We all know that much less music was performed in 2020 than in any other year in our lifetimes. How did that affect the reissue business? As with music history books and films, not as much as you might expect. In part that’s because it’s easier to reissue old music than it is to record new music this year, even though there are still logistical difficulties in researching, retrieving, and repackaging tapes.

Even with many record retailers closing or drastically cutting their hours and access, record sales haven’t suffered as much as many other businesses have. Those music consumers still lucky enough to have assets and employment have more disposable income than usual, now that traveling and going out to eat and see entertainment are barely or not possible. And with people at home much more than usual, there’s more time to fill with listening.

So there was still about as much reissue output, and variety of same, as there was in most years. The word “reissue” might not be the best term for some of the items on my list (including the one at #1), as some of them partially or wholly feature music that’s being issued for the first time. If we’re talking music from decades past that was presented on worthwhile albums released in 2020, however, that’s what qualifies for this list, whether it’s been around before or not.

I appreciate the visits of many readers to the posts of my best-of lists over the past few years, as well as the interesting and insightful comments they sometimes generate here and elsewhere. I do get occasional comments from readers who seem to expect something different from what I offer. To clarify:

This is a list of my personal favorites of the albums featuring historical rock recordings released in 2020 that I was able to hear. It’s not a list or compendium of what other writers, listeners, publications, and music communities have deemed their favorites, or considered the most important and historically significant. While packaging is a factor in my selections, it’s not the only or main one. Just because a box has all the notable rarities, great liner notes, or a new mix or remastering doesn’t mean I’ll pick it. I won’t select it if I don’t like the music or the artist, no matter how many bells and whistles it has.

Music can be taken as seriously as religion and politics, and omissions from my lists have even generated some anger in the past. If there’s anger about anything, I ask that it gets channeled toward helping to rebuild my native US, and the world as a whole, after the disastrous four years of the outgoing administration. Here’s hoping, to quote the Who, that “21 is gonna be a good year” after the new administration is inaugurated.

In keeping with those hopes, it’s appropriate that my #1 pick hails from a country that has taken a more humane and sensible approach to our current crises than the US has. Here’s to both neighboring nations following a similar path over the next decade.

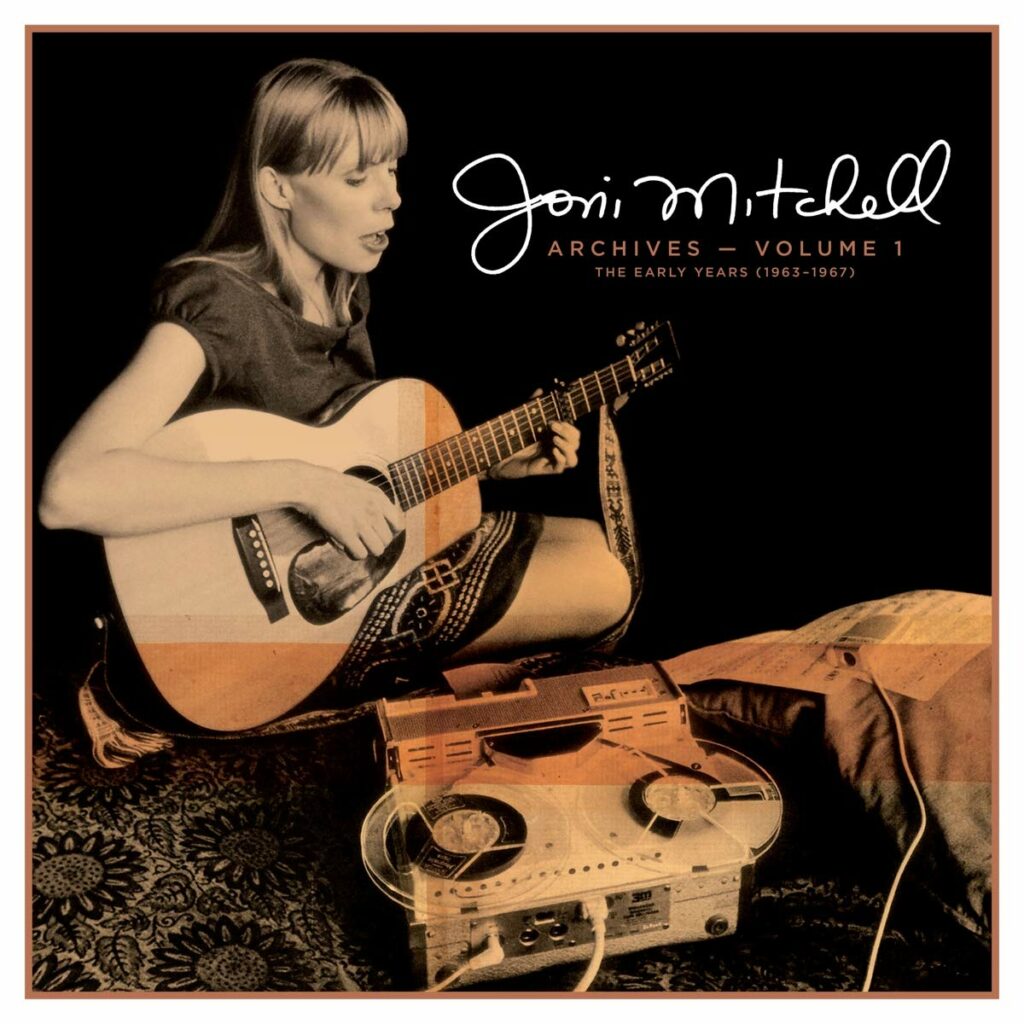

1. Joni Mitchell, Archives Vol. 1: The Early Years (1963-1967) (Rhino). Before her first album came out in 1968, Joni Mitchell was already a prolific songwriter who’d been performing on the North American folk circuit for about five years. Some of her unreleased material from this era has circulated on bootleg, and this five-CD box contains not only some of that, but much more. Documenting her growth from a traditional folk singer to a superb songwriter, it fills in a big gap in the discography of a major performer. Taken from live performances, radio shows, TV programs, demos, and home tapes, none of the nearly hundred tracks (not counting the couple dozen or so spoken introductions) have been officially released. Many of them haven’t even unofficially circulated.

As the songs on disc one that span 1963 to early 1965 reveal, Mitchell began as an interpreter of traditional songs with a voice and style not unlike early Judy Collins. Even at this point, she was better than most of the numerous women folk singers from the final years of the folk revival, even when she accompanied herself on four-string ukulele on the earliest recordings.

By 1965, she’d already moved toward highly original songwriting with her first outstanding composition, “Urge for Going” (soon to be covered by Tom Rush, and then for a country hit by George Hamilton IV). There were still echoes of trad folk in the cover of John Phillips’s “Me and My Uncle” (quite a good version, actually) and her own ramblin’ road ode “Born to Take the Highway.” But her singing—which on the earliest tapes deploys a high, pristine tone a la Collins, Joan Baez, and their many imitators—quickly developed a wider, swooping range. The ukulele was retired, and her underrated, masterful acoustic guitar work started to bloom, with growing use of unusual tunings and rhythms as the ‘60s progressed.

In late 1966 and 1967, classics like “The Circle Game,” “Night in the City,” “Both Sides Now,” and “Chelsea Morning” entered her repertoire. It’s mysterious that she wasn’t signed to a recording deal earlier, as she was clearly getting on par with the best singer-songwriters of the time, though maybe her failure to branch into electric folk-rock held her back. Early interpreters of her work (also including Buffy Sainte-Marie, Ian & Sylvia, and Dave Van Ronk) covered some of the songs here before Mitchell had a record out, but Joni’s versions here are confident and more definitive.

Although 118 tracks are listed for this set, keep in mind not only that more than a couple dozen are spoken intros, but also that there are a good number of multiple versions. However, there aren’t more than three of any one tune (“Both Sides Now,” “Urge for Going,” and “Night in the City” are all heard three times, for example), and the versions are spaced out widely enough from each other that the redundancy’s not an annoyance. Sometimes you can hear a definite difference or progression between renditions, as you can in just four months between the two of “Eastern Rain.”

The sound quality varies between excellent and okay, and while some hiss can be heard on the tracks with lowest fidelity, none of them are so muffled as to be unenjoyable. And while the sheer number of spoken introductions might sound daunting, they’re actually fairly interesting, and show her a warm and personable (if sometimes a bit flighty) performer even as she struggled to gain a recording contract. Best is one where she bluntly, if accurately, tags David Blue as a Dylan imitator, noting that Blue emulated Dylan’s grouchy side and Eric Andersen Dylan’s humorous side, almost like it was a tennis match between the two.

Best of all, this box has many original Mitchell compositions she never placed on her studio records. There’s a reservation attached to that bonus, however. Almost all of them are interesting and pleasing to hear, but she wisely selected her best work for inclusion in her early records. There are earlier versions about a dozen songs that would crop up on her first four LPs, including six that would show up on her debut album.

Few of the others here stand out as on the level as those that made the cut, and some are preciously lightweight. Exceptions are “Eastern Rain,” which Fairport Convention covered magnificently on their second album, and “Urge for Going,” which only made it onto a non-LP B-side. “Day After Day,” referred to in the liners as her first composition, is pretty strong too.

