It’s not a good time for everything—just listen to a presidential debate if you want a taste of what’s wrong with the world—but it’s a good time for rock history books. Maybe it’s a combination of more and more veteran rockers wanting to get their stories down while there’s still time, as well as the book market making room for more and more “niche” titles, now that many of the stories of bigger stars and styles have been told. But we’re still seeing lots of memoirs of musicians famous and obscure, along with biographies and less easily classified volumes that go down roads dismissed as of little interest to anyone just a few years ago. Even some of the books on superstars shed new light on their subjects, along with the inevitable recycling of lots of material that’s already familiar to knowledgeable fans.

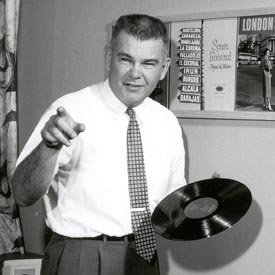

My selection for #1 rock history book of 2015.

Such are the wealth of choices, in fact, that it’s pretty hard to make annual “best-of” lists without missing a few contenders that you aren’t able to read (or aren’t even aware of) before the end of December. So this post is divided into a couple sections. One is my list of best rock books of 2015, for which only books published between January 1 and December 31 were considered. And as this post was finished only a day or two before the end of December, it does consider all books I read in the calendar year, unlike many best-of lists that are submitted to publications a month or two (or even three) before the year actually ends.

But since it does take a while to both find out about and catch up on books from the last year or two, this post also lists noteworthy 2014 titles that didn’t make my actual 2014 Top Twenty or so list. It’s always frustrated me, as a writer and reader (and listener), that many print publications consider books and records yesterday’s news after just a few months. Books from 2014 really aren’t that old, and – like music from before 2015, or any art regardless of its age – could and should be enjoyed at any time. These 2014 books do have the advantage over, say, 2004 books (let alone 1964 books) of still being easily available, even if you might not see them mentioned in upcoming review sections, or even year-end roundups. As for the 2015 books I haven’t yet been able to read, well, I’ll be able to mention some of them as a supplement to my 2016 list.

I’ll start with my Top Twenty books of 2015. I have much longer reviews of the ones relating to Sandy Denny, Ray Davies, and Merrell Fankhauser in issue #7 of Flashback, the London-based ‘60s/’70s rock history magazine.

1. I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn: The Biography of Sandy Denny, by Mick Houghton (Faber & Faber). A major work, this 500-page biography doesn’t exactly make the only other significant book on Sandy Denny (No More Sad Refrains: The Life and Times of Sandy Denny, by Clinton Heylin) redundant. But this excellent volume is certainly better, and will certainly stand as the definitive account of her life, drawing on first-hand interviews with more than fifty of her surviving colleagues, family, and friends. Houghton was also granted access to the entire archive of Denny and her husband (and, in Fotheringay and a later version of Fairport Convention, bandmate) Trevor Lucas, including previously unresearched documents and photos. The wealth of material is tied together with an even hand that both praises and criticizes her music when warranted. Also included is a lengthy “playlist” section that places her recordings in useful context with releases by other artists (usually folk-rockers) who moved in the same circles as Denny, or had some influence on her.

Note that the race, if you want to call it that, between this and the #2 pick below (Ray Davies: A Complicated Life) for the #1 position was so close that the rankings could have easily been reversed, or declared a tie. I went with the Denny bio as she’s been covered a lot less than Davies and the Kinks, making it ultimately of very slighter significance and value.

2. Ray Davies: A Complicated Life, by Johnny Rogan (The Bodley Head). Although this is titled like it’s a biography of the Kinks’ main singer and songwriter, Ray Davies, it’s more like a book about the Kinks themselves. And it’s a very long and thorough one, too, running about 750 pages, including loads of first-hand and off-the-beaten-track interview material with the Kinks and close associates. Note that although Rogan wrote a previous Kinks biography that draws from many of the same interviews, there’s a lot more information here, including some re-interviews of subjects he spoke to the first time around. And while it does cover Ray Davies’s life to the present, the great bulk of it—well over half—is devoted to the Kinks’ prime decade, from the early 1960s to the early 1970s.

Another crucial plus is that Rogan interviewed many central and auxiliary figures, including all of the Kinks worth noting (though not much is used from drummer Mick Avory) and crucial associates like producer Shel Talmy and early managers Robert Wace and Larry Page. For this edition (if you look at it as a three-times-the-size expansion of his 1980s Kinks book), he tracked down some notable characters who’ve seldom or never spoken on the record, like pre-Avory drummers John Start and Mickey Willett, and Ray’s first wife Rasa, who sang on many of the Kinks’ ‘60s tracks. Although some of Rogan’s angles might get on the wrong side of some fans (particularly his frequent citations of Ray’s miserliness), it’s woven together with an expertise and readability that will make most of it a page-turner for Kinks devotees. In addition to his own research, the author also excerpts from a wide source of articles stretching back fifty years, as well as some unedited film footage, transcripts, and notes from interviews conducted by others.

