Last year in this space, I wondered if there might be a slowdown in music history documentaries, considering the more limited access to many of the resources needed to produce them. Although there were still limitations on what we could do in all areas of life in 2021, these don’t seem to have affected either the quality or quantity of such docs. In some ways, the genre seemed healthier and to carry more weight than ever. Three of the top four films on this list—Get Back, Summer of Soul, and The Velvet Underground—were not only major achievements and popular movies, but also received a wealth of acclaim from the mainstream media and many viewers who weren’t even too familiar with the subject matter. A good number of the others got pretty big audiences and many positive reviews, if not quite as many as the aforementioned movies.

This doesn’t mean there wasn’t room for documentaries on more niche subjects, even if the upper part of my list probably doesn’t have many surprises. There were films on esoteric non-rock styles, like free jazz and experimental women composers, that were interesting even if those aren’t the kinds of sounds you usually listen to. Others spotlighted performers you would never have suspected to get the full documentary treatment just a few years ago, whether on the cult side (Poly Styrene, Lydia Lunch, Eric Andersen) or hitmakers who’ve long fallen out of fashion (Trini Lopez). And there were worthy efforts on non-musicians who’ve made an impact on the scene (Ben Fong-Torres), as well as ones focusing on record labels and radio stations.

No, I didn’t see everything that might have been considered for this list. I never do, and who does? There is, for instance, a new one on Dionne Warwick that has not yet been too accessible. Ones I like that I catch up on in 2022 will be a supplement to my list next year, as a few from 2020 that I didn’t see until this year are to this list.

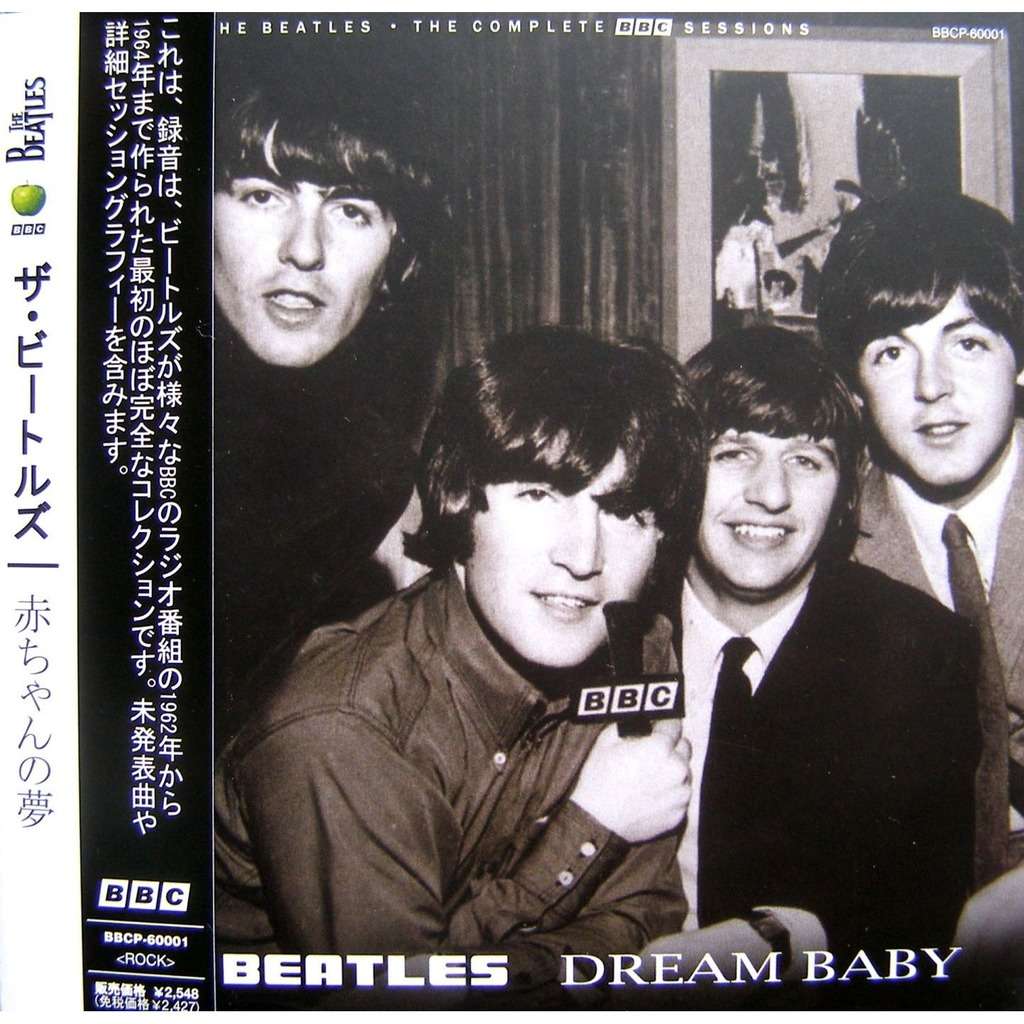

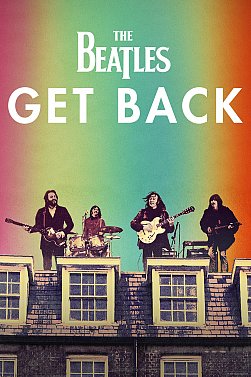

1. The Beatles: Get Back. No documentary—possibly any documentary, let alone a music documentary—got as much attention this year as Peter Jackson’s eight-hour, three-part series dedicated to the January 1969 sessions that produced the Beatles’ Let It Be movie and the bulk of their Let It Be album. He took more than 60 hours of film—little of which was used in the original Let It Be movie—and condensed it into a day-by-day look at what the Beatles were doing during that crucial month. The coverage, and acclaim, it received were deserved, if as much for the vast historical importance of the footage as what Jackson did with it. There is no other music documentary that gives us such a detailed look at the creation of a project, in this case a celebrated and sometimes infamous one by the world’s greatest group.

To get a little snobbish, though Jackson can’t be faulted for this, it isn’t as revelatory or now-known-for-the-first-time as some reviews believe it is. Virtually all of the music and much of the dialogue have been heard for many years on about 100 hours of bootlegs that were largely taken from the sound recorded on the original filmmakers’ equipment. Much of the dialogue, including some of the most crucial passages, was printed way back in 1970 in the book that came with the original UK edition of the Let It Be LP. Most of the music and dialogue was effectively summarized and analyzed more than twenty years ago in Doug Sulpy and Ray Schweighardt’s book Get Back: The Unauthorized Chronicle of the Beatles’ Let It Be Disaster. I did my own part to disseminate some descriptive analysis of these sessions in my 2006 book The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film. (Plug: Still available as a revised/updated/expanded ebook, with about 50,000 more words than the print edition.) Viewers, however, can’t be faulted for greeting much of this as new information, since only a relatively small percentage of Beatles and general rock fans have waded (as I have, I admit) through all of those 100 hours.

This is different and in some ways superior to these previous documents, however, and not just because it’s naturally going to be more entertaining and impressive with accompanying visuals (which are in excellent quality, and notably superior in clarity and color to the original Let It Be film). Numerous images without speech (especially facial expressions) convey some emotions that don’t transmit with mere transcription or audio-only recordings, like when Paul McCartney seems to nearly choke up into tears when it seems like John Lennon might not be coming into rehearsal after George Harrison quits about a week into the sessions. (John does make it, Paul getting called to take his phone call just as it seems like McCartney might break down). John, Paul, and Ringo Starr seem to have a let’s-stick-through-this-together bro-hug of sorts shortly after George (temporarily) quits.

Although dialogue sans visuals gives the impression Lennon callously thinks Harrison can be replaced by Eric Clapton after George walks out, an audio-only conversation between John and Paul secretly recorded by a hidden microphone tells a different story, with both obviously urgently concerned to get George back in the band. When George returns when sessions resume at Apple Studios, the way he and the others are joshing around make it obvious no serious grudges are being held. When Billy Preston joins in shortly after the filming moves to Apple, the whole band’s relief and joy at the lift he gives the sessions (the exact word “lift” is used by one of the Beatles) is palpable.

Jackson also effectively zeroes in on highlights of the numerous multiple versions of songs from rehearsals, especially bits that notably vary from the familiar versions, like a cha-cha pass through “The Long and Winding Road” and the numerous funny accents used on different takes of “Two of Us.” Subtitles tell us what the many brief snippets of unreleased songs they perform are, even if it’s just a line or two (or even a word or two), including not only some way-obscure covers, but also early Lennon-McCartney compositions and jams that only seem to have been officially titled with the making of this film. Subtitles also quickly identify the many associates and friends who are seen at points, from engineer/producer Glyn Johns to Paul’s brother Mike and Apple doorman Jimmy Clark (who has a more extensive and colorful role during the rooftop concert sequence than you might guess).

