Throughout rock history, songwriters who are star recording artists in their own right have always “given” songs away to other acts. Or, at least, other acts have often recorded compositions that the songwriters haven’t released themselves, whether the composers directly gifted the songs to them or not. The Beatles famously gave away some Lennon-McCartney tunes to others, especially other people managed by Brian Epstein, and especially early in their careers. But many other stars did this too, maybe more during the British Invasion than some other periods, though this was happening and still happens all over the world.

Assembling a list of all the interesting instances when this occurred would fill up a book. I don’t have time to write that, unless someone pays me well to do so. However, I can offer some of my favorites from rock’s early years, along with some such items that might not have been great tunes, but have interesting stories behind them. I’m sure I’ve forgotten some, including maybe some of your favorites. Keep in mind this isn’t meant to be a definitive or comprehensive list, just a group of some I want to blog about.

I also didn’t want to get into the nuances of ranking them in order. So I’ll go kind of in chronological sequence, listing the artist and then the composer, or the artist and the group from which the composers came.

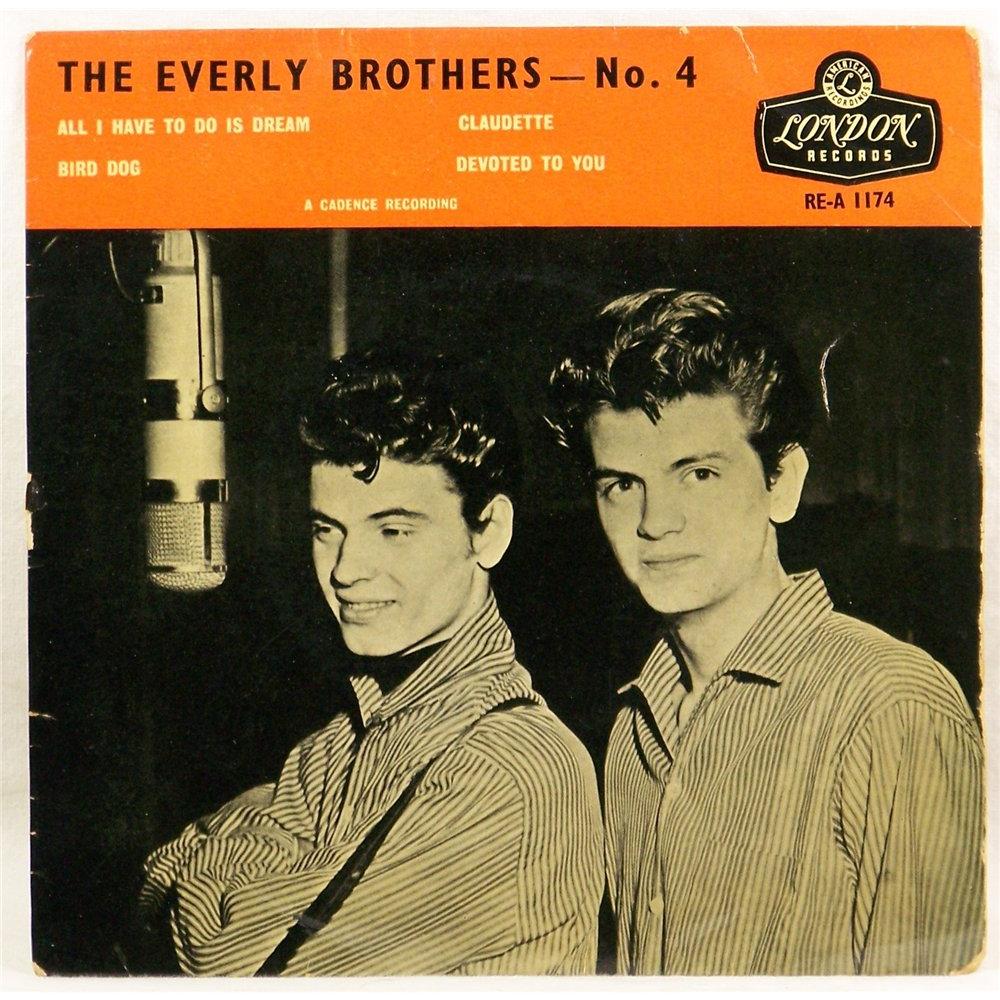

The Everly Brothers/Roy Orbison, “Claudette.” Orbison didn’t get his first big hit until 1960 with “Only the Lonely,” though he’d made some fair rockabilly records starting in the mid-1950s, usually for Sun. Perhaps not unreasonably considering his early lack of major success, he considered concentrating on songwriting rather than performing. His one major triumph in landing a hit with someone else was this 1958 B-side to the chart-topping “All I Have to Do Is Dream.”

