Alvin had this brother-in-law who played jazz clarinet, George. So the first instrument Alvin played was the clarinet. When we went around to their place at Christmas, his sister’s, with her husband George, she’d be playing the piano, and she sang. I think they even performed locally, and George would play the clarinet, and Alvin would play guitar. So there was always a lot of music around for him in the family. It was a musical family.

Sam and Doris were really unusual. And they really heartened me; after my parents, who were incredibly uptight, to be around Sam and Doris was absolutely bliss. All his friends, [Ten Years After bassist] Leo [Lyons], all those people, they would come to his house to hear the music. Because what they were hearing was more interesting to them than what they would be hearing, say, on the radio.

Peter Green was a big influence on Alvin when he moved to London and the Jaybirds made the transition to Ten Years After. How was he inspired by Green?

It was just the fact that it was the blues. We hadn’t heard the blues being played live by anyone at gigs in London. It was the Marquee, and we’d only just got to London, and we’d only just gone to the Marquee. The Marquee was an incredible venue, especially at that time. He was playing with the John Mayall band. Mayall was extraordinary for having all these guitarists. He was like a training school for guitarists, wasn’t he?

He had a great intensity, Peter Green. I think it was his intensity and intention when he played that really probably struck Alvin. ‘Cause there was a lot of that when he played.

Green developed some amazing guitar sustain during his time with the Bluesbreakers, especially on the instrumental on the only LP he did with them, A Hard Road. Was Alvin influenced by his use of that technique?

I could imagine, but I can’t really say. I mean, [Alvin] experimented with the guitar so much. The thing that impressed me was it was only him plugged into the amp, and these speakers. He never had any effect pedals, or anything like that. He would sometimes play around with effects in the studio when they were recording things, some of those happened later on. But it was purely him to the amp through the speakers, and what he could get with that setup.

So he would be exploring all of those things. He really liked sustain, and he really liked feedback. That was very exciting to Alvin, yeah.

The whole group went through a big transition when they moved to London, changed their name from the Jaybirds to Ten Years After, and became more blues-grounded. What do you think the other members’ key contributions were as they became Ten Years After?

I do think that Leo and Alvin was really the heart of the band. I think it could have been other drummers. It could have even been other keyboard players. Or even without a keyboard player. But it couldn’t have been without Leo. There’s absolutely no way. That’s not to say I don’t think Ric [Lee, drummer; no relation to Alvin] and Chick [Churchill, keyboards] are excellent players. But just to say that, there’s something about the chemistry that Leo had with Alvin that was very powerful.

They were the two that started playing together when they were in their early teens. They had played together since 1960. There was certainly a musical dialogue between them that they never had to think about, it was such a strong connection. Although in bands it’s more typical for the bass and drum to have the strong connection that makes the rhythmic foundation, therefore leaving the more melodic instruments—guitar, voice and keyboards—to interact.

With TYA the foundation was Leo and Alvin. Some of that was the length of time and the experiences they had together before Ric or Chick played with them. They’d already been the Jaybirds, and the Jaybirds didn’t have Ric as the drummer. I saw the Jaybirds as a trio with Dave Quickmire, they were amazing. Dave Quickmire was an incredible drummer. That was a very powerful trio.

Dave Quickmire didn’t want to leave Nottingham. I only discovered from Leo in recent years, it was actually because he had a girlfriend and was engaged, and wanted to stay in Nottingham with her. Dave Quickmire didn’t come down to London. When they came down and did the play [as the band in a West End production of] Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, he didn’t want to. So that was when Ric came down and joined the band.

Then Chick had already been roadying for them. So it was a natural thing to bring Chick in and play keyboard. That was officially what he was doing to start off with. He was the only one who actually could read music. Not that that was ever useful with the band, ‘cause they never did play from music.

Leo was a really mobile bass player, bobbing up and down with nonstop frenetic energy.

It wasn’t that you just watched Alvin. You did watch Leo as well.

He was like the opposite of John Entwistle, as far as his stage presence.

Oh, absolutely (laughs). Unbelievable. So when [Leo and Alvin] would meet head to head…especially in “[Good Morning Little] Schoolgirl,” which became in a way, you could say, a set piece. The solo was set, but going head to head at that point. It was so powerful to see how they would play into each other like that. I think Leo’s amazing.

I recently read online that he’s decided this year to write his own memoir, which I’m really pleased about. ‘Cause he can write about Alvin before I knew him.

You saw Alvin’s creative process up-close more than anyone. You wrote that “he would learn new songs to cover and practice singing them at home, and sometimes he’d give me the lyrics so I could correct him or prompt when he forgot.”

We were definitely a team. But I wouldn’t be credited, no no no. All the lyrics were absolutely his. The thing that Alvin, I would say, was proud of, was the fact that his material was original to him. ‘Cause I remember in later emails, sending him things where people online had said, “Oh, Led Zeppelin, they took this riff from this old blues song.” Led Zeppelin are quite known for having taken things from earlier music. I would send Alvin that to him to amuse him, to go, this is interesting, isn’t it?

He would never have done anything like that. There was no question that he wouldn’t have. Yes, there were the songs like “I Can’t Keep From Crying Sometimes” [adapted from a number by gospel-blues singer Blind Willie Johnson] which came off of that one compilation album [What’s Shakin’, a 1966 LP featuring tracks by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the Lovin’ Spoonful, Al Kooper, and a studio-only group with Eric Clapton, Stevie Winwood, Jack Bruce, and Paul Jones; Ten Years After learned several of the album’s songs to use in their early repertoire].’That was credited to Al Kooper, which is very interesting, ‘cause Al Kooper didn’t actually write the original. Alvin told me once that he met Al Kooper, and Al Kooper thanked him for having bought him a house! (laughs) Which I thought was great.

