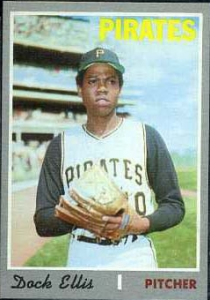

There aren’t many documentaries about individual baseball players, at least if you don’t count the ones I don’t see that probably air on cable TV. No No: A Dockumentary is a recent theatrical release, but probably won’t be seen by a whole lot of people due to its niche subject matter, detailing the life of one of the most colorful players of the 1970s, Dock Ellis. I saw it last night at the San Francisco International Film Festival, and it does a pretty good job of covering the mercurial career of a good-but-not-great pitcher who’s still most notorious for proclaiming he threw a no-hitter under the influence of LSD.

The highlights of Dock’s career – that 1970 no-hitter, his unabashed use of drugs and drink, wearing curlers in his hair on the field, getting into conflicts with the baseball establishment for his outspoken opinions on racial injustice, starting the 1971 All-Star game for the National League, and his post-baseball life as a drug counselor – are fairly well known to serious baseball fans. They’re decently Doc-umented in No No (with a good soundtrack of obscure vintage soul-funk), so this post will focus on some of the more surprising things that cropped up in my viewing.

With the passage of decades since Dock’s heyday, other players from the era are also becoming frank about the widespread drug use within the game. Fans already knew it existed after pitcher Jim Bouton wrote about the ingestion of amphetamines, known within baseball as “greenies,” in his classic Ball Four diary of the 1969 season. That was one of many things about the book that infuriated the baseball establishment, but in retrospect, it seems that if anything, Bouton might have toned down the reality of the situation. After all, he felt their benefits were limited, making you think as though you had better stuff than you did, and didn’t quite state that virtually every player used them.

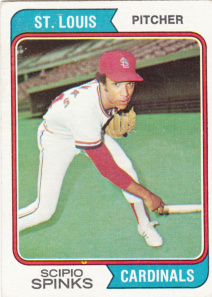

But in No No, a number of other players (and quite a few, interestingly, are interviewed throughout the film) from Dock’s time do. They even give percentages. One, pitcher Scipio Spinks (one of the great baseball names) — a very promising hurler who won just seven games in a career cut short by injury — even put the percentage of users at 95 or 96 percent. There’s been much outrage over steroid use by ballplayers (and other athletes) in the early twenty-first century, but this reminds us that the history of drug use in the sport far predates our own era, and was not just present, but prevalent.

Scipio Spinks, owner of one of professional sport’s greatest names, though not one of baseball’s greatest lifetime records (7 wins, 11 losses).

Ellis, however, was an outsize drug user even by these standards. He claimed to have even taken sixteen or seventeen pills at once. No harm done if he wasn’t a pusher, some might say; his two wives, both victims of horrifying instances of domestic abuse, would say otherwise. When he was on these substances, observes one of his spouses, “I think he thought he was taking them over, but it was the other way around” — one of the most concise, on-target summaries of drug abuse I’ve ever heard.

Despite and sometimes because of his excesses, Dock was generally beloved by his teammates, friends, and family. The early-to-mid-1970s Oakland A’s are generally remembered as the most colorful of the period’s major league teams, but this movie also reminds us that the Pittsburgh Pirates gave them a run for their money. Pitcher Bruce Kison even goes as far as to remark that Pirates hated getting traded away because it was so boring being on other teams. (For a good portrait of the young Kison – speeding to his wedding just hours after helping the Pirates beat the Baltimore Orioles in the 1971 World Series, Santana blasting on the car stereo – see the chapter on Bruce in Pat Jordan’s fine book The Suitors of Spring.)

Pat Jordan’s 1972 The Suitors of Spring collected profiles of various major and minor league players and coaches, mostly pitchers, including a young Bruce Kison.

The Pirates were also notable for not just featuring more blacks than most teams, but fielding the first all-black lineup in major league baseball history on September 1, 1971. A few of the Pirates remember the occasion in No No, one of them claiming that the Buccos fell behind 7-0 in the first inning, not even thinking about the all-black personnel as they needed all their focus to pull out a 9-7 win. That wasn’t quite how it happened: they did fall behind to the Phillies (with Ellis on the mound) 2-0 and 6-5 in the early innings, but did indeed win 10-7. And they won the World Series the next month, though Ellis was sidelined by an arm injury after losing the first game.

