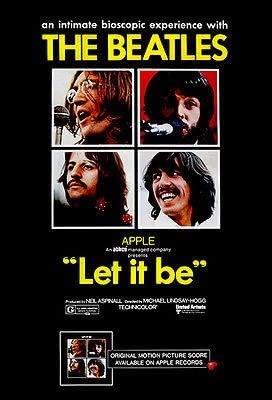

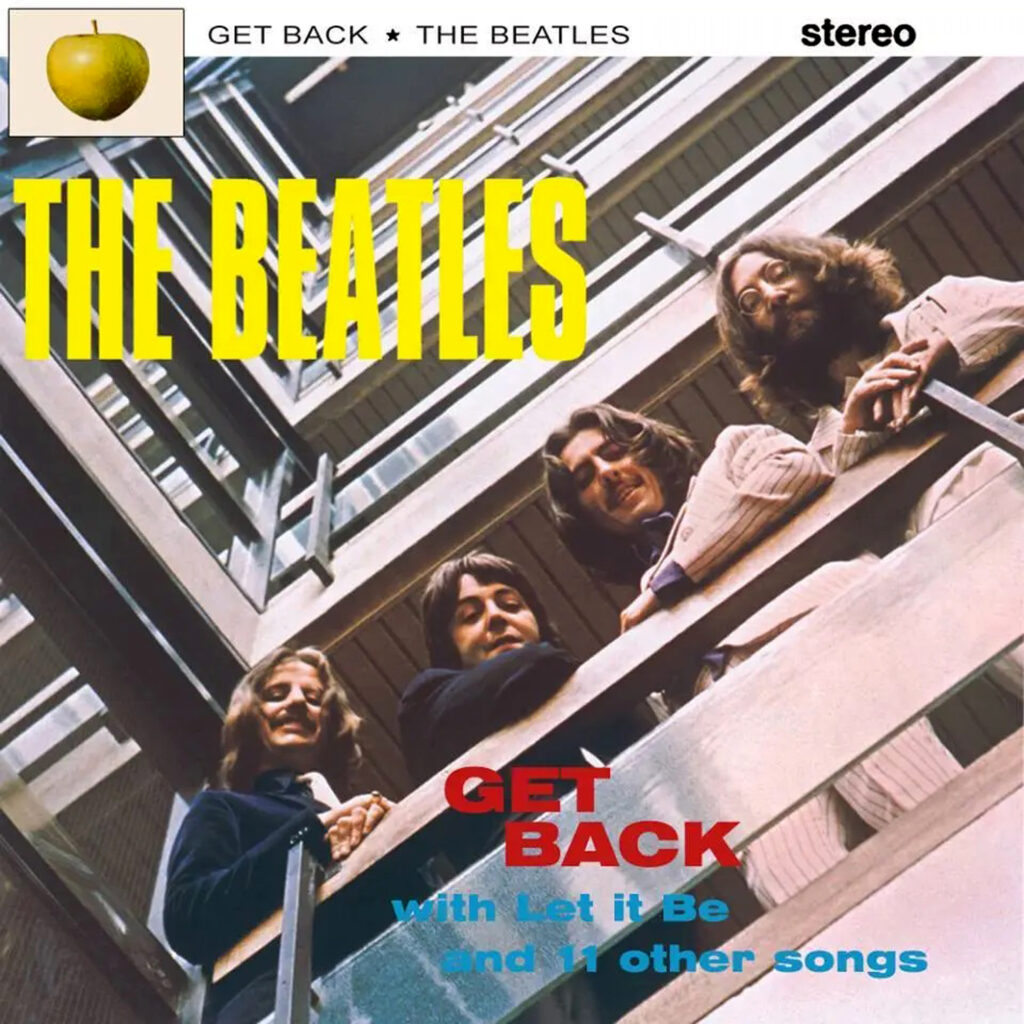

Peter Jackson’s Get Back documentary has been widely and deservedly acclaimed for the eight hours or so of footage it presents, with some context, of the Beatles’ January 1969 sessions. Footage taken during this month provided the basis for both the Let It Be movie and album, though the LP in particular didn’t come out quite as originally intended, or even as originally recorded.

This story has been told in many books and quite a few articles and films, if never in quite so much depth. Although not nearly as well known as the Get Back film (or even many other Beatles books), much of the music and dialogue from the many hours of existing recordings is aptly described and summarized in Doug Sulpy and Ray Schweighardt’s mid-1990s book Get Back: The Unauthorized Chronicle of the Beatles’ ” Let It Be” Disaster. Even that book, however, couldn’t capture some of the glances, silent shots, and atmosphere revealed by Get Back’s footage.

This post isn’t going to try to summarize all of the interesting and important points and questions raised by what the Beatles were doing in January 1969. It isn’t even going to address all of the interesting points and questions raised by the material in the Get Back film. That would take more books, and this is just a blogpost. Having heard and thought about all of this for many years (and written about the 100 or so hours of music recorded by the group that month in a section of my book The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film), I’m just going to highlight some interesting things the documentary brought to light. Even if I’ve come across some of them in the past and didn’t remember all of them when watching the film (twice), I’ll still include them, if they’re of interest for other Beatles fans.

Like the film, I’m going in chronological order, separated by date:

January 2

As many fans know by now, in May 1968 the Beatles recorded a version of John Lennon’s song “Child of Nature” at George Harrison’s home. Along with many other demos from that session, it’s now available as one of the discs in the super deluxe edition of The White Album. It’s also well known that the song was reworked, with the same melody but entirely different lyrics, as “Jealous Guy” on Lennon’s 1971 album Imagine.

John was still thinking of having the Beatles record it as they ran through possible material at the Get Back sessions. It seems, however, that he had changed the title, though nothing else major about the composition. He was now calling it “On the Road to Marrakesh.” Sitting on the fence, it’s titled “On the Road to Marrakesh/Child of Nature” when the title and composing credit is flashed onscreen during Get Back, as it is for many of the songs performed in the film.

And as many who’ve collected Get Back-era bootlegs must have noticed, songwriting credits have now officially been assigned to the unreleased original numbers performed in January, even the ones that are improvisations, fragments, or mere scraps. Many of these are too insubstantial to merit official release, but you can see the details as the end credits roll for each of the three episodes. They’re also often (but not always) flashed onscreen when they’re performed in scenes in the documentary.

