It might seem relatively puny today when there are so many other sources for album reviews in print and on the Internet, but when it came out in late 1979, The Rolling Stone Record Guide was a godsend to those of us just building our music collections. Crucially, it didn’t just list and describe almost 10,000 records, but also gave them critical analysis (if often briefly in the case of most of the more minor artists) and ratings. Like many another publication rating albums, movies, books, and in these days of Yelp everything from restaurants to chiropractors, the scale went from one star (“poor”) to five stars (“indispensable”). Well, that wasn’t quite the whole range. There was also a no-star rating, represented not by a star but by a solitary square, reserved for the worst of the worst.

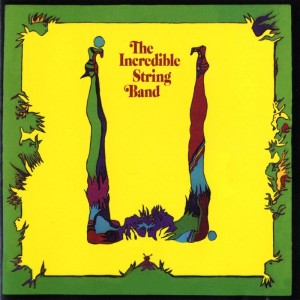

The Incredible String Band’s U—dubious recipient of the lowest rating in the original Rolling Stone Record Guide.

These bottoms of the barrel were represented by a symbol that looked like this: ◼. Just so you were in no doubt as to how they felt about those no-stars, squares, bullets, or whatever you wanted to call them, these were described as referring to albums that were “Worthless: records that need never (or should never) have been created. Reserved for the most bathetic bathwater.” Oof!

Thirty-five years later, naturally, many fans would find much to disagree with. All three albums listed by Rock and Roll Hall of Famers AC/DC get the bullet, for instance (not that this bothers me), as do some records by cult favorites like the Dictators, Wild Man Fischer, and Audience. These were also the days when rock critics weren’t as sensitive about hurting artists’ feelings, and some of the dismissals are pretty funny and withering no matter what you think about the LP. Hello People, for instance, are panned as “the ultimate evidence that mime acts should not be allowed to make records.” Sometimes they don’t even bother making fun of the turkey: Dap Sugar Willie’s entry, for instance, reads in total, “Least funny black comic alive. (Now deleted).” Does anyone remember the poor devil?

Dap Sugar Willie, dissed by the Rolling Stone Record Guide as the “least funny black comic alive,” though they rather undermined their authority by misspelling his name as Dap Sugar Willy in their entry.

Nuggets from those no-star reviews would make for entire post of their own. In this one, however, I’m going to focus on those no-star albums that I own. Yes, I do own some of them, even though some would think it’s part of my rock critic job to scare people away from such items. Now that so many years have passed, out of morbid curiosity I flicked through the volume last weekend to find out just how many resided in my collection, especially as I got a used copy in decent shape for a dollar last year. (A sound investment, as the binding on copy I got in late 1979 as a 17-year-old has long since crumbled, though I still have that too.)

I was surprised to count just four albums the guide judged “worthless” that reside in my collection. That’s not so much a testament to my good taste, or (even worse) a similarity between my tastes and those of the guide’s writers, as a reflection of the guide’s incompleteness. Even sticking to pre-1980 albums, there were many, many — thousands, at the least — LPs the guide didn’t cover, either because they were out of print or because the editors/writers simply weren’t aware of them, so many vintage rock records having yet to be discovered or analyzed. I could not guarantee, for instance, that the guide wouldn’t have given the lowest rating to some of my cult favorites, like records by Satya Sai Maitreya Kali or Savage Rose, had they been included.

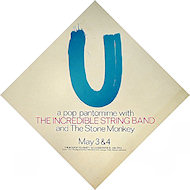

Enough excuses. What were the four records I own that they stomped on? Naturally, I think all of them have their merits, and certainly none deserve the no-star slag. Let’s start with the 1970 double album by the Incredible String Band, U. I put the front picture near the top of this post, so here’s a promo poster for variety:

Poster for some Incredible String Band live performances of U, which they attempted only a few times before lack of money and audience enthusiasm put an end to the enterprise.

Fans of albums that get savaged often accuse the reviewers of not even listening to the records. That’s probably usually not true, but I do wonder, in this case, if the critic who penned the Incredible String Band entry (Ariel Swartley) spent much time with U. Swartley liked some of the ISB’s records, particularly their second (1967’s 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion) and third (1968’s The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter), which have always been their most popular among critics. U is not specifically commented upon, though the later LPs are generally dismissed as not being on par with their earlier and better efforts.

