As every year starts, it doesn’t seem possible there will be enough new music history documentaries up my alley to fill out a Top Ten list, let alone a Top Twenty one. Yet this year, as in most recent years, there have been more than enough. And there aren’t less documentaries are being made about more distant times – pre-1980s ones, say – as time goes on. If anything, there seem to be more, especially if you count some restorations, like I do.

I’ve generally gone with including films that did not seem to become known to more than a select few until 2024. As always, I’ve also put a supplementary list of documentaries of note that definitely were available in 2023, but which I didn’t see until 2024.

1. Stax: Soulsville USA (HBO). Justly and widely acclaimed, this four-part, approximately four-hour series covers the history of Stax Records well. Well enough, in fact, that there’s not to much to say about the format or criticize. It largely goes for the straightforward mix of first-hand interviews and archive footage, wisely letting the story be told by the music, the performances, and people who were there, though Stax historian Rob Bowman is one of the talking heads. The range of interviews used in the film is impressive, including some with key figures who are no longer alive. They range from star musicians like Booker T. Jones and Steve Cropper of Booker T. & the MG’s, Isaac Hayes, and Sam Moore of Sam & Dave to executive Al Bell, important songwriters like David Porter, and Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton, the brother and sister who founded Stax.

Also heard from are lesser knowns from the engineering, songwriting, session musician, and promotional departments who have interesting stories to tell. If the performance clips tend to be brief, some are rare enough to, as the cliché goes in these kind of reviews, make you hope some will be used in full as bonus features in an expanded release. Stax’s role in helping bringing people of different races together is properly hailed, but so are some of the tensions in severely segregated Memphis that sometimes made it hard to the label to operate, and sometimes fueled tension within the company.

Even with four hours, for those with a deep knowledge of Stax’s history, this will seem like something of a highlight survey. Some interesting performers, and certainly a good number of notable records, are barely noted or not mentioned. While CBS and the Memphis Union Planters Bank are targeted in some depth as the key factors that drove Stax out of business in the mid-‘70s just a few years after the label was still at the pinnacle of its success, it should be noted that some books and other writing on Stax cover other elements that helped lead to its demise. For all of these details, there are other sources to fill in the picture, particularly Bowman’s book Soulsville USA and Robert Gordon’s Respect Yourself, as well as the two-hour 2007 documentary Respect Yourself.

2. Let It Be (Disney+). The 1970 Beatles documentary (actually filmed in January 1969) Let It Be is renowned, even among many non-fanatics and non-collectors, for not having been available as a home video release for many years. In fact it was legitimately issued on VHS, if a long time ago, and it really hasn’t been too hard to see in non-authorized fashions in the decades it’s been officially unavailable. Still, its ready accessibility via streaming in 2024 is welcomed, and not just because it makes it easier to see, whether you’ve seen it many times and never seen it. This edition has been restored and looks significantly better than it did in its other iterations, including its 1970 theatrical release.

Unsurprisingly, some intense Beatles fans have voiced mixed feelings about the restoration, some feeling, for instance, that it’s not entirely faithful to how it was intended to originally look. The vast majority of viewers and fans, however, will probably find it considerably more enjoyable than it’s been in the past, even if you don’t care too much about restoration improvements. In part that’s because even the original release was grainy (partly a result of the original 16mm footage, intended for television, being blown up to 35mm for the theaters), and the sound imperfect, particularly the often mumbled or virtually inaudible spoken dialogue. Not everyone feels it’s proper to view such a sacrosanct item with subtitles, but they really do help you figure out many of the spoken exchanges, even if a good share of them are incidental or mundane.

As for the film itself, to repurpose the kind of cliché that sports broadcasters use when effusing over Shohei Ohtani, “What more can you say that hasn’t been said already?” It should be pointed out, however, that this is not a film that was made redundant by Peter Jackson’s justly hailed seven-hour Get Back docuseries a few years ago, which presented much more footage taken by director Michael Lindsay-Hogg than made the original Let It Be movie. There’s not much overlap between the two projects. Let It Be isn’t a day-by-day exposition of what the Beatles were doing this month; it’s more a survey of representative scenes from their rehearsals and recording sessions, capped by complete versions of future hit singles (“Let It Be” and “The Long and Winding Road”) in Apple’s studio, and then the legendary rooftop concert highlights.

It’s often been labeled as an inadvertent document of the Beatles’ breakup (although they would subsequently record Abbey Road and not break up with final certainty until April 1970), and some historical revisionism, including by Lindsay-Hogg and Jackson, has contended the group were actually having a lot of fun this month. Certainly they were, and certainly at the rooftop concert. But it would be inaccurate to argue some serious tensions weren’t caught on film, including uncertainty about what they were doing — a concert, a documentary, an album, or some/all/none of the above —and George Harrison temporarily quitting (discussed in depth in Get Back, but not at all in Let It Be). My take, not shared by everyone, is that it kind of captures the Beatles in an in-between mode — sometimes as good as ever, sometimes clearly floundering. There are certainly enough good/interesting moments — like their joyously ragged version of “Besame Mucho” and working out “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and (with just George and Ringo) “Octopus’s Garden” — to make the non-complete performance segments of the film worthwhile. There’s also the occasional hint at serious discord, like the famous brief sort-of-argument over how to play a guitar part between Paul McCartney and Harrison, or McCartney complaining about the group’s malaise to a pretty unresponsive John Lennon.