January 3

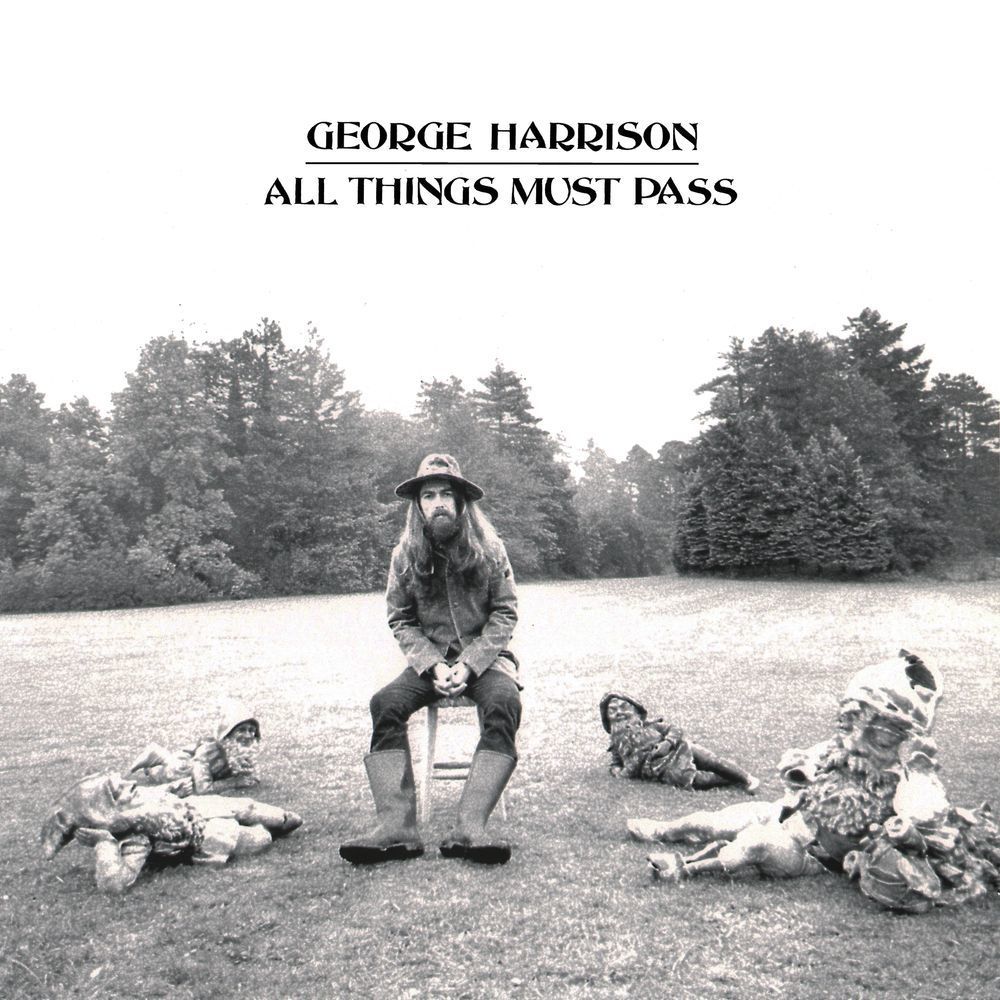

George Harrison on the compositions he’s offering for the Get Back project: “They’re all slow-ish. There are a couple I can do live with no backing.” He might have already been wondering if any would be deemed suitable by the group for the concert they were planning, where the thinking seemed to be tilted toward uptempo material. He might have been weighing whether he could do slow numbers like “Hear Me Lord” solo, though as it happened those and some others (like, most famously, “All Things Must Pass”) wouldn’t get released until his 1970 All Things Must Pass album.

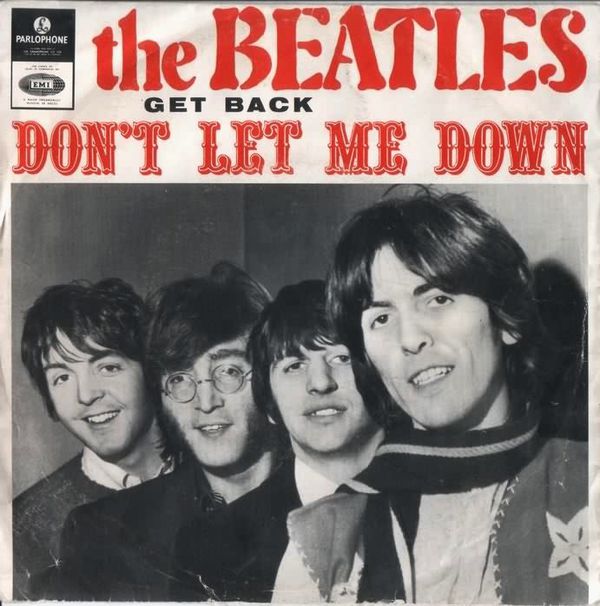

Yoko is usually pretty immobile as she sits in on most of the sessions, even on the most energetic tunes, or one that’s obviously inspired by her, “Don’t Let Me Down.” She does animatedly move at some unexpected times, dancing to the early Lennon-McCartney number “Because I Love You So,” which like most of the early pre-recording contract compositions played at the sessions were doleful and unmemorable.

As “Gimme Some Truth” is played, a subtitle reads “John suggests an unfinished song that he and Paul have been working on.” That in turn suggests that Lennon and McCartney collaborated to at least a slight degree on this song, although it was credited to John alone when it appeared on Imagine. Paul does sing a part of it, indicating he might already have been familiar with the song from doing some work on it. In the larger picture, if this was the case, it suggests the Lennon-McCartney songwriting partnership wasn’t entirely dead by this time, as some accounts would have it.

John and Paul have been accused, probably with some merit, of to some degree undervaluing or even ignoring some of George’s songwriting efforts. Several sequences demonstrate, however, that they weren’t entirely uninterested or unsupportive of Harrison’s work. In an early run-through of “All Things Must Pass,” John suggests a minor change to the lyric, modifying “A wind can blow those clouds away” to “my mind can blow those clouds away.” “Okay,” George responds. John adds: “A little bit of psychedelia in it, you know. Social comment, like.”

George offers some surprising comments about The White Album, a record that’s often considered to have contained the first major seeds of the Beatles splitting and going their separate ways. “That was the good thing about the last album,” he tells Paul. “It’s the only album, so far, I tried to get involved with. It should be where if you write a song, I feel as though I wrote it, and vice versa.” This isn’t just intriguing because it’s a more positive view of the record than has usually been attributed to the Beatles. It also makes you wonder if George felt left out or relatively uninvolved with every record before The White Album, of which there were quite a few.

Another surprise from George: thinking that the Beatles could do some of their older songs for their proposed live concert, he says, “I’ll tell you which is a good one,” and plays a very brief excerpt of “Every Little Thing.” That’s one of the more, and maybe one of the most obscure, early Lennon-McCartney songs, heard on their fourth album, 1964’s Beatles for Sale. As they never played it in concert and George didn’t write it—and it wasn’t a single or even among their more popular LP tracks, although it’s good—it’s a pretty left-field pick out of the hat.

George talks about Eric Clapton’s guitar style for a bit: “He’s very good at improvising and keeping it going, which I’m not good at.” That fits very much with what Klaus Voormann, who met the Beatles in Hamburg in 1960 and remained good friends with George (and played bass on All Things Must Pass), told me in a 2021 interview: “That’s something that Eric says too. He says George is fantastic solo guitar player. He works out his little solos. It takes him a lot of time to do get it down, he’s not free on a guitar like an Eric, who can play around anytime. He plays a different solo each time. That’s not George. He composes a little song, and that’s his solo. And that’s a fantastic attitude, which I really like.”