3. Notes from the Velvet Underground: The Life of Lou Reed, by Howard Sounes (Doubleday). Besides being the principal genius behind the Velvet Underground (and the creator of some good subsequent music during his long and erratic solo career), Lou Reed was notorious for being a difficult, cranky man who alienated many colleagues, romantic partners, and journalists. This well-researched, cogent biography won’t change that perception. But it’s backed up by first-hand interviews with many (though certainly not all) people who knew and worked with him throughout his life, including members of the Velvet Underground, producers, musicians in his bands, record label executives, and managers. Of special interest are comments on his married and family life by relatives and partners who have not often spoken on the record, particularly his first wife, Betty Kronstad, and his sister Bunny.

In line with many rock bios, the music Reed made got less interesting toward the end of his life, and Sounes thins out the coverage of his less essential efforts in appropriate fashion. The Velvet Underground years and his early solo work gets the most attention, and while the author doesn’t shy from criticizing Reed’s weakest records and songs, he also gives proper kudos to Lou’s best. While much of this ground will be familiar to Reed enthusiasts, it’s a better book than the previous major volume on the singer, Victor Bockris’s Lou Reed: The Biography. Sounes is considerably more accurate, did more legwork, and presents his opinions in a much more reasoned fashion.

Incidentally, another Reed biography, Aidan Levy’s Dirty Blvd.: The Life and Music of Lou Reed, appeared near the end of 2015. While I did not find it strong enough to include on my list, it does have some interesting stories from people who haven’t been interviewed much—including some people interviewed for Notes from the Velvet Underground (like Betty Kronstad) and some not (like Vinny LaPorta of the Tots, who backed Reed in concert for a while in the early 1970s). I’ve read reports that no less than three other Reed biographies are on the way, and while more info on Lou is always welcome, you have to wonder how those are going to avoid overlapping with what’s already out there.

4. Allen Klein: The Man Who Bailed Out the Beatles, Made the Stones, and Transformed Rock & Roll, by Fred Goodman (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). As business manager of both the Rolling Stones and the Beatles in the late 1960s and early 1970s (as well as numerous other British rock acts), Allen Klein played a controversial role in their careers. Although he gained unprecedented concessions from record companies for his artists, he also sowed some discord within the Beatles and Rolling Stones through both his personal style and his financial practices. The legalities of his contractual relationships with his clients aren’t all that easy to wade through if you don’t have a head for that sort of thing. But this book lays them out for the layperson with about as much accessibility as can be attained, combining the business analysis with plenty of stories about the colorful manager’s abrasive style and relationships with the celebrated rockers he represented.

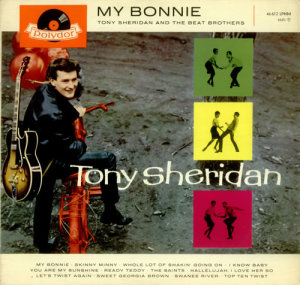

5. Shake It Up Baby! Notes from a Pop Music Reporter 1961-1972, by Norman Jopling (RockHistory). Jopling was a reporter for several UK music papers between the early 1960s and the early 1970s, most notably for Record Mirror, where he worked the bulk of that time. He’s most famous for writing the first piece about the Rolling Stones to appear in a national music paper (Record Mirror in spring 1963, before they had a record deal), but wrote about almost all sorts of rock and soul. His 500-page memoir is a very entertaining look not just inside the British music press, but the explosive growth of rock (particularly British rock) itself during that period, Joplin having written about and interviewed many legends from the Beatles on down. Some readers might find the frequent inserts of passages reprinting some of his old (usually brief) Record Mirror features distracting, but on the other hand, those articles are themselves of interest (and give a flavor for the era), and not easy to find elsewhere. Also of interest are his memories of an ill-fated attempt to start an independent record production company in the late 1960s with one-time early Who manager Pete Meaden.

6. Good Night and Good Riddance: How Thirty-Five Years of John Peel Helped to Shape Modern Life, by David Cavanagh (Faber & Faber). From 1967 until his death in 2003, John Peel was the most influential DJ in the UK, at least as measured by how many up-and-coming acts of all kinds and eras he helped expose to a national audience. This quite large (620-page) book is not so much a biography as a survey of 300 radio broadcasts he presented, including a few he did on the pirate station Radio London in 1967 before joining the BBC. Woven into the program descriptions are details about both Peel’s personal life and the rapidly changing music scene in general.