This would have contended for my #1 spot had this somehow only found its initial release this year, rather than having been around for many years and been seen by fans such as myself numerous times in inferior-looking versions. Note that there are some slight differences between the actual content of this version and previous ones. On the Disney Plus streaming, the film’s preceded by a brief (a little less than five minutes) discussion between Jackson and Lindsay-Hogg about the restoration. The end credits are different from the original ones, and are soundtracked by bits from the sessions that weren’t in the original film or released on record while the Beatles were active. The rooftop scene doesn’t stop with a freeze-frame of the Beatles as they finish their rooftop concert; they leave the scene in real time before the credits roll.

3. Revival69. While this is a documentary about the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival festival in September 1969, it should be clarified this is not a concert film, though there’s a fair amount of concert footage. Much footage from Little Richard and the Plastic Ono Band’s sets, and some from the sets by Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, and Jerry Lee Lewis, have come out on other home video releases. When I first saw a basic description of this 2024 release, I thought it might just repackage some or all of that. It’s an entirely different project, however, and a very interesting one. It’s a documentary about the festival itself, with as much or more attention paid to the seat-of-the-pants fashion in how it was organized as to the music at the event (which is also covered, not to worry).

While some of the participants are no longer alive, John Lennon being the most celebrated, an impressive number of others were interviewed, including promoter John Brower, musicians Robby Krieger, Alice Cooper, Klaus Voormann (bassist in the Plastic Ono Band), Alan White (drummer in the Plastic Ono Band), John and Yoko’s assistant Anthony Fawcett, concertgoers, the motorcycle gang head who put up some money for the festival, and even members of the film crew and Berry’s pickup band. The concert sequences are brief (if, in the case of Lewis and Berry especially, highly impressive), but effectively complement the storytelling, which uses some other footage taken around or related to the festival. There are even tapes of phone calls by the organizers as they tried to pull off the festival, and especially stunning is the use of tapes of phone calls actually made at the Beatles’ Apple organization.

Going by the accounts in the film, the festival, and Lennon’s appearance, hung by more of a thread than even the usual histories of the event have detailed. Had they not caught John and Yoko at Apple while journalist Ritchie Yorke happened to be there to vouch for their legitimacy, Lennon might not have gone; even as the rest of the band gathered at the airport to fly over, John and Yoko were begging off, a report that Eric Clapton (in the Plastic Ono Band for this appearance) was already at the airport apparently the key motivator in getting Lennon energized to make the flight. Had the organizers not been able to publicize Lennon’s appearance, the concert – also featuring the Doors and Gene Vincent — might have been canceled. Instead we had a key event in Lennon’s career, marking his first official concert outside of the Beatles, that was documented on film.

Lennon’s participation understandably gets a good deal of attention in this documentary, but the other acts on the bill are not neglected, even if, sadly, there’s no Doors footage; Krieger speculates Jim Morrison might have prevented them being filmed. It does make one wonder if more uncirculating concert footage might be available, and if it could be released at some point. As it is, this is a well-paced documentary that packs a lot of info and entertainment into its 80 minutes or so.

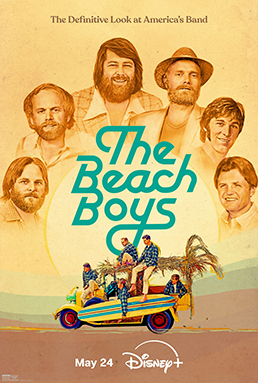

4. The Beach Boys (Disney+). There have been two previous documentaries on the Beach Boys, 1985’s The Beach Boys: An American Band and 2000’s Endless Harmony. This new, nearly two-hour one covers much of the same territory, as you’d expect, and doesn’t have factual discoveries that will surprise knowledgeable fans of the group. For those who are learning about the band, and for most who will be familiar with the story, it’s still pretty good, and more honest and forthright in its perspectives than the previous docs. Many of these are first-hand, benefiting from recent interviews with Mike Love, Al Jardine, and Bruce Johnston (though few from Brian Wilson), as well as archive interviews with Brian Wilson, Carl Wilson, and Dennis Wilson. Crucially, some other band members who weren’t with them for so long and are barely or not acknowledged in other histories are also heard from, those being early guitarist David Marks and early-‘70s addition Blondie Chaplin. Some key insiders are also interviewed either for the doc or in archive footage, including Brian’s first wife Marilyn Rovell, Wrecking Crew musicians Carol Kaye, Don Randi, and Hal Blaine, and lyricists Tony Asher and Van Dyke Parks.

There’s also quite a bit of performance footage, even if they’re pretty brief excerpts of songs, and some home movies, silent performance footage, and (again brief) 1960s studio footage, some of which is rare and perhaps not previously seen, at least by me. Most of the focus is properly on their first and best half dozen years, though some of the post-Smile era through their mid-‘70s comeback on the tails of Endless Summer is discussed. There’s too much commentary from a few artists and, particularly, one critic (Josh Kun) who didn’t play roles in the Beach Boys’ career. But fortunately, there’s not a great deal of such material, with most of the interviews reserved for the Beach Boys and associates.