“Claudette,” a much harder-rocking number that verged on rockabilly, was a pretty substantial hit in its own right, reaching #30. Inspired by Orbison’s first wife Claudette, it had furiously scrubbed chords and a chorus with much different, more irregular rhythms than the fairly conventional verses. The Everlys put their usual high-powered infectious harmonies into the performance. Orbison eventually recorded his own version on his 1965 album There Is Only One Roy Orbison, but the Everlys’ remained definitive.

This is the only 1950s entry on this list, and I’m aware there are others. Maybe the most famous is Buddy Holly’s “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore,” written by Paul Anka, and a pretty big hit. But I don’t think it’s a great song, and a worrisome indication that Holly might have gotten into tamer orchestrated pop arrangements had he survived. As an interesting side note, however, Holly had written a song with Bob Montgomery (“Wishing”) in hopes that the Everlys would record it. They didn’t, but fortunately Buddy cut a version (not released until 1963, with posthumous overdubbing) that’s among his best recordings, though it’s not too well known.

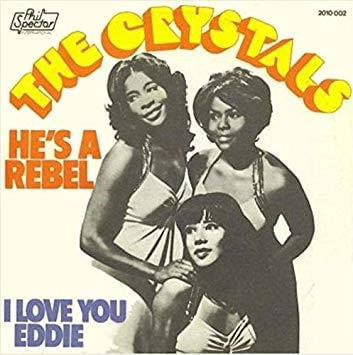

The Crystals/Gene Pitney, “He’s a Rebel.” Pitney had a lot of hits, but he didn’t write most of them. And he couldn’t have released his own version of “He’s a Rebel” in 1962, at least not without changing it to “She’s a Rebel,” which wouldn’t have had much of a chance in those pre-feminist times. But write it he did, and it was taken to #1 by the Crystals, though the lead vocal was actually done by a singer not in the Crystals, Darlene Love—something that’s fairly well known now, but was unknown then. Another peculiarity about this recording was that it had to fight off another version by Vikki Carr, which it did, pretty easily. Carr’s rendition is pretty stiff, and the Crystals’ (or Love’s, if you prefer) was far more soulful, as well as benefiting from one of Phil Spector’s definitive Wall-of-Sound productions.

This wasn’t the only hit Pitney wrote for someone else, as he also co-penned “Hello Mary Lou,” a big rockabilly-pop single—and one of the best and hardest-rocking—for Ricky Nelson. Yet “Hello Mary Lou” was a B-side to Nelson’s #1 “Travelin’ Man,” although it became almost as big a hit, reaching #9 on its own. Pitney put out his own version a little later as an album track, and while it’s okay, it’s not a match for Nelson’s, which benefits from a sparkling James Burton guitar solo.

Getting back to “He’s a Rebel,” while it could be naturally assumed that Spector’s production was the key to making the song a hit, his touch wasn’t infallible. There was another instance where a Spector-produced original version was the relatively stiff flop, and a much different arrangement a huge classic hit. Spector produced the original, forgotten version of “Twist and Shout” by the Top Notes. But it took the Isley Brothers’ vibrant cover to make it a hit (and of course the Beatles’ sensational version was an even bigger one).