I had my doubts about whether this format could work, but Cavanagh does an excellent job of balancing the different facets of what he covers. It’s neither an encyclopedic reference of what Peel played when or an account of his life (which Peel gave, rather unsatisfactorily, in the autobiography Margrave of the Marshes). Instead, it’s a highly readable volume that incorporates plenty of colorful anecdotes from his eccentric life, as well as documenting his eclectic tastes and avaricious hunger for new music. That made him an unlikely icon of both the psychedelic/progressive era and the punk/new wave one, though his enthusiasm for the brand-new could be reckless and dismissive of music that wasn’t up-to-the-moment, even music that he’d championed not too many years before he moved on to other styles. It also functions almost as a reflection of the many changes rock (particularly the underground variety)—and, to some extent, folk, world music, and hip-hop—went through between 1967 and 2003, Peel remaining keen all the while to find the new and the novel, even though his extreme ranges of taste guaranteed that no listener would enjoy everything he played.

7. Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock’n’Roll, by Peter Guralnick (Little, Brown). Huge (about 750-page) biography about the man who founded and ran Sun Records, the label that’s most famous for launching Elvis Presley in 1954 and 1955. Sun also did the first, or some of the first, recordings by rockabilly stars Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Roy Orbison, as well as bluesmen B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, Ike Turner, and Junior Parker, along with many others. Guralnick interviewed Phillips many times over a period of more than twenty years, and also spoke with many of his artists, colleagues, and family (not to mention several women with whom Phillips had lengthy affairs). He also had access to quite a few letters, and rare photos and documents, some of which are reproduced in the book.

Nonetheless, I expected this to rank higher on my list than it does. As someone who holds Guralnick in esteem for the wealth of important writing he’s done on American roots music since the ‘70s; who greatly enjoys huge books whose length seems to put the general reader off; and has written huge books myself, it pains me to write the following cautionary. But it has to be said that while the story’s told in great detail, the detail is perhaps too great, as it really could have done with some editing to make the story more readable and less jammed with superfluous stories and repetitious over-effusiveness. To a greater extent, these flaws diminished his Sam Cooke biography; it has not been such a factor in my favorite Guralnick books, such as Sweet Soul Music and his two-part Elvis biography. If it’s the gist of the Sun story you’re after, you don’t miss too much if you go for Colin Escott and Martin Hawkins’s excellent, more concise Good Rockin’ Tonight: Sun Records and the Birth of Rock and Roll.

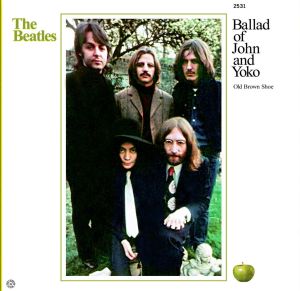

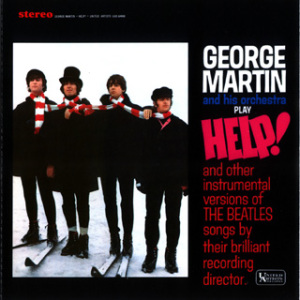

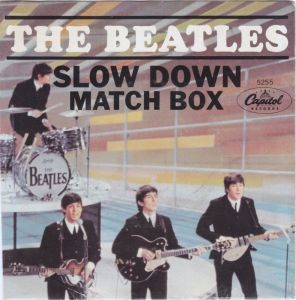

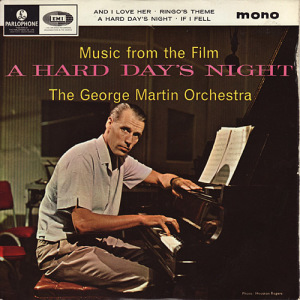

8. Beatles Gear: All the Fab Four’s Instruments from Stage to Studio: The Ultimate Edition, by Andy Babiuk (Backbeat). Beatles Gear has been a great reference since its original publication in 2001 (with a revised edition appearing the following year). Almost fifteen years later, we have “The Ultimate Edition.” Unlike many books bearing such tags, it really is a major expansion of the original volume, doubling in size to 512 coffee table-sized pages. The extra material comes chiefly in the form of more than 650 (!) additional photos, though there’s some new information in the text as well, often from people with inside stories about the Beatles’ instruments who contacted Babiuk after the first edition.

Of most importance, however, is that this remains one of the core Beatles books for those who want really detailed, intensely researched stories on how, why, and where the group played their many instruments. It covers not just their guitars, bass, and drums, but also the keyboards, harmonicas, sitars, amps, etc. they also used, all the way up to their deployment of the Moog on Abbey Road. It’s true that gearheads will get the most out of this, but you don’t have to be a musician to enjoy the text. It’s presented in a highly readable fashion, with the technical nitty-grittys usually shuttled into paragraphs that can be skimmed if you don’t need to know where all the knobs were. The photos are highly entertaining and of themselves, with lots of pictures of the Beatles’ instruments; repros of vintage instrument ads; memorabilia like receipts for the purchase of their instruments; and plenty of pix of the group themselves onstage and in the studio, a few of which have never before been published.