Interesting oddities include a May 1967 cover of Neil Young’s “Sugar Mountain,” well in advance of the release of Young’s version; a wordless improvisation that isn’t a mere throwaway, displaying her facility at devising jazz-folk melodies; and two versions of “Dr. Junk,” which as she notes uses a Bo Diddley rhythm at times (this was also done as a very obscure cover by the Ian Campbell Group). “Songs to Aging Children Come” has a plain folk arrangement that’s much different from the one on her second LP, which used extensive multi-track vocals.

There are more pre-1968 recordings in unofficial circulation than what made it onto this box. But this is a well assembled retrospective that presents much or all of the cream without overloading multiple versions. Considering Mitchell’s recent serious illness, an unexpected extra is her recent interview about this era that fills up most of the box’s booklet. (This review will also appear in a future issue of Ugly Things.)

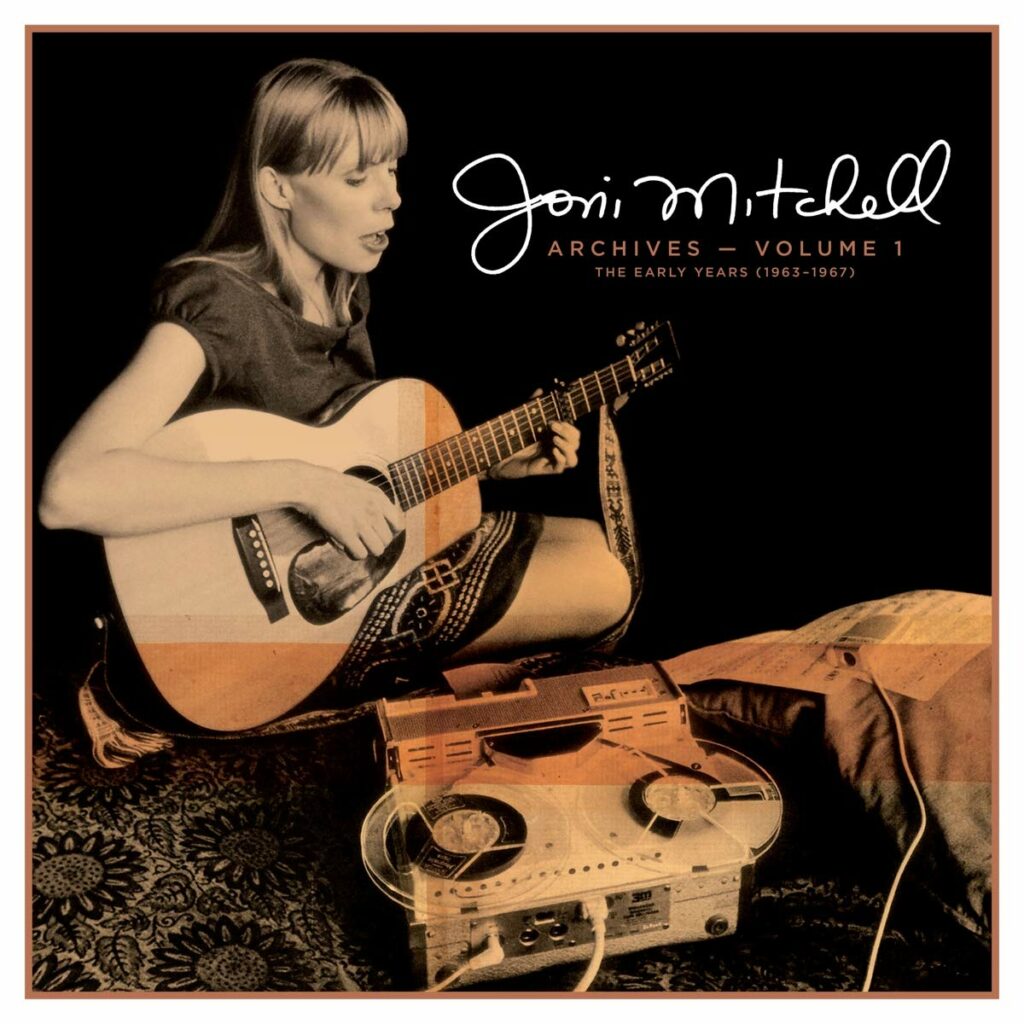

2. Donovan, Live 1965-1969 (London Calling). The title of this double CD could have been more precise; these thirty tracks weren’t from conventional concerts, but from BBC radio sessions. As most of his ‘60s UK peers are represented by a BBC collection or two (or more), it’s a little surprising it took so long for a Donovan BBC compilation to appear, especially as almost all of the tracks have good, clear sound. (And those with the worst fidelity aren’t much worse than the best.) If this was fully authorized, it seems like it would be on a major label, not on a relatively unknown one. But it’s available for sale in major outlets, and so should be considered a “real” release, if a somewhat gray-area one.

In common with most BBC collections, it’s a mixture of good performances that stick closely to the studio arrangements with some interesting variations and choice rarities. Of most interest will be four 1965 performances from his folk phase of songs that never appeared on official Donovan discs. “Who Killed Davy Moore,” one of two Bob Dylan compositions here that Dylan himself didn’t release in the ‘60s, is more melodically interesting than Dylan’s arrangement, with a minor-keyed tune that probably follows the version Pete Seeger put on the 1963 album Broadside Ballads Vol. 2. “Daddy You’ve Been on My Mind,” while a little less striking, is Donovan’s take on Dylan’s “Mama You’ve Been on My Mind,” the title changed as he modeled it on Joan Baez’s 1965 cover where “Mama” was changed to “Daddy.” It’s still a strong performance.

There’s also a decent cover of a song by a less celebrated hero of Donovan’s, Bert Jansch, with “Running from Home.” He also does “Working on the Railroad” – not the overly familiar kiddie singalong, but a fairly gutsy folk-blues he likely learned from a recording by American folkie Jesse Fuller.

Some, if not a huge number, of cuts deviate in notable ways from the studio counterparts. “Young Girl Blues” is a real highlight, as the Mellow Yellow LP version is solo acoustic, but this radio reworking has a full jazzy band and some different lyrics. It’s one of the rare BBC performances from rock artists of the time that could be fairly preferred to the studio counterpart, and is a very observational piece where the radio version heightens the moodiness to good effect. “Barabajagal,” actually recorded at Donovan’s cottage, goes the other way by offering a solo acoustic rendition – not as memorable as the rocking hit single, but memorably different and good on its own terms. “Bert’s Blues,” unlike the full-band jazzy baroque setting on Sunshine Superman, is just Donovan on acoustic guitar and Spike Heatley on upright bass; I prefer the studio version by some distance, but this is worth hearing too. “Lalena,” in two versions (one with strings and one without), has some different lyrics in the third verse of the string-backed take.

Even on the songs that aren’t too different from what you’re used to hearing on Donovan’s ‘60s records, the performances are confident and he’s in very good voice, as well as playing acoustic guitar very well. That’s particularly evident on the numerous 1965 tracks (fourteen in all), where he delivers fine and sparsely (if at all) adorned renditions of his pre-rock hits and obscure covers found on his early releases, like “Little Tin Soldier” (written by Shawn Phillips) and “Candy Man.” And there are brief interviews where Donovan offers some thoughts on folk music and his work, though they don’t last long enough to get too deep.

There are things to criticize about this batch of radio sessions. Some of them from post-‘65 sound like at least some of the components might have been lifted from the studio versions. “Jennifer Juniper” and “Hurdy Gurdy Man,” to name a couple, sound extremely similar to the hit singles, and “There Is a Mountain” is mainly differentiated by an additional organ part. There’s a pretty big artistic distance between his best late-‘60s work (like the aforementioned hits) and his more lightweight ditties, a few of which are here, such as “The Tinker and the Crab” (in two versions) and “The Entertaining of a Shy Little Girl.” There’s nothing from 1966 (possibly he didn’t do any sessions that year, when he was caught in a complicated contractual dispute that held up his UK releases), and hence just one song from his best album, Sunshine Superman.

But overall, this reinforces Donovan’s stature as a major performer of the era. Not that he needed this compilation to do that; his reputation has risen steadily over the last few decades, since a low point when he was sometimes unfairly dismissed by historians and critics as a flower-power namby-pamby and/or Dylan imitator. It might not substantially redefine his legacy (few BBC anthologies do), but it’s absolutely a worthwhile supplement to his main body of work, and heartily recommended to fans of his earliest and best years. An excellent track-by-track guide to this collection by blogger Stuart Penney, incidentally, can be read at https://andnowitsallthis.blogspot.com/2020/03/donovan-live-1965-1969.html.

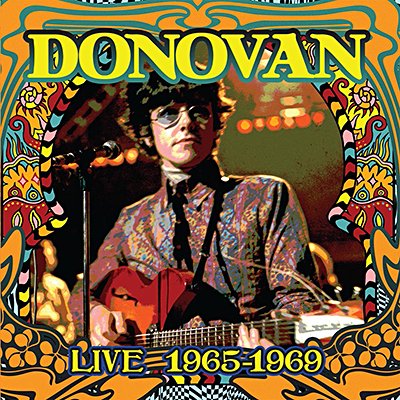

3. The Yardbirds, Live at the BBC Revisited (Repertoire). I’ve lost track of how often Yardbirds BBC sessions have been issued and reissued, even without counting the gray-area and bootleg releases on which some sessions have surfaced. And I’m not entirely sure whether this three-CD compilation marks the first time some of these have circulated, though any that haven’t been previously heard are alternate versions rather than songs that haven’t been available in any BBC performance whatsoever. Still, this certainly marks the most comprehensive package of Yardbirds BBC performances in one place. It also certainly has the best annotation of any Yardbirds BBC collection, Mike Stax’s thorough liner notes including first-hand quotes from drummer Jim McCarty and bassist Paul Samwell-Smith.