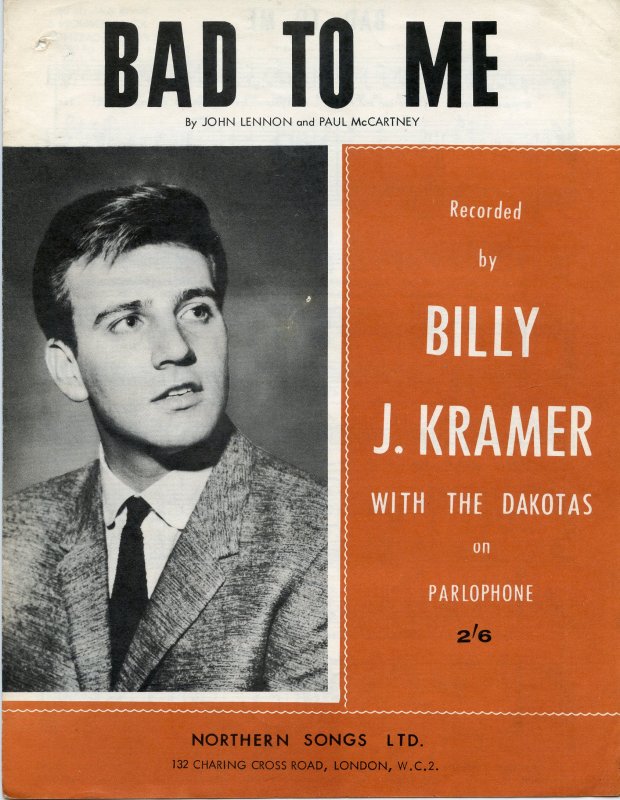

Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas/The Beatles, “Bad to Me.” Speaking of the Beatles, as previously mentioned, John Lennon and Paul McCartney wrote quite a few songs that the Beatles didn’t put on their own discs, but which found a home on other releases. When asked about such gifts in their early years, they’d diplomatically reply that they simply felt that a few of the songs they’d written weren’t suitable to do themselves and would be better handled by others. In truth, they were probably limiting the giveaways mostly to castoffs that weren’t as good as, and were more lightweight than, what the Beatles were reserving for themselves. That principle probably holds true for many giveaways by many songwriters throughout rock history.

Still, most of those semi-rejects are fun and catchy enough to hear, if hardly on the level of what the Beatles were putting on their own records. Kramer was one of the most frequent beneficiaries of Lennon-McCartney surplus, and “Bad to Me” was the best of their Merseybeat-styled extras. Unlike most of them, it was just about good enough to imagine as filler on one of their 1963 LPs. A very basic acoustic demo of the Beatles (probably Lennon solo, possibly with a little help from McCartney) doing their own version finally came out on iTunes a half dozen years ago (after being bootlegged for many years). Despite the rudimentary recording quality, it’s much better than Kramer’s anodyne interpretation.

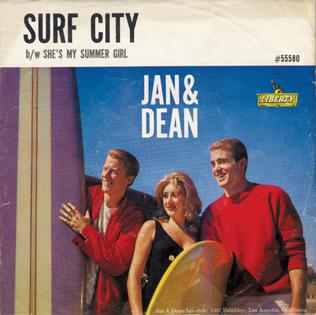

Jan & Dean/The Beach Boys, “Surf City.” I didn’t hear “Surf City” until around 1973, since I was only a year old when it first came out in 1963. I was well aware of the Beach Boys by 1973, however, and when I first heard “Surf City” on an oldies station, I was sure it was the Beach Boys. I’d be surprised if some of you reading this didn’t have the same reaction, whenever you first heard it. There was a good reason for this: Brian Wilson co-wrote the song with Jan Berry. “Surf City” was a huge hit, reaching #1 before the Beach Boys themselves had any #1 singles.

A few years ago, I asked Dean Torrence of Jan & Dean whether Wilson didn’t realize how big “Surf City” could be before letting Jan & Dean work on it. “He think he saw the potential,” Dean responded. “Brian probably very rarely worked on something that had no potential. But I sure think he, in comparing the two, just thought ‘Surfing USA’ had a lot more potential. And so did we. I mean, it was perfect. It was kind of a simpler song. It’s in E, and it’s Chuck Berry. We certainly loved Chuck Berry; obviously Brian did too as well. He couldn’t go wrong by liking Chuck Berry and being influenced by Chuck Berry. And ‘Surfing USA’ is just a straight old backbeat. ‘Surf City’ was kind of a shuffle, and was a little bit more complicated.

“I think creative people can kind of lose interest in a creative piece that they’re working on, and not be as motivated by that particular project, because you got something else in your mind that you’re also tinkering with. I’m sure he knew there’s potential, or he would have been embarrassed even to give it to us. So I’m sure he knew it was good.

“What we did to it, though, was we took it ten or fifteen levels above just the pure song in terms of cutting a track, and discovering the Wrecking Crew and all that. I think the tracks and the recording techniques that we used for [1963] were pretty unbelievable. The song was kind of a good song, and a Brian Wilson song, again, it’s always gonna be good. But the production that Jan put in relationship to the song really pushed it over the top.

