Throughout its history, rock music has always been deeply affected by sociocultural changes in the larger world of which it’s part. In my books, classes, and even my blogposts, I’ve concentrated on the music of rock, whether the performers, the records, or rock books and movies. I’m not often asked by rock fans to recommend books that aren’t strictly about rock music. Nonetheless, I’ve asked myself: what are some non-fiction books about the 1960s and 1970s that are not exactly about rock, but have much that relates to rock, or reflected how rock music changed the world?

There are many that could qualify on at least some grounds, even discounting fiction books that had a substantial influence on rock culture, like the Lord of the Rings trilogy and Ken Kesey’s work. Here, however, is a rundown of some of my favorites. Music figures strongly to slightly, but I’d recommend all to readers who want a sense of how rock’s effects—or energy similar to that driving changes in rock—rippled throughout our entire culture.

Many of my list-review combo posts rank them in order of quality, or at least my favorites. I find that hard to do with books that are in many ways so different from each other, so I’ve just put them in the order that flows best to me, with no numbers attached.

Season of the Witch, by David Talbot (Free Press, 2012). It’s refreshing when a book is both very popular and very good, like most of the best rock music used to be at its peak. That’s the case with the most recent entry on this list, Season of the Witch, which covers the changes undergone by the city of San Francisco in roughly a decade and a half, between the late 1960s and early 1980s. The Summer of Love and Haight-Ashbury are discussed, of course, but that’s just a part of the text, which moves on to how the ideals of the counterculture (and Establishment efforts to repress it) spread into community activism of all sorts in struggles over development, social justice, and the empowerment of ethnic minorities. The dark side of fringe radical movements is not ignored, with sections on Jim Jones, the assassination of Harvey Milk, and the SLA. It seems a bit strange to hone in on the 49ers’ 1982 Super Bowl victory as a triumphant/redemptive point for the city’s turnaround, but this is an engrossing read that weaves together many strands of San Francisco’s evolution during these crucial years, including its rock music.

The Haight-Ashbury: A History, by Charles Perry (Wenner Books, 1984). This is the best account of the neighborhood more identified with the psychedelic movement and the Summer of Love than any other. Music’s a big part, of course, but this focuses more on the Haight, the drugs, the radical groups who took root there like the Diggers, and the changes (or decline, really) the area went through as the Summer of Love passed. Perry was there as a participant and as a journalist (which included work at Rolling Stone), and this is unlikely to be surpassed as a social history of the Haight in the 1960s.

Rolling Stone Magazine, by Robert Draper (HarperPerennial, 1990). Although this covers the first twenty years or so of the history of the most famous rock music magazine, much of it’s devoted to the publication’s beginnings in San Francisco in the late 1960s and early 1970s. That puts it on the border of a book that’s as much about music as it is about publishing or other things. But it’s much more about Rolling Stone itself, how it reported on music and the counterculture, and how it changed drastically after it moved to New York in the mid-1970s than it is about rock. A very entertaining read heavy on anecdotes about major musicians and rock journalists, especially Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner. Like many such books, it also, sadly, reflects how ideals that fire a worthy enterprise at its genesis often get diluted and commercialized as time passes, particularly after success arrives.

The Rice Room: Growing Up Chinese-American from Number Two Son to Rock’n’Roll, by Ben Fong-Torres (University of California Press, 2011). The autobiography of longtime music critic and San Francisco media personality Ben Fong-Torres isn’t solely about rock’n’roll. But it has a lot of material about reaching adulthood in the midst of the Summer of Love, and becoming one of Rolling Stone’s first editors shortly after the magazine was founded in San Francisco. There’s also a lot about his family, and how rock and the radio were instrumental in making him take career paths and personal lifestyles that his parents did not expect or, at least initially, always endorse. Originally published in 1995, this recent reprint is slightly updated and expanded.

Days in the Life: Voices from the English Underground 1961-1971, by Jonathon Green (Pimlico, 1998). Moving from San Francisco to London, this 450-page oral history is by no means exclusively devoted to ’60s British rock music. But it has a lot of coverage of it nonetheless, and is great for the context of the counterculture in which UK psychedelic rock was born and thrived. About 100 figures are heard from in this absorbing volume, from musicians and producers to figures involved in the era’s British film, design, underground press, visual arts, clubs, literature, promotion, management, political activism, radio, TV, and more.