Note that just three tracks date from the Eric Clapton era, and these are from a live concert at the 1964 National Jazz & Blues Festival at which Mick O’Neill filled in for ill singer Keith Relf. Over two-thirds of this dates from sessions with Jeff Beck in 1965 and 1966 – not a drawback, since that was when the group were at their peak. A good part of disc three has 1967-68 sessions with Jimmy Page, however, and is well worth hearing, especially for the version of “Dazed and Confused.”

A number of songs they didn’t put on their studio releases are here, including “Spoonful,” “Bottle Up and Go,” the folk song “Hush-A-Bye,” Freddie King’s “The Stumble,” “Dust My Blues,” “The Sun Is Shining,” Curtis Mayfield’s “I’ve Been Trying,” Bob Dylan’s “Most Likely You’ll Go Your Way,” and even a group original (“Love Me Like I Love You”), though that last item an average soul-pop tune. While non-fanatics might not care too much about variations like a greater rhythm guitar presence on “Over Under Sideways Down” or different guitar lines on “The Train Kept A-Rollin’” and “Heart Full of Soul,” they’re the kind of things Yardbirds devotees treasure. The same goes for multiple versions of “Too Much Monkey Business,” “Evil Hearted You,” and “Love Me Like I Love You” that were recorded at the same session; they’re nearly identical, but then they’re among the tracks that have rarely or never circulated to my knowledge.

It should also be noted that if you’re enough of a Yardbirds collector to want a set like this, you’ll probably have a lot of it elsewhere. And, while this is another observation that makes some labels livid, the sound quality, while generally very good, is variable, and the minor sonic deficiencies on some cuts can’t be totally remedied by any amount of expert remastering. This is still a major supplement to their studio work, but the previous availability of much of it means I can’t quite rank it as high as the Donovan BBC anthology, none of which had previously been on the market.

Also released by Repertoire at the same time, by the way, was Blues Wailing: Five Live Yardbirds 1964. Not to be confused with their official debut album Five Live Yardbirds (recorded March 1964), this briefer set was recorded on August 7, 1964 at the Marquee (not July 25, 1964 at King George’s Hall in Esher, Surrey, as previously reported). It’s the same material, however, that was first issued back in 2003 as Live! Blueswailing July ’64, with new liner notes by Mike Stax.

4. The Honeycombs, The Complete ‘60s Albums & Singles (RPM). They might be thought of as a one-hit British Invasion wonder for 1964’s “Have I the Right,” but the Honeycombs actually cut quite a bit of material in their brief 1964-66 career as a recording act. They weren’t a one-hit wonder either, exactly, since “That’s the Way” was a Top Twenty UK hit and “I Can’t Stop” almost made the US Top Forty. Most of what they did remains unknown beyond the hard-bitten British Invasion collector world, though. And while they’re often thought of, with some justification, as kind of wimpy, a good number of their tracks were pretty good, if more due to Joe Meek’s imaginative and at times weird production than the modest talents of the group. This three-CD set—yes, there’s enough to fill up three discs to the gills, totaling 78 songs—has all three of their albums, plenty of non-LP singles, a few unreleased studio outtakes and radio performances, and even some mighty obscure solo 45s by group members Denny D’Ell and Martin Murray.

Really only about half of this is prime stuff, but it’s better than you might think. Meek’s production found a suitable outlet with this band, featuring squealing guitars, sped-up sounding D’Ell vocals, crunching drums, odd glissandos, and a general idiosyncratic squash, sometimes making the backup vocals sound truly fishbowl-generated. Some of their LP-only tracks and flop 45s/B-sides were supremely spooky, like “Without You It Is Night,” the admittedly pretty similar “This Too Shall Pass Away,” and “Eyes.” The original 45 version of “I Can’t Stop” was their greatest moment, enhanced by frenetic D’Ell yells, infectious stop-start tempos, and a general sense of nearly out-of-control euphoria. (The LP version, also here, is a ghastly, far inferior remake). “Something I Got to Tell You,” a rare vocal from drummer Honey Lantree, sounds like it could have been a hit, though the lyric “something’s giving me hell” might have blown any chance of that. Non-LP singles and B-sides like “That Loving Feeling,” “Should a Man Cry?,” “Please Don’t Pretend Again,” and “Can’t Get Through to You” are genuinely worth seeking out. And while “Emptiness” isn’t a great song, it has the distinction of being a Ray Davies composition the Kinks never recorded.

What are the drawbacks? Well, D’Ell’s voice, kind of like a wobbly Gene Pitney, will drive some listeners up the wall. The songs, mainly supplied by managers Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley, could be puerile, and not saved even by the best efforts of Meek (who wrote some of their other tunes). The live album In Tokyo might be rare, but it isn’t very good, and dominated by covers of American hits. Those obscure solo singles aren’t memorable; the radio performances and outtakes only somewhat interesting; and the historical liner notes disappointingly shallow, with much remaining unknown about how the songs were conceived and recorded. And if you want to subtract points, the Honeycombs didn’t write any of their own material (though Murray wrote his solo 45), making one wonder if they would have made any impact whatsoever without their producer and managers. More than fifty years later, however, does that matter so much? Their name was on a good number of enjoyable, unusual records, all of which can be heard here, even if the ride’s wildly erratic. For a more in-depth appraisal of the Honeycombs and this box, read my post from earlier this year.

5. Keith Relf, All the Falling Angels (Repertoire). Keith Relf made hardly any records on which he was the solo artist – just two obscure singles in 1966, in fact. Of course, he’s pretty famous as the lead singer of the Yardbirds, and to a lesser degree as part of the first lineup of Renaissance. He might be most (and most justly) noted for his contributions to the fierce British Invasion rock of the Yardbirds, but he also had a folky, introspective, and at times fragile vulnerable side that wasn’t always evident in the records he was involved with that came out in his lifetime. That imbalance is partially redressed by this 24-track compilation of obscurities and demos, spanning the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. Almost half of them are previously unreleased, and most of them didn’t come out before his death in 1976.

When working on his own or as part of the short-lived late-‘60s group Together (with ex-Yardbirds drummer Jim McCarty), Relf usually eschewed blues-rock and psychedelia (at which he was quite good) for more tender outings with an almost nakedly personal aura. There’s a nearly translucent quality to the cuts here that didn’t make it onto discs, as if Relf was not quite of this earth or at home here, with a mystical yearning too ethereal to withstand the everyday pressures of human existence. A few of the earlier tracks will be of special interest to Yardbirds fans, presenting brief demos of two of the better songs from their sole LP with Jimmy Page, “Glimpses” (at this point little more than a haunting chant) and “Only the Black Rose” (which, oddly, has a much more upbeat melody than the studio track). More polished, melodic acoustic folk-rock songs were done by Together; both sides of their rare 1968 single are here, along with a couple outtakes that came out on the 1992 double-CD expanded edition of the Yardbirds’ Little Games, and another outtake in “Line of Least Resistance.”

Of most interest to those who’ve managed to collect the half or CD of this disc that’s come out before are the previously unreleased performances. Fidelity-wise, they’re not up to what would have been considered releasable in the late 1960s and 1970s, and sometimes the sound quality is actually pretty rough or rudimentary. Yet in common with many demos emphasizing guitar and voice, they have a window-to-the-soul feel that would have gotten lost with lots of production, or even much more production, considering these songs work best in a stark state. Although occasionally in an upbeat rock mood (“Try Believing”), more often he favored folky ruminations that verged on crossing the line from melancholy to spooky. “Collector to the Light” in particular sounds almost like a message from a hermit’s cave, with eerie reverb and miscellaneous faint shakes.

A few items are nothing more than sketches or lyric-less scats, but still attractive for their otherworldliness, especially “Roundalay,” which unwinds in jazzy circles as Relf hum-sings the kind of unpredictable minor-keyed melodies he favors. He wasn’t done with far-out experimentation, either, as the closing “Sunbury Electronic Sequence” emphasizes. As its harsh collage of numerous distorted effects goes on for nine minutes, placing it at the end was a good idea, in case you’re not in the mood for extended atonality.

For those needing something more accessible, both sides of his baroque-pop 1966 solo single “Knowing”/“Mr. Zero” are here, as is the yet rarer follow-up solo 45 “Shapes in Mind” (though in just one of the two commercially available versions; more on that in the next paragraph). So is a brooding folk piece from an April 1965 Yardbirds BBC broadcast, “All the Pretty Little Horses,” though that’s come out on previous official releases as “Hush-A-Bye.”

And here are the imperfections that drive label owners mad when reviewers point them out, but should be noted. This has one of the two versions of Keith Relf’s interesting 1966 single, “Shapes in My Mind” (the one that starts with an organ). Why doesn’t it have the other one that came out (which starts with a horn)? Both versions were included on another recent release on Repertoire, the Yardbirds’ Live and Rare box. And the 1968 Yardbirds outtake “Knowing That I’m Losing You” (later the basis of Led Zeppelin’s “Tangerine”) that includes a Relf vocal (the one that has been officially released is instrumental) would have made a great addition. It’s one of his greatest performances, and one of the Yardbirds’ best recordings from the Jimmy Page era. And it was likely unavailable for licensing, considering it’s never come out anywhere, though it’s been in unofficial circulation for quite a few years.

