Sound file storage technology seems to be changing, upgrading, and taking up less space by the hour. So it might seem questionable whether we — as individuals or as a society — should be archiving vinyl record sleeves. They take up so much more room than those sound files, and the whole concept of such things taking up “space” might be forever altered if they can be stored in the “cloud” or some such thing anyway. Why hold onto what are, after all, just glorified pieces of cardboard?

Even leaving aside the issues of artwork that would be lost and whether it’s possible to create files that sound as good as the original vinyl, there’s another vital component to many LP releases that’s of great historical importance, and often entirely overlooked in these discussions. Many of them came with liner notes that contained crucial writing and information that’s often never been reprinted. Even some notes that didn’t benefit from the much deeper research available in later decades contain perspectives and criticism of great value. At the very least these should be digitized, and archives be careful not to eliminate duplicates if vinyl editions contain entirely different annotation.

The surprise winner in my choice for the vinyl release that contains the most valuable historical liner notes unlikely ever to be reprinted.

It would be impossible to list, let alone review, all the vinyl reissues from the pre-CD era that had fine liner notes. Here’s a selection of some of my favorites, however. In a good number of instances, I don’t think they were ever reprinted in CD editions (though I admit I’m not going to buy the records all over again in a different format to find out). Some are thorough artist histories; some are artist appreciations; and some are, for lack of a better description, something else.

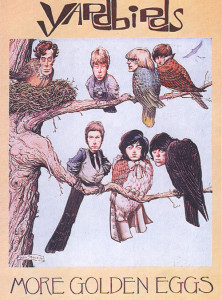

The Yardbirds, More Golden Eggs. Bootlegs usually don’t come with good notes; often they don’t come with any notes of substance. Even back in the 1970s, however, there were exceptions. In fact, I’d go out on a limb and declare this bootleg compilation of then-rare Yardbirds tracks (most have come out on official CDs) to have the most historically important liner notes that have never been reprinted anywhere, to my knowledge — and aren’t likely to, considering the unauthorized nature of this LP.

For the album came out with an extensive interview with Yardbirds lead singer Keith Relf — the longest interview he ever gave about the Yardbirds, as far as I know. Running seven pages, and covering various aspects of the band’s career, not just the songs on the LP, it was exhaustive enough for Relf to declare at the end: “You guys have given me the roughest night of my life.”

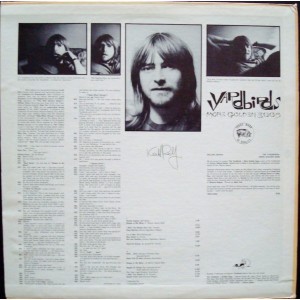

The back cover of More Golden Eggs had the first part of the interview with Yardbirds singer Keith Relf featured in the liner notes, continued on an insert inside the sleeve.

It is not exactly common practice for band members to give extensive interviews for bootlegs, and the full story was told about twenty years later in Clinton Heylin’s book Bootleg: The Secret History of the Other Recording Industry. As cover designer William Stout (who did the artwork for numerous early rock bootlegs) told Heylin, “I was really proud of the Yardbirds’ More Golden Eggs because that was the first semi-legitimate bootleg. Keith Relf of the Yardbirds was living nearby. He was just forming Armageddon, and he needed rent money. So we paid his rent that month and in return we were able to interview him and play him the bootleg record and he commented on each of the songs as they were being played…We printed the interview on the cover and as a four- or five-page insert as well, and got his signature on the cover too.”

Within a couple days of arrival at college as a 17-year-old in 1979, I happened upon a used copy of More Golden Eggs at a campus record store, in excellent condition, for the unbelievable price of $2.50. There was a catch, though — it was missing most of the interview. The first page was printed on the back cover, but the insert with the rest of it was gone. I wasn’t able to obtain a copy of the insert until almost thirty years later.

The Move, The Best of the Move. When this double LP appeared in 1974, it was early days for archival reissues of groups that never had a hit in the US, to say the least. Yet it was packaged with uncommon sense and quality, pairing the Move’s 1968 debut album with a dozen A-sides and B-sides from 1967-70. Best of all, the inner gatefold featured extensive, well-written liners by drummer Bev Bevan that commented on every song, penned in July 1973. How many other occasions were there when a member of a major ‘60s band wrote in-depth historical liner notes about his own group just a few years after the material was actually recorded? Any?

Much more recently, Bevan contributed some of the notes to another archival Move release, 2012’s Live at the Fillmore 1969. A few years ago, I heard he was shopping a proposal to write a book about the Move, but there’s no deal for that yet, as far as I know. It would be a shame if someone as obviously interested in his own band’s under-documented history wouldn’t have a chance to write a memoir before time runs out.

For all its other qualities, however, The Best of the Move did boast a cover that wasn’t exactly on par with its contents. Adorning the front was a drawing of a moving van — one of several instances when early best-of comps for British Invasion bands (like the Zombies, Animals, and Yardbirds) had artwork which illustrated the name of the artist all too literally.

Them, Them Featuring Van Morrison. It’s terribly unhip to declare this, but I’m not the biggest Lester Bangs fan. At his best he was very good, however, especially when he seemed reined in by some nominal space limitations that forced him to focus more than usual. You find this in the chapters he wrote for The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll. And he never wrote anything better than the notes he penned for this 1972 double-LP Them compilation on the London label, crammed into the inner gatefold with barely a line to spare.

It’s a masterful balance of zealous enthusiasm and sharp, disciplined description, with joking asides that are funny, not excessive. Bangs on “Gloria,” for instance: “It was the first distinct rock’n’roll classic to come from the pen of Van Morrison, and perhaps still the greatest. I mean, ‘Doctor My Eyes’ is fine and all, but it shore ain’t ‘Louie Louie.’” On Them’s cover of James Brown’s “Out of Sight”: “Its instrumental break isn’t going to give Brother JB any sleepless nights (although these days, it should).”

Unusually, Bangs comments on a number of songs that didn’t make the 20-track compilation, including such classics as “Baby Please Don’t Go,” “All For Myself,” and “Don’t Start Crying Now.” You have to dig into Phonograph Record Magazine’s coverage of Them Featuring Van Morrison to find out why, as Richard Cromelin’s review, highly unusually, included quotes about the LP and notes from Bangs himself. Regarding the track selection, he admitted, “I don’t feel real good about it. For one thing, they didn’t include ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’ and ‘Don’t You Know.’ But it’s not London’s fault. English Decca came up with the idea and the package, so don’t make it sound like I’m knocking London.”

If his quote here is to be trusted, however, his methodology for the liner note writing conformed to the Bangs legend: “They called me and asked how soon I could have the notes for them. I said tomorrow and stayed up all night and banged them out and stuck them in an envelope the next morning.”

The Velvet Underground, 1969 Live. Not all liner notes have to be historical or lengthy to be memorable. Elliott Murphy’s annotation for this double LP of great live Velvet Underground recordings is just ten paragraphs, some of them very short, taking up one column on the right-hand side of the inner gatefold. But this was a time when the Velvet Underground’s cult was just starting to take off, and their place in history just starting to get reassessed. It was unusual enough for a band that had never entered the Top 100 to get a lengthy double album of previously unreleased recordings in 1974, just four years after they’d broken up. (For the full story behind that release, read Mercury A&R guy Paul Nelson’s entertaining summary in Everything Is An Afterthought: The Life and Writings of Paul Nelson.) For an emerging singer-songwriter (as Murphy was) to trumpet the VU’s importance in no uncertain terms was no small declaration.

“It’s one hundred years from today, and everyone who is reading this is dead,” Murphy’s notes began. “You’re dead. And some kid who is taking a music course in junior high, and maybe he’s listening to the Velvet Underground because he’s got to write a report on classical rock’n’roll, and I wonder what that kid is thinking.”

Now the very notion of the Velvet Underground getting studied in 2075 or whatever would have seem absurd, even laughable, to most academics and cultural pundits in 1974. Today, it’s not so laughable. In fact, it’s already happening. As I’ve written a book on the Velvets myself, a 12-year-old actually called last year to ask me questions for a school report she was doing. And that’s no joke.

“Rock’n’roll people tend to live on the edge,” Murphy wrote. “That’s what this album is all about. Rock’n’roll has always been and still is one of the few honest things left in this world. That’s what this album is about … I hope parents will still get scared when they find their daughter listening to this music.”

Murphy was asked to do the notes by Paul Nelson, the famed rock and folk critic who was working in A&R at Mercury. “Paul’s taste was wonderfully eclectic,” Murphy explained to me. “He told me that Mercury had bought the rights to some live Velvet Underground tapes from around the same period as Loaded and invited me to come to the Mercury Studios and listen to them with him. Then he kind of offhandedly asked me if I wanted to write the liner notes for the album, which came as a big surprise. Paul made acetate copies for me to bring home. I’m still not sure why he asked me, but maybe it was because of something I said while listening to the tapes with him, something about that music lasting for 100 years.

“I knew that Lou Reed was from Long Island like me, so I was comparing myself to him and looking to his music for strength and reflecting on how rock’n’roll was both saving my life and destroying my innocence and forcing me to cut with my suburban roots. What pleases me most about my liner notes or the album is that I wrote them when I was still purely a fan; I hadn’t recorded my first album [Aquashow] yet, and knew little of the soul-splitting machinations of the music business. My ears were pure in a manner of speaking, and those notes were coming from an excitement and passion for rock’n’roll that was totally uncorrupted. It’s both a wonderful and dangerous place to be when you’re 22 years old, for you hear the glory calling and you see none of the pitfalls, of which there are many. Regardless, I knew it was the world I was determined to enter, and those notes were my calling card to get in the high gates.”

At least one member of the Velvets appreciated what Elliott had to say about the music. “I don’t even know if the band had ever heard the tapes before Paul,” Murphy told me. “But I know he was in touch with Lou Reed and eventually sent my liner notes to Lou, because a few months later Lou called my mother in New York City to speak to me. I was out and he had a nice chat with her, because when I came back to her apartment she said a nice boy named Lewis Reed had called for me.”

Brief commercial break: Murphy’s original handwritten liner notes for 1969 Live are reproduced in my book White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day.

The Easybeats, Absolute Anthology. In the early 1980s, it was enough of a miracle to find a two-LP, 43-song collection of a band that had just one hit in the US (“Friday on My Mind”), and most of whose records were almost impossible to find, particularly those that had only been issued in Australia. But to truly set it apart from the run-of-the-mill reissue, the inner gatefold had a stitched-in, LP-sized twelve-page booklet (itself a concept something that’s largely vanished in the 21st century) with an authoritative history on Australia’s biggest ‘60s band, complete with quotes from band members. (No, the quotes weren’t first-hand, but where were you going to find those back then?) In fact, it stood as pretty much the best history of the band until the 2010 book Vanda & Young: Inside Australia’s Hit Factory (University of New South Wales Press, Australia), over half of which focuses on the Easybeats, though the title emphasizes their primary songwriters Harry Vanda and George Young.

Getting back to Absolute Anthology, the liner notes also had a stupendously detailed discography before those things were common in rock reissues. It did come out on CD, and I guess there’s a good chance the liner notes were printed in that too, if in much smaller size. (As it turns out, I learned shortly after posting this that the liner notes on the CD version “are just a very basic overview; a huge disappointment compared to the LP”; see comments section.) That LP-sized stitched-in format remains neat to behold, however, and was also used on a few other reissues whose notes this post will discuss.

Gene Vincent, The Capitol Years ’56-’63. Monstrous box sets have become a fact of life these days, at least for those of us either foolish enough to spend the money on them, or clever enough to get comps. Even as recently as the mid-1980s (as recently as a good thirty years ago, in other words), they weren’t such common fare, at least in my household. They were sometimes accompanied by magisterial liner notes, such as the ones in one of the few boxes I did spring for (with store credit of course), a 10-disc UK box of Gene Vincent’s Capitol output.

For not only was there an LP-sized 36-page booklet with the kind of ridiculously detailed sessionography only the British seemed to able to summon the energy to do in those days. Icing the cake, each of the sleeves for the 12-inch discs had detailed notes on the musical contents, none of them duplicating the text found within the main booklet. That format was also used on at least one other box of a major ‘50s rock pioneer (see next entry), and it’s something not often duplicated these days, when box sets of vinyl 12-inches are still pretty rare, even with the vinyl revival of the last few years.

No doubt there were other such boxes that I missed from the late 1970s through the late 1980s, when CDs started to overtake vinyl as the dominant format in record sales. There have been yet more extensive Vincent CD boxes, and for all I know, those have yet more extensive notes. I still value this relatively “modest” vinyl counterpart, however, and more for the notes than anything else. It’s a pity that nothing Vincent recorded after 1956, however – i.e., most of this large box set – comes near the stratospheric rockabilly brilliance of his best early sides, on which Cliff Gallup played lead guitar.

Buddy Holly, The Complete Buddy Holly. It’s hard to believe that until relatively recently, there wasn’t a box set with most or all of Buddy Holly’s recordings. That meant that for many years, this 1979 six-LP package – issued at a time when major labels seldom did such things for rock artists – was coveted, even by people who’d largely stopped buying vinyl in favor of CDs. A terrific bonus was the 64-page LP-sized booklet of liner notes and photos – and, as with the Gene Vincent box detailed above, more music-specific notes on one side of each of the sleeves containing a vinyl disc. Indeed, aside from Jon Goldrosen and John Beecher’s superb biography Remembering Buddy, it’s the best source of information anywhere on Holly. Uncoincidentally, Beecher co-wrote the notes to this box as well.

Universal’s 2009 six-CD box set Not Fade Away: The Complete Studio Recordings and More filled the digital gap in Holly’s discography, and the notes in the 80-page accompanying book aren’t bad. The graphics are certainly better than those on the notes on this comparatively ancient vinyl box set. But I’m not getting rid of that vinyl box, in large part because of those notes.

Buffalo Springfield, Buffalo Springfield (1973 double-LP on Atco). Not to be confused with their self-titled debut LP, the left side of the inner gatefold of this compilation featured a basic band bio by Jean-Charles Costa. In a less frenetic manner than Lester Bangs’s Them notes, it combined some basic factual overview with passion that kept, just, from teetering over the edge into fanzine-type zeal.

There’s been lots more written about the Springfield since then that’s drawn on the much greater wealth of biographical detail that’s subsequently surfaced in books. Some is even on the generally disappointing booklet in the Buffalo Springfield box set, which at least contains a thorough list of concert dates. But it’s still great to browse Costa’s contagiously enthusiastic he-was-there praise, with such how-did-he-fit-so-many-words-into-that sentences as this description of their shows at the Whisky A Go Go:

“With Richie bouncing all over the stage on tip-toes backwards, Bruce with characteristic back to the audience pose cranking out amazing bass lines from an old warped instrument strung with four bottom E guitar strings, Neil spitting out ferocious and economical lead guitar lines, Stephen smoothing everything out with beautiful integrated harmonies and sinuous guitar, and Dewey providing the right dose of Memphis back-up funk on drums, the band meshed right away, sounding as if they’d been playing together for years.”

Or this:

“Neil Young’s ‘Mr. Soul’ stands out as the most chillingly accurate portrait of the rock-‘star’ syndrome ever put on vinyl, with lines like ‘the race of my head and my face is moving much faster’ making the listener do psychic slow takes throughout the song. Shotgun imagery, totally on target that now turns up in other people’s books as ‘found poetry’ and so far beyond a lot of the mundane flatulence that passed for ‘heavy’ lyrics in the mid-sixties that it established him in the eyes of many as the real poet of rock.”

There’s one other reason not to get rid of this anthology, and a good reason you might even want to seek it out. Though most of the well-selected tracks are easily available elsewhere, one – a nine-minute version of “Bluebird,” the last part of which is a long jam – has never appeared anywhere else.

The Merseybeats, Beat and Ballads. When Britain’sEdsel Records emerged in the early 1980s, few other labels were packaging the kind of relatively obscure ‘60s rock they did at all, let alone packaging it well. Many early Edsel releases came with a detailed four-page insert with thorough small-print artist histories and rare vintage illustrations. You really can’t fairly single one or two out for the highest praise, but I liked their fairly extensive Merseybeat series, whose liner notes (by still-active Liverpool rock historian Spencer Leigh) often drew on first-hand interviews.

Anthologies such as this one for the Merseybeats not only made the best of a band’s work widely available in LP form for the first time (certainly in the US), but also served the first true sources of hard information about many second-line British Invasion groups – not just the Merseybeats, but also the Mojos, the Artwoods, and the Creation. In the cases of some of the more mediocre Merseybeat bands like the Escorts and the Big Three, dare I say, the liner notes were much more entertaining than the music.

There have since been more extensive CD compilations for the likes of the Merseybeats and the Mojos, but the liner notes on these thirty-year-old-or-so collections remain the best. I especially like this quote in the Mojos’ Working: “When I asked one Mojo if [the name of manager Spencer] Lloyd-Mason was hyphenated, he replied, ‘Yes, and I wish the hyphen was between his head and the rest of his body.’”

Del Shannon, The Vintage Years. Sire’s extensive series of double-LP anthologies titled The Vintage Years are still fondly remembered by those who were around in the 1970s and early 1980s as among the best, and sometimes the only, way to get the most essential recordings by important hitmakers whose work wasn’t all that accessible. It’s hard to believe there was a time when that was true of the Small Faces, the Pretty Things, and the Troggs, not to mention the Nuggets compilation (originally on Elektra, and reissued by Sire). But all of them were given Vintage Years volumes. Some of the Vintage Years comps were already making it into the $3.99 and $4.99 cutout bins by the time I entered college in late 1979, making them affordable to 17-year-olds like myself. I even remember getting the Troggs and Nuggets anthologies at the small cutout bin at Urban Outfitters!

Also in the Vintage Years series were pre-British Invasion hitmakers like Duane Eddy who, although they might have had skimpier best-ofs in print, didn’t have anything with the kind of in-depth historical liner notes Sire’s writers provided. Another such entry in the Vintage Years honored Del Shannon. Maybe the CD era has seen Shannon packages with more extensive annotation, but if so, I’m not aware of any. Bomp editor Greg Shaw crammed in as much microscopic-sized text as both panels of the inner gatefold could allow, save a right-hand column with a useful discography listing all his singles (A-sides and B-sides) and LPs.

I’ve read the genesis of “Runaway” described several ways, but the way these notes tell it remains my favorite: “Nobody remembers what song they were in the midst of when Max Crook, who sometimes sat in with the band on the musitron (an odd sort of modified organ that made a sound like an electric ocarina, never failing to fascinate audiences) hit on an appealing chord sequence in the course of his solo. ‘Hit those chords again!’ commanded the singer, while the band kept up the rhythm and the people in the club looked on, bemusedly. For the next fifteen minutes, singer and musitronist worked on those chords, which were merely A-minor and G, until an entire new song had been constructed around them. Nobody there was quite sure what had happened, least of all the singer.”

The Troggs, The Vintage Years. One more cheer for the Vintage Years series, this time for the Troggs installation, written by the estimable Ken Barnes. Barnes also wrote good notes for the 1992 double-CD Archeology (1966-1978) compilation, which has a lot more tracks (52 to the “mere” 28 on Vintage Years). I still like the Vintage Years notes, however, including a rundown of each of the 28 songs, the one lyric in “The Raver” hailed as “doubtless fraught with mystic significance as regards the human condition.” Also funny are his memories as playing bass for San Jose’s “most sluggishly-rising bar band, the Savage Cabbage,” in which he’d sing “I Can’t Control Myself” in “my gruffest, toughest Reg Presley growl.”

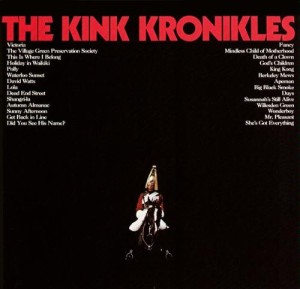

The Kinks, The Kink Kronikles. It’s hard to believe, but to quote James Brown, “there was a time” when much of the Kinks catalog wasn’t easily available. This double-LP didn’t quite wave a magic wand to instantly rectify the situation. But it was a smart combination of well-known hits (starting from “Sunny Afternoon” onward) and LP tracks with singles, B-sides, and rarities that were surprisingly hard to find in the US when this came out in 1972 (like “Dead End Street,” “Autumn Almanac,” “Mindless Child of Motherhood,” “Big Black Smoke,” “Mr. Pleasant,” “She’s Got Everything,” and “Days”). Also fine were John Mendelsohn’s notes, which crammed as much text (accompanied only by two small photos) as possible into both sides of the inner gatefold.

Mendelsohn’s observations were sharp on both musical description and the origins of the more obscure cuts. Best of all, however, was this amusing paragraph, itself worth a buck or two if you find the album these days, even if the vinyl’s trashed:

“Ray Davies, who at most times seems incapable of injuring the proverbial fly, in April, 1971, blithely reported the following to Rock’s Anne Marie Micklo, ‘I tried to stab Dave [his brother/Kink guitarist] last week. Stab him. With a knife. We were having eggs and chips after a gig and he reached over with his fork and took one of my chips and I…I could have killed him.’”

And again, let’s raise a glass to those days when one-sentence paragraphs like these escaped the editor’s pruning:

“As is the case with ‘Strangers,’ one of his two endlessly intriguing contributions to the Lola album, the literal meaning of Dave’s ‘Mindless Child of Motherhood’ is decidedly elusive – while its individual images are all so intensely personal as to be impenetrable, they add up to an enormously powerful expression of rage whose potency is greatly heightened by the fury and anguish of Dave’s strange strangled voice (which, if you hadn’t noticed, is quickly becoming as expressive an instrument as Ray’s).”

In his notes, Mendelsohn also, with refreshing candor, lamented the absence of rare B-sides like “I’m Not Like Everybody Else” and “Sittin’ On My Sofa.” The first of these (though not, oddly, the second) would soon be included on 1973’s The Great Lost Kinks Album, which combined rarities with unissued material. It is most notorious, however, for notes on a double-sided insert devoting about half their space to savage criticism of the then-current-day Kinks (who’d just left the label that issued this comp, Reprise). Those notes were by…John Mendelsohn.

Sample: “In the recent Everybody’s in Show Biz, there’s hardly a trace of my own favorite Davies, the immensely-social-conscienced champion of the forgotten ordinary people. Instead, it’s a bitchily egocentric Davies who dominates the work, one whose primary interest is making clear to his listener the agony he must endure to stay on the road entertaining us.”

Which is followed by another one-sentence paragraph special:

“To which this kronikler’s own response is: if it makes him so miserable that he can think of little but the insufferable cuisine of the motorway and how he’s compelled to consume maximum portions of same in order to retain sufficient strength to come onstage to perform for us, he certainly and we probably would be better off in the end if he’d retire from touring and get back to sensitizing us – with some of the most beautiful songs anyone’s ever written – to aspects of the world that few other writers even perceive.”

The Great Lost Kinks Album was soon unavailable, and here’s betting its liner notes have never been reprinted with commercial CDs (and never will). But now that its quite rare and fine tracks are not all that hard to find, those notes give you one more reason to snap this up should it show up in the used bin – in which case, alas, it will probably be a lot more expensive than vinyl copies of The Kink Kronikles.

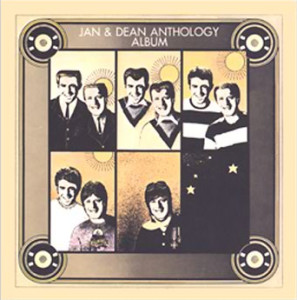

Jan & Dean, Anthology Album. For a time in the early 1970s, United Artists inaugurated a conscientious reissue program that actually gave some early rock artists double LPs with respectful packaging and lengthy stitched-in LP-sized liner notes. There were a few good entries in this series, like the ones for Eddie Cochran (with liner notes by Lenny Kaye) and Ricky Nelson. My favorite entry was the one for Jan & Dean, with liner notes by both Dean Torrence and a young Dave Marsh, then of Creem magazine.

It’s kind of hard to think of Marsh now as a more or less underground rock writer, but that’s more or less what he was at the time. And giving Jan & Dean major praise for both their music and comic talents, as Marsh does here, was not exactly the safest path to take at a time when pre-Beatles rock such as this was just starting to get taken seriously by a critics, rather than getting dismissed as childish tripe. There are also, oddly, two columns of type about Marsh himself – about the longest writer bio I remember seeing in liner notes, now that I look at it — though I couldn’t say whether that was Marsh’s decision.

Also valuable is a chart, taking up the whole right inner gatefold, of most of Jan & dean’s most notable songs, detailing not just date recorded, studio, equipment, lead vocal, label, and highest chart position, but also number of background vocal overdubs; Jan’s girlfriends at the time of each recording; Dean’s girlfriends at the time of each recording (anyone ever notice that Dean’s late-‘60s squeeze was Patty Findlater, one of the Palisades High School students profiled in the popular 1976 book What Really Happened to the Class of ’65?); Jan and Dean’s respective cars at the time each track was cut; and the number of records each tune sold (the last one, a 1968 cover of the Beach Boys’ “Vegetables,” is simply noted as “not released,” though it made its first appearance on this compilation).

Yet I must admit my favorite feature on Anthology Album is not in the liner notes. It’s talented graphic artist Dean Torrance’s cover, whose five panels present drawings of the pair as they change from crewcut teenagers to mod surfers and – poignantly, in the last one – Dean alone, Jan Berry having been sidelined by a terrible car accident.

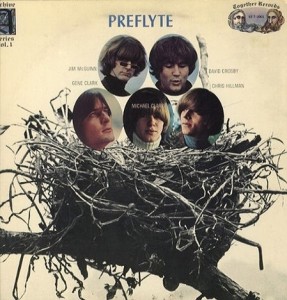

The Byrds, Preflyte. Some liner notes aren’t serious contenders for the most scholarly works or the most entertaining, feverishly enthusiastic prose, but have endearing historic value anyway. Like this one for Preflyte, a collection of fine early Byrds demos that was one of the first (the first?) serious archival collections of previously unreleased work by a major rock band. The liner notes are by someone who knew them well, publicist Billy James. He puts things in perspective as follows with honesty unusual for a ‘60s release of outtakes: “If you enjoy works in progress, if you like to watch growing things, you will like this album – but bear in mind they are work tapes only, recordings for rehearsals. Jim Dickson, who with Eddie Tickner was the Byrds’ manager and who produced these recordings and a few other things in his good time, says these are sort of like baby pictures – and it takes a while before you feel comfortable showing them.”

As it turns out, the music was not just historically interesting, but quite good on its own merits, perhaps enduring for far more years than even associates like James thought possible. Billy lapses into earnest sentimentality that gives a more personal touch to his recollections than most such annotations when he writes, “‘You Won’t Have to Cry’ really gets to me; damned if I know why. It just seems so poignant; there’s this peculiarly serious aura about the whole thing.”

Preflyte would eventually be expanded to a whopping forty tracks (from its original eleven) on a 2001 two-CD reissue, with a fifty-page booklet of historical liner notes. You still need to find the original vinyl edition (whether on its original Together label or subsequent reissue on Columbia), however, to read Billy’s notes.

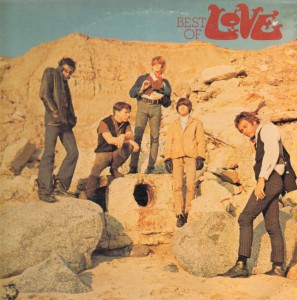

Love, Best of Love (1980 compilation on Rhino). Though it soon became the leading reissue label in the world, in its early days, Rhino usually had to squeeze all its liner notes onto the back cover. Such is the case with this early Love compilation – it’s a measure of how “early” it was in the reissue game that most of Love’s catalog was unavailable. Even by liner-notes-printed-on-the-sleeve standards, this one has teeny-tiny type, the kind that makes friends with worse vision than mine ask me to read the menu to them at restaurants.

These particular notes are not a serious contender for the Top Ten of liners from the vinyl era. Yet they’re an interesting example of how even such rather unprepossessing packages can contain text that generates its share of interest and controversy. In particular, Elektra engineer/producer Bruce Botnick states that Arthur Lee “was real unusual – on acid 24 hours a day. In fact, everybody in the band was out-of-it.” He also reveals that their 1967 classic Forever Changes “started out as a project that Neil Young and I were originally going to produce,” and that “I was prepared to record the album with Arthur singing and playing on his songs, and Bryan singing and playing on his songs, with backing by studio musicians,” two tracks being recorded that way before a shocked, crying band got it together to play on their own material.

These observations have been amplified upon and given different perspectives by other participants in the subsequent decades. But at the time, they were of great interest to Love fans, to say the least. Little information was available about the group then, and this and less controversial quotes on the sleeve from Botnick and Elektra chief Jac Holzman were part of the start in getting more knowledge about Love into circulation. It took thirty years, but eventually a 300-plus-page book about the band – John Einarson’s Forever Changes: Arthur Lee and the Book of Love – would come out, a circumstance unimaginable when this LP was issued back in 1980.

Lee himself, it should be added, offered some of his own prickly memories of the band in the notes. “We used to work every night,” he remembered. “After we started making money, the more we made, the less we worked, the less we were a unit, and Love deteriorated. People’s personal habits started to come before the music. Initially they would listen to me because I wrote 90% of the songs. After we became successful, they got big heads. Everybody had money, everybody had a house, a car, a flash Cadillac. They didn’t need me. Money spoiled them – it spoiled me too. It was a strange time. I thought I was gonna kick the bucket.”

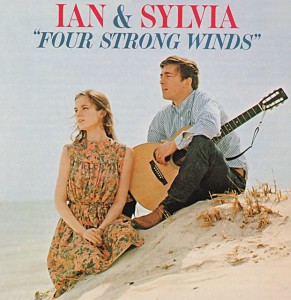

Ian & Sylvia, Four Strong Winds. Lastly, our sole entry that was not a reissue, but a contemporary LP, issued in 1964. This and several other early Ian & Sylvia albums, however, had liner notes that almost could have been for reissues, such was their scholarly detail. That sort of approach – a lengthy delineation of the origin of each song (even the original compositions), along with detailed biographical notes that read more like a newspaper article than an album sleeve – weren’t that uncommon in early-‘60s folk. But Ian & Sylvia were the king and queen of the format, Four Strong Winds in particular covering almost every inch of available space with type.

As I wrote in my book Jingle Jangle Morning: Folk-Rock in the 1960s, “The lengthy liner notes to numerous early-1960s folk releases now seem stilted and over-serious in their minute details of the multitudinous sources of these ballads, blues, and broadsides from North America and around the world, like entries in an unspoken competition for who could range over more territory than anyone else.” Looking back at such sleeves now, however, you almost feel pangs of nostalgia for the days when liner notes like these wore their influences on their sleeves, unafraid to emote with all the diligence of a master’s thesis. These days, such an approach would either be laughed at as ridiculously earnest, or mistaken for tongue-in-cheek satire. In the CD era, the innocence of such seriousness has been lost.