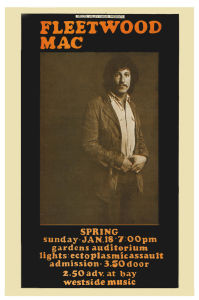

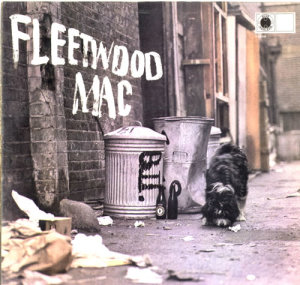

To most people—certainly most people in the US—Fleetwood Mac are most known, indeed often only known, for the lineup that produced massive hits from the mid-1970s onward, especially the Rumours and Fleetwood Mac albums. Many people—again, especially Americans—are wholly unaware that Fleetwood Mac began as a much different blues-rock group, and had a lot of success in the late 1960s before undergoing a bunch of lineup changes. The first major change was the loss of Peter Green, their original principal guitarist, singer, songwriter, and overall visionary.

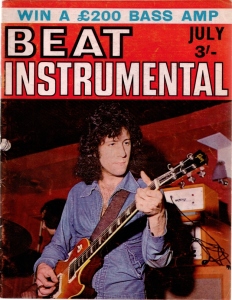

As a guitarist, Peter Green was the master of a biting, sustain-laden bittersweet tone. As a songwriter, he celebrated both joy and despair (if more often the low than the high) with a naked honesty rare in rock, and the equal of the African-American blues greats who’d inspired him to become a musician. While his singing was on the rough and husky side, it excelled in projecting idiosyncratic character and personality as unvarnished and devoid of pretense as his songs.

Peter Green was a major figure in late-‘60s rock, and one who still hasn’t achieved the recognition he deserves, even though a few of the songs he wrote and sang with Fleetwood Mac were big British hits. In part that’s because memories of his time with the band have been superseded by the much more famous records they made after Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks joined. By that time, the main remaining similarity with the band’s early days was the Fleetwood Mac name.

Yet it’s also in part because Green’s 1967-1970 recordings with Fleetwood Mac were quite uneven. The best early Fleetwood Mac tracks were those on which he sang (and, when they weren’t covering other people’s songs, wrote). These are interspersed, however, with quite a few sides featuring Jeremy Spencer as lead singer/guitarist and/or writer, and some (after mid-1968) on which Danny Kirwan takes those roles. Some of those are pretty good, but the distance between their abilities and Green’s is substantial.

This comment won’t endear me to some fans of the band, but some of Spencer’s tracks are quite mediocre and repetitious. Even Jeremy himself conceded in an interview with me that by the time the group recorded their third album, 1969’s Then Play On, he’d run his Elmore James style of blues into the ground. The best of those tracks in that mold were good, but he was limited to that form of blues and early rock’n’roll satires that aren’t all that funny, at least on record. Someone who was there at their early concerts once scolded me for offering that opinion, declaring that if you were in attendance, they were hilarious. Well, I wasn’t there (I was seven when They Play On was recorded), and maybe that’s my loss, but Jeremy’s rock’n’roll parodies can be a comedown when interspersed with Green’s penetrating blues-rock.

Kirwan’s songs were not so much comedowns in company with Green’s as slighter than the leader’s. As they’re usually lighter in mood, they make for nice contrasts with Peter’s material. But they’re not as close in distinction to the main act’s primary songwriter or songwriters as, say, George Harrison was in the Beatles, and Peter Tosh was in the Wailers. Kirwan also had a fairly high percentage of original material on the releases in Green’s latter days with the band, which makes for imbalance and lack of consistent quality. Perhaps in time, Kirwan might have grown more into his responsibilities, and the gap might have narrowed; Peter and Danny were already a formidable lead guitar team of sorts. But we won’t know what might have happened, since Green quit Fleetwood Mac in early 1970, less than a year after Then Play On.