“Even Brian, when he heard it, was blown away. Maybe at that point, he probably realized, this is really, really good. But it wasn’t as though he was gonna ask for it back or anything. As a songwriter, he was probably thrilled. That’s the way he looked at it—‘This is a song I didn’t finish, and I am a songwriter. I’ll get credit on it anyway. And I got a publishing company. So I’m doing exactly what I should be doing at my age, being a songwriter. And record producer.’”

I think this is the very best recording on this list, and certainly it’s one of the most successful. The Beach Boys probably missed out on a big hit, but they’d have plenty others over the next few years, and Jan & Dean did as good a job on the song as the Beach Boys probably would have. So to use a cliché that wasn’t in use in 1963, “It’s all good.”

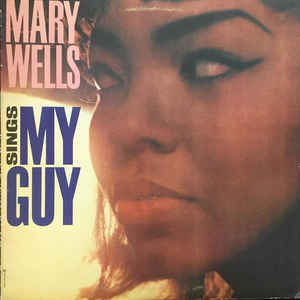

Mary Wells/Smokey Robinson, “My Guy.” Smokey Robinson wrote so many songs for other Motown artists that it’s really grounds for an entire article in itself, if not a book. Plenty of songs he wrote for others, rather than his own band the Miracles, were big hits, especially for Mary Wells and the Temptations. As a #1 single, “My Guy” is hardly an obscure pick, but I think it’s the best of the lot. It’s also not something he could have sung with the Miracles, at least without changing the title to “My Girl.” And that would have meant he couldn’t have co-written the #1 song he actually did title “My Girl” for the Temptations.

This entry also gives me cause to note that while historians often speculate about what might have happened had legends like Janis Joplin, Buddy Holly, and Otis Redding not died young, they don’t always often discuss other what-ifs that weren’t death-related. Robinson wrote (or co-wrote) and produced a number of hits for Wells, also including “Two Lovers,” “The One Who Really Loves You,” and “You Beat Me to the Punch.” It was a great artist-producer team, and when Wells left Motown after “My Guy,” she couldn’t work with Robinson anymore, or record his fresh compositions. She lived for another few decades, but none of her post-Motown records were big hits or, more importantly, nearly as good.

It’s an artistic tragedy that the partnership was cut off. In an alternate universe, what would have happened if she’d stayed at Motown and, most likely, kept working with Robinson? We don’t know, but I bet there would have been a series of hits to come, and that she’d be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame — which she deserves to enter anyway, based on the run the pair did have.

Peter & Gordon/The Beatles, “World Without Love.” I think this is clearly the best of the Beatles’ giveaways. Whatever anyone’s opinion, it was certainly the most successful, getting to #1 in the UK and US (where P&G were the first British Invasion act to top the charts after the Beatles). It’s now well known that Peter & Gordon got access to this, as well as several other Lennon-McCartney extras, since Paul was going out with Peter’s sister, Jane Asher, and living in the Asher household. Peter & Gordon’s Lennon-McCartney covers were really McCartney covers, as he was the dominant and indeed possibly sole writer of all of them. John Lennon didn’t like “World Without Love” because of the lyrics, especially the opening line “please lock me away.” But while it’s hard to figure where the Beatles might have placed it on their own releases, it’s certainly a good early British Invasion-style tune, with fine Peter & Gordon harmonies and a somewhat more forceful arrangement than most of the early Lennon-McCartney donations.

Of course Lennon and McCartney gave away quite a few other songs in the ‘60s. If you want to read about all of them in detail, I’ll take a second to plug my book The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film, which has a whole lengthy chapter dedicated to the subject. For the past few years, Peter Asher’s been presenting a combination music/storytelling show in New York, San Francisco, and London where he talks about getting “World Without Love,” and plays McCartney’s brief, primitive solo demo of the song. He also tells the story of how the duo got access to another composition by a different star…

Peter & Gordon/Del Shannon, “I Go to Pieces.” Del Shannon had already recorded a version of his composition “I Go to Pieces,” and produced an unreleased version by obscure soul singer Lloyd Brown, before Peter & Gordon became aware of it. As Asher tells it in his show, Shannon offered it to the Searchers during an Australian tour, but they turned it down. Peter & Gordon were also on that tour, and let Shannon know they’d like to do it. It became their first hit (at least in the US) not bearing a Lennon-McCartney composer credit. Shannon’s own version came out on one of his albums a little later, and while it’s not too different from P&G’s’, I prefer it, since it’s not as heavily orchestrated, though it’s missing the dual vocal harmonies of the Peter & Gordon arrangement. The Lloyd Brown version, by the way, has since circulated, and has a gentler slightly jazzy soul-pop feel, though it’s not as good as either Shannon’s or Peter & Gordon’s.