Relf has come in for his share of knocks from rock historians who find his vocals limited or lacking. I’ve always liked them a lot, however; what he lacked in power, he more than made up for in personality. They’re certainly an asset on this release, which is the kind of compilation that might only appeal to a pretty limited niche of fanatics, and be dismissed as marginal frivolity by many. And y’know what? Big deal. I’m one of those fanatics, and other fanatics will dig the hell out of this. For the story behind this release, read my article about this reissue, which includes material from a recent interview with Yardbirds Jim McCarty and Paul Samwell-Smith.

6. The Belfast Gypsies, Them Belfast Gypsies (Grapefruit). The Belfast Gypsies were a spinoff group from Them, including two members (singer/organist Jackie McAuley and drummer John aka Pat McAuley) who’d played on some of Them’s great mid-‘60s records. Their sole album, recorded in 1966 and initially issued by a Swedish label, was much like Them, but yet punkier and rawer, especially in the vocal department. To make a rough comparison, the Belfast Gypsies were to Them like the Pretty Things were to the Rolling Stones.

This was reissued on CD in 2003 with bonus tracks, and this edition is an upgrade, though there’s not much more material. Besides adding single and EP mixes of tracks from the LP, it also has an instrumental from a French EP (though the Belfast Gypsies were probably not involved in that recording). All of those tracks were on the 2003 CD, but this 2020 edition adds a couple of basic February 1966 demos (covers of Graham Bond’s “I Want You” and Bob Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”), which came out on a ten-inch back in 2005. The new CD also has extensive liner notes with some rare photos and memorabilia. Seven of the LP tracks were mastered from newly discovered master tapes, and the others were newly remastered.

All of these bonuses seem to make this the definitive edition, but a reservation has to be expressed. The opening track from the LP, “Gloria’s Dream,” noticeably slows down after the instrumental break. That didn’t happen on the 2003 CD, so this seems to be a flaw. Some labels and compilers don’t appreciate when things like this are pointed out for reissues that have been assembled with overall fanatical care. But like the brief skip in the Honeycombs collection reviewed earlier in this list, it’s something that needs to be noted for the very kind of fanatics who buy these kind of specialist reissues.

To risk losing a few more friends, it seems like the volume level is low on “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” (one of the greatest Dylan covers), though that doesn’t happen on my LP reissue. Mitigating the disappointment, the EP mixes of “Gloria’s Dream” and “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” don’t have these problems, and, to risk more wrath from those who might disagree, aren’t notably different from the LP versions at any rate.

I’m actually not that much of an audiofile, but all told, this would have ranked higher on this list had these quirks not jumped out at me. And the dozen LP tracks that are at the core of this release – the ones that really make it worth hearing – have long been easily available on reissues, as another reason why this doesn’t get an even higher ranking. The music is more important than imperfections, of course, and the Belfast Gypsies album is one of the best British Invasion obscurities, well worth hearing if you like first-wave British R&B/rock. The full, and very complicated, tale of the group is told in my lengthy story on the group in issue #23 (summer 2005) of Ugly Things magazine.

7. Fred Neil, 38 MacDougal (Delmore). As this was a pretty limited Record Store Day release in November, it might have passed unnoticed even by many Neil fans, although a wider CD/LP release is planned for 2021. These eight previously unreleased songs were recorded in 1965 in the apartment of John Sebastian and guitarist Peter Childs, both of whom played on Neil’s second album, the verging-on-folk-rock Bleecker & MacDougal. On both electric and acoustic guitar, Childs backed Neil’s vocals and guitar on this rather brief set, which lasts a little less than half an hour. Five of the songs also appear, in different studio versions, on Bleecker & MacDougal; one, “Sweet Cocaine,” would be done for his 1966 Fred Neil album; and the two others, the traditional folk tune “Once I Had a Sweetheart” and the African-American spiritual “Blind Man Standing By the Road and Crying,” don’t appear on any other Neil record.

Owing both to its brevity and prevalence of alternate versions, this is kind of like hearing bonus cuts to Bleecker & MacDougal that don’t happen to have been used on an expanded CD version of that album. But if you like this underrated folk-rock pioneer, it’s good and worth hearing, in part because Neil recorded just a few albums (and little of consequence after the 1960s). Although the studio versions are more definitive, there’s a pleasing informal vibe to the more familiar material, and the sound is pretty good. Fred’s melodic blues-pop-folk is affecting in these performances, as are his uniquely resonant low vocals, like a more tuneful and on-pitch Johnny Cash. From a historical point of view, the highlights are the two traditional songs that aren’t on other Neil albums. While not as striking as his original compositions, they’re fine spare interpretations, “Once I Had a Sweetheart” being perhaps most familiar to folk-rock fans through Pentangle’s superb version a few years later. He upped his characteristic dolefulness for the more somber “Blind Man Standing By the Road and Crying,” which concludes the set.

8. Neil Young, Archives Vol. II: 1972-1976 (Reprise). This mammoth ten-CD box could inspire a whole magazine’s worth of commentary from Neil-heads. I don’t use that kind of space on my best-of list reviews, so I’m sticking to some of the essentials. Almost half of the 131 tracks are previously unreleased, and many of the ones that were already available—particularly the 1973 live sets in Tuscaloosa, Alabama and the Roxy in Hollywood, as well as the mid-‘70s outtakes from the Homegrown album—were known primarily to Young fanatics. So although this does have a lot of material from mid-‘70s albums like Tonight’s the Night and Zuma that anyone who buys this set will already have, much of it’s unfamiliar, and likely brand new even to committed Young collectors. There are also a few Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young outtakes from their attempts at studio albums during this period.

It’s good to have so much available from a major performer, from peak or near-peak years. But what wasn’t issued at the time isn’t on par with the best of what he released between 1972 and 1976, nor should anyone expect that. Although it testifies to his sheer fertility as a composer, spinning off dozens of rejects that many songwriters would be happy to feature as highlights of their repertoire, there are reasons most of them weren’t selected for his LPs of the era. They’re not as striking or memorable as much of what made the cut. Even one of the best, the wistful 1972 outtake “Goodbye Christians on the Shore,” could have benefited from some trimming and more energetic execution. While it’s cool to hear some different arrangements of well known songs, like a much harder-rocking “Last Trip to Tulsa” (used on a B-side) and a live “The Loner” without orchestration, I wouldn’t put them on the level of the studio originals. Some rarities are more enticing on paper than they are through the speakers, like the rather forced guess-who-this-is-about piano ballad “Sweet Joni” (performed solo by Young at a 1973 concert). The same goes for the so-so rocker “Raised on Robbery,” a previously unreleased version of a Joni Mitchell song from the Tonight’s the Night sessions, which features Mitchell herself on vocals and guitar.

Here are a few observations that won’t be welcomed by all Young fans. He’s at his least impressive when he opts for a straightahead blues-rock groove; he could use bluesiness effectively, but the bluesiest stuff could be routine or even boring. The CSNY outtakes don’t hint that there was a buried masterpiece that never reached fruition as their plans for studio reunions fell apart for one reason or another. And overall Young wasn’t working at as high a standard as he had in his earlier solo years, with much of the best unissued material appearing on the disc with the earliest recordings (disc one, drawn from 1972 and 1973).

9. Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels, Sockin’ It to You: The Complete Dynovoice/New Voice Recordings(RPM). Mitch Ryder’s status as one of the great white soul-rock singers of the ‘60s is unquestioned. Like a lot of great rock and soul artists from the era, though, his albums were uneven. They’re certainly not as consistent a blast as a good best-of collection.

But if you’re reading this to consider whether a three-CD, 69-track of everything he did for the label that issued those big hits is worth buying, you probably already have a good best-of collection. You want to know: are Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels worth hearing in bulk? In a package with everything from the five LPs they did for Bob Crewe’s New Voice and Dynovoice labels, along with a few rare non-LP 45s?

Basically, yeah, but only if you’re willing to take a kind of bumpy Ryde. When the first LP leads off with ace covers of “Shake a Tail Feather,” “Come See About Me,” and “Turn on Your Lovelight”—not all of which automatically turn up on Ryder best-ofs—you’re primed for one of the best white R&B comps of all time. But Mitch and his Wheels couldn’t sustain that momentum—hardly anyone could—and there’s a good share of oft-done (sometimes overdone) soul standards that are more on the just-okay side. It didn’t help that they didn’t write original material, something that was always going to keep them out of the league of the best bands of this sort, like the Rascals. Ryder’s vocals are almost always fine, and the Detroit Wheels sometimes inspired, but some of the arrangements are so-so.

The Wheels, whose ultra-tense grooves were never mixed as high as they could or should have been in Crewe’s productions, started to fade more and more into the background as time went on. Crewe partially solved the problem of original material by writing or co-writing most of Mitch’s third album, Sock It To Me!, including the hit title track. Usually it spells trouble when a producer takes such a firm rein. But actually the LP wasn’t bad pop-soul-rock, even when Ryder went afield from his usual forte into almost West Side Story-ish drama (“A Face in the Crowd”) and a sort of soulful Jay & the Americans melodrama (“Wild Child”). He also handled “Walk on By” well, though “Soul Fizz” is an oddity—Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels with a Ryder-less instrumental?