What’s the ideal disc, then, to get a concentrated dose of Green’s talents? There isn’t one, actually. All of the Fleetwood Mac discs on which he played are still in print (along with quite a few live concerts and BBC sessions). But all of them, even the compilations, mix Green-dominated tracks with ones, often notably inferior, on which other guitarists and singer-songwriters have the spotlight. And some of the cuts with Green at the forefront aren’t that great, though these are largely confined to Fleetwood Mac’s second album, Mr. Wonderful, and some of the band’s many outtakes/live tapes.

With today’s technology, however, you can make your own ideal CD-length playlist of the best Peter Green. What follows is the track listing, with annotation, of mine, clocking in at just under the 80-minute limit of commercial single-disc CD releases. Of course every fan would compile a different selection of tracks given his or her rein, and many would object vociferously to the some of the inclusions, omissions, or sequencing on the one I assembled. I do think this disc comprises a solid summation of Green’s greatness, or, as some hucksters would have it, “all killer, no filler.”

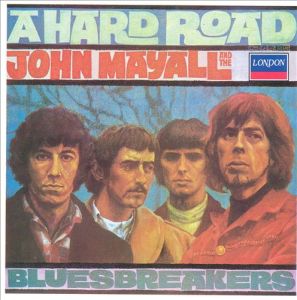

This disc goes in roughly chronological order, though I made a few exceptions when I thought a non-chronological ordering simply sounded better. I also took the liberty of including a couple outstanding tracks from his brief time (between about mid-1966 to mid-1967) with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, which kick off this imaginary compilation CD.

1. The Super-Natural (from A Hard Road by John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, released February 17, 1967). Although most of the tracks Green did as part of the Bluesbreakers featured leader John Mayall as lead vocalist, there were some that gave Peter the spotlight. This highlight from the sole LP Green did as part of the band, A Hard Road, is a splendid fierce instrumental showcasing Peter’s trademark searing sustain. It was also a huge influence on Carlos Santana, who wrote in his autobiography The Universal Tone (co-written with Ashley Kahn and Hal Miller), “On ‘The Super-Natural’…Green’s guitar sound was on the edge of feedback. That track left its mark on me. I think it was the first instrumental blues that showed me that the guitar could really be the lead voice, that sometimes a singer is not necessary. And I loved that tone.”

2. Out of Reach (B-side of John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers single “Sitting in the Rain,” released January 1967). Written and sung by Green, this was a magnificent despondent downer of a blues classic, both for Peter’s tortured vocal and the icy, reverberant guitar tone that would become one of his trademarks. As it didn’t appear on LP at the time, and subsequently only appeared on rather out-of-the-way compilations, it’s still not nearly as well known as it should be. In-the-know fans of British rock did pick up on it, however. When Trouser Press did a reader’s poll quite a few years later for the best B-sides that were better than their A-sides, “Out of Reach” was one of the top picks.

A few other tracks on which Green played (and sometimes sang) with the Bluesbreakers, like the outtakes “Please Don’t Tell” and “Missing You” (first released in 1971 on the John Mayall compilation Thru the Years), were also good. The rest of these selections, however, were recorded by Peter as part of Fleetwood Mac.

3. I Loved Another Woman (from Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, released February 24, 1968). With its minor-keyed melody and Latin-flavored beat, the arrestingly haunting “I Loved Another Woman” quickly demonstrated that there was more to Fleetwood Mac, and more to Green specifically, than standard 12-bar electric blues. It also anticipated the Latin flavor of another, much more famous song he’d soon record with the band, “Black Magic Woman.

4. Looking for Somebody (from Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, released February 24, 1968). For this track from Fleetwood Mac’s debut LP, Green didn’t even touch his guitar, delivering a doleful lyric to an equally doleful harmonica and the stuttering sparse, hypnotic beat of the McVie-Fleetwood rhythm section. Though close to standard blues in form, this has a lackadaisical irreverence that sets it apart from the Chicago blues he and the band obviously revered as their chief influence.