But Alvin had a lot of integrity. His songs came out of him; he really wanted to do them well, and do them better and better. And sometimes it would be like, there was this song [originally recorded by others] that was very popular that they were performing. So he would want to try and write something that might replace that. But some of the more popular songs that they always did, they could never replace. Like “Help Me” [originally by Sonny Boy Williamson] and “From Crying,” “Schoolgirl” [Williamson’s “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl”], they became so much standard to them that everything else had to fit around that.

You also contributed a lot to their fan club magazine, The Palantir, under the name Vicky Page.

It sounded more like a writer, I don’t know, Vicky Page. So I did that starting in Warwick Square [where she and Lee lived in London in the late 1960s]. I got contributions from the rest of the band. I would nag them to give me contributions. There’s some really funny stuff. Alvin had it put on his website. the whole thing. There were maybe six editions. You could have seen them all on there. Unfortunately, his widow took them down not long after he died.

It was interesting to hear your memories of some of your favorite records when you were living at Warwick Square, since some of them weren’t too similar to Ten Years After and weren’t too popular at the time. Especially the Velvet Underground’s first album, and Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. How did you find out about the Velvet Underground’s first album (The Velvet Underground and Nico, aka “The Banana Album” in honor of the Andy Warhol-designed cover)? Not many people in the UK knew about it then.

How did we come to hear the Velvet Underground? I think to some extent, once Alvin went to America, he was exposed to Tower Records [the huge store on Sunset Strip]. As I write in the book, they’d let them run in Tower and pick up as many albums as they like. So they’d pick albums from what the sleeve looked like. So it might have been one like that. The other possibility is Simon Stable, wonderful Count Simon. He had his own record shop on Portobello Road [to this day one of the prime London shopping areas for offbeat merchandise]. He found all kinds of alternative music. He would bring Alvin stuff that was not mainstream music. So a lot of stuff came from him. There were various friends who bought music as well, who had their own little music interests, who would bring things in that way.

Would Alvin have been interested in that because it was so different from most other rock music of the time?

I think it was, because it was very unusual. I think it was because it was a very different kind of a record. It was the novelty of it. Well, not novelty, but the newness of it. He loved to hear music that would stretch his own musical imagination. And that’s what the Velvet Underground did. Things that weren’t predictable, Alvin wanted to listen to.

We never listened to kind of contemporary bands, really. We never listened to Led Zeppelin. Because if it was a guitarist especially, he just understood completely what they were doing, where they coming from, what their influences were, and everything.

Of course, that wasn’t the case with Hendrix. Hendrix was the only guitarist he ever listened to, really. Early on he listened to Eric Clapton a bit, and Peter Green, when we’d gone to see him live, that was such an influence on him. Jeff Beck a little bit, because we knew Ronnie Wood, so we listened to Beck-Ola a bit, that was quite a good album that we liked. He had pretty eclectic taste, in a way. The Small Faces’ Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake, that was a good album, we enjoyed that.

This Spanish guitarist called Juan Serrano, we loved listening to him. The photo on the cover of the album looks like he’s got six hands. We used to joke that he’d got six hands, because that was kind of how the music sounded. And then—I wrote about it in the book—we had that amazing experience. We were in San Francisco walking down the street, and we see a bar. And the guy’s performing live there! We went and saw him perform. It was so fantastic! There was nobody much in there. Twenty people. He used to, for some reason, do a fortnight there every year.

There were a lot of blues-rock bands in Britain when Ten Years After started out—John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Fleetwood Mac, Chicken Shack, and Savoy Brown were just a few of the more well known. I think something that set aside Ten Years After from most of them was they had more of a jazz influence, especially in their earliest albums.

He listened to a lot of jazz when we were first in London. He listened to George Benson a lot before George Benson was singing. Those albums of Benson when he wasn’t singing, he listened to a lot. He used to like to listen to jazz guitarists. But he could also see that if you got too jazzy, if you got too just jazz, that wouldn’t be a good direction to go in either.

I know he never felt like a frustrated jazz guitarist. What he absolutely loved was rock and roll. He did love to be doing that full-on rock and roll, and I don’t think there was a better rock and roll guitarist. When he would do Chuck Berry numbers, or Bo Diddley numbers, I’ve never heard anybody else except them do it any better. ‘Cause he just had such a feel for rock and roll. He never would have wanted to limit himself to jazz.

I liked the story in the book of how they played Woody Herman’s “Woodchopper’s Ball” to help get them a residency at the Marquee, because Marquee manager John Gee was a jazz fan. Playing the Marquee regularly was a big help in developing their following in London.

When he started to extemporize “I Can’t Keep From Crying Sometimes,” it started off ten minutes or something, ended up being twenty-odd minutes. But where he gets into this tuning down the bass string, the E string, and then bringing it back up again, that just happened at the Marquee. He started to do that one night and that’s not the sort of thing you sit at home and practice on an acoustic. It has to be on an electric guitar. And the Marquee was like his rehearsal room where he would do those things, ‘cause he was so comfortable there, and they were playing there every two weeks.

When you listen to one of the good live recordings of “I Can’t Keep From Crying Sometimes,” some of the really long ones—there’s a great one on an album from the Isle of Wight that’s incredible—I absolutely think that is constructed almost like a piece of classical music. I don’t think there’s another piece of rock music from that era that has anything like the structure and dynamics of that one track of theirs. The dynamic of it is to bring it right down, taking you to nowhere, bringing it back up, taking it higher, higher, higher. It’s structured like classical music.

It’s very long, so you never hear it on the radio. But I think it’s phenomenal. I think he just kind of tuned in to some place that isn’t on this planet to bring that through, that whole formation of that. It was extraordinary to watch him, and watch how it developed over that time.

I think Alvin was ahead of everybody. I think he actually was producing some music that still hasn’t been fully understood. I don’t think people have really got it, and really see what it is. ‘Cause you have to sit, like you would in a concert hall for a piece of classical music, and hear it all the way through, and take it in like that, like a concerto.

That thing of lowering it and lowering it, he was doing that in Nottingham with the Jaybirds when they were doing covers. He and Leo were already doing that. They were doing it with the Ray Charles numbers.