As for the controversies and relatively dark sides of the story that are barely or untouched in previous documentaries (and some books), these include Dennis Wilson’s friendship with Charles Manson (with whom one meeting was enough for Love); Brian’s withdrawal from the group after they failed to complete Smile; and, most notably, the abusive behavior of the Wilson brothers’ father Murry, as well as his sale of their publishing for far less than it would ultimately be worth. Even this gets a fair hearing from different sides, Rovell opining a couple times that the Beach Boys would have never gotten to where they were without their father’s early efforts on their behalf. Some other relatively behind-the-scenes developments aren’t covered, like Carl’s protracted struggle to be granted conscientious objector status; the placement of Chuck Berry’s name on songwriting credits to “Surfin’ USA,” owing to that hit’s liberal borrowing from Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen”; and the strange management stint of the mysterious Jack Rieley in the early 1970s. This still gets most of the story down with a wider lens than the previous major documentaries, although their story’s interesting and involved enough to merit, if not the length of the Beatles’ Anthology, at least double the length of this feature.

5. Catching Fire: The Story of Anita Pallenberg. Pallenberg, as many Rolling Stones fans know, was about as influential on their figureheads’ lives as anyone who wasn’t in the group was in the 1960s and 1970s. She was Brian Jones’s girlfriend in the mid-1960s (and the most serious of his many girlfriends), then Keith Richards’s common-law wife from 1967 to the end of the 1970s (and mother of his first children), and also a co-star with Mick Jagger in the film Performance. This is a good documentary on a woman who, while figuring strongly in numerous biographies of the group, still retained some mystery as to her origins and professional/personal activities. Much though not all of this is filled in here with rare film clips of her (though mostly silent) from the mid-1960s onward, as well as interviews with the son and daughter she had with Richards and some interesting associates who aren’t usually heard from, like Volker Schlondorff (director of the 1967 movie in which she starred, A Degree of Murder); Sandy Lieberson, a producer of Performance; and Stash Klossowski, the aristocratic close friend of Brian Jones. Richards and Marianne Faithfull are represented by voiceover clips, and Anita herself by excerpts from her unpublished autobiography, voiced by Scarlett Johansson.

Pallenberg does not come off well in some Stones biographies, but is represented in a more positive light here, though not a sanitized one. Several insiders testify to her magnetism, intelligence, and skills (if curtailed by her concentration on family life and Richards’s reluctance for her to work) as an actress, as seen in a few clips of her films, some rare. Her problems with drugs and the responsibilities of motherhood are not overlooked, and nor is the incident in the late 1970s in which a young man killed himself in her home. Of note are details on her influence on a few Rolling Stones songs, including “Sister Morphine,” “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” and “You Got the Silver.” The voiced excerpts from her memoir are interesting and articulate, making one wonder if there’s any chance the book can be published, and why it hasn’t appeared.

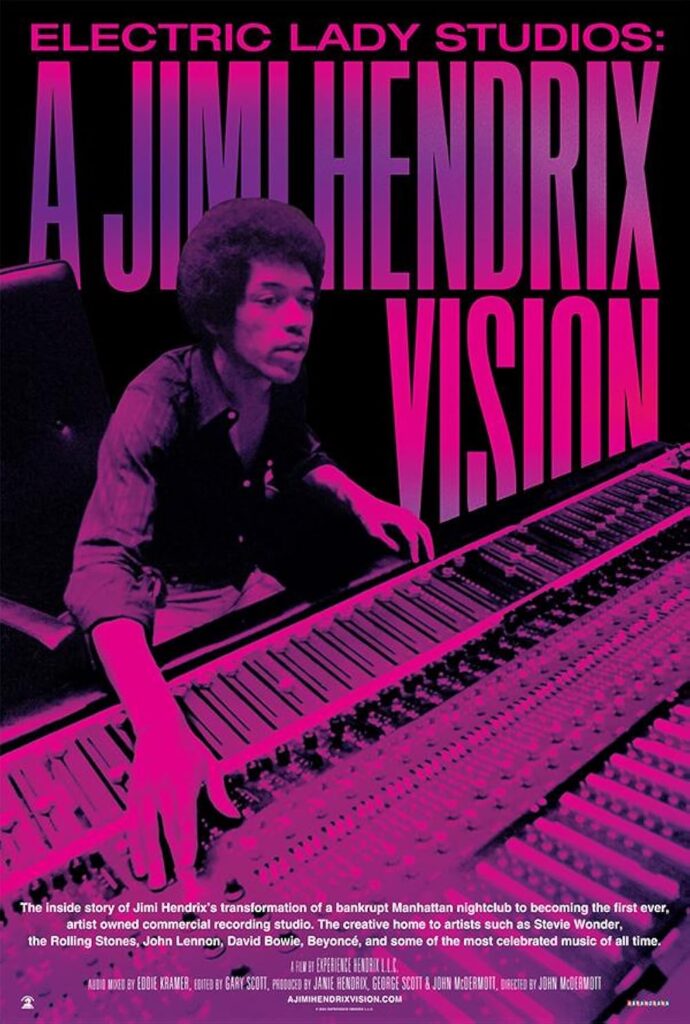

6. Electric Lady Studios: A Jimi Hendrix Vision. New York’s Electric Lady Studios, still going today, was constructed specifically for Jimi Hendrix’s wishes and needs, though he only got to use it a little after its mid-1970 opening, and it was used by other artists from the start. This documentary is available as a Blu-ray disc in a four-disc box of the same title including three CDs of material Hendrix recorded at Electric Ladyland in mid-1970s (though some of it built upon slightly earlier tracks), most of it previously unreleased. As this movie did play in theaters, and is worth a detailed review of its own, I’m reviewing it within this video roundup. A review focusing on the music on the three CDs will be included in this blog’s roundup of the year’s notable reissue albums.