Give the Anarchist a Cigarette, by Mick Farren (2002, Pimlico). This verges on being a rock memoir as Farren was a cult rock musician as a member of the underground band the Deviants. But he was also a funny and talented writer, and this account of his career on both fronts in the 1960s and 1970s is a triumph of both style and content. It continues the story well past the Deviants (who are discussed quite thoroughly) through his time as a star NME writer in the ‘70s, all the way up to the punk era. Besides his memories of performing music, there’s a lot about the British underground press (in which he was actively involved) and the overall underground UK counterculture of the late 1960s and 1970s.

In the Sixties, by Barry Miles (Jonathan Cape, 2002). Another key figure in the British underground was Barry Miles, a personal friend of Paul McCartney and later author of McCartney’s own pseudo-memoir of the time, Many Years From Now. This is his own memoir of the period, during which he edited London’s leading underground paper, International Times, and ran Apple’s short-lived spoken word/experimental label, Zapple. (His time at Zapple is the focus of another book, the 2015 release The Zapple Diaries: The Rise and Fall of the Last Beatles Label.) As a book, this is less sharply honed, funny, and penetrating than Farren’s, but it’s still worthwhile.

Your Face Here: British Cult Movies Since the Sixties, by Ali Catterall & Simon Wells (Fourth Estate, 2001). This isn’t so much a general survey of British cult movies since the ‘60s as it is a collection of essays about a dozen particularly notable British cult movies spanning the 1960s to the 1990s. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, and this has outstanding pieces, totaling 300 pages in all, on films that are worthy of in-depth study: A Hard Day’s Night, Blow-Up, If…, Performance, Get Carter, A Clockwork Orange, The Wicker Man, Quadrophenia, Withnail & I, Naked, Trainspotting, Get Carter, and (in the only questionable inclusion) Lock, Stock & Two Smoking Barrels. Some of these, obviously, had quite direct connections to rock history (A Hard Day’s Night, Quadrophenia, Performance); some others caught the era’s rebellious or taboo-smashing ethos (If…, A Clockwork Orange), or at least used rock on their soundtracks. These aren’t conventional film critiques, but place most of the emphasis on telling the stories of how the films got made, spiced with plenty of behind-the-scenes stories and first-hand interviews with many of the actors, directors, writers, and other principals. What’s more, in many cases the authors identify specifically where famous location scenes in the movies were filmed in Britain, knowing that the kind of people likely to read these sort of books are precisely the kind of cultists that like to visit the actual places in the films if possible. The hard information is balanced by some insightful criticism, as well as some sharp general observations about what makes a cult film “cult,” and why these films struck particularly devoted chords that have enabled them to build staunch followings over the course of years.

Take 10: Contemporary British Film Directors, by Jonathan Hacker and David Price (Oxford University Press, 1991). It’s more scholarly and less breezily accessible (though still highly readable) than Your Face Here, and not as geared toward films with a cult or cult rockish sensibility. But Take 10 is still worth attention for those interested in the cutting edge of British film in the latter part of the twentieth century. There are essays on and interviews with ten filmmakers, some of whose work is also discussed in Your Face Here, such as Nicolas Roeg and Lindsay Anderson. Other directors featured include one who was quite actively involved (in his 1977 film Jubilee) in documenting the UK punk scene, Derek Jarman, as well as other big names like Stephen Frears, Bill Forsyth, Kenneth Loach, and John Schlesinger.

Creative Differences: Profiles of Hollywood Dissidents, by David Talbot & Barbara Zheutlin (South End Press, 1978). Though perhaps not as oriented toward the counterculture as Your Face Here, this has extremely interesting profiles (incorporating first-hand interviews) of directors, actors, and others in the film industry who struggled to make more personal, political, and ideologically meaningful movies than Hollywood wanted or accepted. It extends from the Cold War/McCarthy blacklist era through the 1970s, two of the more famous subjects being Medium Cool director Haskell Wexler and Jane Fonda. It was not until writing up this listing that I realized co-author David Talbot is the same guy who wrote, quite a few years later, Season of the Witch (see first entry).