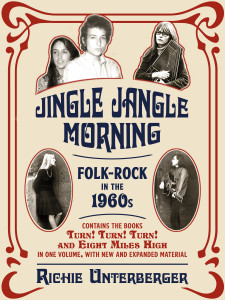

To me, however, U is undisputedly their most enjoyable album, and certainly their most diverse, though the two-LP format had much to do with that. Like some double albums, there’s some pretentious overambition at work, especially as it was in essence the soundtrack to a failed multimedia production incorporating mime, theater, and miscellaneous performance art. Here’s what I wrote in the discography to my book Jingle Jangle Morning: Folk-Rock in the 1960s:

Perhaps a double LP (now a double CD) adding up to almost two hours is too much to take even for Incredible String Band fans. Yet even though this only sprung into being as the soundtrack of sorts to the ISB’s ambitious multi-media stage production U, it was actually for the most part among the band’s most listenable material, rewarding patient admirers. While “The Juggler’s Song” had the sort of medieval minstrelsy that audiences had come to expect, this album’s more unexpected instrumental excursions with sitar and electric guitar counted among the ISB’s most far-reaching and experimental endeavors.

The ebook Jingle Jangle Morning combines the two-part 1960s folk-rock history Turn! Turn! Turn! and EIght Miles High into one volume. Besides revising, updating, and expanding the original text, it also adds a new 75,000-word bonus mini-book.

I’m not even a huge Incredible String Band, but find the no-star rating puzzling. As I do, in fact, the consensus among a number of critics that the ISB’s best albums were 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion and The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter, after which they took a long downhill ride. Even ISB producer Joe Boyd holds this view, putting much of the blame on their (as he sees it) artistic slide after the group’s conversion to Scientology. But however one views their career arc, my own view is that U isn’t that bad. In fact, it’s rather good.

Another album of mine to get the dreaded ◼ was Dan Hicks’s 1969 debut Original Recordings. This has the first released versions of some of his most famous, wittiest tunes, like “How Can I Miss You When You Won’t Go Away?,” “I Scare Myself,” “Canned Music,” and “Milk Shakin’ Mama.” Context could be key to the rough rating—again, as it happens, assigned by Ariel Swartley, who praises Hot Licks backup singers Maryann Price and Naomi Eisenberg elsewhere in the Dan Hicks entry. Price and Eisenberg, as Swartley notes, weren’t on Original Recordings, some of whose songs were cut in different versions for other releases (there’s even a recording of “How Can I Miss You When You Won’t Go Away?” by Hicks’s pre-Hot Licks band the Charlatans, though it wouldn’t come out until 1996).

But on its own terms, Original Recordings is a fine, funny, enjoyable (if somewhat low-key) twisted country swing record. There’s something of an underproduced demo feel that’s a little surprising considering it came out on a major label (Columbia subsidiary Epic). But it’s certainly not worthy of a ◼, even by hardcore fans of the Price-Eisenberg-era Hot Licks. One of the backup singers on Original Recordings, incidentally, was Sherry Snow, who’d been half of one of the most overlooked mid-‘60s Bay Area folk-rock acts, Blackburn & Snow.

The third of my four albums to get the ◼ buzzer is perhaps a more understandable target. Issued in 1975, the Rolling Stones’ Metamorphosis was a motley collection of 1960s outtakes not assembled or blessed by the band. A few such exploitative compilations of marginalia also get the ◼ rating, notably the 1973 Bob Dylan anthology Dylan. Dave Marsh (the book’s principal editor) goes as far as to warn readers away from the album, writing “a wise person would pass this up, if only out of respect for the group” (just after conceding that its cover of Chuck Berry’s “Don’t Lie to Me” is decently done).

Yet for hardcore fans—and when we’re talking about the Rolling Stones, those surely number in the hundreds of thousands—Metamorphosis is essential Stones history, and at points quite enjoyable. (Even if it does sport one of the ugliest covers ever, almost as if ABKCO was trying to frighten customers away.) Besides “Don’t Lie to Me,” “If You Let Me” is a quite nice folky outtake (variously dated by different sources to the Between the Buttons and Aftermath sessions), though it sounds a bit like a demo that didn’t get finished, a la some other Stones tracks from this period that didn’t make it onto their core UK LPs (like “Sittin’ on a Fence”). “Downtown Suzie” is a quite passable bluesy, boozy late-‘60s outtake that holds additional interest as one of the few Bill Wyman compositions recorded by the band.

On the downside, the mid-‘60s demos comprising the heart of Metamorphosis don’t even feature the whole band, with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards the only vocal and instrumental contributors. In addition, most of these are the wimpy pop tunes they gave to other artists as they were struggling to become songwriters, given most un-Stonesy overblown orchestral arrangements. For those very reasons, however, they’re also fascinating looks at their early compositional efforts, and not without their catchy moments, if hardly on par with the best early British Invasion originals (let alone their own originals once they hit their stride with “Satisfaction”).

You do have to suffer through vastly inferior versions of “Heart of Stone,” “Out of Time,” and “Memo from Turner” (the last of these a solo single for Mick Jagger when featured in the movie in which he starred, Performance), not to mention shabby annotation devoid of detail. As a final insult, the US version cut off two songs (albeit two of the flimsiest) that appeared on the UK version, cementing the feeling it was something of a ripoff. If it was a bootleg rather than an official release, however, it would be treasured for the insights it offers into little-known corners of the early Stones’ career. It certainly doesn’t deserve to be branded with a ◼, even when judged against the band’s other work. I’d sure as hell rather hear this than Steel Wheels.

It was something of a surprise that the fourth and final item from my collection to get tarred with a ◼ was included in the original edition of The Rolling Stone Record Guide at all. Pearls Before Swine were an underground cult band even at their peak, and like many such acts are far more revered now—by some critics and collectors, at least—then they were while they were around. Their precious brand of acid folk (a term not even in circulation when Pearls Before Swine started in the late 1960s) was not going to please all analysts, however. And like the Incredible String Band, they were in some ways polarizing, inspiring both fervid devotion and intense annoyance.

Bart Testa, one of the guide’s lesser-known contributors, fell in the latter camp, calling their debut One Nation Underground “a classic example of wimp aggression. Between Tom Rapp’s lisp, his rubber-band box guitars, windy eight-minute poetry lessons and kiss-off songs in Morse code, Pearls Before Swine’s debut was, and remains, a disaster.” If he really felt that strongly, you’re thinking, it’s no wonder he gave the LP a ◼.

Except he didn’t. He actually gave One Nation Underground two stars. Testa’s real wrath was reserved for Pearls Before Swine’s second album, Balaklava, on which in his estimation “Rapp drops even the pretense of constituting a rock band and starts his long groan of pretentious Muzak.”

Quite a few intense ‘60s rock collectors would be ready to shoot Testa at this point, taking almost as much umbrage as if he’d been insulting The Velvet Underground & Nico or some such classic. I’m not one of them. I’m not a big Pearls Before Swine fan.

But…it does seem out of line to call Balaklava “pretentious Muzak.” If that’s Muzak, well, bring it on the elevators I ride; it’s a hell of a lot weirder and, for weirdoes like me, a hell of a lot more listenable than the actual Muzak you hear. Testa also rather undermines his point by concluding, “This one is distinctive, anyway, in its insane compulsion to garnish liberally with sound effects”—not exactly the kind of thing you hear in real Muzak, and also precisely the kind of thing to pique adventurous listeners’ curiosity, wondering if it can be as simultaneously weird and bad as Testa proclaims.

My take is that Balaklava‘s not great, but it’s certainly rather weird, if in a fey folk-rock way, and more lyrically than musically. I might have a hard time giving it even three stars if I had to use the guide’s scale, but I certainly wouldn’t give it a ◼. And that’s not just to justify its place on my shelf, alongside a box set of Pearls Before Swine’s subsequent Reprise albums, no less. I bet Testa would have given that a double ◼◼ if he’d been allowed.

Testa won’t be alone in miffing the Pearls Before Swine cult with 35-year-old judgments. In Christgau’s Record Guide, Village Voice critic Robert Christgau relegated PBS and Tom Rapp to the “Distinctions Not Cost-Effective (Or: Who Cares?)” appendix. “I never who they/he thought they/he thought they/he were/was throwing their/his accretions/at before” was his summary, in its entirety.

Has there ever been an album that’s gotten a similarly low rating in other publication that I have in my collection? There must be some. But in the first and still best edition of The Rolling Stone Record Guide, there are just four. And somehow, if 35 years have passed—and about a dozen years have passed since I got the last of these (Baklava, I think)—I don’t think any of the other ◼s will make the cut. But I’m not getting rid of these four, either. Or that Pearls Before Swine box, even.