It’s only the second day of sessions, but George enthuses at length about Billy Preston: “The best jazz band I saw was Ray Charles’s band…Billy Preston is too much. Billy plays piano with the band. Then he does his own spot where he sings and dances and plays organ solo…then Ray Charles comes on. He’s better than Ray Charles, really. Because he’s like too much. Because he plays organ so great. Ray Charles doesn’t bother with the organ now. He just, ‘I’ll leave it to the young guy, Billy.’ It’s too much.” This is a good nineteen days before Preston visits Apple and almost instantly joins the Beatles for the next ten days or so of sessions. It’s doubtful that Harrison already specifically had Preston in mind for this, but certainly demonstrates he was familiar with his contemporary work quite a bit before Billy turned up and made a major impact on the Get Back project.

January 6

It’s only the third day of sessions (they took the weekend off), but George is already moaning about the upcoming concert. Always the least enthusiastic of the group about the Get Back project, he thinks “we should forget the whole idea of a show.” Maybe the Beatles should have never embarked upon this if he was putting such a wet blanket on the idea so early on. Perhaps it was fueled by a feeling that it was rushed and ill-conceived, as he remarks at another point on this day, “We’ve only run through about four [songs, for a show planned in only about a dozen days]. We haven’t learned any at all.”

January 7

Paul says “we should do the show in a place we’re not allowed to do it. Like we should trespass, go in, set up, and then get moved, and that should be the show.” He suggests the House of Parliament as a possibility of a place where they’d “get forcibly ejected, still trying to play numbers, and the police lifting us.” Although it would be on the Apple rooftop, this is remarkably close to what actually happened on January 30, though the police wouldn’t use such force to stop the show.

Although Let It Be director Michael Lindsay-Hogg would help suggest the rooftop location, he thinks Paul’s idea of trespassing would be too dangerous. He suggests hospitals and orphanages as alternatives. John doesn’t seemed inclined to give Lindsay-Hogg’s notions serious consideration, saying he doesn’t think orphanages and police balls are going to do it.

In his typically buoyant, optimistic mood, George says “the Beatles have been in doldrums for at least a year”—this four days after he told Paul the White Album was the first one he really felt involved with. “I don’t wanna do any of my songs on the show,” he declares, which couldn’t have elevated spirits. He even suggests a divorce, which he’d come close to initiating by quitting the band for a few days on January 10.

It looks like a recording, maybe an acetate, of “Across the Universe” is brought on to be played to the Beatles. Although a version had been recorded by the group in February 1968, it had yet to be released. As he didn’t have too many of his own new compositions for the proposed upcoming concert/album, John was looking toward things he’d written quite a while ago (like “Child of Nature”) but hadn’t yet released with the Beatles as possibilities. Although the Beatles had done a version a little less than a year ago, it seems like they and John in particular have forgotten the lyrics, hence the recording being played to them.

January 8

George brings “I Me Mine” in for consideration, reporting that he wrote the song the previous night, its rhythm inspired by a waltz he saw on TV as part of a ceremony. His sour comments from yesterday on the whole prospect of doing his songs or the show itself to the contrary, he proposes “I Me Mine” for the concert “because it’s so simple to do,” though they wouldn’t do it (or any Harrison compositions) on the roof. In fact, although “I Me Mine” would be on Let It Be, that version wouldn’t be recorded until early January 1970, and then by the Beatles without John Lennon.

Although he’s not the biggest insider in the Beatles’ circle, Michael Lindsay-Hogg sees Lennon and McCartney aren’t getting along as well or working together as much. “Paul and you are not getting on as well as you did,” he tells John.

Paul confronts John about his lack of new material: “Haven’t you written anything else? Haven’t you? We’re gonna be faced with a crisis,” thinking of the show they’re supposed to be doing of all-new songs in about ten days. Although Paul has the image of the most diplomatic of the Beatles and one who wants to avoid confrontation in favor of amiable discussion, in fact he was probably the one person most likely to challenge John when necessary.

George, never too gung-ho on the concert in the first place, is making his feelings uncomfortably public: “I just want to get it over with.” He also seems worried about the expense involved, pointing out they haven’t even made back the cost of the film used for Magical Mystery Tour, another endeavor in which he half-heartedly participated.

Ringo doesn’t say much during the January sessions, but tells Michael Lindsay-Hogg “we’ve been getting grumpy for the last 18 months.” That goes back to just after Sgt. Pepper, indicating the tensions eventually pulling the group apart have been brewing for quite a while.

January 9

Linda Eastman, who’ll marry Paul in a couple months, tells Lindsay-Hogg “I feel the most relaxed around Ringo.” “Me too,” Lindsay-Hogg responds. The inference here is that she and Lindsay-Hogg don’t feel as relaxed, or too relaxed overall, around John and George.

Paul infers here and elsewhere that the lead vocal on “Carry That Weight” is meant for Ringo, as he works on it on piano with Starr watching. He refers to it as a comedy or story song, and fills in a verse between choruses with scatting, Ringo singing along with the chorus. The verse, he says, will have lyrics about getting in trouble with the wife and getting drunk. The vision will have changed by the time it’s recorded for Abbey Road and welded to “Golden Slumbers,” with only the chorus surviving, sung not by Ringo on lead, but by all four Beatles in unison.

George is seen on drums briefly, probably just fooling around instead of intending to sub for Ringo if necessary, as Paul did on a few Beatles recordings.

Yoko again gets animated at an unexpected point, bobbing enthusiastically to a song (really a jam) the Beatles didn’t release, “Commonwealth.”

Yoko and Linda are seen (though not heard) chatting together in a quite friendly fashion, though they don’t have the public reputation of being friendly or getting along.

The Beatles work on one of the best of the many instrumental jams (most of which are dull and/or cacophonous) they play this month, “The Palace of the King of the Birds.” A different section plays over the end credits to episode one of Get Back, and while it might sound to viewers like incidental music specifically recorded for this documentary (especially since no information flashes on the screen as to what’s playing), it’s a genuine January 1969 Beatles recording. Rather than being the sluggish blues many of their jams are, it has a haunting, elegiac tone, spotlighting organ rather than guitar.

John’s honest and rather flippant about his lack of new material, remarking “I’ve done all of mine, both of mine.” If he’s just counting two songs, he might be referring to “Don’t Let Me Down” and “I’ve Got a Feeling” (which incorporates his “Everybody Had a Hard Year” composition with the bulk of the song, which was written by Paul), though “Dig a Pony” had been tentatively played a couple times, and he’d revisited some songs he’d written earlier that had been passed over for release on Beatles records, like “Across the Universe” and “Child of Nature.”

January 10

On the day George quits the band for about five days, there’s a hint of his touchiness when he tells the others as they work on a guitar part, “You need Eric Clapton.” John and Paul hasten to tell him, “You need George Harrison.” Ultimately Harrison isn’t mollified, walking out in the middle of what was supposed to be a full day’s work.

John offhandedly suggests replacing George with Eric Clapton, perhaps out of anger with Harrison or trying to brush off the seriousness of the crisis. Remember, however, that Lennon had recently played with Clapton as part of the one-off lineup (with Keith Richards on bass and Mitch Mitchell on drums) with which he performed “Yer Blues” on The Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus in early December 1968.