Crewe took his client into more questionable territory with Sings the Hits, which is just a bunch of old—actually just a year or two old—tracks that he remixed and/or overdubbed, throwing in a couple obscure 45 sides that made their first appearance on LP. Again this isn’t as gruesome you might brace yourself for, with the overdubbed horns making for interesting contrasts with the more familiar versions without getting too overbearing. The originals on which you can hear the Detroit Wheels better are, naturally, superior. And they’re all elsewhere on this box, so you don’t have to gnash your teeth over a rip-off.

Then, in true docudrama good-deal-turns-bad fashion, Crewe steered Ryder toward a Wheels-less solo career on What Now My Love, cutting Mitch on some pop standards in the process. This sounds like your basic recipe for disaster, but at the risk of seeming contrarian, it really isn’t as bad as you’d predict. It’s not all standards, with some workmanlike soul and rock oldies covers. And Ryder actually wasn’t so bad at the standards, making a reasonable job of Jacques Brel’s “If You Go Away (Ne Me Quitte Pas)” and going into some impressive (if admittedly rather ludicrous) vocal gymnastics on the modest “What Now My Love” hit. This wasn’t Mitch’s forte, however, and by the end of the ‘60s he was both free of Crewe and hitless.

Also on this anthology is his fine cover of “Too Many Fish in the Sea,” which despite being a fair-size hit was only on the All Mitch Ryder Hits compilation, not one of his regular LPs. Far rarer are seven tracks from mostly post-Wheels non-LP 45s (plus a brief spoken radio spot) that close out disc three, all obscure save possibly “Joy,” which just missed the Top Forty. These were for the most part just fair, though Ryder’s vocals were almost always impressive, and not mailed in even when it was obvious the material wasn’t what he deserved.

The notable exception is the funky “Ring Your Bell”—the one track from the Crewe years that Ryder wrote. It slinks along with a sly confident vocal and cool organ-horn blend, though it’s too bad it (and a few of the other non-LP tracks) has a slight wobble, as if the original source wasn’t used or isn’t pristine. “Ring Your Bell” proved Ryder could develop into a good writer. But with Crewe at least, he wouldn’t have the chance. (This review appeared in the summer 2020 issue of Ugly Things.)

10. The Idle Race, The Birthday Party (Grapefruit). The term wasn’t around back then, but the Idle Race were among the premier exponents of “toytown” psychedelia—story-songs with more than a hint of childhood longing/fantasy, done with enough quirky lyrics and production sophistication to keep it out of the children’s bin. Known (if at all) to the larger public as the first group in which Jeff Lynne recorded LPs, they didn’t make much of a dent on either the charts or the underground before Lynne joined the Move. From 1968, The Birthday Party was their first album, here issued as a two-CD package including the stereo and mono versions of the original LP, along with a bunch of non-LP singles and alternate versions.

It’s easy to draw comparisons between this and late-‘60s work by bigger and better bands, particularly the Beatles and the Move. The Idle Race, and particularly chief songwriter Lynne, drew heavily on the most lightweight la-la aspects of Paul McCartney’s work, with some of the eccentricity of chief Move composer Roy Wood. Their first single (oddly unissued in the UK), in fact, was a cover of the Move’s “(Here We Go Round) The Lemon Tree.” Almost everything else here was written by Lynne, with fellow Idle Racer Dave Pritchard pitching in a few songs.

As long as you don’t set your expectations for an equivalent to Magical Mystery Tour or the Move’s flurry of ‘60s hits, The Birthday Party’s an enjoyable if slightly twee set of very British pop-rock, even if it sometimes sounds like a kiddie TV show soundtrack gone off the rails. (Lynne amusingly, and not wholly inaccurately, once described the Idle Race as “a cross between George Formby and something or other.”) The tales they tell aren’t especially deep, but they’re fairly witty and unremittingly bouncy, with more than a hint of the helium harmonies that would be a trademark of Lynne’s subsequent projects. Modest orchestration and weird effects take some of the cuts into relatively adventurous arrangements. In view of Lynne’s later fame, it’s tempting to dub them a low-budget, less pretentious foreshadowing of some of his work in the Electric Light Orchestra.

The Idle Race never had hits, but a few of these ditties sound like they could have been with a bit more production/promotion oomph. “Skeleton and the Roundabout” feels like a ride on an arty merry-go-round; “Follow Me Follow” is a rockaballad that will appeal to anyone who likes McCartney facsimiles of the kind Emitt Rhodes devised; and “Morning Sunshine” has very Beatlesque guitar swoops. The non-LP B-side “Knocking Nails into My House” injects a welcome bit of ominous narrative into the mix in its play-by-play detail of a foreclosure. It’s the strongest track here, though not the most typical. Nearly as strong, yet anomalously moody and hard-rocking, is another non-LP flip, Pritchard’s “My Father’s Son,” which ends with a most uncharacteristic blast of feedback.

As the Grapefruit label (and the Cherry Red family to which it belongs) has compiled a lot of ambitious multi-disc sets, it’s a little surprising and perhaps disappointing it didn’t opt to do one collecting all of the Idle Race’s Lynne-era output. That would include not only the group’s second LP (1969’s more mature, yet less impressive, Idle Race), but also a wealth of late-‘60s BBC sessions. Maybe that will be wrapped up with an expanded edition of Idle Race. It would be a welcome supplement to this release, whose 24-page liners include a heap of vintage graphics and comments from Lynne and Pritchard. (This review appeared in the summer 2020 issue of Ugly Things.)

11. Various Artists, Crawling Up a Hill: A Journey Through the British Blues Boom 1966-71 (Grapefruit). Like Grapefruit’s numerous other three-CD curations of major British rock styles spanning the mid-‘60s to the early ‘70s, this mixes big names with cult names and unknowns. John Mayall, the Yardbirds, Fleetwood Mac, Ten Years After, Free, Jeff Beck—they’re all here, usually represented by one of their deeper cuts. So are notable but less popular figures like Graham Bond, Duster Bennett, Savoy Brown, Taste (with Rory Gallagher), the Climax Chicago Blues Band (as they were known at their outset), Stone the Crows, and Medicine Head. And there are early Fleetwood Mac-related solo efforts by Christine Perfect and Jeremy Spencer, as well as Peter Green taking a lead vocal with the Brunning Sunflower Blues Band, led by original Fleetwood Mac bassist Bob Brunning.

That alone’s a choke-a-horse list. But the bigger attraction for collectors is the wealth of tracks by acts only known to those who pore the listings of specialist reference books. The Zany Woodruff Operation (who did a fair cover of the early John Mayall single “Crawling Up a Hill” that gives this comp its name), Shakey Vick, Jaklin, Frozen Tear, Angel Pavement, Levee Camp Moan, Red Dirt, and Blue Blood—it’s doubtful more than a few dozen or so British blues hounds are familiar with all those names. Plenty of the tracks are taken from way-rare LPs and 45s, as well as some recordings that were privately pressed or unissued at the time.

The span is certainly wider than the most famous British blues anthology, Sire’s 1973 double-LP History of British Blues (which includes a good number of the same top names, though there’s no overlap in actual songs). As much as we get our jollies from having a lot of material in one place, the more important factor is how good a listen it makes. And it’s pretty good and diverse, progressing from ace cuts with roots in the mid=’60s British Invasion (Mayall’s “All Your Love” with Eric Clapton, Bond’s non-LP single “I Love You,” a live “I’m a Man” from the Yardbirds’ Jimmy Page lineup) to purer blues and early-‘70s hard rock-flavored outings. The relatively little-heeded British acoustic blues scene gets some airing too, with efforts by Anderson Jones Jackson (featuring future Folk Roots editor Ian A. Anderson), one-man-band Bennett, Jo-Ann Kelly, and Mike Cooper.

The British blues boom—a more purist-minded, less pop-oriented movement than the mid-‘60s explosion of UK R&B-rock bands spearheaded by the Rolling Stones, Pretty Things, Animals, Yardbirds, and Them—has come in it for its share of mockery for being too stodgy, imitative, and bombastic. There’s some of that here, but not too much, and some of the selections venture beyond the straight blues format into more flexible (and, usually, interesting) territory. The Christine Perfect Band’s “It’s You I Miss,” for instance, is a real highlight, and not just for its rarity (broadcast on a November 1969 radio session, this Perfect composition somehow wasn’t included on her 1970 solo LP). Brooding, minor-keyed, and huskily intoned, it’s a real cool tune that will even appeal to those who don’t care for the Fleetwood Mac records after she joined the band.

Some of the other rarer relics show the more workmanlike British blues groups in their best light. The Climax Blues Band’s “A Stranger in Your Town” is fine slide blues variation on “Rollin’ and “Tumblin’” that sounds a bit like a subdued Yardbirds. Savoy Brown weigh in with a ferocious, menacing live January 1970 version of “A Hard Way to Go.” And there are some goodies from names not especially identified with the blues boom. Badfinger’s Pete Ham and Tommy Evans add spooky background vocals to Heavy Jelly’s eerily plodding blues-rocker “Take Me Down to the Water,” written and sung by Jackie Lomax. Linda Hoyle, lead singer of the not-terribly-well-known band Affinity, offers a credibly hard-hitting cover of Nina Simone’s “Backlash Blues.”

And there are some decent tracks by the no-names. Red Dirt’s “Time to Move” sounds rather like Jethro Tull at their earliest and bluesiest. Icarus put a bit of jazzy melody and psychedelic organ into “There’s An Easy and a Hard Way of Living,” which like some of the other better material here is better described as “bluesy” than “blues.” There weren’t many Alexis Korner covers, but Jaklin offer a decent rocky version of one of his best originals with “The Same for You.”