The film focuses on how Electric Lady was conceived and constructed, and what Hendrix managed to record and work on there before his September 1970 death. As Hendrix documentaries go, this is pretty specialized, and even more so than the recent documentary on Hendrix in Maui that was also directed by Hendrix author and authority John McDermott. But if you’re heavily into Hendrix, this is fairly interesting, with interviews (both recent and archival) with a wealth of figures, including most prominently engineer Eddie Kramer. Bassist Billy Cox and several early Electric Lady engineers, designers, and staff also participate, and there’s some (if not much) seldom seen vintage footage of Jimi and related subjects from the era, as well as many pictures of the studio under construction.

One of the best stories, from engineer (and ex-Amboy Dukes drummer) Dave Palmer, is how he lived right across the street from the studios, and was woken by a phone call from Kramer instructing him to get right over at a moment’s notice because Hendrix was recording with Stevie Winwood and a drummer was immediately needed. One of the most surprising side notes is that some of the first recordings done in the studio were for an album based around readings from the book The Joy of Sex. Kramer and Palmer isolate and highlight some aspects of the album Hendrix was finishing (which he never did, though many recordings from the sessions were posthumously issued) at Electric Lady in 1970. It’s also clearly illustrated how complicated it was to build and complete the studios, with constant shortages of cash forcing Hendrix to raise money on the road and borrow against royalties, and mistakes and misjudgements on where to build and what equipment to use costing time and money. This doesn’t go into the many artists recording albums in Electric Lady over the last half century, but does cover some early such sessions, particularly for Carly Simon and Stevie Wonder.

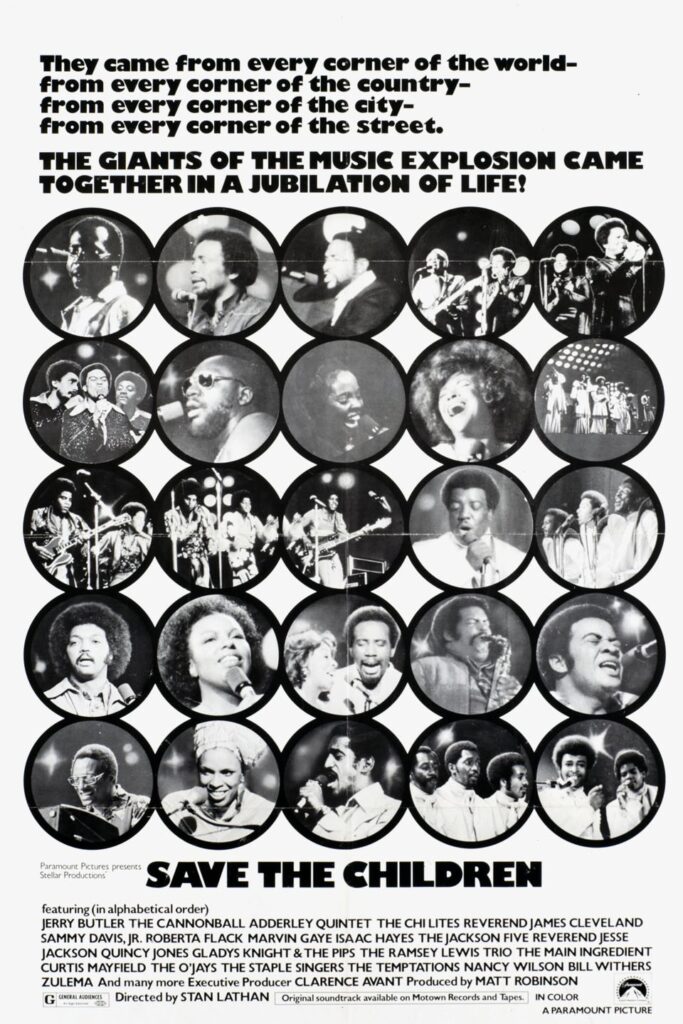

7. Save the Children: A Concert for the Ages (Netflix). Should this be considered a mere restoration of an obscure film, or an actual 2024 re-release? And a 2024 one, since it bills 2023 as the year of its restoration, but wasn’t readily accessible until it streamed on Netflix the following year? Since not many saw this documentary of performances at the 1972 Operation PUSH exposition in Chicago when it came out in 1973, and the restoration didn’t get a ton of publicity, I feel it’s appropriate to place this in the regular 2024 listings. Founded by Jesse Jackson (who appears in the documentary), PUSH stood for People United to Save Humanity. As part of its 1972 expo, many African-American entertainers performed, primarily soul acts, though there were others as well. Excerpts from their performances are the basis of this two-hour film.

The lineup is extraordinary, and as close to what was (not all that accurately) sometimes termed the “Black Woodstock” as the 1969 Harlem performances featured in the Summer of Soul documentary. It includes Marvin Gaye, the Temptations, Jerry Butler, the Jackson 5, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Curtis Mayfield, Bill Withers, the O’Jays, the Chi-Lites, and the Main Ingredient. On the jazzier side, there’s Cannonball Adderley, Roberta Flack, Nancy Wilson, Ramsey Lewis, and Sammy Davis Jr., whose introduction acknowledges (to some negative response from the audience) that his political views—he supported Richard Nixon for president—were not among the most welcome in such a crowd. Highlights include Gaye’s live version of “What’s Going On,” with legendary Motown session bassist James Jamerson in the band; the outrageously colorful space suit-like wardrobe of the O’Jays; Knight’s almost hyperfast arrangement of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine”; Mayfield’s guitar work with a live band as he approached his Superfly era; the Temptations’ vocal interplay on “Papa Was a Rolling Stone”; the Chi-Lites’ use of a melodica onstage; and the strong soul of one of the least known performers featured, Zulema.