Like “What’d I Say”?

Yeah. He would take that down and then bring it up louder again. It was definitely a couple of Ray Charles numbers where they used that dynamic. That was the first thing I saw of them doing that dynamic, before they ever went to London and were Ten Years After.

Something the book clears up is the origin of the name Ten Years After. In the U.S. at least, the usual story is that it referred to the group starting ten years after Elvis Presley became big. The actual idea came from something completely different.

There’s a lot of mythology about it was ten years after Elvis, or ten years after this. No, it was just a headline, Ten Years After Suez. It was the Radio Times, which is the paper that tells you what’s gonna be on the TV. They were hunting around for names, and writing up a list of various names. Leo came up with Ten Years After and Alvin loved it, ‘cause he said, it’s abstract. It’s going to be something that people scratch their heads about. But it’s not going to tie them down to one genre of music. That’s what he didn’t want. He didn’t want to put blues in the name of the band. He didn’t want to make it anything that would be specific to a type of music. And Ten Years After isn’t. Ten Years After what?

That was one of the albums, Watt [sic; their sixth LP, from 1970]. I didn’t even know this, but donkeys’ years later on email, he told me, I never intended it to be Watt. It was supposed to be What, but in a way I’m glad it was, because that would have been too obvious.

When Ten Years After did their first album in 1967, it had covers and a few songs Alvin wrote that, as far as you know, were his first compositions. Did Alvin feel like he had to write quickly to fill material on the first LP (self-titled Ten Years After), or under pressure?

They had been in covers bands in Nottingham. He hadn’t been writing in Nottingham. But it was definitely the case that once he was given the opportunity, yeah, I’ll have a go, I’ll see what I can do. I remember him starting to write at Warwick Square, just with his acoustic guitar there. He would just sit down and think about words and write them down, and then he would play and find chords. Actually, they were quite short songs.

When they came to release that ridiculous single, “Portable People” (from 1968, which had an uncharacteristic psychedelic pop feel), there was no reason that they couldn’t have taken the shorter tracks off of the Ten Years After album. Some of those would have made singles. But then, Alvin never wanted singles. He really didn’t. He was definitely not interested in hit singles. Of course, the rest of the band would have gone along and had hit singles. And his management would, and the record company would. So that was a quite a big chain of energy coming towards him about it. But he resisted it pretty well, really.

There’s footage of them performing “Portable People” on French TV in 1968, and they don’t seem as engaged in the material as usual.

It was a joke. Everything about it, it’s very obvious it’s a joke.

The first Ten Years After albums were done amazingly quickly, at a speed that’s unimaginable today. There were just five days spent on their first LP.

I think it was the way they were used to doing records at that time. Most bands, initially, they all expected to. They would rehearse before they ever got there

I think it’s very interesting, this word studio. ‘Cause artists, visual artists studios, is somewhere where you go and experiment. Well, music studios didn’t tend to be in those days somewhere you went to experiment. It was somewhere where you pretty much know what you were gonna do when you got there. Because the expense of those studios, which all came out of the artist’s royalties of course, was very big. It was a very high hourly rate. So yeah, they wanted to get on with it and come out. So I don’t think they minded initially.

At first they were produced by Mike Vernon, who produced a lot of notable records in the British ‘60s blues-rock scene. He was most famous for producing the Bluesbreakers albums with Eric Clapton and Peter Green, but he also produced Fleetwood Mac’s early work, and David Bowie’s first LP, though that wasn’t blues-rock. You were at some of those early sessions. What’s your impression of Vernon’s role?

I think Ten Years After were really finding their way. Alvin was finding his way in the studio and how it all worked. I would say it was sympathetic, but it was more business-like. It was more, let’s get on with it, and do the job. Until a band had proved itself, until it had got a product out, and they were having good sales; then you got more leeway. Then the people who were producing were more willing to let them get high in the studio and just take their time, and not be too concerned about it all. Once they got away from Mike Vernon, and got away from using Decca’s studio, then there was more time taken. Because obviously there was money being generated by then, so it was possible to do that.

The great thing was that once they got away from Mike Vernon and Decca, it was a great sense of freedom that they got from being able to be in a studio and experiment with what was going on and have somebody who was more experimental with them. Gus Dudgeon [Decca engineer most famous for producing Elton John’s hit singles and albums in the first half of the 1970s], he was a really nice man. Andy Johns was really a major part of their recording as well. He was working with Gus, and then he also engineered for them.

Gus also co-wrote a song with Alvin for the first album, “Losing the Dogs.”

The thing about him was that he didn’t try to interfere with the process of what they were doing. He just wanted to support what they were doing. That’s the ideal producer, isn’t it?

Once they got to Olympic — well, Olympic was like the golden studio in London. It was how it was seen. It was an amazing environment.

There’s a lot in the book about their manager Chris Wright, who did a lot to help establish the band in both the UK and US. But also he did some business deals that might not have favored the band as equitably as they could have. Do you think the good outweighed the band in what he did for Ten Years After?

I think the good outweighed the bad. I know that Alvin, right up to his death, felt good about Chris. He never felt bad about him. Some of the others in the band, we all kind of knew they’d reached the point where, well, there was money issues that really ought to be looked into and all of that. And Alvin was like, well, you go and do what you want. But I’m not interested in that. He always had a good feeling towards Chris.

He and Chris got along. Chemistry is just something you can’t define how it comes about. Some people connect very well, and he connected very well with Chris. He just was the right fit for the band at that time. They’re all the same age; Chris Wright isn’t older than the rest of the band, although he always looked like he was about twenty years older. So they felt on a level with one another. It wasn’t like a Peter Grant. That would have been a manager and a half, literally and figuratively.

The fact of the matter was that they were all starting out together. So they had the same manager going in the same direction. Chris had grown up in the next county to Nottingham, so there was a lot of understanding of how their upbringings were similar. He’d gone on to university. Alvin, Leo, none of them went to university. Alvin wouldn’t have done it for all the tea in China, he couldn’t wait to get out of school, he was like me.