The Toggery Five/The Rolling Stones, “I’d Much Rather Be with the Boys.” The Rolling Stones, or more properly Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, wrote quite a few songs given to other artists, even if these haven’t gotten nearly as much attention as the Lennon-McCartney giveaways. In part that’s because not many of these Jagger-Richards compositions were hits, “As Tears Go By” (Marianne Faithfull’s debut single) being a notable exception; Gene Pitney also had a British hit with their “That Girl Belongs to Yesterday” in early 1964, before the Stones had even entered the US charts under their own name. But also it’s in part because most of the songs weren’t that good, and were not only more lightweight than what the Stones recorded themselves. Most of these surplus items date from the mid-‘60s, when Jagger and Richards were first starting to write. They usually weren’t much like what the Stones were doing on their own, with an ersatz Merseybeat feel. Numerous demos of these (most or all apparently only with Jagger and Richards’ participation) are on the Rolling Stones’ outtake compilation Metamorphosis, which didn’t come out until 1975.

One of those Metamorphosis tracks, “I’d Much Rather Be with the Boys”—actually bearing the unusual songwriting credit of Keith Richards and manager/producer Andrew Oldham, sans Jagger—was done back in 1965 by a British group that never had a hit, the Toggery Five. To my mind it’s the best of the Stones’ giveaway covers, and actually considerably better than the Metamorphosis demo. It might not be the greatest of songs, but it’s fairly catchy in a sort of Merseybeat-meets-the-Drifters way, the tempo and tune owing a lot to Drifters hits like “Under the Boardwalk” (which the Stones, of course, covered in 1964). Also, however, the Toggery Five attack the song with real rock zest, in contrast to the Metamorphosis version, which like many early songs on that LP has wimpy orchestrated pop production. The harmonies are real good too, and the cut’s executed with the kind of polish that makes you think the group were certain they had a hit in the can. They didn’t, and the Toggery Five were forgotten (and only got to do a couple singles total), though fortunately their version has been reissued a few times.

By the way, the Rolling Stones themselves didn’t forget about the song after they were done with it. In the expanded DVD version of the 1965 Charlie Is My Darling documentary, there are scenes of Mick and Keith busking through the song acoustically in what looks like a hotel room, during the end credits. It’s hard to tell whether they’re doing it because they like it or they’re making fun of it, but it’s an interesting and unexpected bonus.

Trevor Gordon/The Bee Gees, “Little Miss Rhythm & Blues.” The Bee Gees, and especially Barry Gibb, wrote lots of songs in their early days they didn’t manage to jam onto their own prolific releases. Even before they moved from Australia to England in 1967, they’d already placed a lot of songs with other artists, primarily in Australia. Most of them aren’t so memorable, but Trevor Gordon’s Barry-written “Little Miss Rhythm & Blues” stands out both for its relative quality and an almost earthy rock and roll style that’s not associated with the Bee Gees. Sort of like Jerry Lee Lewis meets Merseybeat, it’s quite cool, if a bit underproduced, with the Bee Gees themselves contributing enthusiastic background vocals. Gordon would also go to England and have a British hit as part of the Marbles with the Brothers Gibb-penned “Only One Woman,” though it didn’t catch on in the States.

While not exactly the kind of thing to win them points for retroactive hipness, Barry Gibb also managed to place a song with an American star a couple years before leaving Australia. In November 1964, Wayne Newton recorded his melodramatic, somewhat Gene Pitney-esque ballad “They’ll Never Know,” which was on Newton’s Top Twenty LP Red Roses for a Blue Lady the following year. This was the first song written by any of the Bee Gees to be released outside of Australia and New Zealand.