Michael Lindsay-Hogg asks John if anyone’s quit like George has. “Well…Ringo,” Lennon admits. Although it wasn’t public knowledge, Ringo had quit for about ten days the previous summer during the sessions for The White Album.

Lindsay-Hogg talks about the weakening Lennon-McCartney partnership with longtime Beatles assistant Neil Aspinall and producer George Martin. “John and Paul aren’t writing together much anymore, are they, really?” he notes. They were collaborating more than has sometimes been reported, but more in the sense of refining some of the other’s songs than actively writing together. George Martin realizes this, commenting that “nevertheless, they’re still a team.”

John, Paul, and Ringo briefly hug each other as the day’s work ends after George quits. This is one of the most crucial shots in Get Back. It illustrates their camaraderie and concern for each other at a moment of crisis in a way that doesn’t come across at all without the visuals when you’re listening to the audio bootlegs of the sessions, where they often discuss their troubles flippantly.

January 13

It’s the day after a group meeting that didn’t work out well, George walking out. As Paul, Linda, Lindsay-Hogg, and others talk in a group before John’s arrival, it’s evident they feel freer to discuss Yoko’s impact on the Beatles than they do when he and she are around. Linda says of the previous day’s group meeting, “She was talking for John, and I don’t think he really believed any of that.” Acknowledges Paul, for John “if it came to a push between Yoko and the Beatles, it’s Yoko.” Asks Lindsay-Hogg, “Were you writing together much more before she came around?” “Oh yeah,” McCartney responds.

Yet in the same conversation, Paul expresses much more sympathy toward the couple and positive vibes toward Yoko than he’s usually credited with. “She’s great, she really is alright,” he says. “They just want to be near each other.”

When John doesn’t show up or answer his phone, Paul seems to verge on choking up into tears – a moment that doesn’t come through, or certainly with anywhere near the same impact, on the audio tapes. “And then there were two,” he laments, though he’s informed that John wants to speak to him on the phone before a possible breakdown. Note John wants to speak to him, not Ringo or both Paul and Ringo, intimating these are the two guys ultimately calling the shots for the Beatles.

After John does arrive, signaling he’s willing to continue as part of the Beatles, he and Paul have a serious conversation in the cafeteria. Michael Lindsay-Hogg sensed something was up, and in his memoir Luck and Circumstance: A Coming of Age in Hollywood, New York, and Points Beyond remembers asking “our soundman to bug the flower pot on the lunch table.” According to a story in Sound & Vision on the making of Let It Be and how the footage was used in Get Back, this was done on both January 10, the day Harrison quit, and January 13.

Readers are all poised for the big revelation as to what was said and what went down on January 10 when Lindsay-Hogg dryly notes, “My bug had only picked up the sounds of cutlery banging on china plates, obscuring what the muffled voices had said.” Fortunately, twenty-first century technology enabled dialogue from the January 13 conversation to be retrieved for a scene in Get Back, where Lennon and McCartney talked over the crisis with more grave honesty than they seemed to have done in group settings.

There are too many points made in that conversation to recap in total in a post like this, and they’re not all about how George is feeling and trying to get him to rejoin, though that’s the most urgent issue discussed. Here are a couple of the most interesting samples. John tells Paul, “There was a period when none of us could say anything about your arrangements, ’cause you would reject it all…A lot of the times you were right, and a lot of the times you were wrong. Same as we all are.” Paul tells John, “You have always been boss. I’ve always been secondary boss. Now I’ve been sort of secondary boss. Always.”

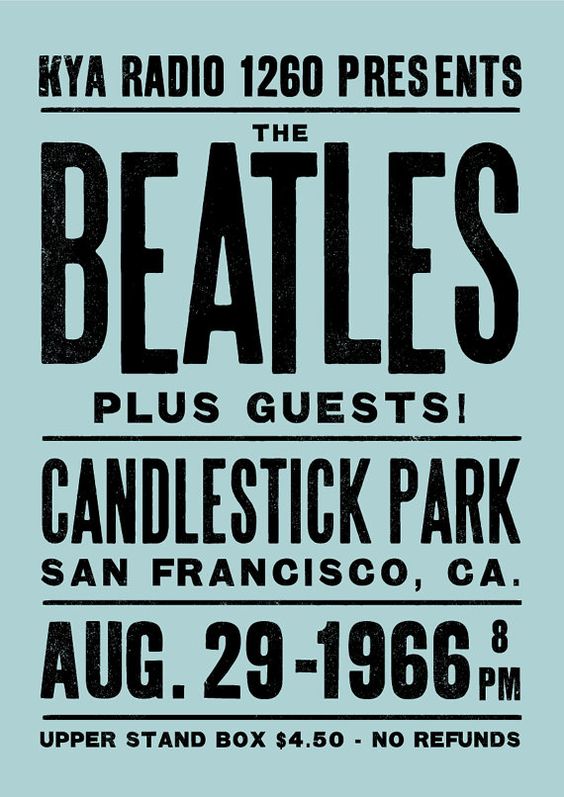

As the Beatles minus George leave for the day amid uncertainty as to whether the group will continue, Paul leaves his bass as kind of collateral for his intention to return tomorrow. “What greater faith could man have than to leave his list,” he says, referring to a setlist taped to his bass. It’s the setlist from the Beatles’ final tour, of the US in summer 1966, though it wouldn’t end up being their final performance of all.

January 14

As the Beatles struggle through rehearsals without George, Paul at one point utters, “Aimless rambling amongst the canyons of your mind.” This seems to refer to a song by the Bonzo Dog Band, “Canyons of Your Mind,” from their 1968 LP The Doughnut in Granny’s Greenhouse. Paul would have been pretty familiar with this fine British comedy rock group as they appeared in Magical Mystery Tour, and McCartney had produced their 1968 UK hit “I’m the Urban Spaceman.”

There seems to be confusion about how many songs should be played for their concert (should it take place), or are ready to be played. The numbers eleven, twelve, and fourteen are all thrown out. John mentions a “choice of six.”

Perhaps unsure of whether the Beatles have enough for an album and/or concert, George Martin darkly jokes that Ringo can do a long drum break, though Starr was known for abhorring drum solos. “An hour and a half,” Ringo adds in similar gallows humor.

January 16

George Harrison’s rejoined the band after a productive group meeting on January 15, and checks out Apple’s new studio with engineer Glyn Johns (eventually credited as co-producer on the Let It Be LP). They’re unhappy with the equipment, the studio having legendarily been designed by Apple’s supposed electronics wizard, Magic Alex Mardas, though it doesn’t perform even the most basic of functions. This gets a little trainspotter-ish, but this is different than how it’s reported in Mark Lewisohn’s excellent 1988 book The Beatles Recording Sessions. Technical engineer Dave Harries (seen in a few Get Back scenes) told Lewisohn the Beatles “actually tried a session on this desk, they did a take, but when they played back the tape it was all hum and hiss. Terrible. The Beatles walked out, that was the end of it.”

