Ever since rock started top songwriters, whether soloists or in bands, have had some of their compositions covered by other artists without releasing their own versions. Sometimes the same guy or guys have covered more than one such surplus tune, as Billy J. Kramer, the Fourmost, and Peter & Gordon did with Lennon-McCartney songs the Beatles didn’t release while they were active. But it’s rare that an artist covers half a dozen such extras at once, none of which had been released by anyone.

The 1970 self-titled album by Yellow Hand might be the most extreme example of an act giving so much of a rock LP over to such items between the mid-‘60s and early 1970s. The group covered no less than half a dozen Buffalo Springfield outtakes that had never been issued by the Springfield or anyone else. Among them were two Neil Young songs (“Down to the Wire” and “Sell Out”) and four Stephen Stills compositions (“Come On,” “Hello I’ve Returned,” “Neighbor Don’t You Worry,” and “We’ll See”). These weren’t even accompanied by other songs by the same writers that had been released.

Although a Buffalo Springfield version of “Down to the Wire” came out on Young’s 1977 triple-LP Decade retrospective, Springfield versions of the other five didn’t come out until the twenty-first century (though most of them circulated on bootlegs). Basically, Yellow Hand got access to the outtakes because Buffalo Springfield’s original manager/producers, Charlie Greene and Brian Stone, had the publishing on the songs and wanted to make a little money off of them.

I told the whole story of Yellow Hand—based on recent interviews with the group’s guitarist, Pat Flynn, and their singer, Jerry Tawney—in a lengthy (nine-page) feature in the spring 2021 (#56) issue of Ugly Things magazine. Then a teenage guitarist, Flynn was actually given a literal shoebox of cassettes of Buffalo Springfield demos to learn the songs, the band Yellow Hand subsequently forming and recording their LP for Capitol.

Are there any other examples of, as my unwieldy headline for this post reads, “Multiple Covers of Unreleased Songs by Major Acts on the Same Album, From the Mid-’60s to the Early ’70s?” None that are as extreme, but here are a half dozen albums that made the most of someone else’s vaults:

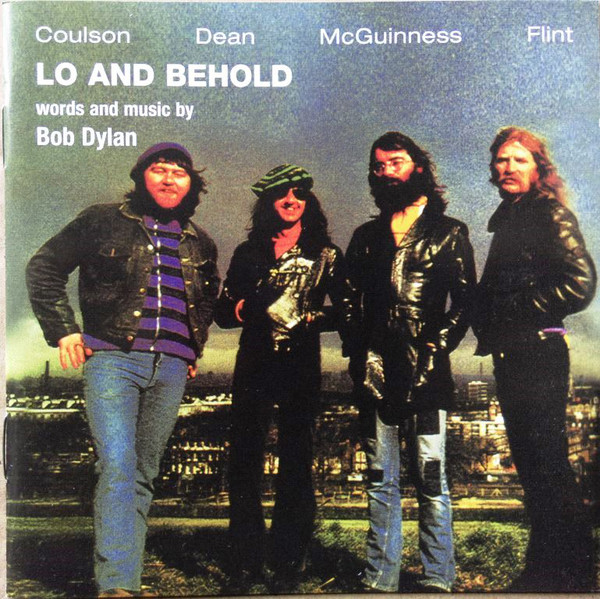

1. Coulson Dean McGuinness Flint, Lo and Behold. McGuinness Flint, featuring ex-Manfred Mann bassist/guitarist Tom McGuinness and ex-Bluesbreakers drummer Hughie Flint, had a couple big UK hits in the early ‘70s without making much headway in the US. Teaming up with Dennis Coulson and Dixie Dean, their 1972 album Lo and Behold was devoted entirely to interpretations of then-obscure Bob Dylan compositions. None of the ten songs had appeared on official Dylan records, though his versions have subsequently appeared on archival releases.

At a glance that seems to outdo Yellow Hand, but not all of the ten tunes were previously unissued by anyone. The Byrds, for instance, put “Lay Down Your Weary Tune” on their second album, and Jim & Jean put out their version soon afterward. Happy Traum had done “Let Me Die in My Footsteps” back in 1963 as “I Will Not Go Under the Ground.” John Walker, Thunderclap Newman, and others had done “Open the Door, Homer.”

One of Dylan’s own versions of “The Death of Emmett Till,” though recorded in the early 1960s, came out on a Folkways compilation in 1972 credited to the pseudonym Blind Boy Grunt, though it’s difficult to tell whether that LP appeared before Lo and Behold. So points off for mixing in songs that had already been available, if you keep tabs on that sort of thing.

As Tom McGuinness told me in his interview for Ugly Things #49, “I was lucky because I got a lot of the acetates from the time of the Band. Because Albert Grossman came to London with the Basement Tapes and played them to Manfred Mann, the whole group. So I had all these Dylan acetates lying around. Then McGuinness Flint, we were published by Feldman’s, who were Dylan’s publishers in the UK at that point. A guy up there gave me like fifty cassettes of Dylan demos. So I just had this idea of doing some of the little known Dylan songs that were on these cassettes. It’s one of my favorite things I’ve ever done in my life.”