The Thoughts/The Kinks, “All Night Stand.” There were quite a few Ray Davies songs (and even one Dave Davies song) that weren’t released by the Kinks, but issued by others. I know this might be starting to sound like a broken record, but it’s unsurprising the Kinks didn’t cut most of them on their own, because they weren’t as good or gutsy as the Davies songs they did lay down. Nor were they that successful, with the exception of the placid ballad “This Strange Effect,” a huge hit for Dave Berry in Holland, though it only made #37 in his native UK. (The Kinks did record a version of “This Strange Effect” for the BBC that eventually found release, but did not put it on their studio discs.) The eerie “I Go to Sleep” is pretty good, but I much prefer the Kinks’ sparse demo (eventually released as well after getting bootlegged) to the one by the artist who was able to record it back in the mid-‘60s, Peggy Lee.

An exception in both quality and energy is “All Night Stand,” a fairly penetrating look at the troubling undercurrents of Swinging London. It’s got the same kind of peppy brashness as numerous 1966 Kinks songs like “Dedicated Follower of Fashion”—not as raunchy as their first big singles with a modified power-chord arrangement, but not as subdued as what they’d get into by 1967 and 1968. While the Thoughts don’t put much personality into it, it probably doesn’t sound much different than how the Kinks would have done the tune. Of course it would have had much more personality with a Ray Davies vocal, as you can hear on a demo that found release after doing the rounds on bootleg.

“All Night Stand” seems like a reasonable contender for release on their 1966 LP Face to Face. Why didn’t it make it? Maybe it was considered too downbeat or serious for a collection that, for all the satirical sophistication of most of its songs, usually had a fairly cheery wit. Thematically it might have fit in better than the one song, the closing cut “I’ll Remember,” that seemed like a throwback to the earlier Kinks in its standard romantic lyrics. Which brings me to a question I’ve never read posed: was the use and placement of “I’ll Remember” on Face to Face deliberate, almost like it was a tongue-in-cheek farewell (thus the phrase “I’ll remember”) to the more standard, simpler romantic pop lyrics Davies used on the Kinks’ earlier records?

The Sons of Adam/The Other Half/Love, “Feathered Fish.” Here for a change we have a way-obscure song done by two groups that never came close to a hit, written by the leader of a band that, though very famous, never quite got beyond cult status. “Feathered Fish” was written by Love’s Arthur Lee, and has the kind of manic energy and weird free-associating lyrics of some of Love’s hard-rocking early songs, like “Stephanie Knows Who.” Why Love themselves didn’t issue a version isn’t clear. It would have fit in fairly well on the first side of their second LP, Da Capo, but maybe it wasn’t considered quite as strong as the six excellent songs that did make it on side one. Had Love decided to make a whole LP of real songs instead of devoting side two to the long jam “Revelation,” it certainly should have made it. But that might have meant padding the album with slightly lesser songs. That would have worked better than putting an interminable blues jam in their place, but what’s done is done.

Lee liked a fellow Los Angeles band, the Sons of Adam, who featured terrific guitarist Randy Holden and drummer Michael Stuart, whom Lee would poach for Love in autumn 1966. Before that, Lee offered the group “Feathered Fish.” According to Sons of Adam rhythm guitarist Jac Ttanna, Arthur actually offered them three songs, one of which, “Seven and Seven Is,” would become Love’s only Top Forty hit. Oddly, neither Stuart nor Holden would be in the band by the time Sons of Adam finally got around to recording “Feathered Fish” on their third and final single in 1967, shortly before they split. It’s a good garage-psych performance, with constant stop-start tempos and the kind of breezy raw early psychedelia that peaked in L.A. for just a magic year or so from around mid-1966 to mid-1967.

Holden did record “Feathered Fish,” however, as part of his next band, the Other Half, one of the most underrated psychedelic late-‘60s outfits. Included on their sole LP (whose label mistakenly credited the composition to Country Joe, sans McDonald), it’s a starker yet more powerful version, with almost shouted menacing vocals and thrilling yelping, sustain-heavy Holden guitar. Randy nonetheless told Ugly Things that “Other Half didn’t do it as well as Sons of Adam,” and noted in the same interview that he’d cut a much better version with them while he was still in the band.

Manfred Mann/Bob Dylan, “The Mighty Quinn.” This is hardly an obscure song, or hit cover. And there were a lot of Dylan compositions in the ‘60s that he didn’t put on his records, but were recorded by someone else. In fact, Manfred Mann had already had a #2 UK hit with one of them, “If You Gotta Go, Go Now,” in 1965.

