Just as the last couple decades have seen more music reissued than anyone expected, so have the last few years seen documentaries that no one could have predicted on cult artists of all stripes. Like John Fahey, for instance. For all the respect he’s given throughout the alternative music spectrum, he wasn’t filmed or interviewed all that much, which must make constructing a full-length feature a challenge.

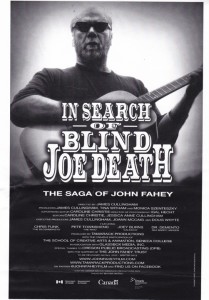

The hour-long In Search of Blind Joe Death: The Saga of John Fahey has actually been out a year and a half, and I have to admit I missed it the first time it passed through the San Francisco Bay Area for the 2012 Mill Valley Film Festival. Fortunately it screened at San Francisco’s Roxie Theater last night (July 9), and here’s guessing there aren’t many other cities that could draw 75 or so paying customers to a Fahey documentary (shown with a doc of similar length on Bill Callahan).

It speaks well of a documentary, I suppose, when it leaves you thirsting for more. While some people unfamiliar with Fahey might think an hour’s plenty of time to cover a guy who never sold many records, actually his achievements were diverse enough, and his character so quirky, that you want the music and stories to keep on flowing. That’s especially the case because the movie’s well done, interviewing several associates and critics — including Barry Hansen (aka Dr. Demento, who met Fahey when both were studying ethnomusicology at UCLA), fellow guitar virtuoso Stefan Grossman, third wife Melody, and Nancy McLean (who plays flute on his early track “The Downfall of the Adelphi Rolling Grist Mill”) — who are interesting figures in their own right. Star power’s supplied by Fahey fan Pete Townshend, a testament to how far up the pop ladder Fahey’s impact reached on occasion.

There’s not much vintage Fahey performance footage to draw from, but a few clips from various phases of his career are quite entertaining. The excerpts from a 1969 TV show hosted by one Laura Weber showcase some spectacularly skilled pieces. I know little about Weber, but she seems rather straight-laced and out of her comfort zone with John, especially when he explains the real-life origin of the title of “The Death of the Clayton Peacock.” After Fahey goes into the actual death of the slain peacock in more detail than Weber probably wished, the host observes what a sad incident it was; Fahey then quips, with no apparent remorse, that the creature’s expiration made for a good song title.

Five Fahey performances from the 1969 program “Guitar, Guitar,” hosted by Laura Weber, are on the DVD “In Concert and Interviews 1969 and 1996.”

Renowned for his enigmatic, at times surreal humor (especially as manifested in his song titles), Fahey could be acerbic as well as funny. One of the lower-fi concert clips captures him likening Stefan Grossman’s playing to that of a dainty lady with long fingers — and the jibe doesn’t seem entirely complimentary. John even titled one of his tunes “The Assassination of Stephan Grossman,” managing to misspell his rival’s first name in the process; Grossman responded by naming one of his compositions “The Assassination of John Fahey.”

As feuds go it’s not exactly up there with the Hatfields and McCoys (or even the Mothers of Invention and the Velvet Underground), and the animosity doesn’t seem to have run that deep, since they even planned a tour capitalizing on the assassinations. Unfortunately Grossman couldn’t do the tour for health reasons, and was hapless to prevent Fahey from claiming he’d actually assassinated Stefan when fans asked why the other guitarist wasn’t around.

A kinder side of Fahey is praised by Townshend, who remembers with fondness how John bothered to write him a letter (shown onscreen in the documentary) after hearing Tommy. Alas, according to the Who guitarist, it was obvious Fahey wasn’t a Who fan. I’m not so sure about that; Fahey was more open-minded to contemporary rock than some might guess, praising Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia, Country Joe McDonald, Jefferson Airplane, and the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper in a 1967 interview first published in Dust-to-Digital’s awesomely packaged five-CD Fahey box set Your Past Comes Back to Haunt You: The Fonotone Years [1958-1965].

This box set features the rare recordings Fahey made for the Fonotone label between the late 1950s and mid-1960s.

For all his oddness, Fahey took a lot of things seriously, and they’re treated with appropriate respect by the documentary. He was one of the first white fans to delve seriously into early blues recordings, and even helped track down one of the great country bluesmen who’d fallen off the radar, Bukka White, in the 1960s. He, along with similar free spirits like dedicated collector Joe Bussard (the first figure to record and release Fahey discs, and also interviewed in the film), even went door-to-door in black Southern neighborhoods to offer money for used records. As another interviewee points out, there was a real risk of getting roughed up or worse for doing that at the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement, when segregation was severe and their hunger for rare records could have been misinterpreted as something far more threatening or devious.

Too, the financial and health problems Fahey weathered near the end of his life were no laughing matter. A motel room he ended up living in is remembered by a visitor as “a dump”; he wouldn’t even bother to scrape off pennies that stuck to his back when he rolled over in his bed. He retains some intelligence and humor in snippets of interviews conducted in his latter years, at one point observing how his music somehow got categorized as “gothic industrial ambience.” The way he enunciates the term projects both amusement and faint incredulity, and perhaps a whiff of disgust as well.

For all its merits, In Search of Blind Joe Death: The Saga of John Fahey could have been more comprehensive. I would have liked more on how he founded and ran the Takoma label, which issued both his own best work and notable records by other adventurous acoustic guitarists like Robbie Basho. His pioneering DIY ethic is properly lauded — if Fahey wasn’t the first musician to do things entirely himself in the name of art above all else, he was certainly one of the earliest and most influential such innovators — but it would have been good to detail some of his major-label ventures as well. Some notable associates, like ED [sic] Denson, fellow Takoma acoustic guitarist Leo Kottke, and producer/manager Denny Bruce, were not among the interviewees. [Since I first posted this, Bruce told me that the filmmakers were planning to interview him, but canceled it when they ran out of money to do more filming.]

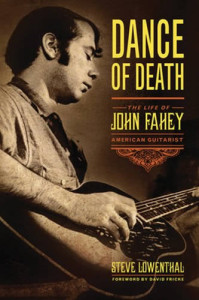

Hopefully some gaps are filled in by the new biography Dance of Death: The Life of John Fahey, American Guitarist, which I hope to read soon. I also want to see In Search of Blind Joe Death: The Saga of John Fahey on DVD, as according to the film’s website, it “includes extra performances and interviews with Fahey, Townshend, [Chris] Funk of the Decemberists] & more.” If nothing else, I want to be able to freeze-frame those shots of the letter Fahey wrote to Pete Townshend, which zoom by too quickly to digest in the theater.

Postscript: A few weeks after I put up this post, I did see the DVD. As is sometimes the case with extras, they’re actually not too extensive or vital. There are just two songs performed by Fahey, though those clips are okay. The extended extract from the Pete Townshend interview holds some interest, but — not too surprisingly — Townshend often talks more about himself than Fahey, sometimes in a way that strays from the question or the documentary’s actual subject.