2. Hamilton Camp, Paths of Victory. Playing the Dylan card much earlier than Coulson etc., Camp’s Paths of Victory, issued around late 1964, had seven songs by the man. No less than six of them had yet to appear on Dylan’s own albums, though “Girl from the North Country” had been on Dylan’s second LP, and Bob had done “Only a Hobo” under his Blind Boy Grunt alias for the 1963 compilation Broadside Ballads Vol. 1. Again, Dylan’s own versions of the other five of his compositions here have all come out on archival releases.

Of those other five, “Walkin’ Down the Line” had been on Jackie DeShannon’s self-titled 1963 album, and “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” on a 1963 LP by Ian & Sylvia. Release dates have been variably reported for early-to-mid-‘60s folk LPs, but Camp seems to have beaten Odetta to the punch with “Long Time Gone” and “Paths of Victory,” which appeared on Odetta Sings Dylan, probably issued in early 1965. That left just one of what we might call an “exclusive,” as “Guess I’m Doin’ Fine” doesn’t seem to have been covered by anyone else.

Camp was an interesting figure who already had a solid reputation in the folk world for his recordings (under the name Bob Camp) as a duo with a bigger name from the early folk revival, Bob Gibson. He also wrote “Pride of Man,” his original version highlighting this LP, a few years before Quicksilver Messenger Service did a great rock cover. But this is a folk album, not a rock one. And while he deserves points for scouring for half a dozen of Dylan’s more obscure tunes at a point before Bob was quite as iconic as he’d be in a year or so, not all of them had been previously unissued by anyone.

As for how Paths of Victory got so Dylan-heavy, Camp told me in an interview nearly twenty years ago, “Dylan was hot, so [Elektra Records chief] Jac [Holzman] thought it was very smart to put more Dylan tunes on there, much to my regret. I originally had done a kind of very eclectic collection. I don’t think any tunes [that didn’t make the final LP] were original, but there were different interpretations of a lot of kinds [of] folk songs, [like] ‘Railroad Bill.’ I liked the album that way.

“But he didn’t like that. He said he wanted more Dylan tunes. So they sent me a tape out of Dylan’s, it was reel-to-reel. I learned three or four tunes, and slapped them on, much to my regret. Because I really got hit for it, in especially the Minnesota folk scene. A magazine called The Little Sandy Review that came out of Minneapolis — it was all Dylan cronies — they just hated it!”

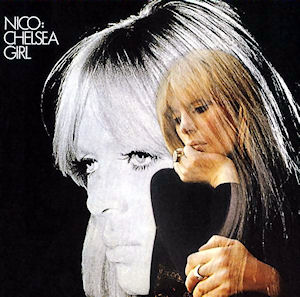

3. Nico, Chelsea Girl. An underrated baroque-folk production, Nico’s first album, released around the beginning of fall 1967, showcased obscure or wholly unreleased songs by a wealth of fine songwriters. Among them were Jackson Browne, Bob Dylan, Tim Hardin, and no less than five tracks—half the LP—of compositions by fellow Velvet Undergrounders Lou Reed and/or John Cale (with Sterling Morrison getting a co-credit on one and Nico herself on another).

All of these were fine and generally folkier than most of The Velvet Underground & Nico, on which Nico had of course sung a few classics. A few were really fine, namely the epic “Chelsea Girls” and the haunting “It Was a Pleasure Then,” which is a Velvet Underground recording in all but name, as Nico’s backed by Reed and Cale. None had been previously released by anyone, though a 1965 VU demo of “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams” would appear on a 1995 box set.

But this is in a way more a Velvet Underground spin-off album than a record by an artist who digs up a batch of otherwise unrecorded songs by an unrelated major act. Nico had sung with the Velvet Underground, albeit only on a few tracks; Reed, Cale, and Morrison all played on the Chelsea Girl sessions, though it can’t be pinpointed what they did on each cut. This doesn’t take anything away from the LP’s considerable status. But it isn’t quite as, to use the word again, “extreme” as Yellow Hand’s Buffalo Springfield homage.

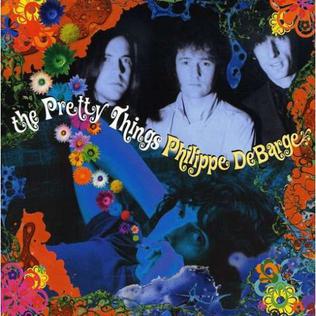

4. The Pretty Things, Philippe DeBarge. Any excuse to put the Pretty Things in as many places in Ugly Things as possible, right? But seriously, this 1969 album was seriously teeming with previously unheard Pretties originals. True, three of them (“Alexander,” “Eagle’s Son,” and “It’ll Never Be Me”) had been done by the band without credit on the Even More Electric Banana album, and one (“Send You With Loving”) for a May 1969 BBC session. But not many people knew about that then, and frankly not many do now, especially if you don’t count Ugly Things readers. Otherwise this is pretty fair psychedelic pop that got an even smaller audience than Even More Electric Banana, since it didn’t get released back then.