Some Dylan fanatics have a hard time accepting the possibility that other artists might have performed any of his compositions better than Dylan himself did. But I’m siding with the masses on this one. Manfred Mann’s “The Mighty Quinn,” which made #1 in the UK and the Top Ten in the US, is much better than the original, which Dylan cut with the Band as part of a massive collection of “Basement Tapes” in 1967. That original—the second of the two takes was finally released in 1985, and both takes are now on The Basement Tapes Complete—is skeletal. Manfred Mann made it much more tuneful and fun, emphasizing a catchy-as-hell chorus, great soaring harmonies at the end of the verses, and Klaus Voormann’s unforgettable interjections of pennywhistle. When I play the versions back to back in rock courses I teach, students virtually unanimously prefer the Mann cover.

Should this be considered a giveaway? Sort of, because although Dylan didn’t write it with Manfred Mann in mind, it was on a fourteen-song publishing demo of Basement Tapes recordings meant to solicit cover versions. Take one by Dylan and the Band did soon appear on the first popular Dylan bootleg, Great White Wonder, but not until 1969, more than a year after Manfred Mann’s hit.

If Manfred Mann’s polishing of Dylan songs is considered sacrilegious, it’s worth considering Mann’s comments to me from an interview nearly twenty years ago. He saw the strengths of his group’s Dylan covers as “the ability to change it, because it always seemed as if the original version was very personal to him. It didn’t seem like a definitive version, in some funny way. I don’t mean that in any way as an insult, ’cause I absolutely loved the original versions. But it just seemed that there was space there to do something, and make it different. Which you couldn’t do with Elton John—he seems to have done it in the standard way. Dylan did it in a very idiosyncratic way. And therefore, there was the space to do it in a different way. I almost feel that I straightened them out in a way.

“We approached it without any respect for the original. That’s absolutely essential. You can’t go around with so much respect for the original that you can’t function. It was quite simply, ‘What can we do with this?’ And my general thing was to have it in music form, in front of me in paper, and just play it and play it and play it until in the end I wouldn’t refer to the original record, after I knew it. If you play it long enough, you find you’re playing it your way.” His way would extend to taking liberties that some Dylanologists would see as heresy, though they ruffled Mann not at all: “I would cut sections out if I needed to. In ‘Just Like a Woman,’ I cut out the whole middle bridge. We didn’t want to do it, and we just didn’t do it.

“We had the songs that everybody else had missed, where the original versions were sometimes quite idiosyncratic and a bit left-field. But I could use it. I was simply a bit of a predator, looking for material.”

Jefferson Airplane/The Byrds, “Triad.” “Triad” is pretty infamous in the Byrds’ history, as one of the straws that broke the camel’s back in leading to David Crosby’s departure (or, more precisely, firing). This song about a ménage a trois was recorded during the sessions for their fifth album, The Notorious Byrd Brothers, but not used. Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman, who’d jointly fire Crosby in late 1967, didn’t like the song, to the frustration of the composer, who felt what he was writing was good enough to get released. And certainly better than Carole King and Gerry Goffin’s “Goin’ Back,” which did make the album, although Crosby had no enthusiasm for its inclusion.

In Johnny Rogan’s Byrds: Requiem for the Timeless: Vol. 1, both clarified that “Triad” wasn’t the leading factor in their decision. “We didn’t like the song at the time,” Hillman told Rogan, adding, “I don’t think it was a moral decision. The song just didn’t work that well. David was drifting and bored and wanted to do something else, and that song just added fuel to the fire.” McGuinn agreed: “‘Triad’ wasn’t the crux of it, that was nothing really. It was just a song that I didn’t think was in particularly good taste.”

Crosby found a home for the song, however, with his friends Jefferson Airplane, who included it on their 1968 album Crown of Creation. “What is he saying that is bad?,” said Grace Slick in Jeff Tamarkin’s Got a Revolution! The Turbulent Flight of Jefferson Airplane. “If the two women want to live there, and he wants to live there, who cares? His band wouldn’t let him and, yeah, I’ll sing it! I wouldn’t do that [a threesome] personally, but I don’t have a moral issue with it.”