They had so many similarities, and he’d started his career in the north of England. When Ten Years After was first starting to get attention, they didn’t even have a presence in London. He realized that they had to have an agency in London because he had a hot property now. So they came down and started [with Terry Ellis] the Ellis-Wright agency before it was Chrysalis [which became one of the world’s most successful record labels of the 1970s and 1980s]. He just absolutely was the right person.

And yes, there may well have been things, like [shortly afterward with their US manager] Dee Anthony, that were a problem. Alvin was never that concerned about if he’d been overtly ripped off. It wasn’t a big thing for him, the money of it all. It was never the big thing for him. He never felt like that was his motivation. He always felt much more that the music was his motivation, and we wanted the managers to manage, and he wanted to hand all that over. He handed over all the household bills to me, do you know what I mean? He really didn’t want to be bothered with any of that. Right up until the end of his life, I’m sure that was the same.

It was interesting to read there was unreleased material from a live in the studio session in March 1968. You wrote about it positively in the fan magazine, but negatively in the book.

It must exist somewhere. I think it would have been horrendous. I don’t think there’s anything about it that’s worth retrieving. It was obvious, after a time, that how they played live with an audience created an atmosphere that, if you could capture that in the studio, might be really good. So they had their session there and invited friends into the studio to…but no. It was never going to be…I don’t remember it standing out.

I was surprised. I’d written about it in The Palantir saying how good it was and all of that. But I think that was just because people knew it was gonna happen, or knew that it had happened, and wanted to have some feedback on it. But I don’t remember it as outstanding. I don’t think there’s anything on there that would have been material for an album. I think that was very obvious.

There are some BBC radio sessions from the late 1960s that are kind of live in the studio, that circulate unofficially. They’re good to hear, there’s something a little looser about them on those recordings.

They were also looser live than they were…It’s difficult to get that loose in the studios. I think that’s why I love their live albums best of all. It amazed me the Fillmore East album [recorded in February 1970] didn’t come out until the 2000s. That was the one that Eddie Kramer [engineer/producer most famous for his work with Jimi Hendrix] recorded. It amazed me that they hadn’t released it at the time, and I can’t really work out why when I listen to it. But there was some reason why they decided not to release it at the time.

You note in the book that Undead, their live album recorded at the Klooks Kleek club in London in May 1968, was initially supposed to be a US-only release. That seems to indicate that the record label and management might have felt that the US market should be specially targeted, although their albums would chart higher in the UK than the US until the early ‘70s.

There was this kind of hardcore underground of blues fans in England. But it very much was kind of on an underground level. In a way the American market seemed much more like…first of all, it’s vast. But also, places like the Fillmore, that was really lifting them to a whole other level. They did universities around America too, that was their kind of early setting. ‘Cause they’d done universities around England.

Alvin was just thrilled that there was this audience out there that really listened to the music, that was the initial thing. The Fillmores were mindblowing to play at. Because (laughs), you know, people were high. It was a bit like I was saying, the idea would be a concert hall; people would just sit and listen. The Fillmores were the closest that that ever happened. The Fillmore East especially, ‘cause it was a completely seated auditorium. That was a brilliant auditorium.

Some of the best concerts I ever saw them do, they did at Fillmore East. Because the audience would have got high. I’m only talking about having a smoke. But the audiences would have had a smoke, so they were really focused. And Alvin would have had a smoke. So there was a real simpatico between them all. They would have really connected with one another. That’s pretty magical, to have venues that are like that.

Once they started to be more popular in England, then the venues were kind of assembly halls and concert halls. But they weren’t conducive to anything like that at all. The Marquee was a place where the ceiling was low, it was very atmospheric. But they couldn’t get more than a thousand people or something in, if it would be even that. Once you got to the Albert Hall, c’mon. It was built as a concert hall. It was never built for rock and roll.

It was amazing that they played both the Fillmores on the very first tour they went out on. Everything became different from that point of view.

So did their label (Deram in the UK, London in the US) and management want to concentrate on the US, where the sales potential was bigger and there was much more airplay for bands like Ten Years After on FM radio than they could get on British radio?

It might have been the case for the record company, and for Chris. It wasn’t the case for Alvin. For him, it was that the audiences were so exciting, and the venues. There were some venues with light shows in England, but not really anything on that scale. There was the Roundhouse and places like that, but once you got outside of London, no.

When he went to America they realized, this is gonna work. They really did come back from going to America, and being involved with the Fillmores and all of that, knowing that yes, there’s an audience for them out there.

I really think that at that point, [Alvin] was so pleased to come back to England, where he could go down the street and nobody really knew who he was. He didn’t want to lose that.

Things were a lot different touring and managing overseas back then. You write that Chris Wright was actually writing letters to his business partner Terry Ellis during the first US tour, because they thought it was too expensive to make Transatlantic phone calls.

They were writing letters to one another! I’m talking to you 6000 miles away, and I can see you. There was nothing like that. When Alvin went off for that first tour and they were gone for three months, I think I got like two or three postcards from him. That was it. It was very difficult for me, and it was difficult for them too. Yes, they had fun. But it was far from ideal. Alvin didn’t really like touring on his own.

When Ten Years After took off in the US, Dee Anthony handled their management in this country. He was involved in the management of a lot of top acts, like Peter Frampton and Joe Cocker. He’s a controversial figure, as some have felt he didn’t handle their careers and finances as fairly as he could have. For Ten Years After, do you think the good outweighed the band?

Oh, way way, way outweighed the bad. Alvin still really liked Dee, right up to the end of his life. He took people for who they were as people. What they were doing with his money…well, he was very lucky with that whole house deal [when a home he bought in the early 1970s sold for a lot of money]. That was a very lucky thing. ‘Cause he had so much money come into his life, like winning the football pools, as it was in those days. That gave him all kinds of options about what he could do, which he wouldn’t have had otherwise. Also, it just meant that he never had to concern himself about money at all, from when the band first started to take off right to the end of his life. It was never an issue for him.