From the way it’s presented in Get Back, it seems like the whole group might not have tried a take, and maybe Harrison and Johns did the basic determination that different equipment need to be moved into Apple. The story on the making of Let It Be in Sound & Vision, however, indicates there might have been a tryout session of sorts around January 17. As that article reports, “It took a day for Harries to get the system functional enough to make a recording, at which time the band did try to make a recording with it. ‘We did one take,’ says Harries. ‘They didn’t like it, and they just walked out, without saying a word. Then we got the word to bring our stuff in'” from EMI.

January 21

Beatles road manager/personal assistant Mal Evans shows a prototype of an instrument “Magic Alex” Mardas has invented to John. “It’s a combination of a bass and rhythm guitar with a revolving neck,” Evans tells Lennon. It’s not known whether the Beatles had a use or desire for this, or if it evolved into a finished product.

John and George stage a mock fight in Apple Studios, laughing and smiling. Much tension in the group’s obviously gone now that George has rejoined.

George opens a package of LPs including Smokey Robinson & the Miracles’ Greatest Hits and Make It Happen. Although he’s not usually regarded as the biggest soul fan in the Beatles, he was getting back into rock and soul again after a couple years or so of concentrating more on Indian music. On the second day of the sessions, he’d sung lead on a fairly spirited if casual version of a Motown hit, Marvin Gaye’s “Hitch Hike.”

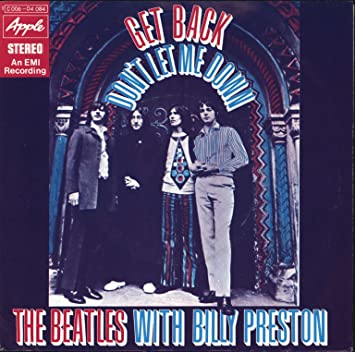

At one point during the day, a list is presented of songs that seem to be under the most consideration for the upcoming show, if that was to take place. These were “All I Want Is You” (a working title for “I Dig a Pony”), “The Long and Winding Road,” “Bathroom Window” (a working title for “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window”), “Let It Be,” “Across the Universe,” “Get Back to Where You Once Belonged” (a title later shortened of course to “Get Back”), “Two of Us (On Our Way Home)” (eventually simply titled “Two of Us”), “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” “I’ve Got a Feeling,” “Sunrise” (an odd alternate title for “All Things Must Pass”), and “I Me Mine.” Eight of these would eventually get on the Let It Be LP, and two others find a spot on Abbey Road, with “All Things Must Pass” waiting until Harrison’s 1970 album of the same name.

It’s strange, however, that the aforementioned list doesn’t include “Don’t Let Me Down,” which had already been extensively worked on, and would be part of the January 30 rooftop concert and the B-side of “Get Back,” though it didn’t make the Let It Be album. As to why “Across the Universe” seemed to drift out of the picture the rest of January, on the 23rd Harrison asked Lennon about whether the song would be used for the Get Back project. “No,” John responded, “‘cause it’s going out on an EP.” That seems to confirm he and/or the Beatles were planning an EP, as has been reported elsewhere, with “Across the Universe” and the four songs exclusive to the Yellow Submarine soundtrack. That EP never materialized, and a new version of “Across the Universe” did ultimately resurface as part of the Let It Be album, though not for another year or so, when Phil Spector did post-production on the Beatles’ 1968 recording of the song.

The Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet LP is seen near John as the Beatles play. Maybe Lennon’s keeping up with the competition. It wasn’t a brand-new release, but was pretty recent, having come out on December 6, 1968.

Ringo’s seen playing bass on “Hi Heel Sneakers,” a rare and possibly unique glimpse of him playing the instrument with the Beatles, though he’s likely just fooling around with it briefly.

During a version of “Don’t Let Me Down,” John throws in references to Dicky Murdoch. This was a British comedian who wouldn’t be known to US audiences.

George says at one point, “We just need one more in the group,” in seeming acknowledgement of how their determination to record live without overdubs is leaving some gaps in the arrangements. He doesn’t specifically mention Billy Preston, but that’s probably in his mind when Billy visits the following day and is quickly invited to play keyboards on the sessions.

January 22

The Beatles were considering several locations for a live concert, despite George Harrison’s continued reluctance to do one, in part because of Lindsay-Hogg’s continued pressure to find an exotic setting. Amphitheaters in foreign countries and ocean liners were considered (probably far more seriously by Lindsay-Hogg than the Beatles), but another isn’t mentioned as much – Primrose Hill in London. That idea was abandoned when it wasn’t available.

John enthuses about watching Fleetwood Mac on TV, at a point where the group had some hit records in Britain, but weren’t too well known in the US. “The lead singer’s great,” he says, probably referring to Peter Green, the band’s most prominent guitarist/singer/songwriter in their early blues-rock days. “ He sings very quiet, he’s not a shouter.” Paul says they’re like Canned Heat; John says they’re better than Canned Heat. Certainly the influence of Fleetwood Mac’s then-current UK instrumental hit “Albatross” (which would reach #1 on February 1) is heard on “Sun King,” which the Beatles played in rudimentary instrumental versions during the Get Back sessions, though it wouldn’t be fully developed until it was recorded for Abbey Road.

This is the day Billy Preston starts playing on the sessions, making a significant impact on the Get Back project for the rest of the month. It’s noted in the Get Back documentary that he used to ask them to play “A Taste of Honey” when he met them in Hamburg back in 1962, when he was with Little Richard’s group. Maybe that was an influence in having the Beatles include “A Taste of Honey” on their first album, not recorded until early 1963.

Although George seems to have been the most active member in getting Billy into the studio, John’s quickly on board with Preston’s participation, telling him, “You’re giving us a lift, Bill…He’s the guy, and that solves a lot.”

John proposes, “We could do half here, and the other half outside.” That’s pretty much what happens—about half the material in strong consideration for the record is performed on the roof (and sometimes used on official releases), and about half is recorded in the studio.

“It will be the third Beatles movie,” John says of the film-in-progress. The Beatles owe United Artists one more movie (after A Hard Day’s Night and Help!), and maybe John sees this as a way to fulfill their contract. “And it will be a movie, you know, not a TV show,” he adds for emphasis. For that it probably has to be a theatrical release, not a TV show — which is also what eventually happens.

It’s only a week before the concert, but John says “we almost know three numbers, actually.” Obviously they’ve been working on a lot more than three songs, but maybe he feels only three are really down cold enough to do in live performance.

Beatles assistant Peter Brown tells John Lennon Allen Klein’s arriving in a couple days. So obviously Lennon knew Klein wanted to talk with him and the Beatles in advance of their first meeting on January 27, though the impression’s sometimes given in historical accounts that the meeting occurred more spontaneously.

At one point in Get Back, early Beatles manager Allan Williams is briefly seen at the day’s sessions. He’s not identified in the documentary, though he is in the companion book. What was he doing there? It’s not explained, though I’m guessing he was just dropping in for a visit. He was their pseudo-manager of sorts from around mid-1960 to some time in 1961 before Brian Epstein entered the picture, though he didn’t seem to have much direct contact with them after the Beatles moved from Liverpool to London in 1963.