The controversy has added luster to a song that actually isn’t that great. The Byrds’ languid version, now available as a bonus track on The Notorious Byrd Brothers, wouldn’t have stood out as a good addition to the album; in fact, it wouldn’t have fit that well. And it’s not as good as “Goin’ Back,” which is the kind of sparkling folk-rock at which the Byrds excelled. I like Jefferson Airplane’s version of “Triad” better, and though it wasn’t among their best tracks, it fit in better on Crown of Creation.

Fairport Convention/Joni Mitchell, “Eastern Rain.” In their early days, prior to their heavy emphasis on rocked-up British folk, Fairport Convention excelled at well-chosen covers of American folk-rock songs. Some of them hadn’t been released by the composers when they recorded them for their first two albums, or their late-‘60s BBC sessions. One such highlight was Joni Mitchell’s “Eastern Rain,” from their first album with Sandy Denny as woman vocalist, What We Did on Our Holidays (titled simply Fairport Convention in the US). It’s given a beautiful delicate folk-rock arrangement, from the rain-mimicking guitar plucks to the rich vocal harmonies and Denny’s own characteristically glowing lead singing.

Mitchell did perform a solo folk version live in the late-‘60s, as you can hear on bootleg, but did not put it on her official discs. Fairport did a couple then-unreleased-by-Mitchell songs on their 1968 debut album, but Joni did put both of those on her second album, Clouds, in 1969. As Fairport’s Iain Matthews confirmed when I interviewed him for my book Eight Miles High: Folk-Rock’s Flight from Haight-Ashbury to Woodstock, producer Joe Boyd “had a direct line to her publishing demos and supplied us with whatever we could handle.”

Fairport, by the way, were another act that put out then-unreleased Dylan songs in the ‘60s, like The Basement Tapes’ “Million Dollar Bash,” which is on their third album, Unhalfbricking. That LP also includes a considerably older Dylan song that the composer had not issued on his records, “Percy’s Song.” Although it’s not too well known, I’d go as far as to say Fairport’s BBC version is one of the best Dylan covers, and only outclassed by Manfred Mann’s “The Mighty Quinn” as the finest of a composition not yet released in Dylan’s official catalog, though his 1963 outtake made it onto 1985’s Biograph box.

Marianne Faithfull/The Rolling Stones, “Sister Morphine.” Although “Sister Morphine” is one of the better known songs from the Rolling Stones’ 1971 album Sticky Fingers, it’s still not too widely recognized by the general public that the first version came out on a rare Marianne Faithfull single in 1969. Its status as a “giveaway” is a little diluted by the composer credits, which Faithfull herself shared with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. Sticky Fingers only credited Jagger and Richards, but as Faithfull explained in the liner notes to the 2018 compilation Come and Stay with Me: The UK 45s 1964-1969:

“Mick is mean. He’ll always be a student of the London School of Economics! Keith Richards wrote to [Stones publisher] Allen Klein and told him that I’d written the lyrics. Jagger and I had split up, very bad blood and all that. Keith Richards told him that I did write the words and I needed the money. So now and again, I get a royalty check for ‘Sister Morphine.’ I’ve been living off ‘Sister Morphine’ for years. I just got one today. £485!”

The Rolling Stones’ version of this downer drug song is pretty good, but I’d give Faithfull’s the edge, if only a slight one. This is the point where her voice started to lower and become more earthy, in contrast to the angelic, virginal tone of her mid-‘60s hits. She really sounds like she’s living the lyric, not just singing it, though the worst of her drug problems were yet to come. As she herself states in the aforementioned liner notes, “I was the character in the song.”

Why aren’t more people aware of Faithfull’s version of “Sister Morphine,” although it’s been reissued a few times? Because of its controversial subject matter, the single was withdrawn by Decca Records in the UK, where only 500 copies are reported to have been issued. But I haven’t read that it was censored in the US or other countries, and in any case, it was the B-side to the relatively innocuous Gerry Goffin-Carole King composition “Something Better.” Despite its quality, “Sister Morphine” was simply unlikely to get airplay anywhere in 1969.While that finishes my list of selected favorites in this niche category, there were quite a few other oddball entries that are worth discussing, even if they were of uneven or even unimpressive quality. I’ll write about some of those in my next post.

Love the Jan & Dean and Manfred Mann quotes. Also like your alt history speculations about Mary Wells. As always, my deep source on everything ’60s music.