That wasn’t true for the other guys in the band, which is why I think they would have got more upset about the money that went missing. But it wasn’t the case for Alvin.

So Dee and Chris were people that he liked. Dee was very smart. Dee got high with Alvin. Alvin kind of trusted anybody who got high with him. He started to learn that they weren’t all good guys. But he loved to be together and get silly with one another, and have a good laugh. When he wasn’t on the stage he wanted things to be light. That was who he was. He was a joker, he was a lighthearted person.

One of the things that I find disturbing about him, his legacy, now how he’s seen…He’s in all these endless pictures of him on stage with his guitar, the thrusting guitarist. He seems to become so two-dimensional to me. That was one of the other things that I wanted the book to show, was that there was a whole person here. There was a lot more to him than just that. Of course that’s the bit that people were excited by, and enjoyed, and I completely appreciate that. But it wasn’t who he was in total. When he was offstage, he wanted to be off.

You wrote that after their early work, “Alvin was now the one steering their musical direction while the others were not that clued up about what Ten Years After were actually about.”

That’s definitely true, but I don’t think Alvin actually had a plan. He didn’t see where it was gonna go. He was just following where his musicianship and his instincts and his talent were leading him, and [the others] were not suggesting another direction. They were not bringing anything else to the table. They didn’t bring other music to the table. So by default, he was the one in charge.

Were the others more content to keep on doing what had made them successful?

Yes, I think that’s true. I think there was a lot more kind of an approach of, well, we know what we’re doing now, so let’s just keep doing it. Alvin was definitely…he was getting…we’re becoming a musical jukebox, was the phrase he used to use a lot. We’re like a musical jukebox. He understood that was what Ten Years After fans wanted. But he didn’t want to carry on doing that for the rest of his life. But he wasn’t clear enough in his head to be able to say, well, this is the different direction that I want to go into.

Somebody like Sting with the Police—he absolutely knew that he wanted to be more of a jazz player, from when he was young. So when they got to the craziness of their heights, he said right, I’m out of here. I want to go and play jazz. Well, Alvin didn’t have anything like that going on, anything that defined. But he just knew that he didn’t want to carry on going on these tours, making albums, endlessly…it was like being on a treadmill, really, to some extent. He definitely wanted to be able to and explore other things. I don’t know if he could have shifted the others. I think they’d just traveled their journey.

Although there was more money coming in, I don’t know that it would have really enabled him to be able to not carry on with Ten Years After. That big house [Hook End] was a massive shift of everything, it was crazy. We’d bought Robin Hood Barn [their first country home] for £24,5000; there was not the room in the attic big enough to build a studio. We sold it two years later for £210,00, nearly a tenfold increase, tax free. We bought Hook End Manor for £250,000. It had many outbuildings, including a barn. In that barn Alvin, Harold (my brother), Sam Barnes, and Andy Jaworski built a recording studio. On the Road to Freedom [Lee’s album with Myron LeFevre] was recorded whilst I was still there with Alvin, in 1973.

If we hadn’t sold that house, first of all, he couldn’t have built a recording studio. Coincidentally, more money had also started to come into Alvin from royalties in late 1973 /1974. So he didn’t need to tour with Ten Years After.

It could have been more lucrative for Alvin and Ten Years After, since as you write, there seemed like a conflict of interest when Chrysalis wanted to control his management, recordings, and publishing. Looking back, do you think it might have been good for you or someone outside of the band to point out these conflicts and help structure their affairs differently?

I do write briefly in the book about that one episode where we were in Chris’s office and him with a new contract to sign, and me saying can we take it to a lawyer. And Chris telling me, well, I’m not asking you to sign anything. He said to Alvin, “Don’t you trust me? Don’t you trust me, Alvin?” It was like, “Of course I do. Where do you want me to sign?” I was dealing with enough in looking after Alvin, in being there for him all the while. For me to try to do anything else wouldn’t have worked at all. And there was really nobody else.

One of the reasons that I was concerned about…well, it just seemed all the eggs were going in one basket. And all of their percentages were going out in one direction as well. It just did seem like a very obvious conflict of interest to me at the time. But of course, the rest of the band didn’t really know that all of that was taking place. It was when Chris took me and Alvin out to dinner—he didn’t take the others—and said to him, this is what Terry and I want to do. And offered what Alvin thought was a ridiculously stupid small percentage [0.5%, of Chrysalis] (laughs), which of course it wasn’t at all. It would have been fantastic to have had that percentage. But Alvin was disgusted by it.

So that was how much he knew about finances, or was concerned about them. Despite all of that, Chris he was still fond of toward the end of his days, and Dee as well. He just had great memories of them both.

You write about how badly Led Zeppelin, or at least some of them, behaved when they shared a bill with Ten Years After in the US in July 1969, throwing juice cartons at them while they were on stage. Why would they have acted like that? They were well on their way to being a huge act, and it seemed like there was no reason to feel threatened by or harass Ten Years After.

I think Jimmy Page really was impressed with Alvin, and that pissed the others off. I don’t know why. I have no idea. They didn’t need to be pissed off. They’d got a big career ahead of them. I don’t think there was any reason at all for them to feel like that.

This whole story about Alvin and the orange juice, I think is hilarious. You can just look at the reviews from that show to see that that didn’t happen. He didn’t get orange juice all over the neck of the guitar. That was kind of a strange myth. And various people have said, I did that, oh I did that, no I did that. It’s like, really? How many of you did actually do that?

I think Led Zeppelin came along and there was already Keith Moon in the Who, and there was already this idea that you behaved appallingly. You could do what the hell you liked, get to America and behave like the worst kid on the block. There was something about that that was going on for them. I think Keith Moon was a big influence on all of the bands to think that, oh, it’s carte blanche! We can behave like the naughtiest school boys we’ve ever imagined being. Alvin wasn’t like that, and Ten Years After were not like that. But yes, those other bands would behave in those outrageous ways.