Woodstock: An Inside Look at the Movie That Shook Up the World and Defined a Generation, edited by Dale Bell (Michael Wiese Productions, 1999). Not as well known as it should be, this is a fascinating inside look at Woodstock, the movie—not Woodstock, the rock festival—from the perspectives of those who worked on and produced the film. Verging on an oral history, it has extensive memories from directors, producers, camera operators, and, yes, musicians who played the festival. Like the festival, the movie was a seat-of-the-pants operation that needed some miracles to get pulled off. Histories of Woodstock usually emphasize the music, but it was the film that did the most to pass it into legend, and here’s the story from the other side of the camera.

Woodstock: The Oral History, by Joel Makower (Tilden Press, 1989). Despite its considerable heft (350 pages), this too does not focus especially on Woodstock’s music. Instead, the concentration is on Woodstock the event, as told from the perspective of the organizers, promoters, medical staff, food vendors, political activists, area residents, and yes, occasionally the musicians. In fact, there’s not much material here from the musicians, which might disappoint some readers. But Woodstock, for both good and bad, wasn’t just a big music festival—it was an epochal happening, recounted here only about two decades after it happened, when memories of what took place were at least somewhat sharper.

Diaries 1969-1979: The Python Years, by Michael Palin (Thomas Dunne, 2006). Monty Python have been sometimes hailed, rightfully I think, as something of the Beatles of comedy, combining great individual talents into an entity more than the sum of its parts. Their irreverence, first on TV and then with their movies (and some various side/solo projects), was as groundbreaking and taboo-breaking in its way as what was often taking place in rock music. Some of their biggest fans were rock stars, some of whom helped fund Monty Python & the Holy Grail. As one of Monty Python, Michael Palin was right in the middle of it. Remarkably, considering how busy he and his group were, he found time to keep extensive diaries for their first decade. Some of the early ones, unfortunately, were lost, but in any case, they became much more extensive and reflective as the 1970s progressed. The ways in which Monty Python helped change the status quo, and were themselves changed into something bigger and unpredictably influential, in some ways mirrored the same process at work in rock bands like the Beatles. Palin documented it with the same kind of verve and wit he brought to his work in Monty Python, though this is naturally a good deal more serious and less silly than some of the group’s famous sketches.

Palin’s next two volumes of diaries, covering 1980-1988 and 1988-1998, just aren’t as scintillating, much as reading about the Beatles’ solo years isn’t the joy you get from reading about the years in which they worked together. Other worthwhile Python books that are more standard biographies or oral histories include The Pythons Autobiography By the Pythons, a coffee table first-hand oral history that’s kind of their counterpart to the Beatles’ similarly formatted Anthology; David Morgan’s Monty Python Speaks!, another oral history with entirely different contents; and Kim “Howard” Johnson’s more fan-oriented The First 20 Years of Monty Python, which still has much fun behind-the-scenes details of all of the episodes of their TV programs.

The Prisoner, by Alain Carrazé & Héléne Oswald (Virgin, 1989). Just as Britain gave us the two best rock groups of the 1960s in the Beatles and Rolling Stones, so did it give us the two best TV programs of the time, Monty Python’s Flying Circus and the much different, far graver The Prisoner. The Prisoner brought up many of the issues rock music and the counterculture were also examining in the 1960s: the questioning of authority, rebellion against conformity, the abuse of power, and the nebulous nature of reality itself. There have been a few books about the series, and my favorite is this sumptuously illustrated coffee table one (translated from the original French) that details and examines each of the seventeen episodes. Also good, if more modest in production values and fannish in approach, is Matthew White and Jaffer Ali’s The Official Prisoner Companion.