This isn’t as strong a cinematic work as Summer of Soul or Wattstax. The concert excerpts are sometimes too short; there are frequent interspersions of footage of African-American urban life, sometimes cut to while the soundtrack of performances continues to play; and too-long scenes featuring gospel and Jackson’s speeches. But this certainly ranks among the top soul music concert documentaries of the era. While the publicity for it, like it was for Summer of Soul, trumpeted how it was virtually lost and rescued, in fact some performances have been used for DVD compilations of clips by the Temptations and Marvin Gaye.

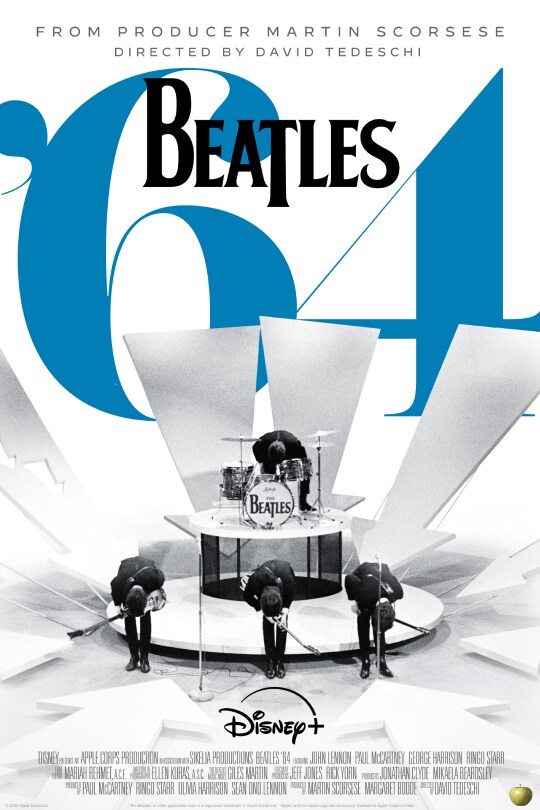

8. Beatles ’64 (Disney +). When the Beatles first came to the US in February 1964, their trip was followed by filmmakers Albert and David Maysles for the TV documentary What’s Happening!: The Beatles in the U.S.A. This more extensive production is kind of like watching an expanded version with a lot of additional context that makes the action easier to follow. Besides a lot of footage from the Maysles’ movie, there are clips from their Ed Sullivan Show appearances and first US concert in Washington, DC; short clips from archival interviews with the Beatles and Carnegie Hall show promoter Sid Bernstein; and recent interviews done specifically for this documentary. Much of the footage from What’s Happening! and the Sullivan shows/DC concert will be familiar to many Beatles fans – not just intense Beatlemaniacs, but plenty who are more general dedicated admirers of the group, since it’s been available in several formats for years.

So a little surprisingly, considering modern linking interviews are often the weakest part of such documentaries, those interviews are the most interesting segments for snobs like me who’ve seen it all before, or seen most of it. Besides memories from Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, there are brief but worthwhile observations about the Beatles’ relation to African-American music from Smokey Robinson and Ronald Isley. One of the fans seen screaming for the Beatles outside their New York hotel in the 1964 documentary was tracked down for her comments. So was Jack Douglas, who’d work with John Lennon as a producer, but as a mid-1960s teenager went with a friend to Liverpool to play music there with a friend. Even for viewers who might not find out much from this film, it’s an okay overview worth seeing, if those who haven’t seen the Maysles documentary will find it fresher and more exciting.

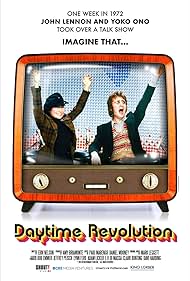

9. Daytime Revolution. In February 1972, John Lennon and Yoko Ono co-hosted Mike Douglas’s daytime talk show. Besides being interviewed by Douglas and performing some songs, they also brought on quite a few adventurous and eclectic guests. Although this documentary has quite a few clips from the shows, its main value isn’t in that footage, as the complete episodes were issued on home video quite a few years ago. The segments of highest interest are recent interviews with many of the participants, including an associate producer of the program and guests, including Ralph Nader, avant-garde musician David Rosenboom, a Japanese-American singer/activist, a macrobiotic chef, and a biofeedback researcher. Unfortunately Ono wasn’t interviewed, but besides discussion of the appearances of these figures on the show, there’s also commentary about some of the other colorful and famous guests, those being Chuck Berry, Bobby Seale, Jerry Rubin, and George Carlin. It’s hard to believe Lennon, Ono, and their friends were given so much airtime, but they generally made good use of it, with Douglas being a sympathetic and efficient interviewer, though he was of a different generation than the counterculture the couple and their guests represented. The film effectively alternates clips from the show with interviews done for the project, letting the footage and the interviews tell the story without undue embellishment or interference.