If you listen to what Robert Plant said in later years, he always feels like it was the others, that he was just kind of pulled along with it on some level. He was a much more sensitive person. Jimmy Page, I don’t know. I know that he did really admire Alvin’s playing.

They were extremely competitive with one another in England. Not consciously. I don’t think it was a conscious thing, but Ten Years After did have this wanting to blow other bands off the stage attitude. That was definitely one of their go-to ways, especially to start off with. When they played somewhere like the Windsor Jazz Festival in the afternoon, they really wanted to leave an impression that would make it hard for the rest of them to follow. Once you’re a headliner, you don’t have that kind of…’cause you’re the headliner. Then you’re looking at other people who come before you. But they definitely wanted to, when they were still playing to other people being headliners, at these early festivals.

As you wrote, Jimmy Page did apologize to you for his behavior a few years later.

He was alright, Jimmy Page. I liked him. But yes, it was John Bonham, and [Led Zeppelin road manager] Richard Cole. Have you read his book? It’s the only book I’ve ever got through like a quarter of it or a third of it and thought, I don’t want to read any more.

Alcohol was never the best drug in the world, as far as I was concerned. It definitely didn’t improve anybody’s behavior. Alvin was not a drinker. Later on he was for a while, but he wasn’t when he was with me, because I was never a drinker. I was never a successful drinker, because I’m allergic to alcohol. Those that got drunk definitely were the bands that caused the biggest problems.

As a side note, there’s a funny line in the book about seeing Soft Machine supporting Jimi Hendrix at the Albert Hall in 1969, that “they seemed like good musicians who were determined not to play anything together.” I like their very early work, but I would more or less agree with that as they became more of a jazz fusion band.

That’s exactly what they sounded like at the time, it’s quite hilarious. They were playing amazingly, but not playing together (laughs). Yeah, that’s a line I was pleased with.

There’s an amazing statistic in the book, that Ten Years After toured the US 28 times in four years.

That’s what I’ve read.

An interesting point you make is that, contrary to the stereotype of women on tour causing problems, you and Ric Lee’s wife Ruthann actually stabilized the group’s behavior.

Well, it is true. It’s obvious, really. If you’ve got a woman there, it’s like coeducational schools. If you’ve got schools that are all boys, or schools that are all girls, it’s a very different energy than if you go to a school where they’re mates. The girls tended to be the more moderating force, controlling the behavior without doing it intentionally. But just because that’s kind of the way it would work.

Most guys, after the initial run of having a tour where they just jumped on every female that wanted them to, how long do you want to do that for, really? It’s not conducive to how you want to live as a human being. I wouldn’t have thought it would be. That’s what I got from Alvin. He lost his enjoyment for that very early on.

One interesting passage from the book is your account of their concert in St. Louis, right before Woodstock, where they played for a mostly African-American audience. It took a bit, but you remember Ten Years After won them over.

I just think that there isn’t any color in musicians. At that time, musicians were not aware of color. At Woodstock – you’re seeing Sly Stone, you’re seeing Santana – there was never any question that people would have found, oh this is too mixed, or anything like that. It wasn’t like that. The audiences were relatively mixed, or were more mixed. They weren’t so segregated. Just overall, it was, musicians are musicians.

I was briefly with Jim Capaldi, with Traffic. Rebop Kwaku Baah, who was their conga player, was amazing. He was African, he was incredible. And the bass guitarist, Rosko Gee, fantastic musician. They were a mixed group. I didn’t think at the time, oh, this is good, here’s a band with…it didn’t matter. It was the musicianship that was what was important.

The controversy about these things has perhaps come later. At the time, I don’t think there was any controversy about them playing the blues. I think a lot of the blues musicians were very grateful when there were covers of their music, because the royalties did go to them. It brought them fame. I think everybody lifted everybody up.

Especially after the Woodstock film, where Alvin was spotlighted in their performance of “I’m Going Home,” it seemed like he overshadowed the rest of the band, though that wasn’t his intention. Considering he was the focus not only as the lead guitarist and singer, but also because of his visual flamboyance, do you think that could have been avoided?

I don’t think there was any way that could have been avoided. It was inevitable. Alvin didn’t want it. It was the way it happened. He was very, very charismatic. He was an effortless singer. His guitar playing was the focus of what most people saw, but he sang effortlessly. He didn’t do vocal exercises or anything like that, or have any singing lessons. He just sang very expressively. He sang from his heart, in the same way that he played his guitar from his heart.

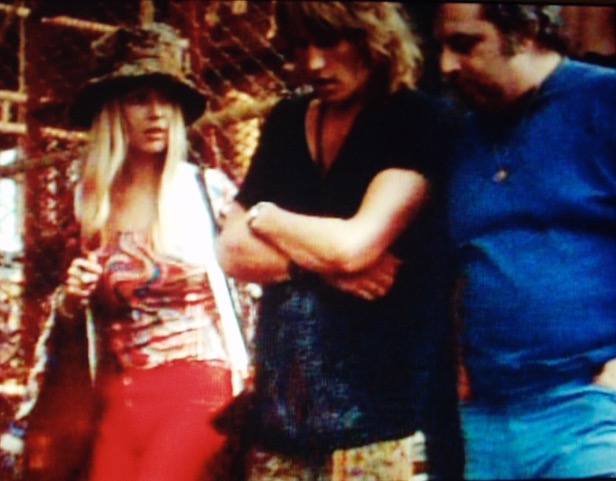

You and Alvin are briefly interviewed in the 1970 movie Groupies, which included footage of some British acts and women who were following them around. It probably wasn’t the impression the filmmakers were aiming for, but those women’s lives come off as pretty sad. You write that you thought the film was going to be called Rock 70 and about English bands on tour in the US, though it ended up being quite different.