5. Black Magic Woman (single, March 29, 1968). The first of these songs to be familiar to the average rock listener—though this specific version isn’t well known to the average rock listener. Indeed, most people don’t know that the original version of “Black Magic Woman” was not by Santana, who had a huge hit with it in the early 1970s, but by Fleetwood Mac, and written by Peter Green. “Black Magic Woman” developed the tentative Latin-minor blues he’d explored on “I Loved Another Woman” into a tour-de-force. His wavering sustain wove a sorcerer-like spell wholly in keeping with the magic woman lamented in the lyrics—actually Green’s real-life girlfriend Sandra, whose own spell of celibacy was causing Peter no end of frustration.

Although it marked a definite break from the 12-bar blues that had been Fleetwood Mac’s mainstay, “Black Magic Woman” had definite roots in the unusual minor-keyed blues of Chicago blues great Otis Rush. The rolling Latin rhythm, and even the break into a more evenly spaced shuffle near the end, strongly recall the tempos employed on Rush’s 1958 single “All Your Love”—a song Green undoubtedly would have been familiar with, as it kicked off John Mayall’s 1966 Bluesbreakers with Eric Clapton LP (on which Fleetwood Mac bassist McVie actually played).

Even so, Peter and the band put a lot of their own personality into “Black Magic Woman,” which has an almost basement garage feel in comparison to the much more famous cover by Santana. Featuring the lead guitar work of a star who counts Green among his greatest influences, Santana’s version reached the Top Five in the US at the end of 1970. Inexplicably, the original version made only #37 in the UK (and failed to chart at all in the US), and many fans of both bands remain unaware to this day that Fleetwood Mac did it first.

6. Need Your Love So Bad (single, July 5, 1968). A cover this time, this one of a mid-‘50s R&B/early rock tune by Little Willie John, though Green decided to record it after hearing a version by B.B. King. As both a concession to commerciality and an adventurous wish to explore something beyond the blues barriers, strings were used in the arrangement (by American guitar great Mickey Baker, who as half of Mickey & Sylvia had a big 1957 hit with “Love Is Strange”).

There was still plenty of blues and soul in Green’s vocals and delicate, heart-rending guitar. Recorded, like “Black Magic Woman,” without Jeremy Spencer—something that would happen more and more at Fleetwood Mac sessions as the ‘60s drew to a close—it did hardly better than “Black Magic Woman,” peaking at #31 in the UK, and not even getting released in the US.

7. Fleetwood Mac (from The Original Fleetwood Mac, released May 14, 1971). We’re out of chronological sequence here, as this was actually recorded around mid-1967 before the band had properly formed, and not released until the 1971 outtakes collection The Original Fleetwood Mac. Nonetheless, it’s a propulsive, moody instrumental that assumed more historic importance when Green used the title of the song as the name of his new band with fellow ex-Bluesbreakers Mick Fleetwood and John McVie, Fleetwood Mac.

8. Love That Burns (from Mr. Wonderful, released August 23, 1968). One of the few highlights from the generally disappointing Mr. Wonderful album, “Love That Burns” was a slow-burning soul ballad with horns. It was very much in the mold of “Need Your Love So Bad,” but this tune was an original, not a cover, with a woozy sadness that took it into yet more melancholic territory.

9. Homework (from Blues Jam at Chess, released December 5, 1969). Actually recorded in early 1969, the super-session Blues Jam at Chess, on which Fleetwood Mac recorded/jammed with Chicago blues stars, was like many such combinations more disappointing on record than it looked on paper. The one exception is the magnificent version of Otis Rush’s anguished “Homework,” featuring stinging, wailing Green guitar and vocals, Otis Spann’s piano being the only non-band augmentation. Rush’s obscure original version is good, but this is at least its equal.