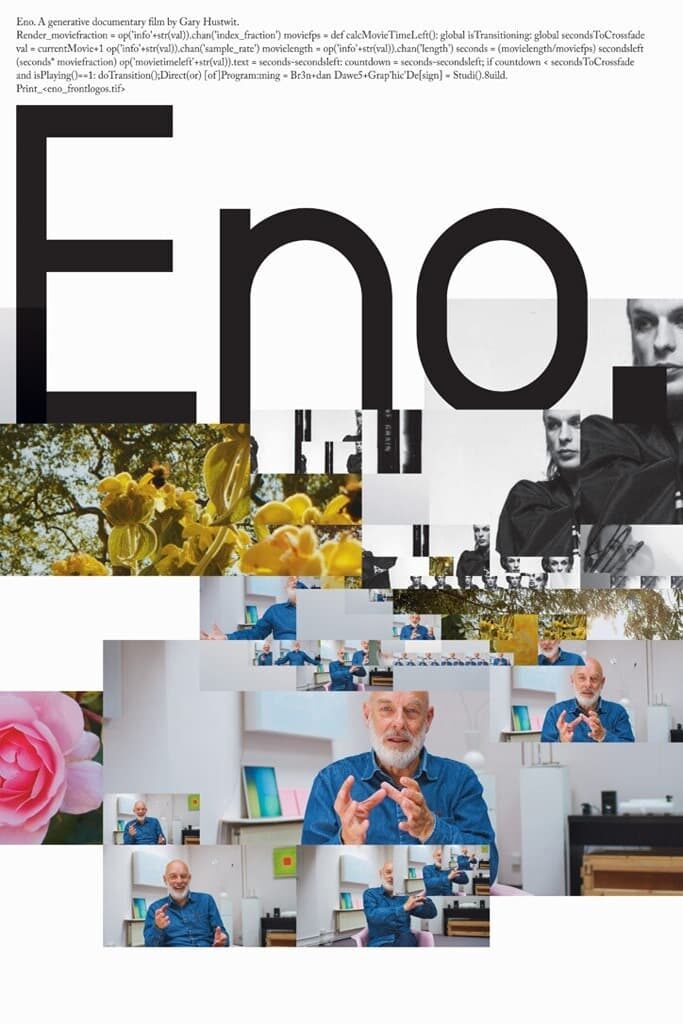

10. Eno. Even with all of the reviews I’ve done in my career, this is one unlike any other. As many already know, every screening of this Brian Eno documentary is different, as it’s generated by a software program. There are no less than 52 quintillion possible variations, which in layperson’s terms is literally a billion billion. So if everyone on the planet spent their whole lives generating and watching variations, they wouldn’t come close to seeing every one. It also means that every reviewer will have seen a different version, or different versions, even if they’re dedicated enough to go to ten or twenty screenings. Considering they draw from thirty hours of Eno interviews and 500 hours of footage from Eno’s archive, it would take a few months to get through all of that raw material even if you spent all of your working weeks doing nothing but watching that.

My review’s based on just one puny viewing of a 90-minute variation. As wary as I was about the enterprise given its unique format, my expectations were surpassed. Even being aware a lot of possibilities weren’t being shown, it covered a lot of material in a pretty engaging, if non-linear and non-super-in-depth way, from his art school roots and Roxy Music through his brief time as a solo glam (at least in image) rocker, his ambient music for airports, his first public lecture (a much more enjoyable segment than that might sound), and his collaborations with David Bowie, Talking Heads, Devo, and others. Whether in recent or archive interviews, Eno talks in an articulate but humorous, down-to-earth fashion, even when espousing some philosophical musings about the meaning of music and art. The transitions are sometimes a bit bumpy, but usually the segments, often separated by computer text, could stand on their own. So could the variation I saw, though many viewers and critics would have been wondering why some notable projects, like his My Life with the Bush of Ghosts collaboration with David Byrne and his production of the No New York no wave compilation, weren’t even mentioned.

Presumably those and quite a few other aspects of his career that were missing or glanced over are covered in other variations of the film. From a friend who has seen two screenings, I did hear that at least based on those, there’s more overlap between variations than you might expect given the publicity about the Carl Sagan-type numbers, though there were significant differences too. I’m not going to try to see 52 quintillion ones, or even 52, but I wouldn’t mind seeing a couple others down the line, especially if it goes into streaming, which is being worked on despite the technical challenges.