January 23

Part of the group does what’s titled a “Freakout Jam” with Yoko Ono on vocals, the songwriter credits given to Ono, Lennon, and McCartney. “I’d like it to be part of our new LP,” recommends Lennon, and it’s hard to tell whether he’s joking or serious. Certainly it never gets seriously considered for inclusion.

George Martin’s role in these sessions is kind of uncertain. As Lewisohn writes in The Beatles Recording Sessions, “He was there for some sessions but not for others,” with engineer Glyn Johns seeming to sometimes take a producer role as well. Martin hasn’t been too positive in his memories of the sessions, feeling the group were falling apart and doing too many takes in search of the perfect live performance. On this date, however, he seems pleased with their progress, perhaps as a result of Preston having given them a life. “You’re working so well together now, let’s keep it going,” he advises them.

George Harrison unexpectedly sings a bit of the Four Tops’ 1966 chart-topping classic “Reach Out I’ll Be There” as they’re working on “Get Back.” “That’s what the song needs, it needs a catchy riff,” he feels. “Get Back” already had catchy riffs. Maybe the Beatles were making sure to be tolerant of all of his suggestions after his sensitivity to some criticism led to his brief walkout earlier in the month.

It’s only four months since it made #1, but George has to be reminded that “Hey Jude” was their last single. I don’t see this so much as a reflection of lack of interest in their output as evidence that members of big groups don’t pay as much attention to the chronology of events as many fans do. Lennon and McCartney would mix up the sequence of some of the Beatles’ album releases in subsequent interviews. “Which album is this?” asked Harrison with puzzled earnestness when he, Paul, Ringo, and George Martin were filmed listening to a take of “Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight” for the bonus disc of the Anthology DVD.

January 24

John, the most impulsive Beatle (as will also be seen by his over-the-moon enlistment of Allen Klein as his manager after his first meeting with him on January 27), seems to infer Billy Preston should join the group when he announces, “I’d like a fifth Beatle…I mean, I’d just like him in our band, actually.” Paul, the more cautious and practical one, feels “it’s bad enough with four.”

The original idea behind the Get Back sessions was to play live as a band with no overdubs. About three weeks into the sessions, it’s becoming apparent that they’re reconsidering allowing for at least some flexibility. For “Child of Nature” aka “On the Road to Marrakesh,” John reveals, “I was gonna do a big ‘30s orchestra bit.” When he reworked it into “Jealous Guy” for Imagine, he would in fact use a lushly orchestrated arrangement. At another point, he says, “After we can stick it on,” meaning do overdubbing. “It’s cheating,” points out Glyn Johns. “Well, I’m a cheat,” John shrugs.

Maybe mulling over how the Beatles have to alter their usual lineup when they’re playing without overdubs, McCartney observes, “I quite like those ones where there isn’t a bass. We’ve done a few. ‘I’ll Follow the Sun.’” When he’s on keyboards on the sessions, however, John will sometimes take over on bass (most noticeably on “The Long and Winding Road”), though he doesn’t seem to have a good aptitude for the instrument.

George suggests putting “Two of Us” “on the B-side,” though it’s hard to telling if it’s a passing half-joke. John chips in, “Release it in Italy only, let’s just make a different single for every country.” Probably he wasn’t serious, but the Beatles were entertaining some odd and highly unusual ideas in the early Apple days, and it’s not out of the question that they would have considered this before some impracticalities or difficulties in enacting such a policy were pointed out to them.

As George plays slide guitar on “Her Majesty,” John jests, “That’s the cheapest one. If gets any good on it, we’ll get him a good one.” George would get good on slide guitar, but only after seriously applying himself to the technique for his 1970 solo album All Things Must Pass.

Ringo plays “Teddy Boy” with a towel on his drums. Even when I had the Kum Back bootleg as an eight-year-old in 1970, I thought the drums on this sounded kind of like hoofbeats, and this could explain part of that.

January 25

John remarks, “I don’t regret anything ever…not even Bob Wooler.” Bob Wooler was a DJ and MC at the Cavern Club in Liverpool, and had done a lot to help advance the Beatles’ career in the early 1960s. On June 18, 1963, at Paul’s 21st birthday party in Liverpool, Lennon viciously beat up Wooler after the DJ suggested John and Brian Epstein, who’d recently taken a holiday together in Spain, might have had a homosexual affair. This incident got the Beatles some of their first, and unwelcome, publicity in the mainstream British news media. Although Lennon did send a telegram of apology to Wooler afterward, this offhand remark shows a more callous side of John than has usually been attributed to him, at a time he was starting to remake his public image over into one of a man of peace.

George Martin, in what might have been one of the rehearsals where the Beatles were trying his patience by doing take after take, is seen lying on the floor reading a newspaper. Yet although Martin, as previously noted, might not have been as directly involved with or enthusiastic about the Get Back sessions as virtually all of the others he produced for the Beatles, he was still doing some hands-on-work as a producer. He’s shown inserting a newspaper (maybe the same one he was reading) into a piano to give the instrument a honky-tonk “tack” sound on “For Your Blue.”

Michael Lindsay-Hogg and Glyn Johns, according to the Get Back documentary, are the ones who suggest to Paul the idea of doing a concert on the roof of the Beatles’ Apple building. Paul and Ringo go up with Lindsay-Hogg to check it out. Sometimes the concert has been characterized as an impulsive decision that day or the day before, but this shows the idea germinating a good five days beforehand.

Art dealer Robert Fraser is shown visiting the session on this date. Fraser was a friend to members of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. When Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were busted for what most would consider very minor drug offenses at the Redlands home of Richards in February 1967, Fraser was also caught in the raid. Although Jagger and Richards had sentences overturned after spending very brief periods in jail, Fraser wasn’t as fortunate, in part because he was charged with the more serious offense of heroin possession. He served a sentence of six months hard labor, which he would have finished only about a year before he was filmed with the Beatles on this date.