As I said in the book, I used to tell people I was a groupie, I’d only met him the night before, when they asked me questions. But that was a joke, obviously. I just thought, how would you talk about groupies, what would you say about them? They were very pushy when I was first out there. Then they got used to seeing me out there with Alvin, the ones who were around all the time. So that was no problem.

Probably they were looking for someone who’d stay with them, but not able to understand how to do that. But that film was very weird. Because nobody knew that that’s what they were filming about. I think Groupies was an exploitation film. [It does include concert footage of Ten Years performing “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl.”]

When you and Alvin moved in 1973 to Hook End, your second home in the English countryside, a number of people were regular visitors, one of them George Harrison. As some regard George as a sort of holy figure for his humanitarian and musical accomplishments, it might take some fans aback to read you describe how “the gap between his spiritual beliefs and his fondness for sex, drugs and rock’n’roll was confusing to say the least.”

I think people were surprised by what I wrote. But he’s not two-dimensional. He wasn’t a saint, and this was more about him and who he actually was. I thought it was admirable that despite the fact that he obviously was a very sexual being, he still had this fantastic relationship with his spirituality. I think that improves on him, myself. The fact that he was actually a full human being, a full man…he really was a person of all of his sensations. He wasn’t someone who was only going in one direction. I think that’s admirable.

I mean, he grew up in Liverpool. They were northerners. That was kind of par for the course, to be…[his first wife] Pattie wrote about it anyway in her book. She writes quite a lot about all the different things that he was doing with different women. That’s exactly what was taking place.

For some reason, that year, there was a lot of turbulence going on around relationships, and around the people that we knew. And that pans out into other people. It’s kind of a rippling effect that took place. But I would say that’s definitely the case. I think their marriage was already in trouble. Well, I’m sure it was already in trouble. ‘Cause he would come and stay for days, and he was only living ten, eleven miles away. So there’s no reason for him to be staying overnight, there’s no need for that. That was his choice.

Considering how close you’d been for about ten years, both romantically and in other ways, your relationship with Alvin unraveled pretty quickly in 1973, over the period of about half a year. It seems like it was a combination of how disruptive it was to unexpectedly need to move into a different home; enforced celibacy when Alvin was diagnosed with catching an STD on tour, although there’s suspicion the doctor treating him was letting that diagnosis linger; more and more musicians coming into the home, sometimes to use the studio or stay over, like the US musician Lee collaborated with for a while, Mylon LeFevre; and Alvin starting to use cocaine, though you were unaware of this at the time. Is that an accurate assessment?

Yeah. It was like a perfect storm of everything being not very good, for me personally. I felt like I was quite crazy at that point. I think that was kind of where I’d reached. Alvin, I couldn’t connect with him. We’d lost our connection. I think the cocaine was a lot to do with why we lost our connection, because cocaine is a very cold drug. I didn’t know that. I only knew that it wasn’t gonna be a good drug for Alvin, for sure. Because he was speedy enough. The last thing he needed was to have some substance enter his life that was gonna wind him up.

But I don’t think there was any avoiding the cocaine, because it was just so prevalent in the music culture at that time. Which is a real shame. There was some record producer, and I’ve never been able to find the quote again, otherwise it would have been in the book, who said that he felt when cocaine arrived with the musicians in the studio, that the music went out the door. He really thought it was not good for music, and I don’t think it was good for music. It certainly was never any good for singers. It didn’t improve singers at all.

So that was the big aspect to it. Then you can flip out, and do something as dumb as I did, at that point, when you’re under a lot of pressure. Then you do it in such a way that there’s no way back. That’s just how it is. It was a perfect storm of all those things. It was very sad, because it wasn’t long after that Mylon went home, and they didn’t really continue with what they doing, although I think what they were doing had some value in it.

The big thing that we’d forgotten with Hook End was the very thing that had taken us out of London. Which was, we wanted to be somewhere in the country, which was a contrast to everything else that was going on. Well, once you build a recording studio that people come to, and you have a house attached that’s big enough for musicians to stay in, you’ve actually brought the city back out. Because those musicians don’t want to drive back into London every night. There’s no way that was gonna happen. So you’ve recreated what you ran away from.

In one of the book’s final sections, you write about how you and Ronnie Wood’s wife of the time, your good friend Krissie, had to suffer through two court trials after police made a drug raid of Ronnie’s home in 1975. You write that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards wanted you to plead guilty to get it over with, which you didn’t; you were both found innocent after a lengthy ordeal through the legal system. Jagger and Richards, one would think, would know the consequences of pleading guilty, having been harassed themselves on various frivolous drug-related charges that could have prevented them from touring the US.

I thought it was pretty appalling. It didn’t improve my view of them at all. It did me a lot of good ‘cause it woke me up. It wasn’t nearly so good for Krissie. I don’t know that she ever really recovered from it.

You also observe how Ronnie Wood seldom got songwriting credits with the Rolling Stones, though his contributions might have merited more.

Absolutely. I think he deserved it, because I think he had a lot of talent. Those two solo albums that he did, before he joined the Stones were really good albums. You can hear on those albums the basis of what he contributed to the Stones. It’s already there on his albums. He wasn’t so interested in the money. He was a bit like Alvin in that sense.

Unlike many couples, not just in the music business, you and Alvin did stay in contact and maintain friendship after you separated.

We just always had that connection. The connection didn’t separate with that. It did for a year or so after I’d left, although we still had phone calls. There still were times when we spoke to one another during that time. I went back to the house once during that time, or a couple of times, ‘cause my brother was still working for him.

It wasn’t only the death of our own relationship. It was also the times that we’d lived through. Because when you’re young like that and you live through extraordinary times like the ‘60s were, well, you’re never gonna be able to have anything like that experience with anyone else. It’ll never happen that you’ll have those level of experiences with another human being. So the bond you have formed at that time is so strong, it’s so powerful.