Much of the media spin on the Get Back film has been that the Beatles weren’t fighting as much or having as miserable a time during these sessions as most biographies have usually contended. It’s also been pointed out that many, maybe even most, bands have these kind of arguments and ups and downs in the course of extensive rehearsal and recording. That seems to be generally borne out by the film, but it’s not like this month wasn’t without its significant problems and tensions. One of the members—of a band in which each guy was crucially important—quitting less than ten days into the sessions was a major, even grave problem, although it was basically solved within another ten days. Some of the words, exchanged glances, and expressions make it apparent at various points that each of the Beatles have some differences of opinion that might not be fully expressed.

On the brighter side, Ringo–largely silent throughout the proceedings—has a “to the rescue” moment when he quietly but firmly lets it be known he wants to play on the roof, at a point where some of his bandmates seem undecided. When they finally do make it to the roof (for a concert that’s shown in full, if sometimes in split screen and with bits of dialogue from the crowd on the street and police), it’s exhilarating to see the laborious and sometimes fraught weeks of rehearsal paying off with an excellent live show, even if you’ve already seen much of it in the Let It Be film. The original Let It Be movie, incidentally, is not made redundant by this film—most Let It Be’s scenes are not repeated in Get Back, whether complete performances of songs like “The Long and Winding Road” and “Let It Be,” or their highly amusing tongue-in cheek cover of “Besame Mucho.”

It’s a tough call as to whether this or Summer of Soul (reviewed below) is the best music documentary of 2021. Summer of Soul is definitely more enjoyable and (owing to its much shorter two-hour length) accessible, and also of vast historical importance. Even some major Beatles fans might find the eight-hour length of Get Back to drag at times, especially when they’re continuing to rehearse some of the songs they’ve already worked out. But these sessions were of such historical importance, and documented in such unprecedented depth here, that I’m giving this the top slot, without any slight intended toward Summer of Soul.

You want some mild criticisms? Here are a couple. The last day of the sessions (January 31, the day after the rooftop concert) could have been represented more fully; scenes from these are shown in part of the screen while the end credits roll. (To be fair, much material from those sessions is in the Let It Be film.) And some of the very first subtitles read, inaccurately, that Paul was fourteen when he joined the Beatles (he was fifteen) and that George was thirteen (he was fourteen at the youngest, or could have just turned fifteen, when he joined sometime in early 1958). These dates are very well documented by numerous books, and not just known to hardcore obsessive historians. How does such a high-profile and well done project get them wrong?

2. Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised). In the summer of 1969, the Harlem Cultural Festival held six days of music in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park. The talent at these events was astounding, and much of it was filmed. Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson has assembled this nearly two-hour documentary around these semi-forgotten concerts, including footage of enough greats to fill up a paragraph. Among the performers are Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder, Sly & the Family Stone, the Fifth Dimension, the Chambers Brothers, Abbey Lincoln with Max Roach, Sonny Sharrock, Ray Barretto, Gladys Knight & the Pips, the Staple Singers, B.B. King, Hugh Masakela, David Ruffin, Mahalia Jackson, Herbie Mann, and the Edwin Hawkins Singers. Clips of all of these onstage are embellished with interviews from event organizers, members of the audience, and a few of the artists, like Wonder, Family Stone drummer Greg Errico, Mavis Staples, and two of the Fifth Dimension. The only drawback is one that might be considered a compliment: the performance excerpts are pretty short, and one wishes there were more, and at least some complete songs, even if that would have meant greatly expanding the film’s length. The cuts between artists and clips can be pretty fast, though there wasn’t much alternative to fit everything into two hours.

When I saw this through online virtual cinema streaming, there was an additional forty-minute interview with Questlove. Among his interesting observations were that there were more than forty hours of footage to draw from, although these weren’t totally unscreened prior to this film, since specials based around the concerts were aired on New York television. Asked if more of the footage might be made available, he said there would be enough to generate subsequent special editions, which would be valuable for those who want to see quite a bit more. Among the other notable parts of the interview were Questlove’s revelation that the footage might have been thrown out had the documentary gotten underway just a few weeks later, and that he’s working on a Sly & the Family Stone doc.

3. McCartney 3, 2, 1. Even as a huge Beatles fan, I’m not as over the moon over this three-hour, six-episode Hulu series as a few of my friends are. That’s a quick explanation as to why this isn’t #1, but this won’t be a bad news review, since the series is very good. Paul McCartney discusses many aspects of his music and his career with producer Rick Rubin, who’s wise enough to let Paul do most of the talking; ask him reasonable questions that often focus on the process of writing, playing, and performing music; and do so, unlike a good many media figures, in an understated fashion that’s not overly sensationalistic or sycophantic. Shot in moody black and white in a studio, the pair often isolate specific parts of Beatles (and a few post-Beatles) tracks as they discuss tunes, a big boon both for musicians/producers/engineers and general big fans. While they go over a few of his most famous early-‘70s solos songs (and a bit that postdate those), the emphasis is almost wholly on the Beatles, which McCartney seems fine with.

It’s true that many of these stories will be familiar if you’ve seen other documentaries and read a lot about the Beatles. Some of them will be familiar even if you haven’t experienced too many of those. But it’s always fun, and interesting, to hear Paul voice them with his usual ingratiating enthusiasm and knack for engaging storytelling. Some of the tales aren’t so oft-told. Just a couple of my favorites include how Phil Spector wondered why the Beatles bothered to put good songs on B-sides, since he never did; their response was that as record buyers themselves, they wanted to provide maximum value and not make listeners feel like they were cheated. The Moog synthesizer on “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” in Paul’s telling, was used in part because Robert Moog himself happened to be working with one in Abbey Road. Beatles experts will spot some stories he doesn’t remember accurately, such as recalling how John Lennon praised “Here, There, and Everywhere” when they played back the album it was on while in Austria to film Help!; that album, Revolver, wasn’t recorded until the following year. If you know enough to catch that, you’ll catch some others. But you likely won’t be bothered by occasional clinkers like that in what’s overall a highly entertaining and often insightful series.

4. The Velvet Underground. As a disclaimer, I am listed in the “thanks to” part of the credits for this Todd Haynes documentary, though my involvement was just a long phone call with a co-producer, and several follow-up emails with notes that might have been considered helpful. I’m also particularly close to the subject of this film, as one of my books, White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day, covers the group’s career in detail.

In about two hours minutes, this does colorfully convey many of the essential facets of this legendary band’s significance. There’s barely any surviving footage of the group and, sadly, no quality footage with sound from live performance. But Haynes did as much as possible with the source material, with plenty of photos (some rare); some scraps of film footage that to my knowledge have never been previously available, such as black-and-white (if silent) images of the Doug Yule lineup; and even a few bits of unreleased 1965 demos. There weren’t tons of interviewees, in part because some members and numerous associates are no longer around. Yet there are good memories from John Cale, Maureen Tucker, and others in the VU circle like Jonathan Richman, Lou Reed’s sister, guys from Reed’s pre-VU groups, Jackson Browne (who played and recorded with Nico around the time of her first album), and Sterling Morrison’s wife. Reed, Nico, Sterling Morrison, Doug Yule, and some others who weren’t interviewed are represented by spoken excerpts from tapes. And the entire 1965-70 period is covered (along with much pre-VU history), though it’s weighted toward the Andy Warhol era.

Even with two hours, it’s not possible to cover all or even most of the Velvet Underground’s interesting accomplishments. Still, there are some shortcomings to this documentary that should be noted. Original drummer Angus MacLise is just mentioned a couple times in passing. Billy Yule, drummer for a couple months in summer 1970, isn’t mentioned at all. Neither is the live Max’s Kansas City album he drums on, or for that matter the VU’s fantastic 1969 double live LP. The Doug Yule era, which saw some of their greatest performances (including those on 1969 Velvet Underground Live) and their great third LP and not-as-great 1970 album Loaded, is represented, but given far less space than the Cale lineups. The band’s birth is overcontextualized as part of the overall New York avant-garde arts scene, with quite a few minutes devoted to activities in that world that weren’t directly VU-related. A good deal of stock footage of ‘60s scenes and images not at all directly VU-related is used, at times trying too hard to keep a fast pace and fill up time and the screen.