January 26

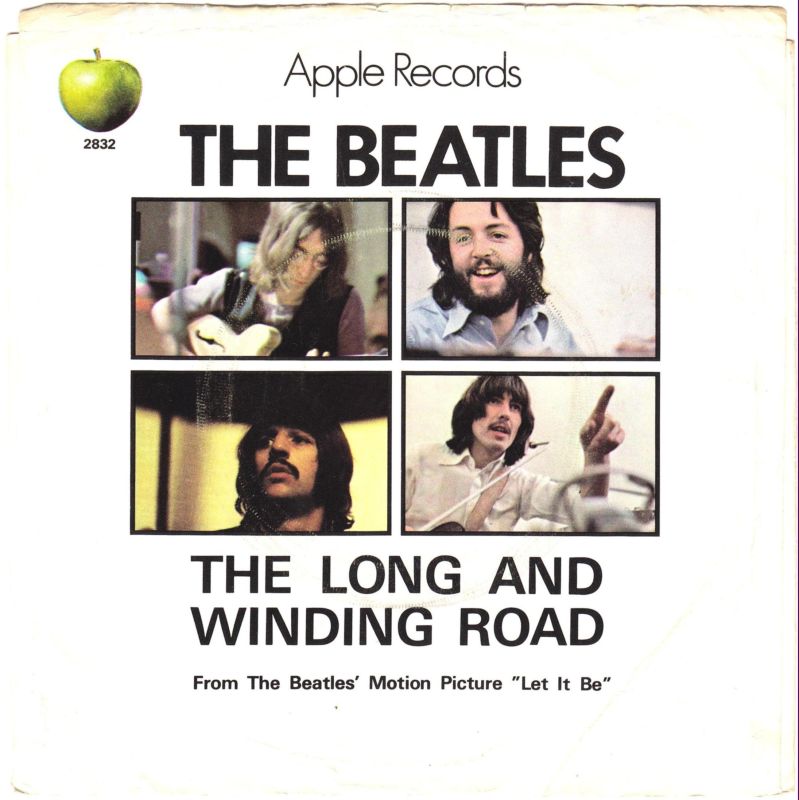

In early spring 1970, Paul would quit the Beatles, in part because Phil Spector added orchestration and female voices to “The Long and Winding Road.” McCartney strongly asserted he hadn’t approved of these overdubs, telling the Evening Standard, “I was sent a remixed version of my song ‘The Long and Winding Road,’ with harps, horns, an orchestra and women’s choir added. No one had asked me what I thought. I couldn’t believe it. I would never have female voices on a Beatles record.” George Martin backed him up on this, telling Melody Maker, “John insisted that it was going to be a natural album, a live album, and he didn’t want any of the faking, any of the Pepper stuff, any production. … When the record came out, I got a hell of a shock. I knew nothing about it, and neither did Paul. All the lush, un-Beatle-like orchestrations with harps and choirs in the background—it was so contrary to what John asked for in the first place.”

However, one of the most interesting exchanges in Get Back indicates McCartney and Martin were at least considering orchestrating “The Long and Winding Road” back in January 1969, more than a year prior to Spector’s overdubs. George Martin says, “Paul’s thinking of having strings anyway.” George Harrison asks Paul, “Are you gonna have strings?” Paul replies, “Dunno.” Continues Martin, “It needs something a little more clinical.” Paul says he heard it in his head with “Ray Charles backing,” elaborating, “We were planning to do it anyway, with a couple numbers, just have a bit of brass, a bit of strings.”

January 27

George introduces a song he’s written the night before, “Old Brown Shoe,” which he enthusiastically describes as “happy, a rocker,” maybe feeling like he should come up with something upbeat and uptempo that’s more suitable for a concert than the more reflective, slower numbers he’s recently composed. He plays it on the piano, an instrument he doesn’t play nearly as much as John or Paul. “It’s great on the piano, because I don’’ know anything about it,” he explains. “It’s great, because I wouldn’t have been able to do that on the guitar.” Billy Preston plays guitar on some of the run-throughs, although he’s mostly known as a keyboardist. Although Paul (and John) have been criticized for not paying as much attention to George’s songs as their own, McCartney seems delightedly enthusiastic as he plays along with Harrison when George starts routining the number.

More indications Paul might not be wholly satisfied with the plain no-overdubs arrangement of “The Long and Winding Road” when he remarks, “I can’t sort of think of how to do this one at all…mind’s a blank.”

More evidence that George Martin sometimes took a conventional hands-on production role at the sessions when he tells the group, “Your speakers are very near to your mics, and they’re being picked up. So you get howl round…Why don’t you have the piano open for a start?” He does so in the tactful, gentlemanly helpful manner he’s usually remembered as bringing to his work with the Beatles. “I’ll fix you, lads, I’ll fix you,” he calmly reassures them at one point.

John expresses frustrations with playing bass: “I can’t even tell if I’m in tune or not. I’ll just have to guess what I’m playing.”

George Martin expresses frustrations with the Beatles’ endless-take-perfectionism as they try to get the best live performance: “Let’s all rehearse it well, and let’s just do one take, and that’ll be it. And we’ll do it again…and do it again…and do it again.”

The Sound & Vision article on the making of Let It Be, incidentally, offers some more insights into Martin’s overall role at the sessions. “I was booked by Paul to engineer it, to be the recording engineer,” Glyn Johns told the publication. “And I expected, therefore, George Martin to be producing. And, in fact, that wasn’t the case at all. He appeared on occasion, but he wasn’t involved with the production of the music at all. I was a bit embarrassed by the whole situation, because he wasn’t involved. But he was charming, and he put me at ease, and was lovely about it.” Adds cameraman Les Parrott in the story, “He was such a subtle gentleman. I never saw him telling Glyn what to do.”

In the same piece, George Martin’s son Giles offers his take: “Glyn was the constant. He was the young engineer, sort of producer, who’s there the whole time. My dad was told he wasn’t needed. I actually went through this with Paul once. They were essentially doing a live record. They’re doing a live show, they’re not doing a ‘record.’ Why would your A & R record producer come down to your rehearsal room? But he did appear. And when he appeared, interestingly enough, they did play more songs on the days he was there than when he wasn’t. And he had a pen and a pad. And the necessity arose for some organization, because it became so chaotic, in the fact that they hadn’t really done anything, he appears more and says, ‘Okay, listen, what are you actually doing here? What’s the idea?'”

January 28

John voices a more sympathetic ear to Harrison’s material than he’s often credited with: “I’m trying to get us to do one of George’s for the first batch.” Although none of George’s songs would be done on the rooftop, where, after all, they only performed five numbers (sometimes in multiple versions) in all.

John and Yoko have met with Allen Klein for the first time the previous evening, talking with him until two in the morning. He’s already enthusiastic, in retrospective over-enthusiastic, about Klein, telling George, “He knows everything about everything…He’s gonna look after me, whatever…He knows me as much as you do.”

Yoko says Klein “owns half of MGM.” This sounds like a wild exaggeration Klein might have made to her and John. According to Fred Goodman’s biography of Klein, Klein bought 160,000 shares in MGM. To bear with a long-winded explanation for a moment, according to Isadore Barmash’s book Welcome to Our Conglomerate—You’re Fired, when Kirk Kerkorian bid for a million MGM shares in July 1968, that would have given him 17% ownership. That works out to about six million total shares. Klein’s 160,000 shares would have worked out to about 2.7% of that.

At his meeting with Klein, Klein told John that the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus would be made into an LP and a book. The book wouldn’t appear; the LP (and its associated TV special) wouldn’t be available until 1995. Klein also told Lennon the LP would be issued “to buy food for Biafra.” If there were serious intentions to make it such a charitable project, they certainly weren’t realized.

Getting back to the music, John’s still talking about “On the Road to Marrakesh” and “Mean Mr. Mustard” as possibilities for the Get Back project. As noted earlier, “On the Road to Marrakesh” would be reworked into “Jealous Guy” on Imagine, and “Mean Mr. Mustard” wait until Abbey Road.

The lineup’s varied in interesting ways as they continue to work on “Old Brown Shoe.” At one point Billy Preston’s on guitar and Paul’s not there – most likely just doing something else for a bit, not out of a lack of interest in participating, since he played along so enthusiastically on January 27. At another point Preston takes over piano from George while Harrison just does vocals.