10. Albatross (single, released November 22, 1968). A huge #1 single in the UK, yet a near-total-misfire in the US (where it just missed the Top 100, peaking at #104), “Albatross” was very much a departure for Fleetwood Mac. Not yet even a year and a half old at the time this was released, the group were nonetheless very much known as a blues band. Even more than “Black Magic Woman,” this was a single that was bluesy in feel and spirit without sticking to the rigid melodic or structural format that typified much classic American blues.

Recalling Santo & Johnny’s similarly dreamy 1959 instrumental smash “Sleep Walk,” the meditative mood of “Albatross” was drawn out by a throbbing undercurrent of mallets and cymbal washes that built to periodic crescendos. Recorded at their first session with Danny Kirwan (who made the band a quintet after joining in August 1968), it was also an influence on the biggest band of all, George Harrison citing it as “the point of origin” for the Beatles’ “Sun King” in an interview with Musician. Here’s a little known footnote that’s not in my Fleetwood Mac book: this was used on the soundtrack of noted German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1973 science fiction film World on a Wire, long before it was common for classic rock to be used in such a fashion.

11. Coming Your Way (from Then Play On, released September 1969). Almost all of the tracks on this fantasy compilation feature Green as singer and/or songwriter. I made an exception for a couple items from the band’s most outstanding LP, Then Play On, which was almost evenly divided between compositions by Green and Danny Kirwan. Kirwan’s “Coming Your Way” opened the album with near-tribal rhythms and snaky guitars that curled to anguished climaxes.

12. Closing My Eyes (from Then Play On, released September 1969). If only in retrospect, much of Green’s material on Then Play On hints, or downright states, his growing dissatisfaction with the superficiality of rock stardom. “Closing My Eyes” might have reflected some restless discontent, but did so with beguiling serenity, like an oasis within the storm of Peter’s newly chaotic rock-god life.

13. Showbiz Blues (from Then Play On, released September 1969). If the hints of discontent in “Closing My Eyes” were subtle, in “Showbiz Blues” they were in your face. “Tell me anybody, do you really give a damn for me?” Peter scoffs on the sparse and scary “Showbiz Blues,” with some of the most keening slide blues guitar to be heard on any recording.

14. Although the Sun Is Shining (from Then Play On, released September 1969). The second of the trio of Kirwan-penned-and-sung selections, featured some exquisitely sad guitar. Though superficially chipper, “Although the Sun Is Shining” hints at the demons that would drag Danny down and out of the music business, much as Peter was slightly before him.

15. Rattlesnake Shake (from Then Play On, released September 1969). Almost as if to consciously puncture the oft-downbeat mood of Then Play On, “Rattlesnake Shake” is an all-out exuberant rabble-rouser, more in line with the macho hard blues-rock of just-emerging British bands like Led Zeppelin and Free. They performed this on one of the relatively few surviving film clips of the Peter Green lineup on January 8, 1970, on the syndicated TV show Playboy After Dark, hosted by Hugh Hefner. That’s not as unlikely a forum as it seems; Playboy After Dark had quite a few rock star guests, including the Grateful Dead, Deep Purple, Linda Ronstadt, and Country Joe & the Fish.

16. Like Crying (from Then Play On, released September 1969). While Fleetwood Mac were usually a pretty loud and raucous electric blues band in the Peter Green era, they could also play material more in line with the rural blues that was electric blues’ direct ancestor. The third and final of the Kirwan-penned songs here is a good-time low-key near-country blues that nonetheless masks some underlying anguish.

17. Before the Beginning (from Then Play On, released September 1969). Another track that shows Green’s knack for minor-key blues, “Before the Beginning” concludes Then Play On with despondent eloquence, as if he’s making his farewell statement almost a year in advance of actually leaving the band.