9. Sound Explosion: Inside L.A.’s Studio Factory with the Wrecking Crew, by Ken Sharp (Wrecking Crew LLC). As kind of a companion to the well-received documentary The Wrecking Crew! (see best-of-2015 music documentary listings), this paperback coffee table book is an oral history of the Los Angeles studio musicians who played on countless 1960s rock records. There are quotes, sometimes numerous and extensive ones, from many of the most notable session musicians from the scene, like Carol Kaye, Tommy Tedesco, Don Randi, Larry Knechtel, and Hal Blaine. There are also many quotes from artists who used those musicians and producers, including big names like Brian Wilson (and other Beach Boys) and Phil Spector. And there are many cool period photos, some in color, as well as rare graphics and documents from the time, including some session sheets (which tell you exactly who was on the Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man” session, for example). There’s some redundancy between quotes in the main section of memories, as well as some harsh assessments of the bands they were ghosting for (and indeed of rock’n’roll in general), giving the impression some of the players felt the whole music was beneath them. But their memories are overall worthwhile, and complemented well by a final section with detailed stories about several dozen 1962-70 hits on which the Wrecking Crew participated.

10. Blood, Sweat and My Rock’n’Roll Years, by Steve Katz (Rowman & Littlefield). Guitarist, harmonica player, and singer-songwriter Steve Katz was an important part of the Blues Project and Blood, Sweat & Tears. He was also in some lesser known if interesting groups (the Even Dozen Jug Band and American Flyer), and did some producing, most notably for Lou Reed in the mid-1970s. This is a straightforward recount of his experiences, focusing mostly on the 1960s and 1970s, and more on the Blues Project and early BS&T than anything else. Which is appropriate—unlike some other memoirs by veterans from the period, it’s not padded with extraneous material, cutting mostly to the bone of the music and craziness of the era’s music business.

With understated wit, Katz fills in a lot of detail about the dynamics of his bands, and has some pretty harsh things to say about his older brother (and, for a while, Lou Reed manager) Dennis, Blues Project/original BS&T keyboardist Al Kooper, and BS&T lead singer David Clayton-Thomas. (For another view of disputes between Kooper and Katz, there are missives from the other side in Kooper’s memoir, Backstage Passes & Backstabbing Bastards.) If you’re wondering whether Reed comes off better here than he does in Howard Sounes’s Notes from the Velvet Underground: The Life of Lou Reed (see review earlier in this post), no, he doesn’t. Even as a fan of the Blues Project and first-album BS&T, there are a good number of stories that were unfamiliar to me, like Katz’s affair with Mimi Fariña, the brief presence of Emmaretta Marks in a Blues Project lineup, and BS&T’s tour behind the Iron Curtain. Most affecting was his summary of the Blues Project’s legacy—“a great live band who, thanks to an uncaring record company, made some pretty poor-sounding records that never further than FM radio.”

11. Nico: In the Shadow of the Moon Goddess, by Lutz Graf-Ulbrich (self-published ebook). In the last half of the 1970s, Graf-Ulbrich (then known simply as Lutz Ulbrich) was Nico’s off-on guitarist and boyfriend. This slim but illuminating English-language memoir concentrates on the years he toured with her, also adding a bit about his interactions with the singer before (when he was guitarist in the Krautrock bands Agitation Free and Ash Ra Tempel) and after that time. It’s enlivened by some rare photos, posters, and documents, as well as letters and postcards (in German, with English translations supplied) she wrote him during their relationship. Ebooks are making niche-within-niche books like these more viable, and more are likely on the way from all directions that fill in the cracks of cult rock history.

12. Psychedelic Bubble Gum: Boyce & Hart, The Monkees, and Turning Mayhem into Miracles, by Bobby Hart with Glenn Ballantyne (SelectBooks). As half of the songwriting/performing duo Boyce & Hart, and supplier of material for the Monkees and the Partridge Family, Bobby Hart was about as mainstream a figure in 1960s mainstream pop-rock as there was. So he won’t win any awards for hipness from many critics, but his nearly decade-long journey from journeyman singer to hit songwriter (both for the Monkees and Boyce & Hart) was pretty interesting. There’s nothing too earth-shaking about this memoir—it’s just a solid, straightforward account of his career, emphasizing the decade from his arrival in Hollywood in the late 1950s to his late-‘60s peak. There are plenty of stories about the more behind-the-scenes aspects of the era’s recording industry, from printing shops that generated the physical record labels on discs to the demo studios, Brill Building offices, and Hollywood lots where Hart (usually with Tommy Boyce) got much of their work and hustling done.