There had been a lot of connections between us. I’d gone and seen him in Spain when he was with [his partner] Evi three or four times in the early 2000s, and met up with him a few times. When I rang the doorbell, and he opened the door, he just held me and held me and held me. Because that was how it always was when we would see one another again. The love between us was always there. You know, love doesn’t die. It can change, and you’re no longer the people that you were. Well no, you are the people that you were. That’s the point of really, isn’t it. That in your core, you’re still the same people.

I always think, how can you say you really love that person, and then say, I hate that person? And cut all that off. You can’t cut it off. The love is still real, ‘cause love is always real. That’s how it is.

Something that sets your memoir aside from many memoirs by partners and associates of star musicians is that there’s a lot of description of the music. There are deep details about the gigs, the songwriting, the recording sessions, the equipment, and more. In many such memoirs, there’s the impression the author didn’t pay much attention to the subject’s music, or sometimes was even indifferent to it.

I love the music. I just loved it. I felt really blessed that I was on the road with Alvin and able to hear them every night. It was never boring to me. I was always at the side of the stage. I never went off to the bar. I didn’t drink! I didn’t want to watch the first number, and then go and talk to somebody else and come back. It didn’t occur to me. I was there for the music, I loved his guitar playing and his singing. It was completely that I loved his music. I know that not everybody who was involved with the band loved the music. But I did 100%, so I didn’t want to miss a note. I didn’t want to miss any of it at all.

I suppose that’s one of the reasons we were so close, because I did love the music so much. I mean, I was astonished in Pattie’s book that when they did the concert for Bangladesh, she only went in the evening. She didn’t go in the afternoon, when they played the afternoon concert. I was incredulous. I’m like, what?! Why would you want to do anything else when [George Harrison] was doing that? ‘Cause it wasn’t like he was playing endless gigs. I just didn’t understand her, why that would be the case. So no, for me the music was so important.

When they were the Jaybirds in Nottingham when I met him, I loved to go and see the band play then. I loved to travel in the van and go and be at their gigs. I loved being at gigs. That’s why it was so difficult for me at those early gigs when we couldn’t afford for the “old ladies to go out,” that I wasn’t able to go. It was really very difficult for me, ‘cause I really wanted to see those gigs. I wanted to see all of it.

I shouldn’t say it, because it makes it sound like the only thing that made music any good. But because I’d had a smoke, I was focused. Because I loved to dance, that’s what I was doing. I would dance all the way through a gig. I would get as hot and sweaty as Alvin did. But I would be somewhere at the side of the stage, hidden away from the audience. Except for Fillmore East. Fillmore East, they’d have seats up in the balcony I would go and sit in. That was good. But mostly, I was at the side of the stage hidden away from the audience. I didn’t want to be seen dancing, it wasn’t like I wanted to get on stage and dance. But I wanted to be able to dance. I was dancing before I met Alvin.

Do you have any thoughts on Alvin Lee and Ten Years After’s legacy, and how your book might help preserve it?

That was one of the things I hoped, that it would bring Alvin back into people’s consciousness and Ten Years After back into their consciousness. That was really one of my side wishes. But my impetus for writing was really more that I knew this story had to be written. I think they’re not as well known as they should be. On the other hand, their music is…well, if you have tracks that are twenty minutes long, fifteen minutes long, twelve minutes long, it’s very difficult. The radio’s not gonna play ‘em. So it’s kind of limited how they can be heard, which is really a shame.

I do believe there are universities in America that play a lot of their stuff. I have heard that. But not in England. It’s very rare to hear Ten Years After on the English radio. I know “I’d Love to Change the World” has been re-recorded by quite a number of people. In recent times, some other people have recorded it. It’s in coffee shops now in San Francisco, I hear it. But that’s ‘cause it’s been in a couple of movies.

A song that “I’d Love to Change the World” is much different than the bluesier sound Ten Years After started with. Do you have any thoughts on how things might have been different had he been able to pursue more of those different directions?

He went on, and he recorded a lot of other albums afterwards. But I saw him the middle of the ‘80s, and when he came offstage, he said, god, I’ve just realized, I’m still playing all the same old numbers. I said yeah, but they’re great old numbers. Of course you should still be playing them. Part of that was, we talked about this—he went to see Jerry Lee Lewis when he was in his country and western phase, and was playing country and western music. And Alvin wanted to see him play rock and roll when he saw him in London. He came out from that concert thinking, I should keep playing my music. ‘Cause that’s what people want to come and see, and I can add other things to it. But I should play the core of what Ten Years After played when I perform.

So that was always something that stuck with him, right up to the end of his life. He would still play “I’m Going Home” at the end and all of that. Because he felt, well, people come and see Alvin Lee to see those things, like he’d gone to see Jerry Lee Lewis. Which is a very considerate way to look at it. He did always bring in new songs. If he was recording something new, he brought it in.

Some of that live music of Ten Years After, if you’re gonna be a listener, you should treat it like it’s a classical concert, and just give it your full attention. This isn’t music to put on in the background. This isn’t music to have as a backing track while you’ve got friends there and having dinner and a drink or two. Because that’s what we did in the ‘60s, so much more. We would get together with friends, have a smoke, listen to an album from beginning to end. That’s what we did with the Beatles’ White Album. It was fantastic. That’s how you treated music. You wanted to listen to the whole thing. Astral Weeks, that was a whole album you wanted to listen to. You didn’t want to just have it going on in the background, and wander around and carry on doing what you’re doing.

Superb interview that makes you want to put TYA’s records back on the turntable. And to read the book as soon as possible, the originality and depth of which you highlight well, in a genre where too many books are content with, let’s say… anecdotal anecdotes. When will your list of the 10 best rock partner/associate memoirs be published?

Thanks. I hadn’t thought of making a list of the best rock partner/associate memoirs, but it’s an interesting idea to consider for a future post. There are many disappointing ones, but a few good ones.

What a wonderful interview. Loraine must be a favourite person to talk to? Open and honest, not holding back.