Ball Four, by Jim Bouton, edited by Leonard Shecter (Turner, 1970). A sports book, in a post devoted to books that reflected how rock was changing and changed by larger society? True, there’s not much rock music in Ball Four (though there’s some; check out one of my previous posts for the lowdown). Yet Ball Four—still, almost 50 years later, the most famous sports memoir—brought something of the era’s rock rebellion into the wide world of sports, a much more conservative one than the music business, even if many ballplayers were (like most of the era’s rock musicians) in their twenties. Bouton was, like many rock musicians, nonconformist, willing to speak his mind with unpopular opinions, and irreverent toward conventions that wanted employees (i.e. athletes) to keep their mouths shut and not rock the boat. He was also very funny—something that distinguishes Ball Four from other tell-all memoirs as baseball loosened up in the next few decades. Some other memoirs have been hailed as worthy cousins to Ball Four, and I’ve tried some (such as Bill Lee’s), but none seem, to use baseball terminology, even in the same league. Maybe part of that well-written wit is down to sportswriter editor Leonard Shecter, whom Bouton has never shied away from crediting as a collaborator. I have to think, however, that much of it is down to Bouton just being a naturally funny and insightful storyteller who’s not afraid to shoot sacred cows. This has come out in various slightly expanded editions with afterwords going over some of his post-Ball Four life, the latest (and presumably last) one being 2014’s Ball Four: The Final Pitch.

Loose Balls: The Short Life of the American Basketball Association As Told By the Players, Coaches, and Movers and Shakers Who Made It Happen, by Terry Pluto (Fireside, 1990). Along the same lines, we have this less famous oral history of the ABA, which in its way brought a rock’n’roll sensibility to pro basketball and all of major league sports. It jazzed up the game with three-point plays, dunks, flamboyant stars, and flag-colored balls, even as it perennially teetered on the edge of disaster with its fly-by-night organization and finances. Some of the players had excesses on par with rock stars too, especially Marvin Barnes. My favorite story, related by Bob Costas in the book, is when Costas asked him for an interview, which Barnes said he would grant if he’d drive him to visit some friends. When Barnes didn’t come out of his hotel room, Costas called, only for Marvin to tell him, “Listen, Bro, why don’t you go see those dudes without me?” To which Costas pointed out, “Marvin, I don’t want to go see those guys, whoever they are. I don’t even know those guys.” To which Marvin responded, “Oh…yeah.”

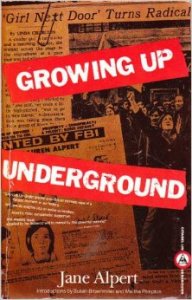

Growing Up Underground, by Jane Alpert (Citadel Underground, 1990). Alpert spent four years in hiding for her role in New York bombings by radical groups. I’ve found most of the memoirs I’ve read by radical ‘60s/‘70s activists to be self-righteous justifications of their behavior, often for some mistakes they made that hurt others. Alpert’s autobiography is an exception, as a more balanced and thoughtful portrait of why she and others felt it so urgent to take drastic steps for social change, acknowledging in hindsight the missteps, dogma, and naive ignorance that often hindered their progress. There’s not much about music, but an interesting passage notes how she played Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline—not one of his biggest hits among critics even at the time of its 1969 release, though it was pretty popular with the public—over and over again. Perhaps she found in it a mirror of her own hoped-for-journey to the end of the rainbow after the revolution had eradicated global injustice. As she observed, “In the beginning of his career he [Dylan] had struggled so hard to be himself that his voice had always been strained, his lyrics contorted and difficult…. Now, at 28, he was a survivor, had fallen in love again, had discovered that life could be startlingly, lyrically easy.”

Another memoir that I’d give more a more qualified recommendation to is Cathy Wilkerson’s Flying Too Close to the Sun: My Life and Times As a Weatherman, which also is willing to examine the flaws of the movement along with its strengths, and integrate some interesting personal autobiographical detail with the more political material.

And an honorable mention to:

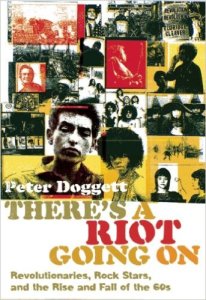

There’s a Riot Going On: Revolutionaries, Rock Stars, and the Rise and Fall of the ’60s, by Peter Doggett (Canongate, 2007). This does cross the boundary of being more about music than society or another subject. But it’s a large (nearly 600-page), extensively researched, and acutely perceptive examination of the relation between rock and revolutionary politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s, equally emphasizing the music and the social activism. Doggett’s more recent Electric Shock: From the Gramophone to the iPhone: 125 Years of Pop Music is more about music than society, but also often draws on cultural context to examine the many stylistic and technological changes that popular music has undergone since it was first reproduced and sold.