As prototypical as their career path was in many ways (though it reached a far higher zenith of success than most aspiring songwriting teams), there’s also the occasional surprise, like finding out Boyce’s girlfriend was stolen from him by New York record magnate George Goldner, or that Micky Dolenz’s wordless scatting in “Last Train to Clarksville” came about because he had trouble jamming in all the words of the original bridge. Hart was in some ways hipper than his music, as Boyce & Hart were active in campaigning to lower the US voting age from 21 to 18 and supported Robert F. Kennedy’s campaign. He also got heavily into spiritual matters from the 1970s onward, and one gets the feeling he would have been happy to write a lot more about that journey, though it’s largely limited to the final pages of this autobiography. Which is typical of the humility of his prose, which largely sticks to the story without making grander claims for himself than are merited.

13. How Can It Be? A Rock & Roll Diary, by Ronnie Wood (Genesis Publications). Page-by-page reproduction of Ronnie Wood’s 1965 diary, when he was lead guitarist in struggling London R&B/rock band the Birds (who had a few singles, but no hits). Although this is for pretty serious Wood/Rolling Stones fans, if you are one, it’s a fascinating “he was there” look at the London R&B/club circuit. That’s not so much for the diary entries, which are mundane details about their gigs and friends, but for the memories and observations about the time they spark in the many comments Wood wrote especially for this reproduction. It’s a real-time document of a different era, when a reasonably talented but ultimately also-ran band—one of many playing in the style of the Rolling Stones that sprang up after the Stones’ initial success—could regularly run into other legends on the scene like the Who, as well as many also-rans, like the Artwoods (with Ron’s brother Art on vocals). It’s also enhanced by numerous photos and reproductions of gig posters from the time.

It’s also a reminder of the underside of the scene in which daily life was not dominated by the hit records and headlines enjoyed by the Stones and Who, but exulting over a record getting into the Top Sixty (and panicking when it quickly fell out); getting a royalty check of 15 pounds or so; being unable to rehearse in the inept harmonica player’s big garage after kicking him out of the band; backing Bo Diddley on tour; and having your mother remember Keith Moon as a gentleman, not a crazed loon. And, in a publicity stunt cooked up by their manager, serving the Byrds (from the US, with a y) writs for using a similar name when they arrived at the airport for a British tour—an incident Wood expresses guilt for, though he does note it finally got them on the front page of Melody Maker. There are also occasional brief stories about Ron’s post-1965 career, like his memory of how he got into the Jeff Beck Group by simply calling him up after Beck left the Yardbirds and asking what he was up to. Note that while this first came out as one of the very expensive limited editions in which Genesis specializes, it very quickly also came out in an affordable mass-market hardback edition close to the standard list price that you might expect from a book like this.

14. Electric Shock: From the Gramophone to the iPhone: 125 Years of Pop Music, by Peter Doggett (The Bodley Head). Well, veteran rock and country historian Doggett didn’t set his sights low with this 630-page volume (710 counting index and source notes). This is quite possibly the most wide-ranging history of popular music—not just rock, but all forms of pop, roughly from the time records started to be made—ever written. Having the widest breadth, of course, does not equate to the deepest depth, and much of the territory might be familiar to readers schooled in one or more of the eras or styles discussed, from ragtime and swing to all forms of rock, reggae, hip-hop, and (at the very end) twenty-first-century electronic dance music.

The book’s greatest value is not in its hard information, but in examining the interrelationships between these styles; how many trends (particularly the absorption of African-American styles into the mainstream and Establishment condemnations of new, exciting genres as the end of civilization) have repeated themselves over and over since the 1890s; and, more than any other book of which I’m aware, how technology has done much to shape popular music, from wax cylinders through 45s, LPs, cassettes, CDs, and the current online mediums of Spotify, youtube, and iTunes. Inevitably, there are some gaps; American and British music is heavily accented, and there’s little attention given to some styles, like jazz-rock fusion, the late-‘60s British blues boom, and the outlaw country movement. On the other hand, there are surprisingly numerous sections on movements relatively little known to the English-speaking mainstream, like French yé-yé music and Brazilian tropicalia. No matter how encyclopedic your knowledge of pop through the ages, there will almost certainly be styles discussed of which you’re only dimly aware, with all sorts of nuggets of intriguing trivia and obscure factoids sprinkled throughout the text.

15. These Are the Voyages: TOS [The Original Series]: Star Trek Season One/Two/Three, by Marc Cushman with Susan Osborn (Jacobs/Brown, 2013/2014/2015). As I wrote when I listed this in a previous post about expensive/rare rock books, some readers will think this is an outrageous inclusion, and they have a point, since this is about Star Trek, not about rock music. What’s more, it’s not exactly a 2015 book, but a three-volume series, the third and last of which did happen to come out in 2015.