It must also be pointed out that some chronology is juggled. Whether some events were sequenced out of order because it was felt to work better cinematically, I can’t say. However, if you were from Mars and didn’t know anything about the Velvet Underground before seeing this film, you might think the first LP was released before they played the Dom at St. Mark’s Place (though the album came out almost a year afterward); that Nico left the band after, not before, White Light/White Heat; and that Sterling Morrison left the band before Lou Reed did. Maybe there aren’t many people who care about such things. But it would have taken only some minor resequencing, and maybe a couple more minutes of running time, to put things right without diluting the quality of the viewing experience.

The preceding two paragraphs of criticisms might create the impression that the film isn’t worth seeing, particularly if you’re particular about VU details. That’s not the case. It’s entertaining and vividly illustrates some key aspects of the group’s enormous significance. You’d need a few more hours to tell the story with the thoroughness it deserves, and that’s not possible for a theatrical release, with a PBS multi-episode series probably even less likely. And for all those other details and more pinpoint accuracy, there are books that tell that story—mine, for instance, but others as well, lest this review seem like an infomercial.

5. 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything. The title, as well as some of the approach, of this eight-episode, approximately six-hour Apple TV Plus series might overstate the impact of the rock and soul music of 1971. There were a number of years where music had a big impact, some with a bigger impact, like 1964, 1967, and 1956. But there was a lot of interesting music being made in 1971; a lot of turbulence in the surrounding world; and a fair amount of interaction between those two camps.

This series covers a lot of it, from superstars like Marvin Gaye, the Rolling Stones, and the Who to acts who were just emerging (David Bowie) or whose influence was felt more in the innovative quality of their work than record sales (Gil Scott-Heron). There are tons of excerpts, if seldom too extensive, from vintage interviews and performances, and lots from non-musical events of the time, again spanning the famous/infamous (Richard Nixon) to less predictable junctures in African American activism, feminism, and censorship. Refreshingly, there are no talking heads. There are plenty of spoken interviews both vintage and recently done for this project, but these are heard on the soundtrack over period film clips, a la one of the top other recent music documentaries, Laurel Canyon. If this is a trend, here for once is one I can get behind, letting words and action speak for themselves instead of constantly cutting to static close-ups of people talking about what happened.

Sure, you can learn lots more about any of the musicians, albums, and sociocultural developments covered in other books (and sometimes documentaries) than you can here, since this covers so much but doesn’t linger on any one topic for too long. But if you’re okay to go with the flow and just appreciate seeing so many interesting and incisive bites in a binge—and not get agitated about some musicians not mentioned or included, whether Paul McCartney or Nick Drake—there are plenty of unfamiliar clips and interviews. The list could be long, but there aren’t many, if any, other places you’ll, for instance, see Mick Jagger being interviewed in the early 1970s in French or footage of Sly Stone working in a home studio, or hear comments by rarely interviewed Bowie manager Tony Defries. Much of the 1971 music heard on the soundtrack to complement some of the non-performance images is likewise hardly cliched, whether tracks by cult artists like John Martyn and Gong, or deep cuts by the likes of Curtis Mayfield and Stevie Wonder.

6. Poly Styrene: I Am a Cliché. The story of X-Ray Spex singer/songwriter Poly Styrene is interesting beyond her pioneering role in early British punk music. There are some gaps in this documentary; her brief pre-X-Ray Spex career as reggae singer Mari Elliott isn’t mentioned, and there’s not much discussion about how X-Ray Spex formed, their relationship with their record label, and how their discs were recorded. While I would have liked more of that, what’s here does a very good job of conveying the essence of her music and personality. Her daughter, Celeste Bell, provides much of the narration, often drawing upon her own mixed and volatile experiences having Styrene as a mother, without overdoing it. There’s quite a bit of vintage footage, ranging from sharp color to blurry black and white, of Poly in performance. And there are interviews—refreshingly, heard in voiceovers rather than the more standard talking heads—from a wealth of people who knew or were influenced by her, including Paul Dean and Lora Logic of X-Ray Spex; Poly’s sister and ex-husband; and members of numerous early punk and new wave bands like the Selecter and Special AKA.

In an hour and a half, the film covers many facets of her music and life, some of them disturbing. These include her songwriting, and frequent focus upon identity and consumerism (though her daughter notes she was a shopaholic for clothes); the inspiration she provided for other women of color in the punk/new wave scene; and her feeling an outsider owing to her mixed-race ancestry. On the more distressing side, also documented are her mental problems, which resulted in a misdiagnosis of schizophrenia rather than acute bipolar disorder; how X-Ray Spex’s trip to New York and well received gigs at CBGB’s nonetheless spurred some inner turmoil; and her entrance into the Hare Krishna community after X-Ray Spex split. Her return to musicmaking years later, and rapprochement of sorts with her daughter after she was largely raised by others, gets the bulk of attention in the final minutes, though it’s not unduly drawn out.

7. The Who Sell Out: Classic Albums. I’m not sure what the precise title of this is, but you’ll be able to find this documentary on The Who Sell Out album by using these words or some combination of them. Although it only lasts a little less than half an hour, it’s a good overview of this great 1967 record. There’s a good case that it’s their best one, though Tommy, Who’s Next, and Quadrophenia get more critical reverence and attention. By the time the superdeluxe edition of the record appeared in 2021 in conjunction with this film, lots of people involved with it were gone. But fortunately Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey weren’t, and give good and fairly detailed comments about The Who Sell Out’s conception and individual songs. Townshend notes, with amusement, that composer Speedy Keen pointed out the title of “Armenia in the Sky” was supposed to be “I’m an Ear Sitting in the Sky,” and declares “I Can See for Miles” was the best song he wrote, though his opinion’s been known to change multiple times on such matters.

There’s some period footage of the Who and managers Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp on and offstage, some seldom or never seen in other documentaries. A few surviving associates and journalists offer remarks, and parts of some tracks are isolated so you can focus on specific members’ contributions (though John Entwistle’s bass isn’t honored with any). My only reservation is that some of the songs aren’t commented upon, including standouts like “I Can’t Reach You” and “Sunrise.” Nor is it explained why the commercials linking the tracks petered out shortly after the beginning of side two of the original LP, though their placement and purpose are discussed. This was made available for free viewing on YouTube when the superdeluxe box of The Who Sell Out was released, though I don’t know if it’ll be up there for good.

8. Tina (HBO). HBO’s Tina Turner documentary is more oriented toward her personal life than her musical career, but doesn’t neglect the music she made on her own or with her ex-husband Ike. Although Turner’s long been retired, she was interviewed recently and fairly extensively for this picture, speaking about life both with and without Ike. It also benefits from a good number of interviews with other close associates, my favorite being Jimmy Thomas, who was in the Ike and Tina Turner Revue a long time. There are also plenty of vintage performance and interview clips (including some with the late Ike Turner) stretching back to the early 1960s, some of them rarely if ever before seen, though mostly pretty brief. It’s a pretty solid overview that doesn’t avoid the tough issues of Ike’s abuse of Tina, but doesn’t dwell unduly on them either.

As is par for the course for me on many such projects, I wish there had been more about the music. Her influence on Mick Jagger is fleetingly mentioned a couple times, but there aren’t specific details about this or their tours with the Rolling Stones, let alone any footage from those tours (although a sequence of Tina performing on the 1969 tour is in Gimme Shelter). The Turners’ success with soul covers of rock hits like “Proud Mary,” “Honky Tonk Women,” and “Come Together” isn’t discussed, and even the records from her spectacularly successful solo comeback in the 1980s aren’t covered in much detail, with the exception of the hit “What’s Love Got to Do With It.” The final segments kind of drag in a way common to how many documentaries of legacy figures get less interesting toward the end, though otherwise it’s a worthwhile watch.

9. Like a Rolling Stone: The Life and Times of Ben Fong-Torres. Best known as a writer and senior editor for Rolling Stone in the late 1960s and 1970s, Ben Fong-Torres has had a long career as a journalist, writing primarily though not exclusively about music. This documentary does focus on his Rolling Stone years, highlighted by audio excerpts from tapes of his interviews with major stars like Jim Morrison, Tina Turner, Stevie Wonder, and Marvin Gaye. Fong-Torres himself is interviewed extensively, as are some Rolling Stone colleagues and musicians. There’s also some interesting material about his background growing up as a Chinese-American in the Bay Area, and the murder of his older brother Barry, an activist in the Chinese-American community. The film conveys how fortunate he was to be on the ground floor of rock journalism when access to stars was considerably greater, and how seat-of-the-pants rock journalism was when Rolling Stone was the first widely circulated national publication to cover the music with seriousness. But it also conveys how Fong-Torres’s personable skills at making his subjects comfortable sharing information was an asset to his writing.