Not everyone was as enamored of Ellis as his fellow Pirates, all of whom (including Kison, Steve Blass, Al Oliver, Gene Clines, and Dave Cash) speak of him in glowing terms in No No. Texas Rangers catcher Jim Sundberg’s impression of Ellis when the pitcher was on other teams: “I don’t want to meet him in an alleyway.” After Ellis was traded to the Rangers, Sundberg, who did not indulge in drug use, kept their relationship strictly professional.

The mid-‘70s Cincinnati Reds probably held no great love for Dock either. In an incident almost notorious as his LSD no-hitter, he began the first inning of a May 1, 1974 game against the Big Red Machine by intentionally hitting the first three batters. Joe Morgan, it’s remembered, thought Ellis wouldn’t hit him because Morgan was a “brother.” On the mound, though, all opponents were equal, Ellis plunking Morgan when the Hall of Famer took his turn at bat. Dock went on to walk Tony Perez with the bases loaded before getting removed from the game.

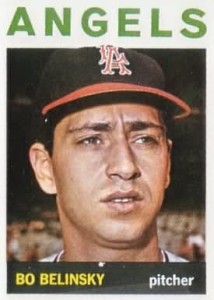

As an aside, one of the oddest things about No No is its use of clips from a way-obscure promo film of the early 1980s, Dugout. Though it’s hard to tell from the brief excerpts, it seems to have been a short designed to scare Little Leaguers away from drugs. Ellis doesn’t appear in it, but, even more unexpectedly, Bo Belinsky — another talented pitcher who threw a no-hitter early in his career — does. Unlike Ellis, Belinsky never had much other success in the big leagues, finishing with a 28-51 lifetime record. Despite that 1962 no-hitter for the Los Angeles Angels (as they were called then), Belinsky was regarded as never fulfilling his potential, largely in part not to drug use, but to being a playboy, dating Mamie Van Doren (to whom he was briefly engaged), Ann-Margret, Connie Stevens, and Tina Louise, as well as marrying Playboy Playmate of the Year Jo Collins.

From what little we see of Belinsky in the excerpts from Dugout used in No No, he seems to be warning kids away from drugs, in the wooden manner common to charismatic non-actor celebrities. The kids seem to be taking his cautions seriously, but here’s betting that no one could successfully warn aspiring big leaguers to stay away from the likes of Ann-Margret and Tina Louise. As it happens, Pat Jordan’s The Suitors of Spring also has a fascinating profile of Belinsky, who seemed to living it up just as hard right after getting out of the big leagues as he did in his brief peak.

Like Ellis, Belinsky would become a counselor (for alcohol abuse). One of Ellis’s clients, if that’s the right word, came as a surprise to me. Texas Rangers owner Brad Corbett, Sr., as his son reveals in the movie, was an alcoholic. Ellis remained friendly with Corbett after his brief time in Rangers uniform, and helped Corbett with his drink problem, Dock spending (according to at least one account in the film) almost all of his post-baseball life sober before his death in 2008.

It was a productive comeback of sorts considering how poorly Ellis, like many athletes, handled the sudden loss of his skills and end of his career. I’d forgotten that Dock briefly returned to the Pirates to finish his career at the end of 1979. The Pirates were fighting for a playoff spot (which they got, going on to win the World Series), and picked up Ellis with just a week or so to go in the season. He didn’t pitch too badly in his three games and seven innings, going four frames and getting a no-decision in the one game he did start, the second game of a September 24 doubleheader. (I’m guessing that doubleheader is probably the reason he got picked up, to make an emergency start to help out a heavily worked staff.) He confessed to Bruce Kison, however, that his arm was shot, and never appeared in a big league game after the regular schedule was over, being ineligible for the postseason roster. A five-hour session of abusing his second wife — including holding a gun in her mouth, and afterward demanding she have sex with him — was, she says in the film, fallout from his anger over getting released shortly afterward.

Lots of athletes have similarly ugly falls from grace when the cheering stops, even in a time when high salaries would seem to make post-career financial security a given. Not many athletes make something from themselves after the worst of it, as Ellis did, judging from that documentary. Which might have been the greatest saving grace of a man who, in another of the film’s surprises, received a letter of admiration from Jackie Robinson shortly before Robinson’s early-‘70s death. In many respects, Robinson was not nearly as controversial a figure; he was not a substance abuser, did not call attention to himself with antics like wearing hair curlers on the field, and even supported the Republican Party after his playing days had finished. In those ways, they weren’t kindred spirits. But in refusing to back down against a world in which racial discrimination was too prevalent, they were very much united.