And what’s it doing here, if it’s a Pretty Things album with Pretty Things songs? The story’s been told by Ugly Things editor/publisher Mike Stax in his magazine and the liner notes to UT’s CD of the recordings, but basically this was a Pretty Things album with a singer who wasn’t in the band. French fan Philippe DeBarge took the lead vocals, though usual Pretties vocalist Phil May co-wrote all of the songs.

May was diffident about the project when I interviewed him in 1999. “Wally [Waller] and I just wrote a bunch of songs for this French millionaire,” he told me. “No kind of falseness about, ‘He was a musician.’ He just wanted to make a record with the Pretty Things, and he was prepared to pay.”

Added May in Mike Stax’s liner notes for the Philippe DeBarge CD, “I don’t think any of us had great expectations, but we didn’t approach it in that way. We approached it like it was another record to make, and we were getting stuff out of it for ourselves, apart from the finances. It was a good stepping stone between S.F. Sorrow and Parachute.”

In the same notes, Waller also acknowledged the sessions had some value. “For me it was a chance to be the boss in the studio for the first time. I had always been really involved with the production process on all our albums. And I just loved to have the chance to write a few songs and see them through to the end. I think the project put us in a much better shape to tackle something like Parachute.”

As for DeBarge, speculated Wally, “Quite what he was going to do with it I don’t know. I don’t think there would have been any interest from the British music industry, and being in English it wasn’t really suitable for the French market. I think it was a grand indulgence on Philippe’s part. To be honest I was not surprised that nothing became of it.”

This is certainly a worthy adjunct to the Pretty Things discography, and as dedicated to otherwise unavailable songs by a major artist as anything here. But while it’s not quite a Pretty Things album, it’s a Pretty Things album in all but name, with even the guy (May) who didn’t take his usual position playing a major role as writer and backing singer. So it can’t quite be considered a record with “covers” of someone else’s songs, as interesting as it is.

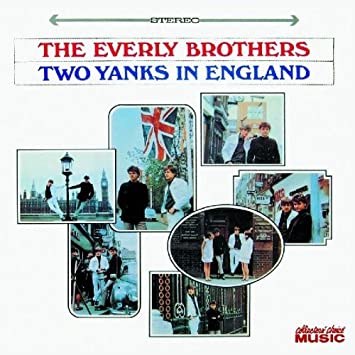

5. The Everly Brothers, Two Yanks in England. Recorded in 1966, this decent LP looked a little like a Hollies tribute at a glance. Eight of the twelve songs were written by the Hollies, credited to the “L. Ransford” pseudonym for Allan Clarke, Tony Hicks, and Graham Nash. The Hollies also played on the sessions, and none of the songs the Everlys covered were well known.

While you had to be (and still have to be) a pretty big Hollies fan to know it, five of these eight songs had already been released on the group’s LPs and B-sides. Three of them would come out on Hollies releases over the next couple years, though you had to be a damned dedicated follower to know that “Like Every Time Before” surfaced on a 1968 B-side in Germany and Sweden.

So – good though not great concept, good though not great results, yet not teeming with previously unheard numbers by their benefactors. The last album on this list has even less such material, though it could have had more.

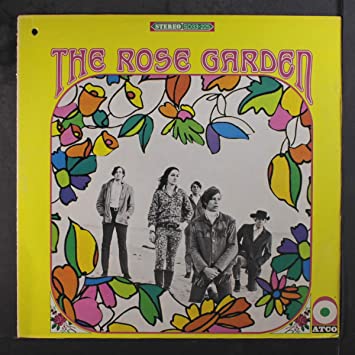

6. The Rose Garden, The Rose Garden. Like Yellow Hand, the Rose Garden had just one self-titled LP, though they’re far better known as they had a #17 hit at the end of 1967 with “Next Plane to London.” Even people familiar with the single usually didn’t hear their album, which meant that few realized ex-Byrd Gene Clark wrote a couple songs on the disc that hadn’t appeared anywhere else. The young band had developed a friendship with Clark, who offered them “Till Today” and “Long Time.” Both songs found a place on the LP, which had little original material by the group.

Two songs isn’t that much, and there are other examples of acts getting first crack at a couple tracks at once, like Silver Metre did with some Elton John-Bernie Taupin efforts on their 1969 self-titled album, and Jim & Jean did with a pair by their friend Phil Ochs on 1966’s Changes, before Ochs put out his own versions. What puts The Rose Garden over the top in this specialist competition is that they actually could have done more Gene Clark exclusives. Clark gave Rose Garden guitarist John Noreen a five-song acetate of songs to choose, but the band took only “Long Time” from that batch. They also recorded an unreleased version of Neil Young’s “Down to the Wire,” and passed on a few other songs by Young and Stephen Stills that were offered to them by Greene and Stone, including “Come On.”

So The Rose Garden could have been half-full of previously unheard Gene Clark songs – but wasn’t. (For that matter, it could have been half-full of previously unheard Clark compositions and half-full of previously unheard Buffalo Springfield leftovers.) If you’re fretting that those other Clark songs on the acetate are lost forever, fear not. The entire acetate (including Clark’s version of “A Long Time”) was issued in 2018 as bonus tracks to the CD reissue of a different eight-song acetate Gene cut in 1967, Sings for You.