When George introduces his work-in-progress (and eventually most famous composition) “Something,” contrary to John and Paul’s reputation for not putting much effort into George’s songs, they give him a good deal of support and encouragement. Suggests John to George, who’s stuck on devising some lyrics, “Just say what comes into your head each time. Attracts me like a ‘cauliflower.’ Until you get the word!”

John, George, and Billy briefly fool around with a stylophone, a small instrument that looks like a toy. It’s most known for being used prominently on David Bowie’s first hit later in 1969, “Space Oddity.”

There’s a shot of Linda Eastman at a keyboard at one point while the Beatles are rehearsing. It’s not certain whether she’s trying to play along, but interesting in light of how she’d join Wings as a keyboardist in a couple years or so.

Onscreen text notes the Beatles have their first group meeting with Allen Klein on this date. However, they weren’t filmed there, and it’s not discussed in any of Get Back’s scenes.

January 29

Ringo accurately says the Beatles will do five or six numbers on the rooftop show planned for tomorrow; they’ll do five (though multiple versions of several of those five songs).

Glyn Johns, who’s had some interactions with Allen Klein since Klein has handled business affairs for the Rolling Stones and Johns has often worked on recordings for the Stones as an engineer, characterizes Klein as “very strange. Very clever.” John brushes aside this possible caution with “we’re all hustlers.” Ringo calls Klein “a conman who’s on our side for a change. All those other con men are on the other side.”

Johns seems to be trying to warn Lennon about Klein without getting on Lennon’s bad side, consider how animatedly John’s raving about Klein.

“He’ll ask you a question, and you’re halfway through answering it, and if he doesn’t like the answer or it’s not really what he wanted to hear, he’ll change the subject, right in the middle of a sentence,” Johns notes. “That bugs me a bit, actually.” In hindsight Lennon would have done well to pay more heed to Johns’s observations, given how John, George, and Ringo would eventually get dissatisfied with Klein and initiate a break with him in 1973.

Just a day before the rooftop concert, there’s a lot of back-and-forth uncertainty about doing a show or how they should do it. Paul seems to be getting cold feet. Although John concedes “we’re not ready to do fourteen” songs, he adds, “I think we’d be daft to not do it,” pointing out they’d need another month of work to be ready to do fourteen. Paul feels that “we’re not doing a payoff.” John urges seizing the moment: “We’ve only got the seven. Let’s do seven. We haven’t got time to do fourteen.” George, as always the keenest to wrap things up and move on, says they could already “make half a dozen films” with all the footage they have. Glyn Johns suggests doing the rooftop concert, and then the TV show later, maybe thinking a more polished performance could be filmed for television if they’re not satisfied with the rooftop show. Michael Lindsay-Hogg gripes that “there’s no story yet,” concerned the film he’s been working so hard on will be anticlimactic.

Paul’s frustrations with recent sessions come out: “I really feel like I’m trying to produce the Beatles, and I know it’s hopeless.” George Martin, the Beatles’ official producer, is right behind him as he says this; it’s not clear whether McCartney knows Martin’s there, or whether Martin’s hurt by the remark.

George again seems to put the whole enterprise in danger by complaining, “I don’t wanna go on the roof.” Ringo, who has by far the least to say of any of the Beatles this month, might come to the rescue by simply chiming in, quietly but firmly, “I would like to go on the roof.” John quickly adds, “Yes, I’d like to go on the roof.” Maybe Ringo did the most to rescue the plan, his opinion perhaps carrying more weight at that moment precisely because he was making his voice known at a time when he said little. This could be a point at which Ringo truly did “Carry That Weight” when it seemed in danger of being dropped.

A list is shown that seems to be of the most serious contenders for inclusion in the movie, whether filmed on the roof or in the studio: “I’ve Got a Feeling,” “Don’t Let Me Down,” “Get Back,” “I’d Like a Love That’s Right (Old Brown Shoe),” “The Long and Winding Road,” “Let It Be,” “For You Blue,” “Two of Us,” “All I Want Is You,” (indistinct), “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” “One After 909,” “Bathroom Window,” “Teddy Boy,” “Dig It.” Of course a few of these wouldn’t make either the Let It Be film or LP, though “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window” would be on Abbey Road, “Teddy Boy” on McCartney’s first album, and “Old Brown Shoe” on the B-side of “The Ballad of John and Yoko.” It’s interesting to see “I’d Like a Love That’s Right” as a working title for “Old Brown Shoe,” though the opening line of that song would actually be “I want a love that’s right.”

George Martin might not have been satisfied with these sessions in retrospect, but he declares “there’s no question we’ve got an album.” It wouldn’t come out until May 1970, and Martin would only be credited as a co-producer, with Glyn Johns and someone who wasn’t even there for these January 1969 sessions, Phil Spector.

George Harrison says “I’d like to do an album of songs” on his own, as “it would be nice, mainly to get ‘em all out of the way…to hear what all mine are like all together.” Although he knows he could give away some of the songs to other artists to do, as he’d done for Jackie Lomax in 1968 with “Sour Milk Sea” and would even consider doing for Joe Cocker with “Something,” he adds, “I’m just gonna do me for a bit.” However, he wouldn’t start the sessions for his first proper solo album, All Things Must Pass, until spring 1970.

Mike McCartney, Paul’s younger brother, is shown pretending to play a piano. In a November 2021 interview with me, he remembered, “I bought this bright orange shiny leather jacket, and I simply wanted to show it to our kid [Paul] and the boys.” Going to Apple Studios as a recording session was in progress, “I slipped in, closed the door quietly, and just stood at the back, and enjoyed ‘Get Back,’ a smash hit.

“Then suddenly I realized there’s a track right down the middle of the studio. There’s a big movie camera on it, and it started to come down towards me. God, how ridiculous – this is gonna see me at the back standing here in me lovely leather jacket. I’ve gotta do something. There was a piano on the right-hand side there, and this track went to the side of the piano. So I thought, well, I’ll get behind that and they’ll think I’m playing the piano.

“And it started to keep going. All the Beatles are playing, Billy Preston is playing on his organ on the left-hand side, I’m on the right. I’m thinking, it’s getting very near my piano, which had its lid closed. It was all last minute. I thought, Jesus, I better pretend to play the closed-lid piano and look as though I’m part of the group. It went right past me, so I had to be serious, playing the piano.

“I’ve been telling people that story all my life. I’ve asked Apple many times, Mike Lindsay-Hogg, and no one’s even acknowledged it. And the next thing is our kid said, ‘Oh, you’re in this film.’ ‘Am I? Oh? I wonder if it’s my bit.’ Then Peter Jackson’s right-hand lady says, ‘I’ll send you a photograph.’ There is me at the piano in me leather jacket. So I can now prove I’m part of that track.” (The story for which I interviewed Mike McCartney, about the new book of his photos Mike McCartney’s Early Liverpool, can be read at https://pleasekillme.com/mike-mccartney/.)

January 30

Apple building doorman Jimmy Clark has a bigger and more colorful role than you’d expect as the police enter the premises to halt the proceedings. “They lock the door when they’re recording,” he blithely tells the cops as he stalls for time. “‘Cause other people keep trying to get on the roof.”