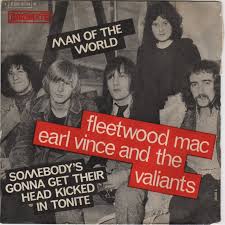

18. Man of the World (single, released April 1969). A #2 hit in the UK, “Man of the World” again showed the band stretching out beyond—even way beyond—the blues into a flowing, melodic rock that was blues in feel but not in form. Sung with grace by its writer, Peter Green, this was another song that was in retrospect an expression of his growing discontent with stardom and its phony trappings. Unlike the lyrically similar tracks on Then Play On, however, it steered clear of gloom with a relatively upbeat melody that was more pensive than sad, the laidback verses exploding into a hard rock bridge.

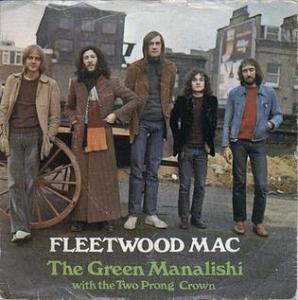

19. The Green Manalishi (With the Two Pronged Crown) (single, released May 15, 1970). One of the most unlikely Top Ten singles of the classic rock era (at least in the UK; it didn’t make the US charts), “The Green Manalishi (With the Two Pronged Crown)” was an unrelentingly ominous, grinding track with stop start-tempos and angry flurries of hard rock guitar riffs. Set against a full moon and dark night, the words were just as menacing, and at times downright fearful in their anxiety. Just after its release, Peter Green quit Fleetwood Mac, unwilling to continue in what he felt was the hypocritical music business. The music business is still hypocritical, but very few people act on their feelings and cut their ties with it at the apex of their stardom, as Green did.

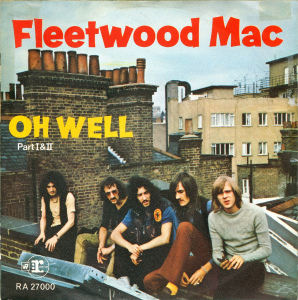

20. Oh Well (Parts One and Two) (single, released September 26, 1969). Although “The Green Manalishi” was the final Fleetwood Mac release with Peter Green, the epic “Oh Well” makes the most suitable closer. Issued as a two-part single, the first half of the song was a tense modified boogie of sorts built around a captivating circular hard-rock riff, the instrumental breaks corkscrewing to unsettling climaxes. The lyrics were certainly unusual for a big hit (as this was in the UK), Green painting a most unflattering self-portrait (“I ain’t pretty and my legs are thin”) and questioning whether one could know what anyone was thinking, even when God himself was queried.

As offbeat as this portion was, it in no way prepared listeners for the second half of “Oh Well,” which bore more resemblance to flamenco-flavored classical music than blues or rock. Purely instrumental, its mournful melody featured Green on nylon-string and electric guitars, timpani, and cello; his girlfriend Sandra Elsdon on eerie recorders; and Jeremy Spencer, finally making a useful contribution to a 1969 recording session, on elegiac piano. It could have hardly been more different than “Oh Well (Part 1),” as the first half was titled when it was used on the A-side of a single, the second part being used on the flip as “Oh Well (Part 2).” Yet the pieces complemented each other well, as if the band (and particularly Green) were finding some measure of peace after nearly getting swallowed by the storm. It was not only the peak achievement of the Peter Green era, but as fine a track as Fleetwood Mac recorded in any era, and as notable as any rock recording by anyone in the late 1960s.

In the rock history courses I teach, I periodically pause upon some figures to emphasize that they have not gotten the mainstream media coverage they deserve and are more important than most mainstream rock histories give them credit for being. Gene Vincent, Link Wray, and Sandy Denny are just a few examples. Peter Green is another. As he was just 23 when he left Fleetwood Mac, one almost weeps to consider what he and the band might have achieved had he stayed with them longer. One also almost weeps to survey the sporadic, artistically nearly negligible records he’s sporadically done since leaving Fleetwood Mac, none of which remotely approached the majesty of his best work with the group. The tracks on this imaginary CD should have been just the beginning of a lengthy string of achievements. But for reasons that still elude easy comprehension, the beginning was all there was.