Crawling Up a Hill is also more inclusive than many a similar comp might be, drawing in more or less straight blues offerings from groups that didn’t do much of that thing, like the Deviants (“Charlie”), Love Sculpture (“Wang Dang Doodle”), and even Mungo Jerry (“The Sun Is Shining”). There are also a few irreverent parodies, to remind us that not everyone in Britain took blues purism so seriously. The Bonzo Dog Band’s “Can Blue Men Sing the Whites?” is the most familiar of these, and it’s here. But so are Liverpool Scene’s “I’ve Got Those Fleetwood Mac Chicken Shack John Mayall Can’t Fail Blues,” Jeremy Spencer’s “Mean Blues,” and the Downliners Sect’s rather frivolous Tolkien-blues hybrid “Lord of the Rings.”

Are there significant omissions, whether for licensing or other reasons? Sure, starting with the Rolling Stones, who went into pure blues on some of their late-‘60s recordings. If we’re talking hard rock acts who owed a lot to the blues, Led Zeppelin’s not here either, though Robert Plant’s the featured vocalist on Korner’s “Operator.” There probably aren’t too many people who’d get up in arms over the absence of the Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation, Keef Hartley, or Dave Kelly. But it’s a shame there’s nothing by Duffy Power, one of the finest and most creative cult British bluesmen, who did some of his best and bluesiest stuff during this period.

The small-print, 40-page liner notes by David Wells are jam-packed with info about each track, along with plenty of period record sleeves, pictures, and graphics. There are many more British blues boom highlights besides the ones fit onto this nearly four-hour set, but it surpasses History of British Blues as the best survey of its sort. (This review appeared in the summer 2020 issue of Ugly Things.)

12. Robbie Basho, Songs of the Great Mystery (Real Gone). Similar in mood if not exact style to John Fahey (for whose Takoma label he recorded in his early career), guitarist (and occasional pianist) Robbie Basho constructed haunting music often utilizing unusual minor-keyed melodies, edgy strumming, and a general stormy-cloud aura. He recorded fairly prolifically from the mid-1960s through the mid-1980s without achieving much in the way or sales or renown, even compared to a cultish figure like Fahey. So prolific was his output, in fact, that unreleased material continues to pour from his vaults, including this previously unreleased album. Recorded for Vanguard Records in 1971 or 1972, it’s actually a little more than a single LP (at least by vinyl-era standards), adding up to 55 minutes of music with the addition of an alternate take.

Songs of the Great Mystery isn’t too drastically different from other Basho records I’ve heard, which can serve as either a caution or a recommendation. His rather downcast music isn’t for everyone, and his shaking-leaf vocals definitely aren’t for everyone. He usually concentrated on instrumentals, but sings more often than usual in this set, often referencing Native American culture and images of thunder in his lyrics. On “Thunder Love,” you even wonder if he influenced Bruce Springsteen’s “Thunder Road,” though that seems extremely unlikely. Interesting lyric from “Laughing Thunder, Crawling Thunder”: “America, god has shed his blood on thee.”

Even if it doesn’t stand out as one of his best outings, and some of the songs are fairly similar to each other (and other Basho recordings on different albums), I like the idiosyncratic atmosphere he creates enough to recommend it. His vocals aren’t that great, but at least suitably complement the eerie guitar work and melodies, which are the main assets of this vault find. Also good are the comprehensive liner notes by Glenn Jones, which feature a wealth of detail and description for a batch of tracks whose recording dates aren’t even certain.

13. Robbie Basho, Song of the Avatars: The Lost Master Tapes (Tompkins Square). If you thought nearly an hour of Basho outtakes was specialized, it’s put to shame by this five-CD compilation of previously unreleased material, spanning the guitarist’s entire career. (Technically speaking some of the tracks came out slightly earlier on a Record Store Day LP compilation.) Known to have existed for years before this anthology was assembled, this stretches from approximately the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s. “Approximately” is the necessary qualification because there weren’t dates on these tapes, although the songs were titled. Experts involved in the set’s production could make some reasonable estimates as to a rough order in which the material was recorded, but the exact times and dates will never be known.

This collection does in a way serve as a career retrospective of sorts, albeit one that doesn’t have his very best recordings, as those were featured on the numerous LPs he issued during his lifetime. If you do like Basho, however, this Basho-in-bulk has a few notable things going for it. A lot of it’s almost or as good as what made it onto his official releases. The tracks don’t just present different versions of songs that are already available, although a few passages here and there were heard in altered form on his albums. The sheer range of styles is also impressive, from the raga-avant-folk that made his biggest mark to devotional music and, on what are probably some of the earliest recordings, blues.

Of course this isn’t for everyone, and maybe not even for all Basho fans. Be aware that quite a few songs are vocal numbers, which are less beloved by most of his listeners than his instrumentals, as they’re (to quote admirer Pete Townshend) “a cross between a kind of a cantor in a synagogue, the mullah calling from the tower for prayers in Islam, and a kind of a street singer. But also an opera star.” On some selections, he switches from guitar to eerie piano. The final track offers a sixteen-minute cantata and features some other singers.

Overall I’d put this at something of a tie with the previous entry on this list, but acknowledge that five discs is a much greater investment of time and money than a single CD. So this might be a little less approachable, and is certainly a less uniform listening experience, than Songs of the Great Mystery. But it’s undeniably more diverse, and recommended just as strongly to Basho fans.

14. Various Artists, Tape Excavation (Independent Project/P22). Even if you’re the kind of collector who gets in line for Record Store Day releases at dawn, you’ll be frustrated by trying to acquire this LP-only release if you don’t already have it. It was available only as part of the 350-copy deluxe limited edition of the book Savage Impressions: An Aesthetic Expedition Through the Archives of Independent Project Records & Press, which is already sold out. The book compiles artwork, often using distinctive letterpress design, by Bruce Licher for numerous records, posters, stamps, and other media since 1980 (see review in my post for best 2020 rock history books). The LP compiles fourteen previously unreleased tracks from various Licher musical projects spanning 1980 to 2019, including material from his most famous band (Savage Republic); pre-Savage Republic outfits Project 197, Bridge, and Final Republic; and post-Savage Republic projects Scenic, Lanterna, Lemon Wedges, Bank, and SR2, along with post-Savage Republic Licher solo recordings.

Highly worthwhile on its own terms, Tape Excavation’s selections are actually of similar quality to Licher’s previous official releases, even if the fidelity and polish might not be as high on a few tracks (particularly the earlier ones). Although it covers four decades, there’s a continuity in the eerie instrumental textures, which both use conventional instruments (especially Licher’s unusually tuned guitar) and blend them in unconventional ways. The earlier efforts on side A bear some traces of early-‘80s post-punk dissonance, yet are likely to appeal to people who don’t usually like post-punk, at least if my own tastes are an indication. There’s even some appealingly cheesy new wave keyboard on Final Republic’s “Chase,” though the same group was responsible for the foreboding waves of overlapping reverb dominating “The Unknown.”

Licher focused more on sort of post-punk equivalents to surf music with elements of psychedelia and middle eastern melodies as time went on. His pair of 1997 solo demos are of special note; “Cedar” is worthy of exotically dreamy Ennio Morricone-like soundtracks, and “Tundra” can’t help but sound like an end-of-the-century takeoff on the Byrds’ “Why.” The later excursions on side B might be less edgy and frenetic than his ‘80s endeavors, but maintain his knack for atmospheric instrumentals that are more mature yet not at all wimpy. According to the detailed liner notes, Licher went through dozens of boxes of recordings to cull these tracks, and if even a small percentage of these approach Tape Excavation’s standard, a series of archive releases would be welcome. So would a standalone edition of Tape Excavation itself on LP and/or CD, though given its use as an extra for a deluxe edition, that probably can’t be counted on soon.

15. Jimi Hendrix, Live in Maui (Legacy). If you’ve seen the jaw-droppingly bad film Rainbow Bridge, you know its only redeeming feature is the 17-minute segment in which Hendrix, accompanied by Mitch Mitchell and Billy Cox, play live to an audience of a few hundred in a field in the Maui hills. It’s something of a miracle that a good-sounding album of the July 30, 1970 concert is now available, since the environment wasn’t too conducive for good fidelity. That’s evident in the film, where you see foam covering the microphones to cut down on the wind. But this two-CD set has reasonable sound and enthusiastic, if somewhat loose, performances. Since it’s one of the final US concerts he gave before dying less than a couple months later, it’s also of significant historic value.

As a record, however, it’s not all that different from a couple live albums taped a month earlier (Live at Berkeley) and a month later (Live at the Isle of Wight). The set list is pretty similar, though this has a few songs (“In from the Storm,” “Hear My Train A-Comin,’” “Villanova Junction”) that aren’t on Live at the Isle of Wight. Like that previously available live material, it shows Hendrix starting to ease back toward more focused songwriting on tunes like “Dolly Dagger,” but also prone toward sprawling improvisation. While it’s not too noticeable, purists should know this doesn’t present the show in its entire unvarnished state. Back in 1971, Mitch Mitchell overdubbed drums on the songs featured in Rainbow Bridge, and the original tape did not capture a few numbers in their entirety.

These CDs are packaged with a Blu-ray documentary, Music, Money, Madness…Jimi Hendrix in Maui. The Blu-ray is reviewed separately, in my list of 2020 rock history films.

16. Phil Ochs, The Best of the Rest: Rare and Unreleased Recordings (Liberation Hall). All but three of the twenty tracks on this archival compilation were recorded as publishing demos for Warner/Chappell in 1964/1965. Plainly recorded with just Ochs’s voice and acoustic guitar, these include some songs from his mid-‘60s Elektra LPs, some of them among his better and most famous, like “Love Me, I’m a Liberal,” “Canons of Christianity,” “I’m Gonna Say It Now,” “Bracero,” and “Here’s to the State of Mississippi.” It also has some pretty obscure ones that didn’t make the LPs he issued in his lifetime, like “City Boy,” a very good lilting tune that seems to mark one of his first excursions into non-protest/social commentary writing, “I’m Tired,” and “Colored Town.” And three of these songs have never been on any prior Ochs release (and there are many Ochs releases, especially when you count collections of material he didn’t issue during his lifetime), including “Sailors and Soldiers,” “I Wish I Could Have Been Along,” and “Take It Out of My Youth.”

Also featured as “bonus tracks” are three additional items. “The War Is Over” is taken from a November 20, 1967 broadcast on New York’s WBAI. With joyous background whoops and quite different lyrics from the studio version, it’s the highlight of this CD. Of more purely historical interest, though worth hearing, is a 1970 rehearsal take of his last great composition, “No More Songs,” which has an almost classical feel as the tune is worked out on piano. From 1969, the less memorable “All Quiet on the Western Front” was previously only known via a couple incomplete live versions.

It’s good to have more Ochs in good sound quality, even if the arrangements are rudimentary. Still, this is pretty peripheral to his core work, which is better appreciated on the music he released while an active performer. In his early days, the best of his material was selected for his LPs (“City Boy” being a curious oversight); some of the compositions here are rather generic Ochs in comparison. The packaging is also not clearly annotated. Just six of the songs (including all the non-Warner/Chappell demos) are designated as “previously unreleased,” but I’m not aware of anywhere else these tracks have appeared, and I have a lot of Ochs in my collection.

My guess is that the three mid-‘60s demos marked as “previously unreleased” are the three instances where there are no other versions of those specific songs, and that in fact everything here is previously unreleased. Even in the cases where some songs also appear on the outtakes compilation A Toast to Those Who Are Gone, these seem to be different versions; the performance of “City Boy,” which has a piano on A Toast to Those Who Are Gone, is definitely a different recording. The liner notes do not comment upon if or where any of the tracks were also issued. This is a specialist release geared toward intense Ochs fans, who deserve more than the ambiguous vagueness associated with bootlegs, though this is definitely authorized, as it was produced by his brother (and manager) Michael Ochs.

17. Simon & Garfunkel, Live at Carnegie Hall 1969 EP (Legacy). A low-key streaming-only release that even some Simon & Garfunkel fans might have missed, this has four songs from their Carnegie Hall shows on November 27 and November 28, 1969. A few other recordings from November at Carnegie Hall have come out elsewhere, but these were previously unreleased. Why only four tracks were dispensed, and only via streaming, is a question only the record label and the duo can answer. But as modest pleasures go, it’s pretty good, if containing no big surprises. Included are acoustic versions of “The Boxer” and, a couple months before their official release on the Bridge Over Troubled Water LP, “So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright,” “Song for the Asking,” and “Bridge Over Troubled Water” itself. Art Garfunkel’s just backed by piano on the last of these. The way the catalog business goes, it wouldn’t shock me to see a full-length release from these shows in the future, but for now, it’s all there is.

18. Various Artists, 17 from Morden (Top Sounds). In the 1960s, the Morden Park Sounds Studios of R.G. Jones in London recorded hundreds of British rock groups, most notably the Yardbirds for some of their earliest studio work. Many of the groups that passed through there didn’t release records, or only put them out in extremely limited editions. This compilation has seventeen such tracks, none of them by acts that are even reasonably well known to collectors; none had musicians that went on to fame, though a couple did put out discs on bigger labels. A few cuts are even credited to “unknown,” as the musicians remain unidentified. This is only going to appeal to hardcore British Invasion specialists, especially as a good number of the songs are covers of well known tunes.

But if you are that kind of ‘60s British rock nut, like me, you’ll find this an enjoyable swipe of groups that straddled the line between amateur and professional, even if some of its value is documentary as well as musical. All of the groups have brash energy, usually but not always on the R&B/rock side of things. The Cindicate (not to be confused with the Syndicats, with whom Steve Howe made records in the mid-’60s) stand out for their wild rendition of John Lee Hooker’s “I’m Mad Again,” possibly inspired as much or more by the Animals’ cover as the original. Stretched out to five minutes with extended instrumental raveups, it’s the best thing here, even if it sounds like a wind machine’s blowing in the background. The Night Society’s brooding “Play Around with Love” is the best original, in part because it at least tries to do something beyond the standard R&B format, sounding a little like a marriage of the minor-keyed melodies and harmonies of the Zombies with mod rock energy. If nothing else here is too memorable, it’s fun to hear while it’s spinning, and captures the energy of British youth in the wake of the great British beat explosion. And that, combined with thorough illustrated liner notes, is enough to put it on this list.

19. Various Artists, Sumer Is Icumen In: The Pagan Sound of British and Irish Folk 1966-75 (Grapefruit). This 60-song triple disc indeed features British Isles folk, usually of the mildly folk-rock-leaning sort, from the mid-‘60s through the mid-‘70s. It’s a little unclear what fits into the “pagan sound” theme. Much of the material is drawn from traditional folk sources, or clearly inspired by traditional folk sources, that’s colored by myth, magic, and exotic legend. Some of it only indirectly reflects this. Should we even keep score as to what might qualify?

It’s better just to take this as the latest installment of a series of quality three-CD sets on the Grapefruit label devoted to UK folk-rock (also including, on this set, music from Ireland). Preceded by 2015’s Dust on the Nettles and 2019’s Strangers in the Room, all have been overseen and extensively annotated by David Wells. All have a good balance of tracks from the most famous folk-rockers of the region and the most renowned mid-level and cult such artists. There are also obscurities who only put out private pressings, or never even managed to release anything while active.

Sumer Is Icumen In (sic) doesn’t duplicate any selections from the other two collections, but features a lot of the same artists. The heavyweights are here: Fairport Convention, Pentangle, the Incredible String Band, Steeleye Span, the Strawbs, even a 1975 cut by Mike Oldfield. So are fairly successful acts who didn’t quite make the same impact, like Shirley Collins & the Albion County Band, the Young Tradition, and the Third Ear Band. Then there are plenty who get enthused about in specialized reference books, like Oberon and Stone Angel, even if most people have yet to hear them. And there are names that even those who know the likes of Mellow Candle will probably find unfamiliar, like Shirley Kent and the Minor Birds.

Few genres of the era were as earnest as this strand of British folk-rock. Or as reticent: there’s often an air of devout restraint, whether electric instruments are used or not. It’s not the most varied or exciting stuff, but suits the mood when you want something somber with a touch of the eerie or strange, most often supplied by dabs of unusual instrumentation. The Strawbs’ “Canon Dale”—an alternate version, though the liners aren’t specific about the exact source—is a standout in that respect, backing ominous harmonies with sitar and Rick Wakeman’s gloomy organ.

There’s not much in the way of hooky tunes here, and some of the more memorable offerings arise when the set goes outside the folk-rock boundaries for tracks by rockers with a folk-rock influence. Traffic’s “John Barleycorn” is not just the most famous effort here; it’s the best. Nearly as good is Fairport’s “Tam Lin,” though it’s hard to imagine that anyone with an interest in this style doesn’t already have it in their collection. Less celebrated but welcome contributors from the rock scene include Kevin Coyne, Mighty Baby, Curved Air (whose “Elfin Boy” is effectively spooky), and Marc Bolan, represented by his 1966 demo “Eastern Spell.”

Even if you count this as part of a series and not just on its own, there are bound to be omissions that will upset some enthusiasts. Now that Ireland’s included in the survey, it’s too bad there’s nothing from Clannad’s fine 1973 debut album, which is far more influenced by Pentangle-styled folk-rock than anything else they issued. Maybe that LP didn’t have anything pagan enough; much of it was sung in Gaelic, so it might not be easy to tell. More obviously, there’s still no Donovan, the only global superstar with some affiliation with this movement. Perhaps licensing is the obstacle.

Of course, it’s easy to access Donovan’s catalog, or Clannad’s for that matter. Where else can you get the likes of Midwinter, Magnet, and Amber, who didn’t even have records? And on the same anthology as outtakes by Bridget St. John, the Sallyangie, and Mighty Baby that you might not yet have hard? For all but the very rare collector who has most or all of this material, it’s a good way to make deep dives into the peak era of British folk-rock, with some familiar faces along the trail to improve the overall listening experience. (This review will also appear in a future issue of Ugly Things.)

20. Carla Thomas, Let Me Be Good to You: The Atlantic & Stax Recordings (1960-1968) (SoulMusic). Carla Thomas was one of Stax’s most consistent hitmakers in the 1960s, and by far the label’s most successful woman performer in that decade. This four-CD set has all of her recordings on Stax and Atlantic from 1960 to 1968, the 94 tracks including everything from her albums and singles during that period. There are also five cuts from the Stax/Volt Revue’s 1967 live albums in London and Paris, and her duets with Otis Redding and father Rufus Thomas. Add the booklet’s 8000-word liner notes, with first-hand quotes from a few who were there (though not Carla herself), and it’s a complete document of Thomas’s prime.

Complete documents don’t usually mean quality that’s as consistent as best-of compilations, and that’s the case here. Her LPs, in common with many ‘60s artists, had a lot of covers of hits and standards. Her girl group-crossed-with-Memphis-soul voice guarantees that none are poor, but it’s hard to get too excited about routine versions of the likes of “What the World Needs Now,” “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” “Let It Be Me,” “I Fall to Pieces,” and “Birds & Bees” (with Rufus Thomas). As much some historians take pains to differentiate Stax from Motown, a few cuts are obviously derivative of the early Supremes, and “Something Good (Is Going to Happen to You)” can’t help but recall Stevie Wonder’s “Uptight.”

While the best of her sides from this time were compiled back in 1994 for Rhino’s 22-track Gee Whiz: The Best of Carla Thomas, this far more extensive collection has its rewards if you’re a big Thomas fan and/or heavily into the Stax sound. That set only had one Carla-Rufus duet, and just a couple Thomas-Redding duets (including their big hit “Tramp”). This has ten Carla-Rufus tracks (a couple credited to Rufus & Friend), including the 1960 single on Satellite that marked her first appearance on disc. It also has the entire King and Queen album pairing Thomas and Redding, though that has its share of covers of familiar tunes like “Tell It Like It Is,” “Bring It on Home to Me,” and “It Takes Two.”

Although the many non-best-of singles can take on a slightly generic Stax feel, there are some good efforts that will be new to lots of listeners who don’t have complete collections of records on the label. Some have a satisfyingly gutsy feel, like the brassy cover of “Little Red Rooster” and the mid-‘60s B-sides “Every Once of Strength” and “Stop Thief.” The five live Stax/Volt Revue songs have a rawer edge than the more polished studio productions, including renditions of her biggest hits (“Gee Whiz!,” “B-A-B-Y,” and “Let Me Be Good to You”) along with covers of “I Got My Mojo Working” and (less impressively) “Yesterday.”

Just two of these recordings are from 1968, and as Thomas kept recording for Stax until 1972, it’s not a complete overview of her work for the company. Most would agree this covers the best of her time with the label, however. Although a lot of this material’s shown up on other reissues and Stax singles boxes, this is an overdue anthology putting everything of hers from these years in one place. (This review will also appear in a future issue of Ugly Things.)

21. Various Artists, Living on the Hill: A Danish Underground Trip 1967-1974 (Esoteric). Every country had its psychedelic/progressive rock scene in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, and Denmark’s small size didn’t keep it from producing lots of records to go with it. Many of them are sampled on this 30-track, nearly four-hour triple CD, plenty of which should be unfamiliar to all but the most dedicated Scandinavian rock hoarders.

Although some of these groups managed to get their discs released outside their native country, really only Savage Rose made much of an impact on English-speaking audiences, what with a few US LPs, Rolling Stone reviews by Lester Bangs, a Jimmy Miller-produced album, and even an appearance at the 1969 Newport Jazz Festival. Bands like Burnin’ Red Ivanhoe (whose 1971 album W.W.W. made it onto John Peel’s Dandelion label), Young Flowers, and Culpeper’s Orchard have gained some modest recognition beyond their homeland in the twenty-first century. Yet for the most part, most of the names on this anthology are pretty unknown in comparison.

Is there a specifically Danish tone to these efforts? Not especially, most of the tracks bearing a heavy British prog influence. Lengthy (not infrequently, too lengthy) soloing abounds, and there’s plenty of organ, sometimes ethereal and classically shaded, to go with the guitar workouts. There are echoes, sometimes loud ones, of major UK prog stars like Pink Floyd, the Nice, and ELP, as well as subtler traces of King Crimson, the Moody Blues, Soft Machine, and the like. There’s a one-or-two-steps-removed-from-the-source feel that adds a bit of strangeness, as though the formula’s been a bit altered or tampered with, though almost all it’s sung in English.

At its best, the cuts lean as much or more toward psych or prog. Beefeaters’ instrumental (aside from some inscrutable mumbling) “Night Flight” (the sole 1967 track) is as much ghostly psych-garage as prog. Day of Phoenix’s “Tell Me” is rather like early Fairport Convention, unsurprisingly so since it’s a cover of the Dave Cousins composition “Tell Me What You See,” which was on the album Sandy Denny recorded with the Strawbs before joining Fairport. Burnin’ Red Ivanhoe’s “Avez Vous Kaskelainen?” is a hypnotic, propulsive instrumental driven by the kind of weedy organ favored by very early Soft Machine. Despite its 1969 release date, the same band’s “Jingle Jangle Man” sounds a little like the heavier parts of David Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World. That leaves the intriguing, if unlikely, possibility that it actually influenced Bowie.

Too often, however, these outings succumb to bombast. Some of the soloing’s as tedious and overlong as any pedestrian British blues-rock band managed. Roundabout riffs are tossed off with flash, but little hooky melody or soul. On Burnin’ Red Ivanhoe’s “Ksilioy,” the best and worst of Danish psych/prog collide, as the first three minutes of blissful harmony-driven walk-through-the-forest power pop-cum-psych would fit snugly onto the original Perfume Garden compilations back in the ‘80s. But don’t get too comfy, as it then runs aground by repeating the same nagging riff for a full seven-and-a-half minutes. This isn’t daring experimentation; it’s being rude to the listener. I even wondered if my CD player had gotten stuck, but no such luck.

As a more general observation verging on criticism, few of these artists project much of an identity, even if their technique is almost on par with bigger British names. Admittedly the one, two, or three songs you get from each featured band aren’t enough for drawing definitive conclusions. Still, you can immediately tell it’s Savage Rose and no one else from the sound of the swirling organ on “Tapiola,” and Annisette’s freaky voice on “Long Before I Was Born.” No other group here puts such a distinctive stamp on their work.

If you’re in the mood for sounds from prog’s heyday that are a little off-kilter from the norm, however, this has its share of haunting passages and odd ideas. It’s best heard one disc at a time, though, to steer clear of getting overwhelmed by too much somber, ponderous riffage and winding near-epics at once. Esoteric’s dependably in-depth 36-page booklet has plenty of info on the bands, as well as vintage record sleeves and photos. ((This appeared in the winter 2021 issue of Ugly Things.)

22. Neil Young, Homegrown (Reprise). One of the most famous unissued albums of all time, Homegrown was originally planned for release in 1975. Famously, at least among Neil Young fans, it was replaced by another unreleased LP, Tonight’s the Night, after he played both for friends back to back and came to the decision/realization that Tonight’s the Night was stronger. Young’s been more active than almost any major musician in putting out vault material in the twenty-first century, and Homegrown finally made its official bow in 2020. Like many if not most unreleased albums whose mystique grows through the years, its belated unveiling is kind of underwhelming. It’s a mostly (though not exclusively) low-key collection emphasizing his mellower folk-country side.

Not everything fits that description, especially “Florida,” whose weird combination of inscrutable stoned rap with eerie musique concrete puts it on the fringe of the avant-garde. The basic blues “We Don’t Smoke It No More” seems similarly out of place, or almost as if Young is deliberately tweaking his audience with songs that are half-jokes. But the greater hindrance is that most of the tracks are sort of generic mid-‘70s Young, which is admittedly better than most mid-‘70s artists were at their best. Also, the best songs have been available for forty years or more on other releases, including the country tune “Love Is a Rose” (on Decade), “Star of Bethlehem” (on American Stars ’n Bars), and “Little Wing” (on Hawks & Doves). Homegrown was also issued as disc seven of the box set Archives Vol. 2: 1972-1976, which is reviewed elsewhere on this list.

23. Bob Dylan, 50th Anniversary Collection 1970 (Columbia). 1970 wasn’t one of the most illustrious years in Dylan’s career, but it was a productive one, if you’re just going by the quantity of music he recorded. Outtakes from this year have appeared elsewhere, especially on The Bootleg Series Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait (1969-1971). This very limited edition three-CD set isn’t part of his bootleg series; it’s part of his copyright extension series, with volumes issued near the end of most years as a fifty-year deadline approaches. There are no less than 74 previously unissued tracks here, although most of these are alternate versions of songs from his 1970 New Morning album, or (far more often) tossed off covers and revisitations of compositions he’d already put on his records. These go all the way back to “Song to Woody,” which he put on his debut album.

These aren’t any great shakes, and not just because these are outtakes. The New Morning songs weren’t too good in any version, with the exception of “If Not For You” (six versions are here) and maybe “Went to See the Gypsy.” It’s kind of interesting, though, to hear him running on half-or-less empty or autopilot, bereft of most of the inspiration he’d flashed in the 1960s, but casually keeping on going, even if it feels a little like going through the motions. There are lots of covers, some unexpected; was he doing Jay & the Americans’ “Come a Little Bit Closer” as a joke, or did he really like the song? Other unexpected choices include “Yesterday,” “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” Universal Soldier,” and “Da Doo Ron Ron.” Woman backup singers add some uncharacteristic touches, and Al Kooper plays some characteristically interesting keyboards, though he doesn’t have nearly as much to work with as he did on Dylan’s mid-‘60s sessions. I like how he mimics locust chirps on take 2 of “Day of the Locusts,” though, and the March 1970 take 6 of “Went to See the Gypsy” is fairly good (a different version from three months later was used on New Morning).