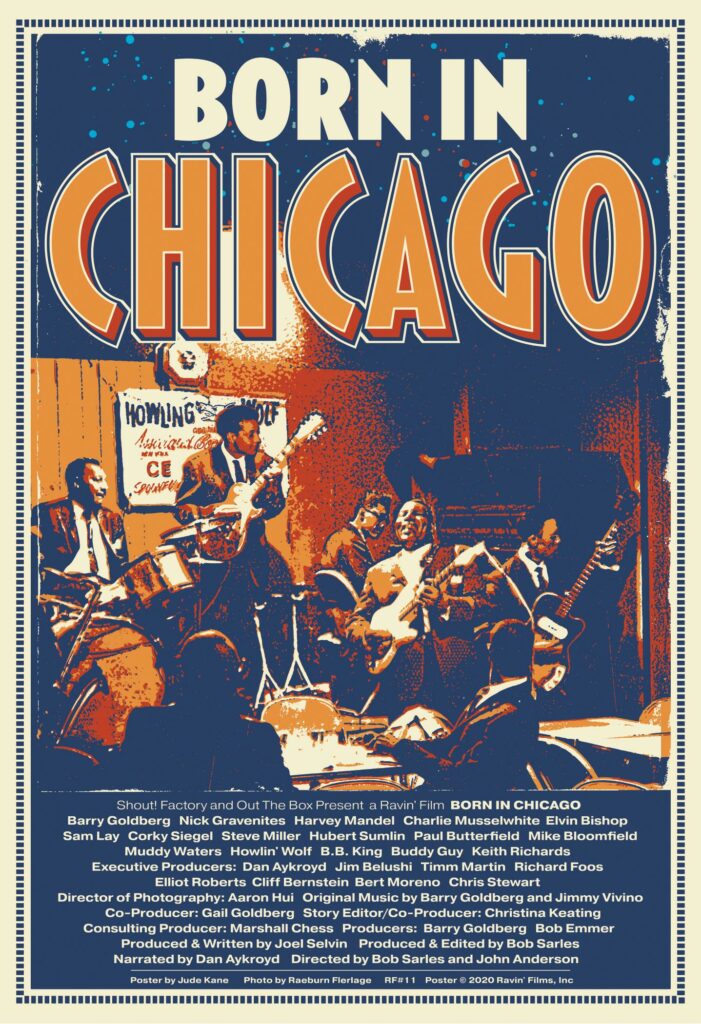

10. Born in Chicago. Although this bears a 2020 date, it didn’t premiere in North America until 2021, and I hope it doesn’t bother anyone that I’m putting it in these 2021 listings. This focuses on the 1960s Chicago blues scene, but particularly on how a young generation of white listeners emerged who played blues, sometimes becoming quite famous. Proper attention is paid to how electric blues became a Chicago trademark with the emergence of giants like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf in the middle of the twentieth century, but then the young white blues (sometimes blues-rock) guys get the primary attention.

The basic history laid out by the film and narration (by Dan Aykroyd) doesn’t offer new information for those familiar with the scene. The movie’s main value is found in excerpts of archival footage and, more notably, interviews with many of the principal figures that tell the story in largely interesting and colorful ways. Those interview clips span the mid-1960s to recent times, including comments by Mike Bloomfield, Elvin Bishop, Barry Goldberg, Steve Miller, Harvey Mandel, Nick Gravenites, Sam Lay, Buddy Guy, Charlie Musselwhite, and others. Also heard from are some rock musicians from other regions who have something to say about the movement, like Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, and Carlos Santana. The point’s made that the music served as a means to bring people of different races and artists together, though Chicago blues had very few white listeners when the 1960s started.

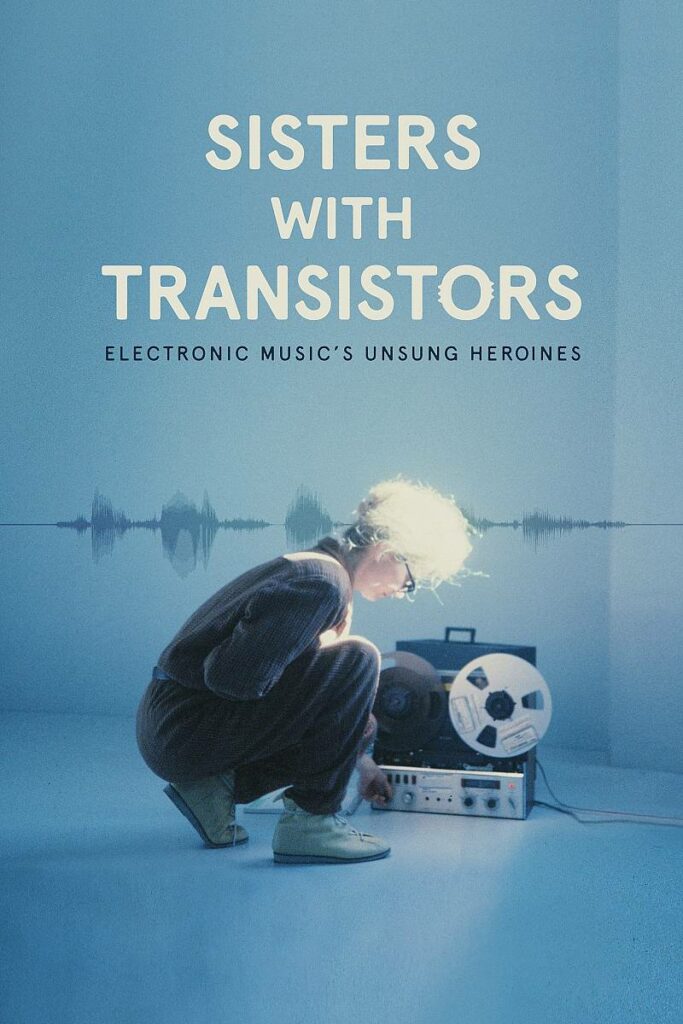

11. Sisters with Transistors: Electronic Music’s Unsung Heroines. In the twentieth century, numerous women were in the forefront of the development and creative application of electronic music. This documentary focuses on about ten of them, some of whose names might have some familiarity beyond the world of specialists of this field, like Wendy Carlos, Pauline Oliveros, and Theremin player Clara Rockmore. Some of them have been heard by wide audiences even if their names might not be well known, like Bebe Barron, who with her husband Louis composed the score for Forbidden Planet, and Delia Derbyshire, who arranged the theme for the Doctor Who television series. Others are more apt to be primarily known to followers of the avant-garde, like Maryanne Amacher and Elaine Radigue.

Even if, as it is for me, electronic music is not a big interest of yours, this is a pretty interesting film, and certainly well done. A considerable amount of vintage footage was unearthed of the artists in performances, and occasionally talking about their work. There aren’t any talking heads, but voiceover interviews, from both the artists talking about their work and other musicians discussing these figures, are featured, with narration by Laurie Anderson (whose own music isn’t covered in the film itself). Some of the clips are quite entertaining in their own right, like Suzanne Ciani performing live in the mid-1970s with a huge bank of equipment with intersecting wires; Rockmore playing the Theremin; and Amacher filmed in the early 2000s in a home that’s accurately described in voiceover as in frighteningly bad shape. Although the significance and struggle of women establishing themselves in the field isn’t emphasized as much as their actual music, important points about these are made, such as Carlos noting how few women score major Hollywood movies, and Amacher’s feeling that she wanted to do something more original and creative than push around notes by dead white men.