Still, there seems to be enough of a crossover between rock fans (especially of ‘60s rock) and Star Trek to make this three-volume set worthy of attention in a post like this, especially since they’re the kind of specialist books that haven’t gotten a lot of press outside of the Trekkie community. This is an astonishingly detailed episode-by-episode survey of all 79 programs from the original series, drawing on lots of first-hand interviews, photos, and production notes. In that sense, it’s kind of an equivalent to a rock book like Mark Lewisohn’s The Beatles Recording Sessions, giving even experts their first real play-by-play look at what happened behind the scenes. As the three volumes add up to a total of 2000 (!) pages, it’s not for the casual reader, or even the casual Trekkie. But while undeniably long, this three-volume series isn’t all that expensive, especially if you get all three at once—which you can do for $67.95 plus shipping through the thesearethevoyagesbooks.com website.

16. Dreams to Remember: Otis Redding, Stax Records, and the Transformation of Southern Soul , by Mark Ribowsky (Liveright). The title’s a little over-wordy and misleading: this is an Otis Redding biography, not something that focuses on his milieu rather than his life. It’s better than the only previous one of substance that I’m aware of (Scott Freeman’s Otis! The Otis Redding Story), offering more depth, though the absence of first-hand interview material with some key figures due to their death or non-participation is keenly felt. Some of the stories the author dug up offer a darker side to Redding’s life than his generally cheerful, kindly image is associated with, though they’re hardly as numerous or controversial as ones that dotted the careers of the likes of Jerry Lee Lewis or Phil Spector. Much attention is paid to his music, recordings at Stax, songwriting, and performances. Unfortunately there are some minor but apparent factual errors when the text ventures into some of the general rock and soul history outside of Redding’s direct orbit.

17. The Record Store of the Mind, by Josh Rosenthal (Tompkins Square). Rosenthal runs the Tompkins Square label, which has reissued many way-obscure folk, rock, and other kinds of recordings from the twentieth century, as well as putting out contemporary albums. This isn’t exactly a memoir as much as a series of short pieces setting down his thoughts on various musical subjects that interest him, whether they’re profiles of obscure artists or quirky stories about record collecting and working in the record business (at both Tompkins Square and Sony; he worked at the latter for quite a few years). As he cheerfully acknowledges, like Tompkins Square product, this volume is a niche product of limited interest to the public, writing at one point, “The only thing more likely to get ignored than your label is your book.”

But collectors of niche product will enjoy some of these stories, though their interest will vary widely according to their tastes. The best parts are those on artists who are seldom covered even by cult standards, like singer-songwriter Ron Davies, the early-‘70s Raccoon Records roster, and folk singer Tia Blake. Memories of the gigs he attended and artists he helped promote at Sony are more like hanging out with a seasoned record industry vet and hearing war stories. My personal interest runs most to the little known folk and folk-rock artists and records he discusses, though his more idiosyncratic stories about growing up as a rock fan in Long Island, running a label, and navigating the rough waters of the entertainment industry have their strong points too. The book’s range is too wide and the presentation too anecdotal and specialized to find an identifiable “market,” but the same could be said of the Tompkins Square label. And if your tastes are eclectic enough to include a few Tompkins Square releases in your collection, they’ll likely be wide enough to encompass a book like this too.

18. Photograph, by Ringo Starr (Genesis). First published a couple years ago as a very expensive limited edition, this book was issued in fall 2015 in an affordable (though not exactly cheap, with a $50 list price) mass-market version. This 300-page coffee table volume features photographs of and by Ringo, almost all of them predating 1975. There’s a little – not much – commentary on the pictures by Ringo, going back to childhood snapshots and mementos. Like some of the other specialized coffee table books on the Beatles and their members, it’s kind of in the “extras” category. But there are some interesting and rare images here, particularly from his pre-Beatles days in the 1950s and early 1960s, though some of the photos he took of non-Beatles topics are of more interest to Ringo than us, to put it kindly.

Although the text is more aptly described as extended captions than revelatory commentary, his plain-spoken to-the-point observations are sometimes bluntly informative and entertaining. On his decision to leave a factory to turn professional drummer: “Everyone in my family was disappointed, because I was going to Riversdale Technical College and working as an apprentice, and I could have come out of that with a piece of paper that said I was an engineer. That would have been big news in our house, that anyone would have passed anything.” And on his first solo album: “Sentimental Journey wasn’t just songs that my mum liked; it’s what my stepdad and all my family sang at these parties. I made that record with George Martin after I left the Beatles, partly because I didn’t know what else to do.”