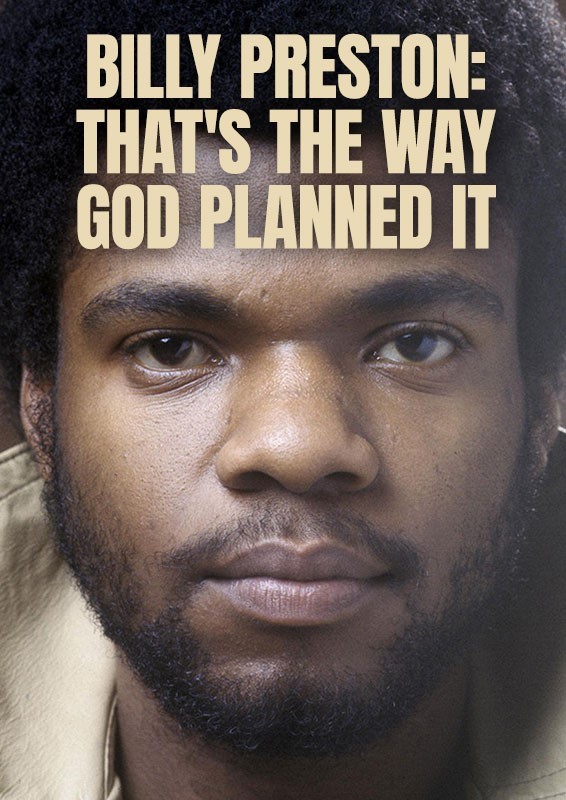

11. Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned It. Considering he had notable stints as a sideman with both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and that he had some huge hit records as a solo artist, Preston hasn’t gotten a great deal of historical attention. This documentary goes some way to making up for that, but isn’t as good as it could have been. On the good side, there’s a lot of archive footage, some of it rarely seen and amazing, like his appearance on the Soul! TV show; his appearance as a pre-teen on Nat King Cole’s variety show; clips of his mother playing and singing; and the more expected bits of him with the Beatles in January 1969 and at the Concert for Bangladesh. There are snippets of archive interviews with Preston, but quite a few recent ones, ranging from major figures like Eric Clapton and Ringo Starr to soul singers Gloria Jones and Merry Clayton, along with family, friends, and associates not known to the public.

While the essence of Preston’s considerable talents at blending soul, rock, and gospel come across, the first half is certainly better than the second, which charts his descent into drug abuse, health problems, prison, and a struggle to remain in the music business. Most of his career highlights are here, but sometimes presented in a fashion that makes it hard to track the sequence of events; his guest appearance on John Lennon’s “Instant Karma” pops up after later events in the first half of the 1970s. Not discussed are his release of “My Sweet Lord” and “All Things Pass” prior to George Harrison’s far more famous versions; his contributions to Starr’s Ringo album, including playing on “I’m the Greatest” with Starr, Harrison, and Lennon; or “Melody,” the song on which Preston made his most significant contribution to the Rolling Stones.

Maybe this is the griping of a music nerd who doesn’t care as much about his personal difficulties as his music, though those problems, including struggles with his sexual identity, have their place in a documentary. Those issues are drawn out longer than they should be in the film’s final sections. It’s interesting to learn, however, that a planned autobiography co-written with David Ritz didn’t happen owing to what Ritz describes as Preston’s reluctance to go deep into personal matters, and that his cover of the Beatles’ “Blackbird” was considered as the A-side to the single that became a massive hit, “Will It Go Round in Circles.”

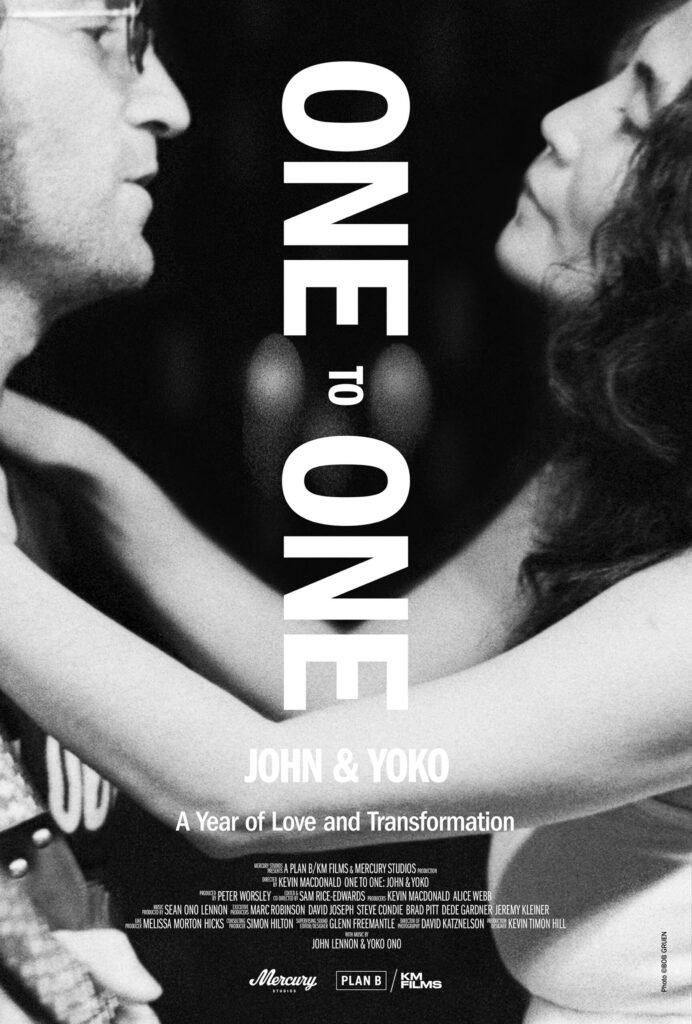

12. One to One: John & Yoko. A few documentaries have covered and/or even focused on John Lennon and Yoko Ono in the early 1970s, including one, Daytime Revolution, that’s higher on this list. Here’s another one, and while there’s some overlap with other documentaries (though not much with Daytime Revolution), there are some differences in the content and approach. I hadn’t heard the term “mixtape” applied to movies as well as musical efforts, but this film was repeatedly referred to as one at the special screening where I saw it. From my understanding, this means a movie that not only addresses its principal subject, but also adds a lot of almost soundbite-style clips related to the era or subject, quickly switching back and forth between them. The director appeared at the screening I saw, and noted it was at least in part inspired by John and Yoko’s frequent television watching at the time, since the scenes are constantly changing and separated by the kind of fuzzy white noise frames you see when the television is between channels.