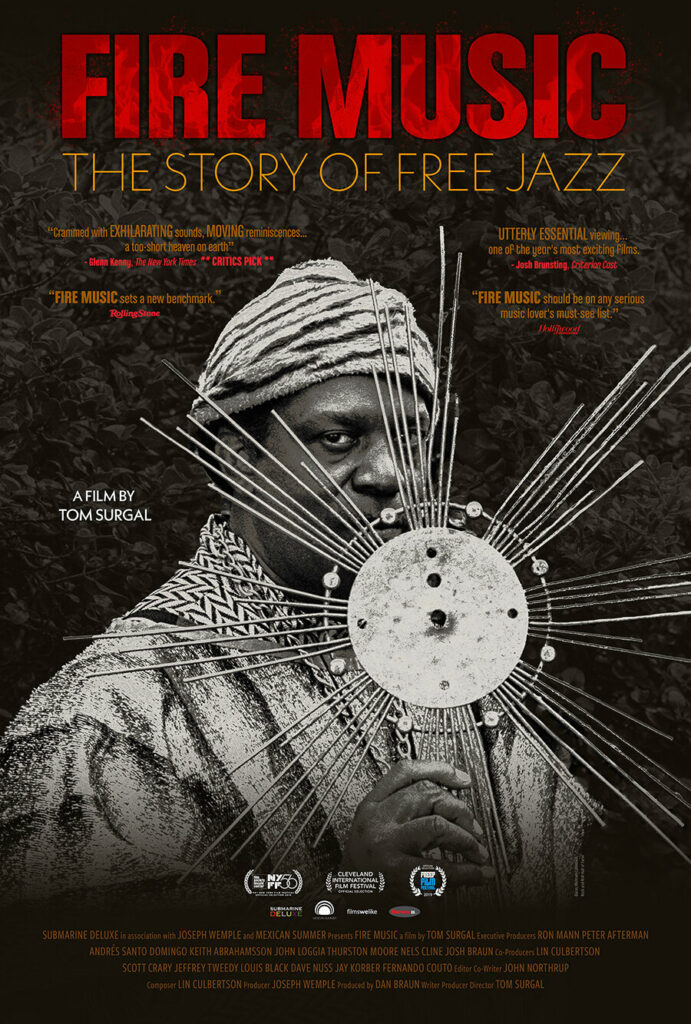

12. Fire Music: The Story of Free Jazz. Free jazz has been around since the late 1950s, but it’s the peak of the form—the 1960s, spilling over a little to the 1970s—that’s the focus of this film. Unlike free jazz itself, the format of this documentary is pretty conventional, mixing bits of choice archive footage and photos with interviews (both archival and done specifically for this project) with many of the key performers. That’s fine—although this doesn’t dwell on any one or several figures long enough for some specialists, it covers a lot of ground in satisfying fashion. The musicians represented by footage and/or interviews is pretty long, but includes such key players as Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Sun Ra, Carla Bley, Cecil Taylor, Albert Ayler, and Don Cherry. Plenty of others are seen and heard who might not have as high profiles, like Prince Lasha, Sonny Simmons, Burton Greene, Bobby Bradford, and critic Gary Giddins. The interviews are occasionally vague and rambling, but for the most part insightful.

As in any such project, you might wish some of the excerpts were longer, as they include some downright entertaining clips like Sun Ra’s band in colorfully gymnastic action; the Art Ensemble of Chicago in their striking onstage makeup; and Gato Barbieri playing outdoors on a rooftop. Although the New York scene understandably dominates the proceedings, to its credit the free jazz communities in Chicago and St. Louis are also covered, as are the pockets of free jazz players that emerged in Europe after US musicians had laid the groundwork. Also explored are the attempts by musicians, with varying success, to create organizations and collectives that gave them more artistic control than the standard music business often allowed, including the loft performances spearheaded by Sam Rivers. Of course this doesn’t cover everyone, and there might be fans that lament the absence of people from Sonny Sharrock to Pharoah Sanders, though some relatively un-famous figures like the percussion group M’Boom do appear. Although it’s not a notable flaw, perhaps a few minutes could have been added discussing the contributions of record labels like Impulse and ESP to documenting free jazz, as well as the ventures of more mainstream companies like Atlantic and Blue Note into the format.

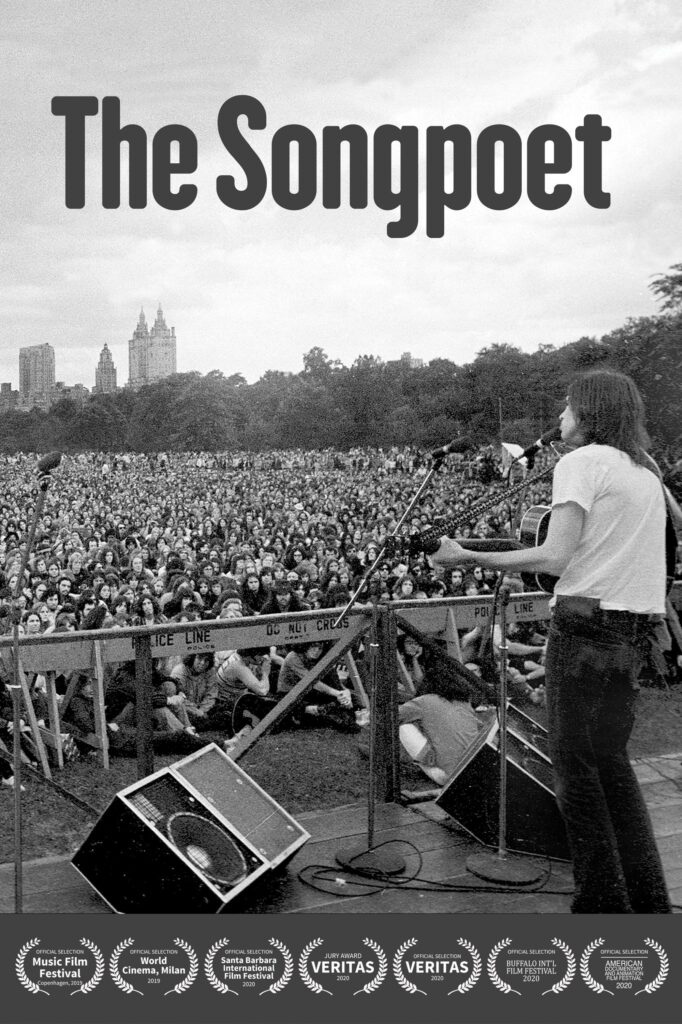

13. The Songpoet. How refreshing for PBS to broadcast a nearly two-hour documentary on a singer-songwriter who’s never sold many records, or even been widely claimed as a huge influential cult artist. His name’s not in the film’s title, but it’s on Eric Andersen, who’s been making folk, folk-rock, and country-rock records since the mid-1960s. As befits his music, this documentary is way lower-key and calmer than most retrospectives of careers by someone not hugely known to the general public. Besides interviews with Andersen and wives/girlfriends, peers of his from the ‘60s New York folk scene like Tom Paxton, John Sebastian, and Happy Traum also pitch in with memories. There’s not much vintage film of Andersen to draw from, but there are a good number of excerpts going back to a CBC mid-‘60s clip of “Thirsty Boots,” as well as lots of photos from the ‘60s to the present. Also noted are Brian Epstein’s plans to manage him before suddenly dying in 1967, and his brief appearances in Andy Warhol films.

While this does cover his whole career, more attention is paid to the ‘60s and early ‘70s than other eras, which is appropriate as that’s when his most popular work was done. “Popular” is relative; he never broke through to a wide audience, and although his most respected album, 1972’s Blue River, is referred to as a big seller, that’s not an accurate way to describe an LP that peaked at #169 in the charts. There could be more about his origins and his music; certainly some periods are barely or undiscussed, though Blue River benefits from stories from producer Norbert Putnam. The mystery of how his follow-up Stages was lost by the record company (and eventually discovered nearly two decades later) is also discussed, with hints that it was deliberately lost because Andersen had

displeased someone or some people at Columbia. This does build Andersen up more than non-cultists might find justified; his singing (which became a hoarse growl in recent years), compositions, and recordings are simply not as distinctive as Bob Dylan’s or Leonard Cohen’s, to name a couple high bars to match.

There’s a horrifying story in here, incidentally, and not one that reflects badly on Andersen, but on the ‘60s folk scene as a whole. He remembers playing the Philadelphia Folk Festival in 1967, where noted folklorist Kenny Goldstein announced Epstein’s death and declared he was happy the Beatles’ manager was dead, as the Beatles were bad for the folk scene. Not only that, according to Andersen, much of the crowd agreed with him. That’s way worse than purists yelling about folkies going electric. That might have been rude and wrong-headed, but they weren’t cheering a young man’s death. In his typically laconic and mild-mannered way, Andersen notes the incident led him to distance himself from that folk scene.

14. My Name Is Lopez. Trini Lopez is not a name that gets dropped by many hipsters these days, though he sold an enormous amount of records between 1963 and 1965. While not many would claim his sort of go-go fusion of rock, folk, Latin, and pop as markedly significant, he made some moderately enjoyable music and was truly significant as a Latino star in an era when there were few. Even if your interest in Lopez is moderate, as mine is, this documentary is worth seeing, as it’s very well done. Excerpts (admittedly very brief) from dozens of filmed performances in the (mostly) 1960s and 1970s are blended with extensive recent first-hand interviews with Lopez. While there’s a lot of footage of a recent modest-scaled concert, this has more purpose than most such things do in documentaries, since an historical Q&A Lopez did live on stage at the event is intelligently excerpted. For what it’s worth he’s in decent voice in that show, which has some added poignancy as Trini died of COVID-19 not long afterward, in 2020.