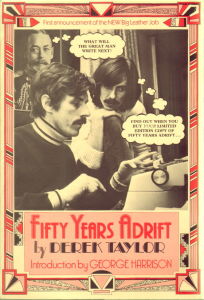

19. The Zapple Diaries: The Rise and Fall of the Last Beatles Label, by Barry Miles (Peter Owen Publishers). How do you make a 272-page book out of a label that issued just two records? To quote from one of Ringo’s big hits, “It Ain’t Easy.” But it’s a lot easier if you actually ran the label, as author Barry Miles did when he oversaw Zapple, the short-lived experimental subsidiary of Apple. It also helps if you’ve already written extensively about the Beatles in the 1960s and your personal interactions with them, as Miles has in several of his previous volumes. This might have rated higher had it not repurposed some material that appeared in his previous books In the Sixties and Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. But if you’re a Beatles fanatic as I am, it has its share of interesting stories—first-hand, not researched from several decades’ distance—of Apple, the last days of the Beatles, and unusual albums Miles did for Zapple with Richard Brautigan, Allen Ginsberg, Charles Bukowski, Ken Weaver of the FUgs, and others, though these weren’t actually released before Zapple went under, some of the material eventually appearing on other labels. There are quite a few interesting uncommon photos and reproductions of period documents too—another reason this was able to add up to 272 pages.

20. Folk City: New York and the American Folk Music Revival, by Stephen Petrus and Ronald D. Cohen (Oxford University Press, 2015). Straightforward and thorough, if slightly academic and dry, history of the folk revival as it took shape and flourished in New York from the 1930s through the 1960s. Produced in conjunction with an exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, this is highlighted by many rare and interesting photos and reproductions of posters and other memorabilia, which are the real reasons this ekes into the bottom of this list.

If you’re wondering why the following books weren’t mentioned, it’s because they came out in 2014. Honorable mentions, however, to these titles, which are also worthy of your attention. Indeed, some are so good that they would have been in or solid contenders for the 2014 Top Ten list:

1. Pretend You’re in a War: The Who & The Sixties, by Mark Blake (Aurum Press). Very in-depth and entertaining history of the Who through the beginning of 1970. This inevitably covers some of the same territory as a few of the other books on the Who, but does dig up some fresh first-hand information that sometimes questions or fills out myths that have surrounded the band.

2. Future Days: Krautrock and the Birth of a Revolutionary New Music, by David Stubbs (Melville House). A very thorough and well-written overview of “Krautrock,” the name that’s come to refer to German progressive rock of the 1970s. Drawing on interviews with numerous key musicians, it focuses on the major bands of the movement (Kraftwerk, Can, Amon Düül II, Popol Vuh, Faust, Tangerine Dream, Neu!), as well as covering some other notable acts and putting the whole genre in the context of changes in German society after World War II.

3. Gil Scott-Heron: Pieces of a Man, by Marcus Baram (St. Martin’s Press). Solid biography of a pioneer in mixing soul, jazz, and socially conscious poetry. Includes looks at his literary beginnings and his sad, long struggle with the kinds of drug addiction he examined in some of his songs, leading to stretches of homelessness, imprisonment, and little new music in the final quarter-century of his life. I found this far superior to Scott-Heron’s unfinished-feeling autobiography The Last Holiday: A Memoir (Canongate, 2013), which left a lot of unsatisfying gaps both in regards to what actually happened and how he felt about his life and work.

4. Clothes Clothes Clothes Music Music Music Boys Boys Boys, by Viv Albertine (Thomas Dunne). Critically acclaimed memoir by the guitarist of all-woman early London punk band the Slits might have gained wider attention than any of the Slits’ records. Unlike a lot of the 2014 books on this list, it did receive a good amount of coverage when it came out; it just took me a while to read a copy. And the praise was deserved, as it’s a page-turning account of growing into age in the punk era in London, not only discussing her time with the Slits, but also her interactions with other leading lights of the scene like one-time boyfriend Mick Jones. It does run out of a little steam after she retires from music for a long time in the early 1980s, but most of the book takes place before that.

5. Possibilities, by Herbie Hancock with Lisa Dickey (Viking). Straightforward, highly readable memoir by the jazz/funk crossover star covers his unlikely evolution from straightahead jazz pianist in the 1960s (as both a solo artist and member of Miles Davis’s band) to pop star when he went into jazz-rock-funk fusion in the 1970s and 1980s. Some readers might have wanted less about his drug use and religious beliefs, but those passages are both subordinate to the coverage of the music, and for the most part woven into his musical story as appropriate.

6. I’ll Take You There: Mavis Staples, The Staple Singers, and the March Up Freedom’s Highway, by Greg Kot (Scribner). Good straightforward biography of the Staple Singers, concentrating on their 1950s-1970s prime, when no other act made the transition from gospel to socially conscious soul and funk on a similar scale. Though one of their singers (Mavis Staples) is emphasized in the title, it’s more a book about the group as a whole, Staples giving the author by far the most interview material.

