One of the rewards of doing research for intensely detailed books is that the deeper you dig, the more there is to find. (There certainly aren’t many financial rewards involved!) Such is the case with untangling the histories of the Velvet Underground’s associates, especially in the years before 1966, when quite a few people from the avant-garde scene influenced the path the band would take. Sometimes it leads you to experimental records and movies you never would have checked out otherwise, and even makes you aware of interesting other projects with little or nothing to do with the Velvets.

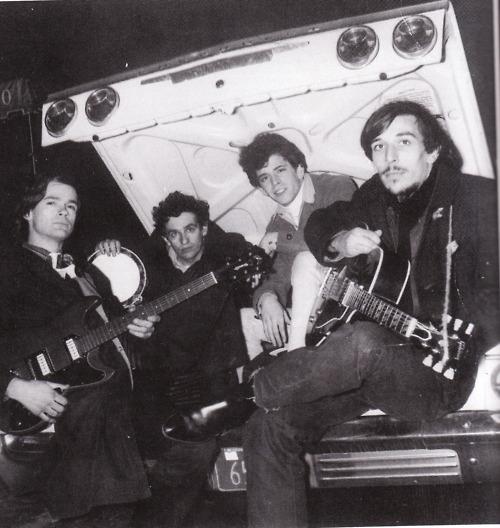

One of the more interesting people who was involved, if briefly, with future Velvet Underground members was Walter De Maria. He was the drummer in the Primitives, the group formed by Lou Reed and John Cale with another guy who wouldn’t go on to the Velvets, Tony Conrad. The band was only around for about two or three months in late 1964 and early 1965, and only Reed appears on the sole Primitives single, “The Ostrich”/“Sneaky Pete,” recorded before the other musicians were recruited. But it was in the Primitives that Reed and Cale first worked together, forming the core of the Velvet Underground after Conrad and De Maria drifted away to other pursuits.

The work of Tony Conrad is fairly well known, at least to many people with an interest in the avant-garde arts. He played in La Monte Young’s group with Cale before and (for a little while) after the Primitives and made quite a few seriously avant-garde recordings, a good number of which were made commercially available. He also made one of the more noted experimental films of the 1960s, 1966’s Flicker, comprised solely of alternating black and white frames.

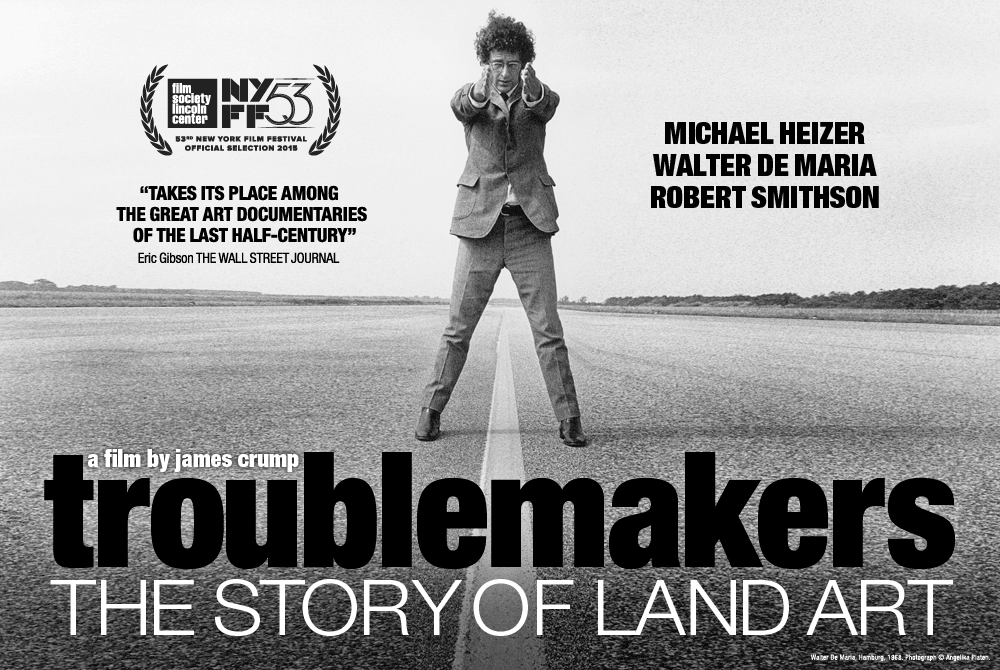

Walter De Maria’s work outside the Primitives is not so well known, at least to those whose interest in the Velvet Underground is focused on their musical manifestations. He is quite well known as an environmental installation artist, though many who know him for that work are unaware of his relatively slim activity as a musician. In fact, his 1977 piece The Lightning Field is one of the most celebrated examples of “land art,” its 400 stainless steel poles occupying a grid measuring one mile by one kilometer in New Mexico. Other noted, smaller-scale De Maria creations, New York Earth Room (a room filled with 250 cubic yards of earth) and The Broken Kilometer, have been on permanent display in New York City for many years. Some of his visual artwork can be seen, along with some footage of De Maria himself, in the 2015 documentary Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art, which is pretty interesting even if your interest in De Maria (and land art itself) is casual.

The poster for the documentary “Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art” features a photo of Walter De Maria.

While De Maria’s musical activities are relatively obscure, they’re more extensive than many people realize. Serious Velvets fans — at least those serious enough to read my book White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day — know that not long after the Primitives, he was drummer in the Insurrections, fronted by fellow avant-gardist Henry Flynt. Flynt had his own fairly close Velvets connection, filling in for John Cale at a few actual Velvet Underground shows in fall 1966.

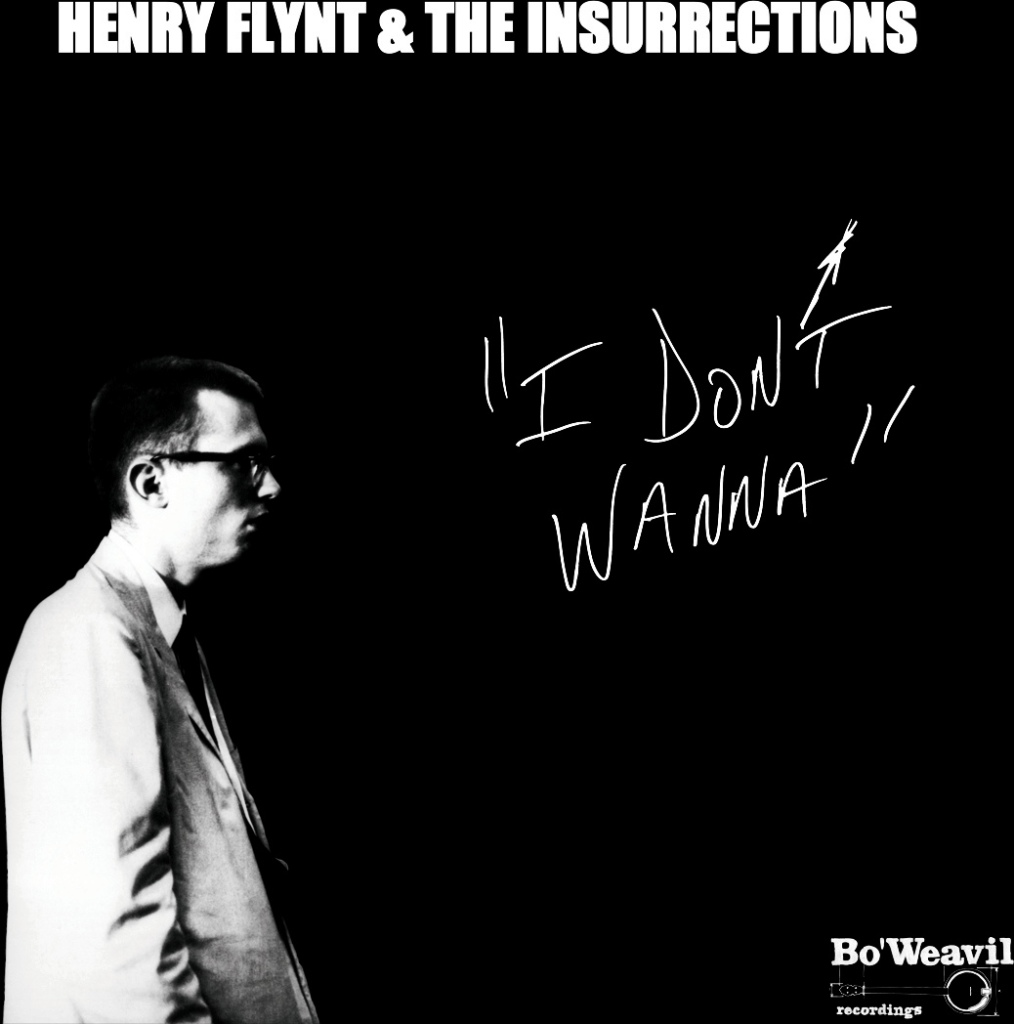

Later in 1966, Flynt recorded an album’s worth of material as the guitarist and singer in Henry Flynt & the Insurrections. The group’s raw, primitive sound is similar in some respects to the Velvets and the Fugs, but has more of a hillbilly flavor (particularly in the vocals), and is frankly not nearly as impressive as the music being produced by their Lower East Side peers. The recordings weren’t released until 2004, on the Locust Music album I Don’t Wanna.

Walter De Maria plays drums on these 1966 recordings by Henry Flynt & the Insurrections, which weren’t issued until 2004.

That’s about as far as I got on the trail of De Maria’s musical activities for the first edition of White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day, and I didn’t think there was much if anything left to exhume. It turns out, though, that De Maria had released an actual CD of 1960s recordings so obscure — at least, obscure enough to evade my detection — that I wasn’t even aware of it until working on my revised ebook edition in recent months.

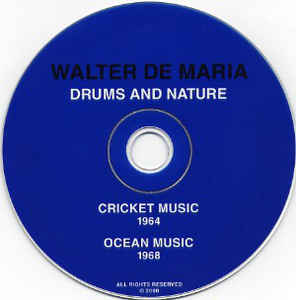

At some point in 1964, De Maria recorded a 24-minute instrumental piece, “Cricket Music.” Although the ingenious conceptual composition mixes his drumming and the sounds of crickets, their chirps are hard to detect until about the middle of this lengthy recording, on which De Maria solos in a rather jazzy, repetitious style. Soon, however, the crickets rise in volume until they’re louder than the drums, eventually dominating the soundscape as De Maria continues to plug away in the background, slightly varying his rhythms. By its conclusion, “Cricket Music” is all crickets. The entire track was eventually issued on his 2000 self-pressed CD Drums and Nature, which was reissued in 2016, though you’ll probably have a hard time finding a record store that carries it.

Drums and Nature also includes his 1968 recording “Ocean Music,” which is rather similar in conception. Starting off with several minutes of the sound of ocean waves, his 20-minute piece “Ocean Music” eventually blends the waves with his jazzy repetitious drumming, until by the end the drums have totally overwhelmed the ocean sounds. It’s thus something of a mirror image of “Cricket Music,” in which the sounds of crickets eventually submerge his drumming.

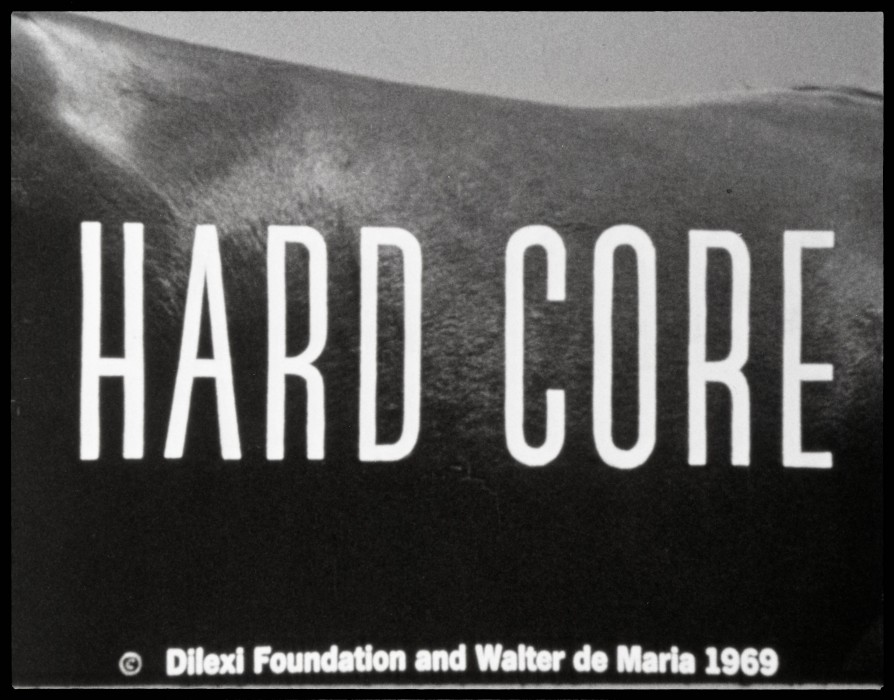

What’s more, both “Cricket Music” and “Ocean Music” were used in De Maria’s 1969 movie Hard Core, which like his other projects was hardcore avant-garde. The half-hour film’s composed primarily of slow pans over a mountain-shadowed dry, cracked lake bed in the desert. (One source says this was in the Mojave Desert; another says it was in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert.) These are periodically interrupted by super-brief shots of two cowboys preparing for a duel, ending with a lengthy shootout. That’s not quite the final sequence, however, as it’s followed by a lingering close-up of an Asian girl’s face, perhaps as an oblique reference to the war in Vietnam.

It’s not so easy to see the film these days, but it can be viewed for a $25 fee in the Film Library and Study Center of the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, California. Fortunately I live just across the Bay in San Francisco, and so was able to watch it earlier this year.

What’s most interesting to me about Hard Core is not the film — which is largely static — but that it was actually broadcast on television, and indeed made for San Francisco’s public TV station KQED, which aired it in 1969. I admit I don’t watch everything on KQED (still the biggest public TV station in the Bay Area, and indeed one of the most watched such stations in the US), but I have a hard time imagining it would screen something like this these days. Maybe there are some such items I’m missing (perhaps in their periodic broadcast of work by local independent filmmakers), but I don’t recall seeing anything close to as, well, hardcore as Hard Core.

What’s more, Hard Core was not some one-off that found its way onto KQED by a fluke, but part of its experimental Dilexi Series. This is the only installment of the series I’ve yet seen, but it also includes Frank Zappa’s Burnt Weeny Sandwich film and an episode, Music With Balls, featuring a performance by Terry Riley (himself a performer with pretty close Velvet Underground associations, collaborating with John Cale on the Church of Anthrax album shortly after Cale left the Velvets).

The twelve-part Dilexi Series was not solely devoted to music or work by filmmakers who were in, or (like De Maria) somewhat in, the musical world. There was also an episode by Andy Warhol, although his contribution, The Paul Swan Film, was (along with Burnt Weeny Sandwich) one of the two entries that had already been filmed, and wasn’t specifically produced for this series. Other installments were contributed by top photographer Robert Frank (later to direct the legendary unreleased documentary of the Rolling Stones’ 1972 US tour) and the Living Theater’s Julian Beck. Episodes featuring and/or directed by less celebrated artists encompassed dance, found footage, documentary, and satire.

Incidentally, there’s another connection between this series and a top rock band. It was produced by John Coney, and Jim Farber worked on it as a production assistant. In April 1970, Coney and Farber would co-produce an hour-long film of a Pink Floyd concert (performed at the Fillmore in San Francisco, though not in front of an audience) that was subsequently broadcast on KQED. Most, though not all, of that footage is on a DVD/Blu-Ray disc in Pink Floyd’s recent box set The Early Years 1965-1972.

Even considering the Pacific Film Archive allows you to view up to two hours of material (appointment needed in advance) from its library for the $25 fee — something, unfortunately, I wasn’t aware of when I reserved Hard Core for screening — you’d need three sessions, and $75, to see all dozen episodes. The Dilexi Series seems historically important enough to issue on DVD, or even to re-broadcast on KQED, should the station have the rights to do so. My guess is that some or most of the installments, like Hard Core, are not terribly accessible, and in some respects tough going to watch. They’d serve as a reminder, however, of the risks television can take, and the exposure it can give to important talents far outside the mainstream.