This isn’t just the story of his hit records, as Lopez recalls his family’s struggles growing up in Dallas, and the prejudice he suffered as a Latino entering the music scene. His climb to stardom included interesting interactions with Buddy Holly, Holly producer Norman Petty, the Crickets, Frank Sinatra, and the Beatles, whom he shared a bill with in Paris for a few weeks in January 1964. (He confesses he told an interviewer at the time that he didn’t think the Beatles would make it in the US, as the country already had a great rock group in the Beach Boys.) There are also unlikely snippets of duets with the likes of Vikki Carr; just a few comments from peers and associates like Dionne Warwick and Tony Orlando; and some coverage of his short acting career, which could have been bigger had he not left The Dirty Dozen when the production of that movie went beyond schedule. There’s nothing on his post-1970s activities save that recent concert, which is okay, as too many documentaries extend their coverage beyond the period in which an artist is truly of interest.

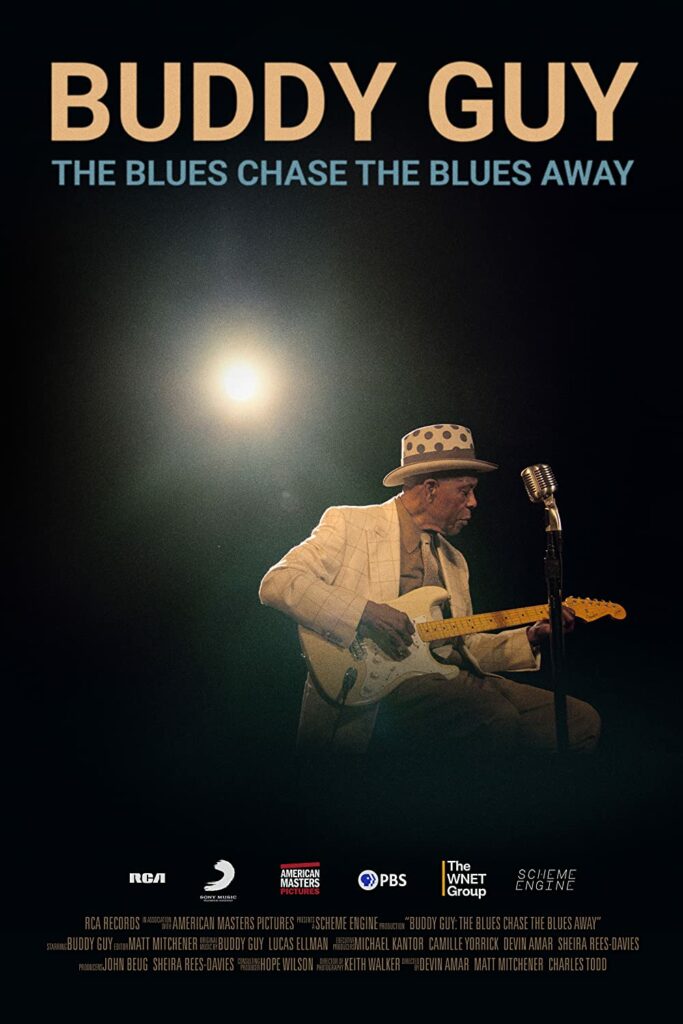

15. Buddy Guy: The Blues Chase the Blues Away. This American Masters PBS special on the blues great, like many episodes in the series, won’t tell you everything, or even a great deal, about the ins and outs of Guy’s career. There’s a book, Damn Right I’ve Got the Blues, and various liner notes for that. Which doesn’t mean this documentary isn’t without value, though there’s a lot it doesn’t cover about his recording career in particular. Its best feature is Guy himself, who talks extensively about his life in segments filmed pretty recently, when he was 84. These are interspersed with a very few vintage interview snippets, some choice (if too short) performance clips going back to the 1960s, and a few interviews with peers, associates, and acolytes, including Eric Clapton.

The perseverance he needed to get a foothold in the Chicago blues scene after moving there from Louisiana when he was a young man is covered in interesting detail. So is, with less detail but interesting memories, his mixed if overall positive experiences recording and touring with another blues great, singer and harmonica player Junior Wells. There is too much exposition on what the blues means by some of the interviewees, like John Mayer and Kingfish. I would have preferred more space for performance clips; sometimes it’s felt, here and in some other documentaries, like the producers are afraid viewers will switch channels if the excerpts last more than twenty seconds or so. Guy comes across as a humble but determined man, grateful for his eventual wide recognition but confident of the his talents, on vocals and guitar, that took quite a while to make a broad impact.

16. Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over. Directed by veteran underground/experimental filmmaker Beth B, this is a full-length documentary on the no wave musician/spoken word-performance artist that’s more straightforward than many of Beth B’s other movies (some of which have featured Lunch) and Lunch’s own projects. Lunch speaks extensively about her life and career in recent interviews, with a lot of performance footage going back to Teenage Jesus & the Jerks through shows from just a few years ago with Retrovirus. A few other people chip in with comments, like Thurston Moore and members of a few of her many bands, but Lunch is the main voice. Her pretty straightahead, if occasionally profane, and calm commentary contrasts, though not negatively, with the usually confrontational and explosive nature of the performance clips. Those include bits of 8-Eyed Spy and her work with Roland Howard, in addition to the bands previously mentioned.

As expected, Lunch speaks candidly about sex (including some early family abuse), power dynamics in relationships, and her urges to shock and oppose what’s expected of music and art in both the mainstream and underground. There’s more humor than you might expect from her standard public image, as when she observes that she and Nick Cave had nothing in common, but she and Rowland Howard (who was in the Birthday Party with Cave) had everything in common. There’s also some humor from the other interviewees, including Jim Sclavunos’s account of being deflowered by Lunch as a prerequisite of being allowed to join Teenage Jesus and the Jerks. It’s not the place to go if you want an easily digested linear overview of what she’s done; it jumps around chronologically, with too much attention and space given to Retrovirus, though the concluding segment with them is easily the best of the recent performance clips. It’s rather on the short side at 77 minutes, and if you wish it were longer, the companion oral history book (also titled Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over, reviewed in my best-of list for 2020) has way more detail, including quotes from many figures who aren’t in the film.

17. WBCN and the American Revolution. Although the official release date of this documentary was 2019, it doesn’t seem to have been widely seen until it was broadcast on PBS in late 2021. It also seems like the PBS version was substantially lengthened from the original to almost two hours, though it’s hard to know what to believe when you look for info about things like this online. At any rate, I’d rather include something like this that barely anyone seems to have seen before 2021 than leave it out because of its technical initial release date.

WBCN was the first underground FM radio station in Boston, and one of the most famous such ones in the country in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Music wasn’t the sole focus of the programming, and isn’t the sole focus of this documentary, which gives at least as much time to its news reporting and the explosive sociopolitical context in which the station operated. But there’s a lot about the music it played, and its alternative news coverage, which dove into plenty of important and controversial subjects, is also worth knowing about. The very well, if conventionally, done film is heavy on talking heads from the period, including many of the station’s DJs and employees, as well as its founder Ray Riepen, also a key figure in the establishment of the city’s leading rock club, the Boston Tea Party. There are excerpts of WBCN interviews and radio broadcasts with Patti Smith, David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen, and Jane Fonda. And a couple of the talking heads who pop up are unexpected inclusions for documentaries like this: Noam Chomsky and (if very briefly) colorful Boston Red Sox pitcher Bill Lee. A companion book was published in late 2021.

18. Mr A. & Mr M.: The Story of A&M Records. Mr A. was Herb Alpert and Mr. M Jerry Moss, who founded A&M Records in the early 1960s and ran the label for the next thirty years. This two-part, nearly two-hour documentary debuted on Epix near the end of the year, and covers the history with extensive interviews with the pair, as well as lots of archive footage of the company’s biggest stars. There’s some overlap—not in actual scenes, but in subjects covered—with the 2020 documentary on Alpert himself, Herb Alpert Is…. Understandably there’s plenty of attention paid to Alpert’s early records, which were crucial to launching the company. Otherwise the emphasis is very much on a handful of A&M’s biggest acts from the 1960s through the 1990s: Joe Cocker, Cat Stevens, the Carpenters, the Police, Suzanne Vega, Styx, Sergio Mendes, Janet Jackson, Peter Frampton, Carole King, and Supertramp. Not many listeners will be big fans of all of these big sellers from disparate styles, but that’s the kind of diversity that’s needed to become a power in the record business, and A&M didn’t have as much of a stylistic identity as other big indies like Motown, Stax, Elektra, or Atlantic.

The points are repeatedly made—too often, really—that A&M was an artist-friendly label and a great place to work, certainly at least for Alpert and Moss. Some of these could have been dropped or reduced for room on some of the more interesting cult artists or even commercial failures who recorded for the label, especially in its early days, like Phil Ochs, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Steve Young, and (very briefly) Captain Beefheart. A&M’s shrewd moves in picking up American rights for important late-‘60s British acts like Procol Harum, Fairport Convention, and the Strawbs are noted, but not detailed in depth. Some of their notable mid-sized acts who had some hits are barely present, like Chris Montez. Any big company must have had some interesting tensions accompanying pivotal decisions that could have worked both for and against the success and quality of its product, but these aren’t much of the story here, though the bittersweet fallout from its sale to PolyGram in the ‘90s is discussed. The result is a passable but rather bland overview of an important record company.

19. In Their Own Words: Chuck Berry. This nearly hour-long episode in the PBS series is kind of like a condensed version of 2020’s fuller-length documentary Chuck Berry, without the schlocky re-enactments that weakened that release. That means this shorter overview is actually superior, though neither one goes into the kind of depth a major pillar of rock like Berry deserves. There are exciting, but frustratingly very brief, archive clips of him in performance throughout his career, as well as some bits of interviews he gave for cameras. Family members (including his longtime wife) chip in with memories, as do Marshall Chess and Keith Richards, as well as some more peripheral figures. As for specifics about most of his many hits and classic compositions, well, you’ll have to do the more time-consuming but rewarding work of going through biographies, rock histories, and liner notes. This has some of the basics of his importance and creativity as a guitarist and songwriter, as well as hitting some key incidents of his career, including the jail stints that derailed him at several points.

The following documentaries came out in 2020, but I did not see them until 2021:

1. Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President (Kino Lorber). Jimmy Carter, it’s fair to say, had a greater passion for music, and better musical taste, than most presidents of our lifetime. This well done documentary examines those, with recent interviews with Carter, who remains well spoken and lucid well into his nineties. His admiration for Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, and the Allman Brothers is the most noted aspect of his pantheon, and Dylan, Nelson, and the late Gregg Allman are also interviewed. Not everyone Carter liked and engaged in his campaigns and causes was as critically esteemed; Jimmy Buffett and Garth Brooks are also heard from. It’s also true that he didn’t champion (if he was aware of them) edgier acts like Neil Young, Patti Smith, or Sun Ra. But he overall gravitated toward big names of good quality, and not just rock musicians (or even exclusively liberal musicians), as his fandom of several musicians who played at his rallies or government functions are also covered. Those included Dizzy Gillespie, Loretta Lynn, and Charlie Daniels, as a few examples.

It’s not always remembered that some of these musicians played a crucial role in raising funds for Carter’s presidential campaigns, especially the Allman Brothers, but also others. It’s certainly not often remembered that Carter actually sang, or more accurately chanted, the brief title lyrics to Gillespie’s “Salt Peanuts” at one event, as seen in a clip here. And it’s not often revealed, as Willie Nelson does in an interview, that Nelson smoked pot with one of Carter’s sons in the White House. The film is stretched a bit to feature length with some general coverage of Carter’s political accomplishments and struggles, with some comments by non-musical figures like Madeleine Albright, Andrew Young, and Carter’s son Chip. But the focus is mostly on the musical connections, and overall it’s a calmer and more even-handed assessment of the subject matter than the slightly hype-ridden approach many films bring to such topics. Also seen in vintage Carter-related performances and/or interviews are Paul Simon, Nile Rodgers, and Rosanne Cash.

2. The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart (HBO). This was among the most popular documentaries of 2020, but without HBO or a safe convenient way to watch it with others, I didn’t see this until spring 2021. The pluses are the standard ones for fairly lengthy music documentaries on big acts with plentiful resources. There are interviews with all three of the Gibb brothers in the group, though only Barry’s were done specifically for the movie, Robin and Maurice having died some years back. There are clips, if usually pretty short ones, going back to home movies and TV appearances in Australia before their move to London in 1967. Several close associates also speak, including, refreshingly, guitarist Vince Melouney, though it sometimes isn’t mentioned that the Bee Gees were a quintet when they rose to global fame in the late 1960s. Tensions between the brothers (which even led to them briefly splitting in the late 1960s) aren’t glossed over, though they realized then and almost always that they were worth a lot more together than apart.

While their late-‘60s pop hits get a lot of attention, more time’s given to their disco years. To strike a sour note that might annoy some fans, not everyone likes both phases, or certainly equally likes both phases. The late-‘70s were certainly their years of peak commercial success, but it’s my view that their earlier work from the 1960s and early ‘70s was not just better, but so dissimilar to almost be the sound of an entirely different act. Their stylistic transition is discussed at some length, which could make the later sections of interest even to some who aren’t fans of their later music. Or conversely, I suppose, make the earlier sections of interest even to some who aren’t fans of their earlier music. The film loses momentum after the ‘70s as there isn’t too much to say about their work afterward, though that final section isn’t too long, leaving their earlier years as the movie’s main focus.

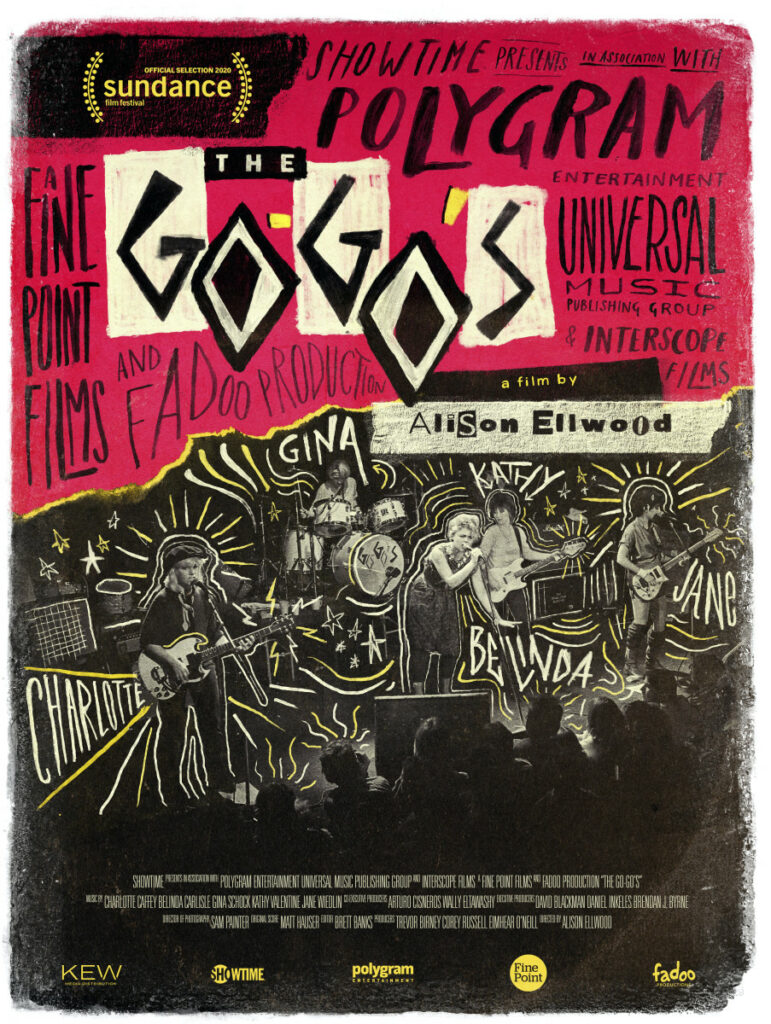

3. The Go-Go’s (Universal/Polygram). This hits all the points that should be required of decent, responsible documentaries. There are interviews with all five Go-Go’s from their most famous lineup, as well as the two early members who weren’t on their big hits, and the bassist (Paula Jean Brown) who joined for a while after Jane Wiedlin left. Also heard from are their manager (who got edged out after they became big stars, to the band’s eventual regret), Miles Copeland from IRS Records, and producer Richard Gottehrer. There’s a wealth of vintage footage dating back to their early punk years, though some fans might wish the excerpts were longer, and some live (if sometimes lo-fi) recordings form part of the soundtrack. Their problems are neither ignored nor highlighted at expense of the music, including Charlotte Caffey’s drug addiction, disputes over songwriting royalties, and fractious personnel changes. Wisely, just a few minutes are given at the end of their reunions, with the concentration on their half dozen or so years from their formation through the mid-1980s.

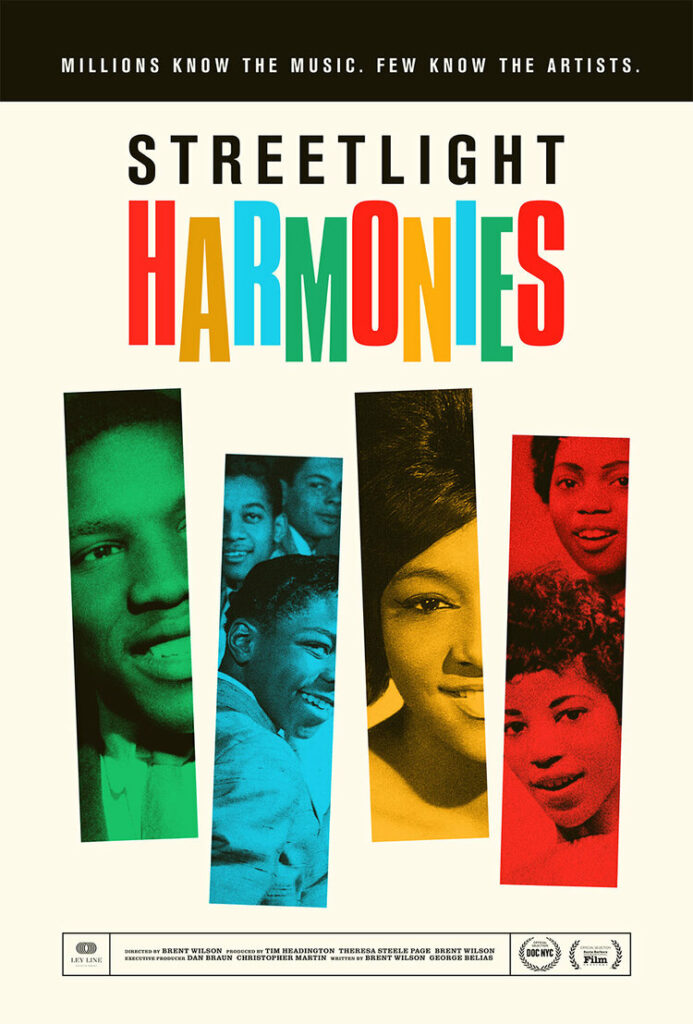

4. Streetlight Harmonies (Gravitas Ventures). Reversing the more common good points-bad points review sequence, let’s start with how some aficionados might pick on this doo-wop documentary. The style has a pretty extensive history, and especially as many of the notable groups only had one or two hits, many of them aren’t mentioned—some of them big ones, like the Diamonds. It jumps back and forth chronologically, and doesn’t present a linear history of how the style originated and developed. There are some excerpts of vintage clips, but they’re very brief, not numerous, and usually presented as crooked inserts in a larger graphic, where full-screen images would have been preferable. The last fifteen-twenty minutes stretch this out with some comments by doo-wop influenced artists from decades after the genre’s heyday, and a recording session from a few years ago in which some of the originals participated.

The good points make it worth viewing, however, mainly the interviews with a couple dozen or so figures. These include members of the Flamingos, Coasters, Crystals, Chantels, Five Satins, Drifters, Beach Boys, Little Anthony, and others, along with some knowledgeable historians and DJ Jerry Blavat. If the journey’s a bit haphazard, numerous topics are touched upon—not just the music itself, but also the difference between African-American and Italian-American groups; the difficulties in getting properly paid; the hardships of touring in the south; and the overlooked influence of doo-wop on surf music, with comments from Beach Boys Brian Wilson and Al Jardine. These stories, and the ingratiating way they’re told by these veterans, are the film’s strengths, though there’s much territory (like record labels and recording sessions) that could have been more thoroughly covered. In many regions, this can be seen for free on kanopy.com with a current library card.

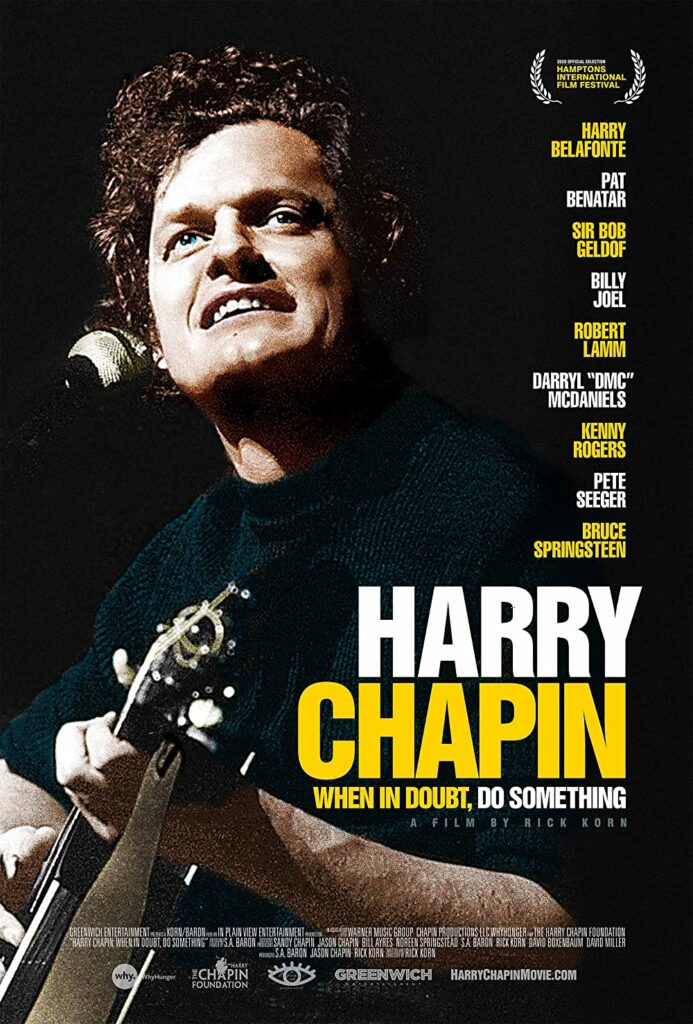

5. Harry Chapin: When In Doubt, Do Something. The intensity of the devotion of Chapin’s considerable fan base might only be matched by the distaste many critics have for the singer-songwriter’s long-winded story-songs. Whatever side you’re on, this is a pretty accomplished documentary, and might hold some interest even for those who don’t admire his music. That’s both because he was a significant figure on the 1970s pop scene—certainly as a commercial force, even if he wasn’t to everyone’s liking—and since he did more than almost any other celebrity, let alone popular musician, to work for progressive social issues.

There’s plenty of archive footage going back to his mid-‘60s folk days with siblings in the Chapin Brothers, as well as interviews with relatives, accompanists, Elektra Records chief Jac Holzman, peers like Billy Joel and Pat Benatar, and (though taken from a concert) memories from Bruce Springsteen. The enormous time and energy he spent lobbying politicians and doing benefits for progressive causes are detailed, as is the struggle to combine those with a commercially viable career and family life. The drawn-out concluding part on his death in a car accident and legacy might leave the impression the time couldn’t otherwise be filled with more coverage of his music and records. Even if your interest in Chapin is mild, as mine is, take heart—you don’t have much to lose by checking it out, since it can be viewed for free (with a current library card) in many parts of the US on kanopy.com.

6. Fat Boy: The Billy Stewart Story. Airing on PBS, this short (less than one hour) documentary covers the soul singer known for both his large size and unique phrasing. He used an almost stuttering sort of scat style and elongated buzzing noises, sometimes on popular standards. It’s not just short, but slight, and only gets on this list by virtue of giving some attention to a ‘60s soul vocalist who isn’t too well known, although he had some fairly big hits (with his radical interpretation of “Summertime” reaching the Top Ten). There are excerpts of just a couple vintage clips/interviews, and while there’s some silent color home movie-type footage of Stewart in concert, these short bits are often repeated, as if to cover the absence of other source material. A few people who knew and worked with Billy are interviewed, as are a critic and a musician of a subsequent generation, but they don’t say much of substance. The general point’s made several times that Stewart was unique and distinctive, but there’s surprisingly little specific detail or analysis of why that’s so, though at least it’s pointed out that he was significantly influenced by calypso.

A couple interesting stories do emerge, though one wonders if they might be somewhat exaggerated. It’s recalled that Stewart wanted songwriting royalties and credit for his version of “Summertime,” though it’s hard to see how that could have been obtained, even if he did a highly original arrangement. It’s also reported that he went to New York to try to get this through direct action, but was given an address that turned out to be composer George Gershwin’s grave. An exchange of gunshots between Stewart and Wilson Pickett on a bus is also reported, and one wonders what kind of argument could have been serious enough to risk death. The documentary’s worth catching if it airs on your PBS outlet, but isn’t nearly as significant as Stewart’s actual discography.