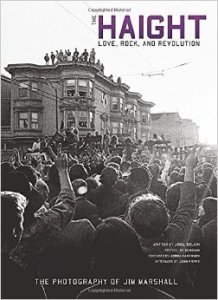

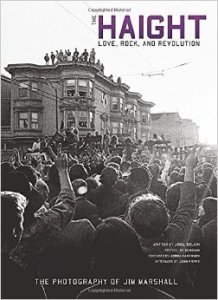

7. The Haight: Love, Rock, and Revolution: The Photography of Jim Marshall, by Joel Selvin (Insight Editions). 300-page coffee table book principally devoted to photos of the Haight-Ashbury and its affiliated rock/counterculture scenes in the 1960s, primarily in 1966 and 1967. While it has basic text about the Haight-Ashbury and San Francisco rock during the time by Selvin, it’s primarily a photo book spotlighting the work of top rock lensman Jim Marshall, with plenty of pictures of icons like Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, and Janis Joplin.

8. Brothas Be Yo, Like George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kinda Hard on You?, by George Clinton with Ben Greenman (Atria). Clinton came up with a book title that’s as hard to remember as many of his album titles. But this is actually a pretty straightforward memoir of the Parliament-Funkadelic man’s career. I’ve never found his records as interesting to listen to as descriptions of them usually lead me to anticipate, but most of this book is a quick-moving and interesting read, told in straight-up language that avoids sentimentality and droll humor that avoids cheap yuks. There are lots of stories about his strange career path from his New Jersey adolescence and young adulthood, where he spent as much time working at the barbershop as on his music, to the hard-to-define weird mixture of funk and rock he masterminded with P-Funk. There’s plenty of sex and drugs to go with the rock, but there are a lot of details about most of his records as well. The legal tangles he became immersed in over rights to his songs and recordings start to overwhelm the narrative in the final chapters, which start to make for slightly exhausting and depressing reading, though nothing on the order of the depressing exhaustion Clinton has undergone in his battles with the music business.

9. Calling from a Star: The Merrell Fankhauser Story, by Merrell Fankhauser (Gonzo Multimedia). Just the mere existence of a Merrell Fankhauser memoir would have seemed unlikely back in the twentieth century, when his cult was still spreading. Indeed, as much as that cult has spread, it’s a good bet that many of you reading this post don’t know who he is. His legend, such as it is, rests on his stints with three bands from the mid-‘60s through the mid-‘70s: Fapardokly, which made some beguiling if rather uneven folk-rock-psychedelia; his subsequent group H.M.S. Bounty, whose sole late-‘60s LP follows the same thread, but in a poppier direction; and MU, who in the early-1970s sounded something like a stoned fusion of Captain Beefheart and the Grateful Dead. This 200-page volume is a thorough, if sometimes rather matter-of-factly rendered, account of his improbable musical journey, from his early-‘60s surf recordings through steadily weirder enterprises (including some interactions and shared members with Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band) until 2013. The most interesting sections, as you’d expect, are on his stints with Fapardokly, H.M.S. Bounty, and MU, including some improbable stories that might be unfamiliar even to Fankhauser fans, like their Barry White-arranged session for Del-Fi Records; a brush with the Manson family; and a scheme to sell pot on Maui to build a recording studio for MU.

10. Big Shots: The Photography of Guy Webster, by Harvey Kubernik and Kenneth Kubernik (Insight Editions). Guy Webster photographed famous LP sleeves by the Rolling Stones (Aftermath, Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass), the Mamas & the Papas (their debut album), Simon & Garfunkel (Sounds of Silence), the Doors (their debut album), and Nico (The Marble Index), among others. This coffee table book doesn’t focus exclusively on those album sleeves, but the sections that do are the most interesting, featuring outtakes and stories behind the photo sessions. Also in the book are numerous ‘60s rock photos, as well as others from the era of non-musician celebrities like Jack Nicholson and Jane Fonda. Note that while at almost 300 pages this is substantial, it’s also expensive, with a list price of $75.

11. John Lennon: The Collected Artwork, by Scott Gutterman (Insight Editions). Not so much a major volume as a useful fill-in-the-gaps collection, this features, just like the title says, collected artwork of John Lennon. As even many casual fans of Lennon and the Beatles know, many of these were fairly basic if humorous character sketches. Many of them are found in this volume, stretching all the way back to his childhood, though most of them were drawn when he was an adult. Basic text by Scott Gutterman provides the context, as does a foreword by Yoko Ono.

Also out in 2015: the expanded/revised/updated ebook version of my book Unknown Legends of Rock’n’Roll. Twice the size of the original 1998 print edition, it profiles 75 cult rock acts from the 1950s to the 1980s. The 60 chapters in the print edition have all been expanded, and there are 15 entirely new chapters. Click here for more info and to order: