There was a slight slowdown in the kind of music documentaries I like to see in 2022, and not as many top-tier ones as there have been in some recent years. And there weren’t classic documentaries on the order of last year’s The Beatles: Get Back and Summer of Soul, or 2020’s Laurel Canyon. That’s how it goes sometimes. You can’t have high points like these every year.

Nonetheless, there were enough worth seeing to fill out a dozen or so reviews on my 2022 list, supplemented by reviews of a few 2021 releases I didn’t see until this year. As always, I didn’t get to every doc I might have liked, like the one on King Crimson, for instance. Some others I haven’t seen have only screened briefly at festivals so far, like the ones on 1970s L.A. session musicians, Judee Sill, Dionne Warwick (first screened at a 2021 festival, but not airing on CNN until January 2023), Roberta Flack (already screened at a festival, and not airing on PBS until January 2023), and Don Letts. If I see those in 2023 and like them, they’ll make it onto my 2023 best-of blogpost in my usual supplement of items worth noting from the previous year.

1. Travelin’ Band: Creedence Clearwater Revival at the Royal Albert Hall. In April 1970, CCR were filmed in concert in London’s Albert Hall. While the footage has unofficially circulated for a long time, this hour and a half documentary marks its first official release. To fill out the running time, though purposefully so, the first part is a condensed but useful rundown of how Creedence rose to superstardom, with excerpts from TV/concert performances and promo films, and some brief interview snippets from the era with band members. The majority of it simply presents the concert, filmed in a straightforward no-frills fashion. The image and sound quality are better than they are on the unauthorized copies, and the performance is solid and gutsy.

Creedence weren’t the most visually exciting act, and besides leader John Fogerty, they weren’t too animated onstage. Fogerty famously dominated their music, and he also dominates their concert presence, singing and shaking like an electric current is surging through his body. In retrospect the setlist could have benefited from some of their less frenetic classics like “Down on the Corner” and “Who’ll Stop the Rain.” But most of their big early hits are here, including “Proud Mary,” “Born on the Bayou,” “Green River,” “Fortunate Son,” “Travelin’ Band,” and “Bad Moon Rising.” So are some of their better relatively deep tracks, particularly “Commotion,” and decent covers of “Midnight Special,” “Night Time Is the Right Time,” and “Good Golly Miss Molly.” The set-closing “Keep on Chooglin’” choogles on too long, but that’s how it often goes for concert finales, and most of the set features far more concise numbers.

A good number of music documentaries these days try to be arty and act as much as a vehicle for a director’s personal expression as an actual document of the performer and the music. One such movie is detailed near the bottom of this list. That’s really not necessary most of the time (and is sometimes a significant drawback), and wouldn’t be at all appropriate for Creedence Clearwater Revival, one of the most straightahead no-nonsense great groups of all time. So you get a straightahead, no-nonsense document here, and that’s how it should be, even if their interview comments are on the brief, ordinary, and sometimes even mundane side. I had not seen the promo film of “Looking Out My Back Door” that plays alongside some of the credits, so make sure you stick around for those.

2. The Lost Weekend: A Love Story. “The Lost Weekend” is the name often given to the year and half or so from around mid-1973 to early 1975 when John Lennon and Yoko Ono were separated. The love story this documentary addresses was between Lennon and May Pang, an assistant to John and Yoko who became Lennon’s girlfriend during this period. She narrates this 95-minute film, which tells the story of her and John’s affair from her perspective. While her voiceover can be sentimental and melodramatic, it’s reinforced by a wealth of period film clips, photos, and interviews, some pretty rare. There are excerpts from TV interviews Lennon gave at the time, and Pang’s given since; home and amateur movies from the era; and interviews from associates like publicist Tony King, Alice Cooper, and session drummer Jim Keltner, though John’s son Julian is the only one featured in recent on-camera interviews (besides Pang herself in a brief reunion with Julian near the end). There’s not much Lennon music, but there are a good number of his drawings, some specifically (and graphically) about his relationship with Pang. Some animated sequences fill in some gaps where not much or any period films/photos/graphics are available.

Of course with John Lennon being long gone and Ono only represented by a few film clips, this might not be the fullest record of a pretty complicated situation. It does let Pang voice her take on it and memories at length, emphasizing that in her view Lennon had a lot of love for her and was often happy during this time. Yoko comes off as a fairly manipulative figure, helping to arrange the affair until she wanted to resume her life with John, and then setting up a scenario where Lennon visited her and never came back. It’s noted that communication and even intimate relations between Lennon and Pang didn’t entirely stop after he returned to Ono, though the post-1975 years don’t get much coverage. There are also some recollections and comments on Lennon’s sporadic visits with Paul McCartney in the mid-1970s, who delivered a message from Yoko to John asking him to return, though that wasn’t acted upon for some time. Considering she worked for Allen Klein’s company before becoming a personal assistant to Lennon and Ono, there aren’t comments on Klein and how he affected relations between the Beatles, though the termination of his position with the Beatles at the end of 1974 is noted with photos. But you can’t have everything, if Pang indeed had any insight into that complicated situation.

3. Neil Young, Harvest Time (Neil Young Archives). It’s hard to know whether to even list this as a standalone film, since it’s part of—and just one DVD disc—in a five-disc box of the 50th anniversary edition of Young’s Harvest album. In keeping with the kind of eccentric catalog marketing we expect from him, although a website dedicated to the film indicated that screening times would be displayed starting December 1, none have. It has screened a few times in at least one theater in Marin County, however, and that’s enough to count it as a documentary you (hopefully) won’t have to buy the whole box to see.

Harvest Time is a two-hour documentary, or perhaps more precisely, a compilation of footage taken during the making of Harvest. This includes recording sessions at his barn in Northern California and Nashville with the Stray Gators; vocal overdubs in New York with Stephen Stills and David Crosby (for “Alabama”) and Stills and Graham Nash (for “Words”); the two tracks Young recorded, on piano and vocals, with the London Symphony Orchestra in London; and miscellaneous scenes of Young and others being briefly interviewed, fooling around and relaxing on his ranch and in studios, and Neil being interviewed at a Nashville radio station. Basic subtitles tell you who’s who, though since it does jump from place to place in non-chronological sequence, it would have helped to have some other basic subtitles explaining how the clips fit into the album’s evolution.

Since the pace is erratic and at times drags, this is primarily for serious Young fans. There are a lot of those, however, and the better parts, which comprise the majority of the film, are certainly interesting, for close looks at the Harvest material as both works-in-progress and nearly-final versions. Some of the repetitious jamming on basic riffs and chord progressions at the barn goes on way too long (especially in the instrumental part of “Words”). But the more concise performances are very good and very live, including Young playing with the symphony, which is done in the same room as the orchestra, not as overdubs. It’s pleasing to see Young getting along well with the rest of CSNY on their vocal sessions, and there are appearances, if cameo-like, from a number of important associates, like producer Elliot Mazer, keyboardist and sometime arranger Jack Nitzsche, and Louis Avila, the ranch caretaker who inspired “Old Man.”

While the interview bits can be mumbly and unrevealing, a few interesting comments pop up. Young says “Alabama” wasn’t so much about the state Alabama as things he was feeling, and when London Symphony Orchestra conductor David Meecham asks him if he knows about Pink Floyd, he seems unfamiliar with the group—not as surprising, maybe, as you might think, since they had yet to become US superstars with Dark Side of the Moon. The young boy (who looks about ten) who does an impromptu off-the-air interview with him at the radio station actually asks reasonable questions for someone his age, and Young tells him his favorite artist, at least at the moment, is Merle Haggard. The kid had interviewed Ringo Starr when he was in Nashville to do Beaucoup of Blues, and says Ringo told him he didn’t enjoy making Let It Be. Young comments, fairly reasonably, that it could have been because that record was done in pieces (albeit most of it was done in January 1969), and that Buffalo Springfield’s last album was also done that way.

Some of the musical highlights are performances that didn’t figure or are unlike those on the final album, like a solo piano version of “Journey Through the Past”; a solo banjo version of “Out on the Weekend”; and an unplugged guitar-harmonica version of “Heart of Gold.” If you want more from this era, the box has Young’s just-over-half-hour BBC TV concert from February 23, 1971 on both DVD and CD.

4. Johnny Hallyday: Beyond Rock (Netflix). Hallyday was about the closest equivalent France had to Elvis Presley, though it’s doubtful his rabid French fans (and there were many) would quite claim he was Elvis’s equal. This five-part, nearly three-hour documentary series covers his long and volatile career with fervor, with many, many archival Hallyday performance and interview clips. There are also archival clips of his wives and lovers (including his first wife Sylvie Vartan, herself a big French singing star), and several associates, biographers, and general media figures are heard in voiceover comments. The pace is so fast it verges on hectic, covering his life from his beginnings as a teenage hitmaker heavily influenced by American rock’n’roll, through his next half century or so as an up-and-down superstar and occasional actor.

Although there are a good number of clips of Hallyday in musical performance from the early 1960s through the early twenty-first century, nerd collectors from the English-speaking world should be cautioned that it’s not too heavy on analysis of his records and musical progression, such as it was. If you want stories about the Jimi Hendrix Experience opening for him on some of their first shows in late 1966, or the Small Faces backing him on some late-‘60s recordings, or his attempts to break into foreign markets by recording in Nashville and appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show—or even his fine starring role in the 2002 film The Man on the Train, which might be the artistic feat for which he’s most known to English-speaking audiences—be warned that there are none. There is, however, a lot about his stormy marriages and romances, which besides Vartan included noted singer Nanette Workman and star French actress Nathalie Baye (herself more known to British and North American audiences than Hallyday), as well as the teenage daughter of one of his best friends, who became his third wife. There’s also a lot about his generally reckless celebrity behavior, including car crashes, alcoholism, and an attempted suicide.

Plus there’s plenty of time given to his over-the-top, massively expensive in-concert spectacles, which got ever more gargantuan in his later years. Even if Hallyday’s music is not to your taste, these have their share of sheer weirdness, as when Paul Anka keeps trying to get a sort of MIA Johnny to come out and start a major Las Vegas concert in the mid-1990s. Hallyday helped fly over many French fans for these shows, which were considered a major disappointment. These were committed admirers of the singer whose general appraisal of the man’s talents were unlikely to be dampened, but non-French viewers will likely still be mystified by his massive French superstardom, culminating in a large state funeral after his 2017 death. As unlikely as this series will be to make new converts outside of his homeland, it has its share of entertainment and social history value, if bloated a bit by the frequent focus on his personal foibles and family issues.

5. Buffy Sainte-Marie: Carry It On. This hour-and-a-half documentary in the American Masters series follows a common format for that PBS program: interviews (many recently done with Sainte-Marie), numerous brief archival performance and interview clips (many of the music ones are exceptionally brief), and plenty of historical photos. The format might be typical, and with a career as long and multi-dimensional as hers, there’s no way to cover everything, or cover much of what it does touch upon, in depth. What is presented is worthwhile, however, particularly Sainte-Marie’s own extensive memories and perspectives, even if some of them have been covered quite a bit in other interviews. Associates interviewed include Taj Mahal, Steppenwolf’s John Kay, Robbie Robertson, and in a testament to how highly regarded she is by some other musicians who sold a lot more records, Joni Mitchell (interviewed while the film was in production, and after her very serious illnesses of recent years).

While her music is naturally detailed from her early-‘60s folk revival roots to a November 2021 concert shortly after the famed venue (Toronto’s Massey Hall) reopened, so is her acting (including her long-running part-time cast membership in Sesame Street), activism on behalf of Native Americans, and her views on how she feels her music was actively suppressed by the government in the 1960s and 1970s. Her sometimes rough experiences in the music business, and particularly Vanguard Records, are noted. So are, to an unusual degree even for a public television special, the sexual molestation she suffered as a child and the abuse she endured in her marriage to her second husband, musician/arranger/songwriter Jack Nitzsche. Although there’s much praise heaped upon Sainte-Marie’s music and character, an unexpected note is sounded by Joni Mitchell (who generally is very complimentary about Buffy) in how Mitchell changed her opinion about “Universal Soldier,” feeling it was inappropriate for the effect it might have on soldiers returning from Vietnam.

Sainte-Marie says that Mitchell didn’t sign to Vanguard because of how they’d treated her, and Mitchell remembers not going with Vanguard because of unreasonable terms, specifically requiring multiple albums per year. It’s a footnote of sorts within this documentary, but it would be interesting to get Vanguard’s point of view on this, whether their perspective would be different or not. Maynard Solomon, the key executive at Vanguard, died in 2020, and of course might not have been available or willing to participate in a project like this. I did get to speak to him briefly when I was researching my books on 1960s folk-rock about twenty years ago, and I don’t know whether the label’s relationship with Sainte-Marie would have come up had I interviewed him, but in any case he declined to be interviewed.

6. Bonnie Blue: James Cotton’s Life in the Blues. Cotton had a long career as one of the best blues harmonica players, and was also a serviceable singer and songwriter, though his instrumental virtuosity was by far his biggest distinction. This documentary is kind of sketchy as far as presenting a thorough biography, though it hits on key points like his first recordings for Sun Records in the 1950s; his work as a vital sideman to Muddy Waters; his crossover to white rock audiences starting in the late 1960s; and his struggles with throat cancer late in life, which didn’t keep him from continuing to play harmonica and record. Cotton was interviewed for the film not long before his 2017 death, though these segments aren’t too numerous, and subtitles are used as his voice had been ravaged by disease. There are many comments by some who knew or worked with him, and of course some crucial associates from his prime, like Waters, are gone (in some cases very long gone). So much of the interview material was done with musicians who worked or were influenced by him in his final decades, some with rather tenuous connections to the man. Also interviewed were two of his managers (one of whom was also his wife in his final decade), along with a girlfriend from the ‘70s.

Much is left uncovered in this film, like his records for Verve and Vanguard in the late 1960s, arguably his best (and for that matter most of his other records). A previous wife is mentioned, with few additional details. But there’s some good stuff, like his memory of how he came up with the harmonica riffs for Waters’s classic “Got My Mojo Working,” which he feels sold the song. There are also archive clips, if usually on the brief side, of Cotton in performance going back to his appearance in Muddy’s band at the Newport 1960 Folk Festival. Some color footage of Cotton at his most animated, looking to be from the late ‘60s, is good enough that you wish there was more, perhaps as DVD/Blu-ray extras in the future. His spot on Playboy After Dark in the late ‘60s, with Luther Tucker on guitar, is conspicuously missing, maybe for licensing reasons.

One minor part of the film that caught my attention, though it’s not too crucial to the whole: Al Dotoli, who managed Cotton in the 1970s, discusses freeing James from a management deal with Albert Grossman. Dotoli says that Grossman sent Cotton out for low-priced gigs to fill out bills when bigger stars weren’t available, and feels Grossman was destroying the bluesman’s career by undervaluing him. He remembers freeing Cotton from Grossman’s management after telling Grossman that he’d be getting a lawyer involved. Subsequently, Dotoli relates, Cotton’s fees went way up for concerts. Grossman did not have a reputation of being easily cowed, and I wonder if there is more to this story, though I don’t think it will be told if so, especially with Grossman also long gone.

7. Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues. There’s a lot of material sourced for this documentary, including archival clips stretching from the early 1930s to shortly before Armstrong’s death in the early 1970s; interviews, some with Armstrong, some on camera but most heard as audio-only over images, with several dozen musicians and critics; and interview tapes the jazz legend made discussing his life in his later years. While it covers a lot of territory, it’s kind of rambling, jumping between eras and subjects, if in a somewhat chronological order more often than not. There are many other places you can learn about Armstrong in a more thorough manner that’s sequenced in an order where it’s easier to follow what happened when. However, there aren’t many other, if any other, places you can see and hear so much of and about him at once, much of it rare. For that reason it’s worth viewing, though it might be more something to stoke your curiosity about learning more than a definitive summarization up of what’s most important about Armstrong.

Within a format that’s not my first choice for structuring documentaries, this includes quite a few clips from his numerous appearances in films; discussion of his civil rights activism, though this was muted in comparison to some of his contemporaries, particularly younger ones; and his overseas trips that helped spread jazz and US culture abroad. His music isn’t ignored, some of the points made including how he helped define the range employed by jazz with his use of high notes, and how his style of scat singing was, like his trumpet playing, innovative and influential. One of the most amusing references is to a quote by James Baldwin, who after hearing Armstrong’s version of “The Star Spangled Banner” remarked that it was the first time he’d liked that song. Reviews of this film have sometimes emphasized how the previously unheard interview tapes have a lot of racy language, but although that would have been scandalous had it been widely heard at the time, it’s now not too much out of the ordinary for how many celebrities have been caught talking on record.

8. Jimmy Savile: A British Horror Story. This is tangentially related to rock music history, and even that tangent might be little known or unknown to many outside of the UK. In the UK, however, Savile was hugely famous as a radio disc jockey and host of Top of the Pops. He was also highly visible in other TV programs and media, and as a fundraiser for charities and general hobnobber with celebrities, getting knighted in 1990. In the US, his connection to rock is mostly known via his role as compere in mid-‘60s NME Pollwinners Concert clips that have gained wide circulation. Globally, he’s now hugely infamous as having been revealed as a sex predator in hundreds of cases that came to light soon after his 2011 death.

This two-part, three-hour documentary doesn’t cover his life in a linear fashion, and non-UK viewers might come away with gaps as to his rise to fame and his chief activities. Instead, it emphasizes his ghastly private life, and the trail that led to the posthumous revelation of his nefarious deeds, as well as his successful burial of those from legal and public eyes while he was around. As the subtitle announces, it’s a horrific story, combining lots of vintage footage with interviews with many of his associates and investigators. Grim it is, not only if principally for documenting his sex crimes. Those aside, he was a pretty creepy fellow with no apparent inner life, and, at least to this viewer, not very funny, though it was as a comedian of sorts that he gained renown. Many of his jokes about what he did in his free time, glossed over as not-so-naughty bits when they were uttered in very public forums, are strikingly sexist. With hindsight, they’re also very strong hints as to what he was really up to on his own time, which makes the public’s acceptance of his behavior galling, as well as the actual behavior itself.

9. If These Walls Could Sing. The history of Abbey Road Studios, formerly EMI Studios, is enormously extensive even if you don’t count what the Beatles recorded there. It’s too much to cover too comprehensively in a ninety-minute documentary, which does include a lot of Beatles, though not as much as you can find out in many other sources. The subject warrants a multi-part series, but leaving aside the incompleteness and just going on what is covered, this has some interesting material. This includes first-hand interviews with Ringo Starr, Roger Waters, David Gilmour, Cliff Richard, Elton John, the Gallaghers from Oasis, and naturally Paul McCartney, whose daughter Mary directed this Disney-streaming feature. There are also some interesting archive clips, not just of the lives of the above-named artists, but also less obvious names like Cilla Black and classical cellist Jacqueline du Pre. There are a few uncommon stories and unexpected inclusions, like Jimmy Page and Shirley Bassey remembering recording the theme to Goldfinger, where Bassey collapsed after hitting the final operatic sustained note, and Fela, who’s discussed (not interviewed, obviously) in relation to his ‘70s recordings there.

Fans of all sorts of mainstream and specialized tastes, of course, can list a bunch of interesting artists and projects that aren’t covered. Just in the Beatles era, there’s the Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle and the Pretty Things’ S.F. Sorrow, which might not be as iconic as Sgt. Pepper, but also expanded the boundaries of what was possible in a rock studio recording. The Hollies are only covered in relation to Elton John’s piano part on “He’s Not Heavy, He’s My Brother,” and Merseybeaters Gerry & the Pacemakers and Billy J. Kramer pretty much skipped (not to mention George Martin-produced mod band the Action, if you want to get cultish). Speaking of Martin, what about the Goons and Peter Sellers comedy records he made before the Beatles? Or even the early Beatles solo records by George Harrison and John Lennon where sessions were held at Abbey Road?

The list could go on, though for what’s covered, the value lies not so much in novel information as hearing the stories told in the words of the participants. Starr has a funny comment about how McCartney would nag the Beatles to record: “If hadn’t had been for him, we’d have made like three albums instead of eight.” Actually the Beatles made more than eight albums (eleven full ones in the UK plus some non-album EPs and singles), but the point’s clear enough. The last sections dragged as I’m not interested in John Williams’s Star Wars soundtracks or the more recent artists, but appreciation of those parts will vary according to viewers’ tastes, not the competent direction.

Spoilsport alert: a clip of Pink Floyd from early 1967 identified as having taken place in Abbey Road’s Studio Three was actually filmed in Sound Techniques, as verified by numerous Pink Floyd/Syd Barrett books. Quality control slipped on that one. More seriously, the section with Kanye West, though brief, is the kind of inclusion not welcome here or anywhere else.

10. The Sound of 007 (Prime Video). There have been no other film series besides James Bond’s where the music is so well known or important. Of course, there have been few if any popular series of this length, accounting in part for the familiarity of many of the theme songs (and some motifs in the soundtracks) even to viewers who haven’t seen many of them, or aren’t particular fans of the franchise. This documentary covers a lot of the music used from the first Bond films in the early 1960s to the present, with first-hand and vintage interviewers with many of the performers, composers, record producers, and film producers. There are also many clips from the movies and some of performances of the songs, which are necessarily brief to keep within the ninety minutes.

No one’s taste is going to be so broad that they’ll like all (or perhaps even the majority) of the Bond music, as the styles stretch over more than half a century. But it’s likely almost everyone likes at least something, even if you haven’t kept up with the series for many years, as I haven’t. Performers represented, and sometimes interviewed, include Paul McCartney, Shirley Bassey (of both “Goldfinger” and “Diamonds Are Forever” fame), Tom Jones (“Thunderball”), Nancy Sinatra (“You Only Live Twice”), Jack White, Billie Eilish, Tina Turner, Duran Duran, and naturally John Barry, the most important by far of the composers who’ve worked on the instrumental part of the soundtracks. The origination of the super-familiar principal instrumental theme is discussed in some depth, and the point is rightly conveyed that Barry managed to combine big band and orchestral music, as well as parts of jazz, pop, and rock. Structurally this jumps back and forth between eras and themes pretty quickly, and a more chronological approach would have pleased me, if not necessarily the majority of viewers. There’s still something of interest for almost everyone here, though it’s likely few if any will be interested in all of the music discussed.

11. Moonage Daydream. Perhaps the most discussed and to some degree acclaimed music documentary of the year, this somewhat avant-garde look at David Bowie got its share of good-to-rave reviews in the music and mainstream press, including five-star ratings by the Guardian and Record Collector. Every social media post I saw about it in the week after its release was similarly complimentary. I was wary, however, after a filmmaker, musician, and general fanatical rock/Bowie fan whose opinion I respect saw it in IMAX days after its release and expressed major, even severe disappointment. He went as far as dubbing it an infomercial for Bowie’s catalog. For good measure, he added that all the Bowie fans he knew—and he knows more than one or two—agreed with his assessment. So do I, even if I’m not quite as down on the movie as he is. If nothing else, it’s good to know I’m not alone, even if he and I might be in the minority.

It’s hard to know where to start in even describing, let alone judging, this strange take on Bowie’s legacy and accomplishments. It’s not laid out in linear chronological fashion, and doesn’t have interview material with anyone but Bowie, represented both by visual and voiceover archive interview clips. I can handle this, though it’s not my favorite form of documentary. However, it seemed like a good third or so of the movie was loud and garish hoo-hah, including lots of sequences featuring special effects graphics and historical images/photos that were not specifically (or often even generally) related to Bowie. Such images/photos were used a lot in Todd Haynes’s Velvet Underground documentary, which I also thought unnecessary in their abundance. But there’s a lot more such material in Moonage Daydream.

More importantly, even if I thought the VU documentary was imperfect, generally it was pretty worthwhile. I can’t strongly recommend Moonage Daydream, even after (yes) seeing it in IMAX. There are plenty of snippets, if usually brief, of Bowie in performance, some rare, some pretty common. There is, however (and it seems deliberately), little context, or sense of how exactly he evolved through his various unpredictable phases, other than some reflections on his move toward the superstar mainstream in the 1980s. There’s also an inordinately large amount of screen time given to seeing Bowie on escalators or walking around exotic locations, although at least he’s present, unlike in the march of images without Bowie associations.

One uncredited voiceover (not Bowie’s), presumably from a critic or media figure, credits him with running before he even walked considering his accomplishments in several media, including music, film, and (with the Elephant Man) theater. It’s true he explored all those mediums, but he did have to walk before he ran, struggling for five years with several record labels and non-hit records before his 1969 “Space Odyssey” hit. Then there were three more years before his next hit, which included some of his best (though not most commercially successful) music. This isn’t addressed at all, other than with the inclusion of some very brief images from the period. Nor is his short but significant shift toward blue-eyed soul music in the mid-1970s.

Many (especially young viewers) not too familiar with Bowie will likely find the movie’s arc hard or impossible to follow (and in his Record Collector interview, director Brett Morgen contended there was an arc and narrative). Big Bowie fans won’t find much here, at least in the way of hard musical content and perspectives from the singer himself, with which they’re not already familiar. So I’m not sure who’ll get a lot out of watching it—other than, admittedly, the numerous reviewers and fans who are praising or raving about the film.

Although some of the press for the film emphasized the director’s access to rare and previously uncirculating material from Bowie’s archive, there’s relatively little such footage to see (or voice to hear) for fans to chew on. Some of the footage most heavily drawn upon is pretty common, like sequences from D.A. Pennebaker’s Ziggy Stardust documentary of a 1973 concert, or scenes from his best known (and best) film as an actor, The Man Who Fell to Earth. Key associates like Mick Ronson are seen but not mentioned. Some key associates, like his first wife Angie, aren’t mentioned or, as far as I could tell, seen; it’s hard to say with the near nonstop assault of images, many brief. These include glimpses of a script for a Diamond Dogs film and a 1974 diary (I think that’s the year; it flew by onscreen fast) that would be interesting to read, though you only see fleeting glimpses that will be impossible to decode unless you can read freeze frames on home video.

So what’s this doing on my year-end list? There is some material that’s uncommon, like Jeff Beck’s guest spot on lead guitar when Bowie does “Love Me Do” and “The Jean Genie” in the 1973 “retirement” concert Pennebaker filmed, which didn’t make it into the Ziggy Stardust documentary. I’m not sure where the performance of “Rock and Roll with Me” was filmed—I think it might be an outtake from the mid-‘70s Cracked Actor TV documentary (excerpted a bit in various places in Moonage Daydream)—but I hadn’t seen it before. I’ve seen a lot, but not all, Bowie interview clips; some here were unfamiliar and fairly interesting.

There’s also some soundcheck and concert footage from 1978 London performances that Record Collector hailed as “the holiest of holy grails,” though it’s not my main Bowie era. Asked by the magazine whether the whole gig exists on film or Moonage Daydream includes everything from that source, director Morgen retorted, “Do you have another question?” It’s the kind of answer you might associate with someone like Lou Reed (himself seen only very briefly, despite his substantial influence upon and interaction with Bowie), and not an appropriate one for someone charged with accessing Bowie’s archive for what might be the only such extensive opportunity.

This was a long review, and for the short version, I’ll use a two-word quote from The Man Who Fell to Earth. Bowie’s character asks his former chief scientist (played by Rip Torn) if the scientist liked the album he’s made, The Visitor. Torn’s character replies tersely, “Not much.” An opinion to which the director of Moonage Daydream might respond by quoting Bowie’s character’s response: “Oh. Well, I didn’t make it for you anyway.”

12. Spector (Showtime). This three-and-a-half-hour, four-part docuseries isn’t quite a music history film. More than half of it’s specifically devoted to Spector’s trials for the murder of Lana Clarkson, though his musical career takes up the majority of the first episode, and some of the second. His trials, which resulted in a long prison sentence in which he died in jail, should not be ignored in an overview of his life, and nor should his frequent harmful and abusive behavior. Music was a big part of his life, however, and could have gotten more attention than it does here. What’s covered of that part of his history is pretty interesting, including good interviews with a number of close associates, among them Carol Connor of the Teddy Bears; fellow Brill Building songwriter-producer Jeff Barry; Darlene Love; La La Brooks of the Crystals (who gives a notably different account of the production of “Da Doo Ron Ron” than Love does); Nedra Talley of the Ronettes; session musicians Don Randi and Carol Kaye; biographer Mick Brown, who did the last interview with Spector before Clarkson’s death; and, if only briefly from archive footage, Ronnie Spector and Tina Turner. Phil Spector is represented by some archive footage, some interview clips from the early 2000s from Vikram Jayanti’s documentary The Agony and the Ecstasy of Phil Spector (Jayanti is also interviewed), and scenes of Spector in the courtroom.

This is more of a true crime documentary than a music one, and that side of the story is covered exhaustively, and not just with courtroom footage and period news clips. There are also interviews with prosecution and defense attorneys, Spector’s driver the night of the murder, a juror, Spector’s daughter Nicole, Clarkson’s mother, and friends and associates of Clarkson, who’s seen in much footage taken from her work as an actress and comedian. If you’re as sensitive to chronological accuracy as I am, it’s unfortunate the sequencing can give the impression that Spector produced John Lennon’s Rock’n’Roll album before his marriage to Ronnie Spector nearly a decade earlier, though there aren’t other missteps on that order. The Agony and the Ecstasy of Phil Spector, from 2009, has not been available on home video or through streaming as far as I know, but has some other interesting information and perspectives about Spector’s work and criminal activity.

13. Just a Mortal Man: The Jerry Lawson Story. Jerry Lawson was lead singer in the Persuasions, the (usually) a cappella harmony group with a strong soul bent. This documentary aired on PBS, and Persuasions fans should be aware that it’s a film about Lawson, not specifically about the Persuasions, though they strongly figure in the coverage. The approach is conventional, with numerous brief bits of archival performance footage as far back as 1968 spicing memories from Lawson (who died when the project was in post-production), family, associates (the closest of which is manager/producer David Dashev), and later vocal groups who claim the Persuasions as an influence. There are plenty of sincere testimonies to his talent and character that, again in common with many music documentaries, could have done with some editing to avoid repetition of similar sentiments.

If you’re looking for in-depth examination of the Persuasions’ career, this comes up short. Frank Zappa’s involvement in helping launch their recording career is touched upon only briefly; the other Persuasions, aside from bass singer James Hayes, are barely mentioned; and their albums hardly discussed. There’s a lot about Lawson’s personal life, including his family background; his unfortunate fallout late in life with Hayes, the Persuasion to whom he was closest; his problems with alcohol, though he stayed sober the last twenty years of his life; his second marriage; and his post-Persuasions work helping the developmentally disabled in Arizona. While acknowledging that the intent of the filmmakers was probably not to cover all the bases of the Persuasions, the too-brief numerous performance snippets from the late 1960s and 1970s make one hope someone writes a biography of this unusual and creative group, as much of a niche project as that is.

The following movies came out in 2021, but I didn’t see them until 2022:

1. Ennio. Although this has a 2021 date, as far as I know this two-and-a-half-hour documentary on Ennio Morricone has barely shown in the US, where I saw it as an online stream as part of a festival. Morricone was incredibly prolific in his lengthy career, and maybe there are some committed fans who will be dissatisfied with what it doesn’t include, or the brief coverage of many of the soundtracks and recordings it does cover. I can’t imagine too many people being dissatisfied with this film, however, since it gets through an immense amount of ground. There are extensive interviews with Morricone himself, by the looks of them done not long before his 2020 death, in which his recollection is good and his stories interesting. There are also several dozen interviews with associates and composers, many of them not so well known to English-speaking audiences. But quite a few of them are, including Joan Baez, Clint Eastwood, and directors Sergio Leone, Bernardo Bertolucci, Roland Jaffe, and Quentin Tarantino.

There are also excerpts from dozens of the films he soundtracked, from the internationally famous to the obscure. There’s some attention paid to the ‘60s Italian pop records he worked on as arranger, and while most of those artists are unfamiliar to English-speaking listeners, he occasionally did work with American stars—not just Baez, but also Paul Anka and Chet Baker. There are also archive clips dating back to his boyhood of Morricone himself in performance (on trumpet or, later, conducting) and being interviewed, as well as of interviews about Morricone. It does drag a bit near the end as awards and tributes dominate the screen, and certainly the most interesting and bulkiest sections address the peak of his career in the 1960s and 1970s. But while two-and-a-half hours might sound like too much if you’re not a fanatic, the pace is pretty snappy, and the assembly of clips from so many sources impressive.

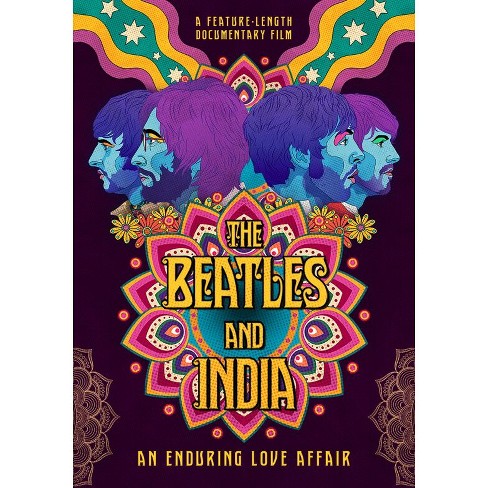

2. The Beatles in India (MVD). Indian music was a significant influence on the Beatles for a while, and so was the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi for almost a year, culminating in the Beatles’ visit to study transcendental meditation with him in Rishikesh. This documentary looks at how they (and particularly George Harrison) integrated the sitar and Indian music into some of their songs and records in the mid-1960s, and their visit to Rishikesh in early 1968, which ended with the group leaving without finishing their TM course. This ground has been covered by many other books and some films, but to its credit, this does have some material that will be unfamiliar even to big Beatles fans. In particular, there are film clips and interviews from their 1966 stopover on the way back from Manila; clips from Harrison’s visit to study sitar with Ravi Shankar later that year, including bits from a radio interview that wasn’t rediscovered for many years; and quite a bit from the 1968 Rishikesh jaunt.

There are also interviews with some Beatles associates, most valuably George’s first wife Pattie Boyd; some Indian journalists and photographers who interacted with the group; and some of the other people who were in Rishikesh when the Beatles were there, including the mother of the tiger hunter who inspired “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill.” True, a lot of people aren’t heard from, whether the surviving Beatles, Donovan (also at Rishikesh), Mike Love (also at Rishikesh), or Mia Farrow (also at Rishikesh). There’s also some extraneous Beatlemania footage and interviews that could have been excised to pare this down a bit. It’s still above average for the many peripheral Beatles documentaries made without a ton of resources.

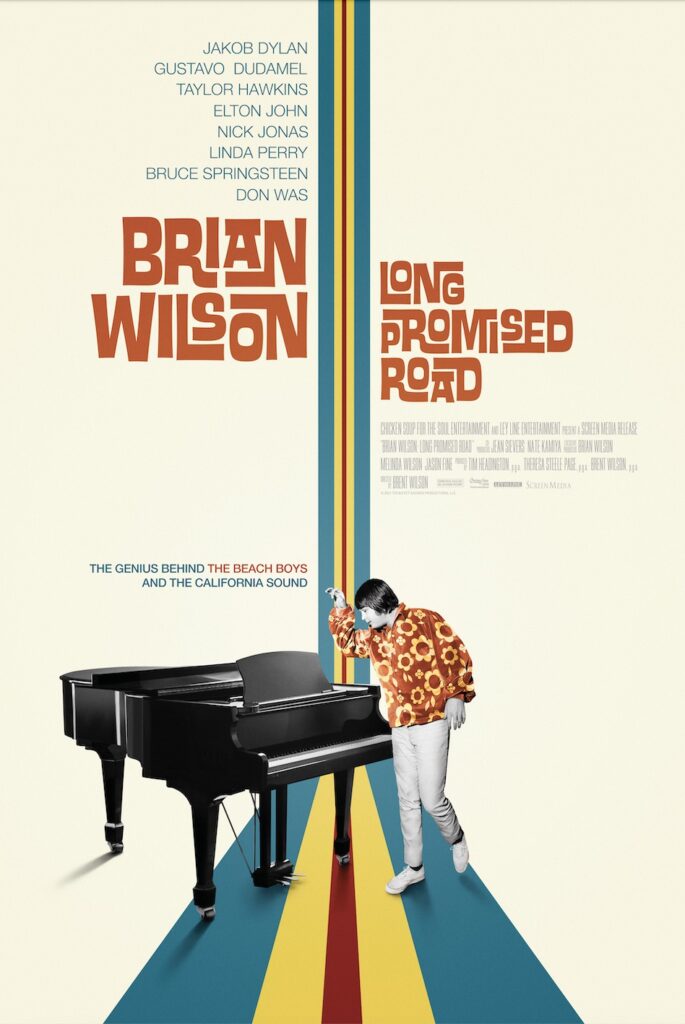

3. Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road (Texas Pet Sounds Productions). This follows a format that plenty of other rock and celebrity docs do, mixing some (not a ton) of vintage footage and interviews with plentiful testimonials from fellow musicians and recent footage of Wilson talking, recording, and performing. While some of the talking heads are from veteran stars (Elton John, Bruce Springsteen), others are from much younger artists of subsequent generations, making basic points about Brian’s life and work. Much of the content stems from conversations between Wilson and his music journalist friend Jason Fine as they drive around Los Angeles, sometimes revisiting his former homes and haunts. Wilson’s never seemed the most comfortable interview subject, and his memories and answers can be pretty terse here.

There are other documentaries that will tell you more about Wilson and the Beach Boys, and some big fans might be disappointed there’s not more substance in this one. So might some more casual fans, the film jumping back and forth chronologically without giving a linear history of his life and artistic evolution. Whatever your grounding, it’s best to treat this as a modest endeavor that doesn’t have excessive depth, but has interesting stories here and there. It does touch upon some sensitive subjects like his rough relationships with his father and psychiatrist Eugene Landy, and celebrates his ones with brothers Carl and Dennis, though Mike Love is barely mentioned (albeit Brian does praise his singing). There’s also some, though not much, old Beach Boys footage that isn’t often seen, like a 1964 interview in Oklahoma.

Note that the fifteen minutes of DVD extra are worth seeing if you’re interested enough to see the main documentary, since the outtakes are about on par with what’s in the principal feature, and don’t overlap in the subjects covered. If you want something to get angry about, a clip of the Beach Boys performing “I Get Around” is subtitled as being from 1963, though the song wasn’t recorded until 1964.

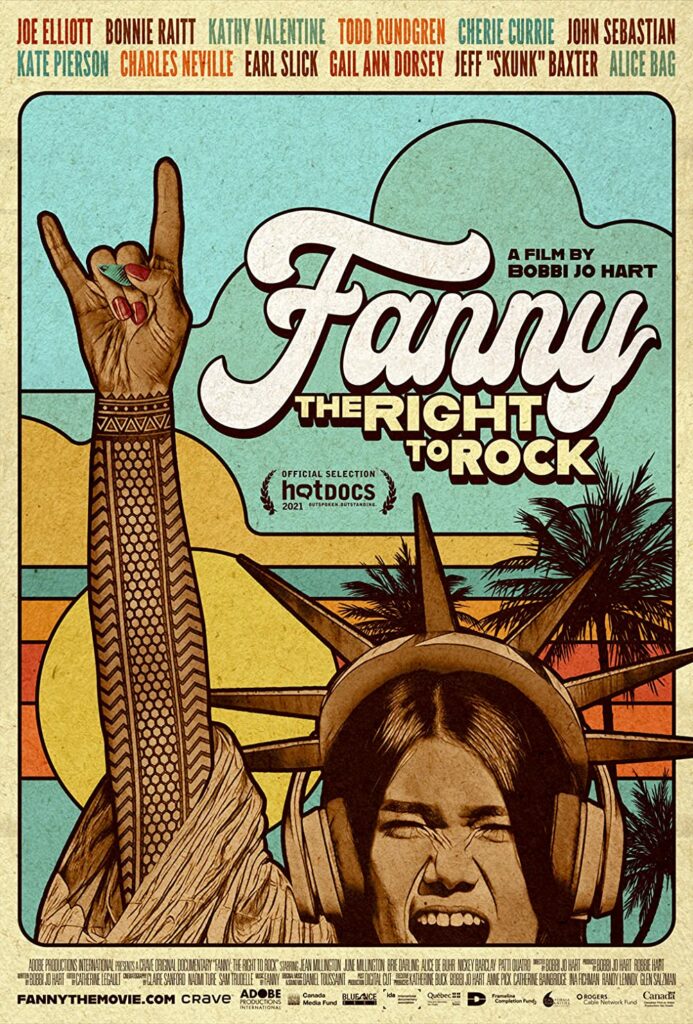

4. Fanny: The Right to Rock. Fanny were one of the first all-women rock bands who played their own instruments to make a mark, issuing a few albums on major labels in the early 1970s. I find their story more interesting than their music, which was hard rock with touches of glam, but the story’s told pretty well in this documentary. Most of Fanny’s members were interviewed (with keyboardist Nickey Barclay a notable exception), as were producers Richard Perry and Todd Rundgren, and a few admiring famed musicians like Bonnie Raitt, Kate Pierson of the B-52’s, and Kathy Valentine of the Go-Go’s. There’s not a ton of archival Fanny footage, but there’s some, as well as many vintage photos. Aside from the expected obstacles they ran into as a pioneering all-women band, the discrimination some members faced because of their Filipino background and/or gay sexuality is also discussed. So are the wild times at their Los Angeles group home in the early 1970s; the painful departure of original drummer Brie Howard, ascribed to getting pushed out at the behest of Perry; and how their Top Thirty single “Butter Boy” was inspired by (though not about) David Bowie, a fan of the group who had a brief relationship bassist Jean Millington.

Millington does speculate at one point that Fanny didn’t get bigger because they didn’t have great pop songs of the kind the Go-Go’s would. Personnel changes and lack of commercial headway led to their split in the mid-1970s, but Jean Millington, her sister and lead guitarist June Millington, and Howard reunited for a 2018 album. Much of the film focuses on this reunion and the recording sessions, though in a sad and unexpected turn of events, Jean Millington had a stroke that paralyzed her right side a week before the reunited lineup were to play their first show.

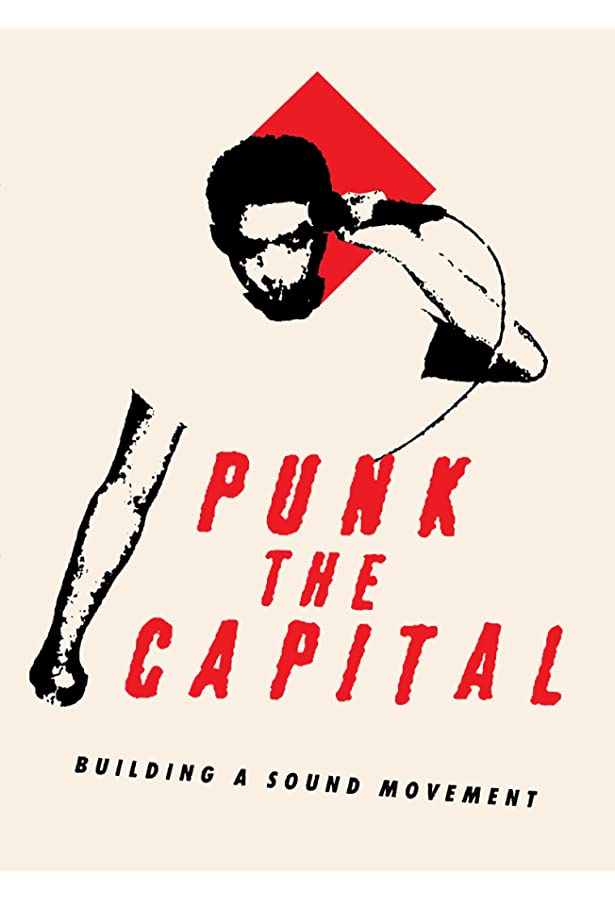

5. Punk the Capital: Building a Sound Movement (Passion River). From about the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, Washington, DC had one of the most active punk scenes, becoming particularly known for hardcore-oriented groups from the early 1980s like Minor Threat. This hour and a half documentary covers its history pretty well, with interviews from key figures like Minor Threat’s Ian MacKaye and Henry Rollins (who sang punk in DC before joining Black Flag), but also lots of other musicians, writers, recording studio personnel, and other scenemakers. Some of the bands interviewed and/or seen in archive footage are pretty obscure, at least if you’re not a punk collector, a la Enzymes, the Nurses, and Tru Fax and the Insaniacs. Others managed to make an impression outside DC and a good amount of records, like the Slickee Boys and Bad Brains. Be aware that much of the archive footage, with plenty of slam dancing and stage diving from the later years, is dark and blurry, though that’s kind of to be expected in much of what survives from the punk underground.

In some ways, the DC scene was typical of punk communities that made a mark: outsiders and misfits finding a home, wanting to do something different than the mainstream, doing things yourself when it seemed impossible through conventional channels, and the like. The key venues Madam’s Organ and the 9:30 club are part of the story, as is Dischord Records, who put out many records associated with DC punk, and were run by Minor Threat’s Ian MacKaye and Jeff Nelson. Like some other regional punk hotbeds, such as the ones in Southern California, DC punk was in danger of getting dangerous as the audience expanded and more thuggish violence occurred at shows. That’s discussed too, and it’s also noted that DC punk maintains a following as the scene was more heavily documented and archived than its usual counterparts.

The DVD has about fifty minutes of extras for the dedicated, including additional interviews with and footage of Scream, Void, and the Slickee Boys. 1960s garage rock completists should note that there’s an unexpected brief sequence with material about ‘60s DC garage band the Hangmen, since they were managed by the father of a couple guys in Scream.