One to One: John & Yoko is named after the benefit concerts they gave on August 30, 1972 in New York for a nearby facility for intellectually impaired children. These were the only full-length shows Lennon gave after the Beatles split, but although there’s a fair amount of footage from them in this film, it’s not exactly the focus. Songs from the concert are interspersed throughout the movie, but the film doesn’t discuss how and why it was staged until relatively late in the proceedings. This is more a look at Lennon and Ono’s time in New York in 1971 and 1972, when they were at their most politically active, and when that activism was most specifically reflected in their music, though most critics and listeners (including this one) feel that their 1972 album Sometime in New York was a major disappointment, and a low point in Lennon’s catalog.

Although the concert footage is pretty good, the most interesting aspects of this documentary are the rarest or previously unheard/unseen components. These aren’t so much the home movies as excerpts from recently unearthed tapes of telephone conversations, including bits with well known figures like Allen Klein, May Pang, Jerry Rubin, and creepy Dylanologist A.J. Weberman. As my favorite example, Lennon explains to Klein he wants to do a concert tour where a quarter of the money goes toward bailing out prisoners; Klein doesn’t respond as a hard-boiled businessman, but matter-of-factly seems to be affirming and going along with John’s plan. Which didn’t come off; as the film later notes, Lennon called off the tour, in part because he was alienated from radicals like Rubin by plans for protesting the Republican convention that might have endangered people with violence, including children.

The many short clips that aren’t specifically related to John and Yoko range from Jerry Rubin on a talk show, the attempted assassination of George Wallace, and Shirley Chisholm’s presidential campaign to tacky period commercials and Attica prison riots. There’s too much of this contextual material, and while what Lennon and Ono were up to at this time is interesting regardless of the quality of the music they were making, there’s not a whole lot here that dedicated fans won’t know from books and other documentaries. Although Stevie Wonder’s briefly seen in this documentary at a rally for John Sinclair where John and Yoko also performed, it doesn’t mention that Roberta Flack also appeared. And quite a bit of footage from the actual One to One concert was made available on VHS back in 1986 on the John Lennon Live in New York City video. While this is worthwhile for Lennon/Ono fans and provides a lot of background to the era and their activism for viewers who might not know a lot of the history, it’s generally more hectic and variable that it needs to or should be. It might not be widely seen soon; I attended only the second US screening at a documentary series, and while the director hopes to have it picked up by a distributor in 2025, he said it might take longer than that.

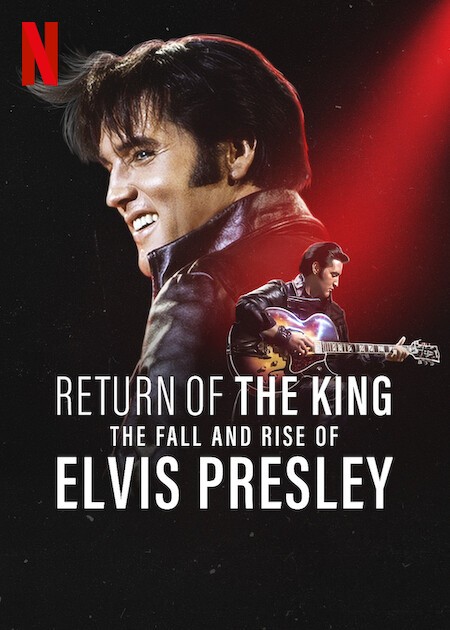

13. Return of the King: The Fall and Rise of Elvis Presley (Netflix). This is different from the usual Elvis Presley documentary in that much of the focus is on his fallow years—the decade or so between his induction into the army and his 1968 TV comeback special. Thus the title “the fall and rise,” without too much material on his initial rise. There’s more than most Elvis biographical projects have—quite a bit, encompassing most of the 1960s—on the years in which he didn’t perform live and was mostly occupied with poor and progressively worse movies. The presentation could be overcontextualized, with too many table-setting interviews with various figures—some famous, some who didn’t have any direct relation to Elvis—explaining why he was so talented and important. There are, however, some good inside comments from Priscilla Presley and Elvis’s friend Jerry Schilling, along with more general observations about Presley’s significance from the likes of Bruce Springsteen and Conan O’Brien.

While his comeback on a 1968 network TV special takes a lot of time in the film’s final sections, note that it’s examined in greater depth in the 2023 documentary Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback, which has interviews with some figures (notably director Steve Binder) not represented in Return of the King. Coverage of the TV special in Return of the King is notable for including some outtake footage indicating how nervous he initially was at the prospect of performing before a live audience for the first time in seven years, and how he flubbed some attempts at takes in skits in which he might have been nearly as engaged. There are a couple of uncommon perspectives about his comeback, one being that his 1967 gospel album How Great Thou Art—not usually regarded as a career highlight—is seen as a turning point in Presley returning to what inspired him most, though singles like “Guitar Man” and “U.S. Male” are more often cited as recordings indicating he was ready to rock out again. Also, and refreshingly, it’s pointed out that the skits in the comeback special aren’t that good and more representative of what manager Tom Parker would have wanted the program to present than the famous live sequences of him performing before a small audience.

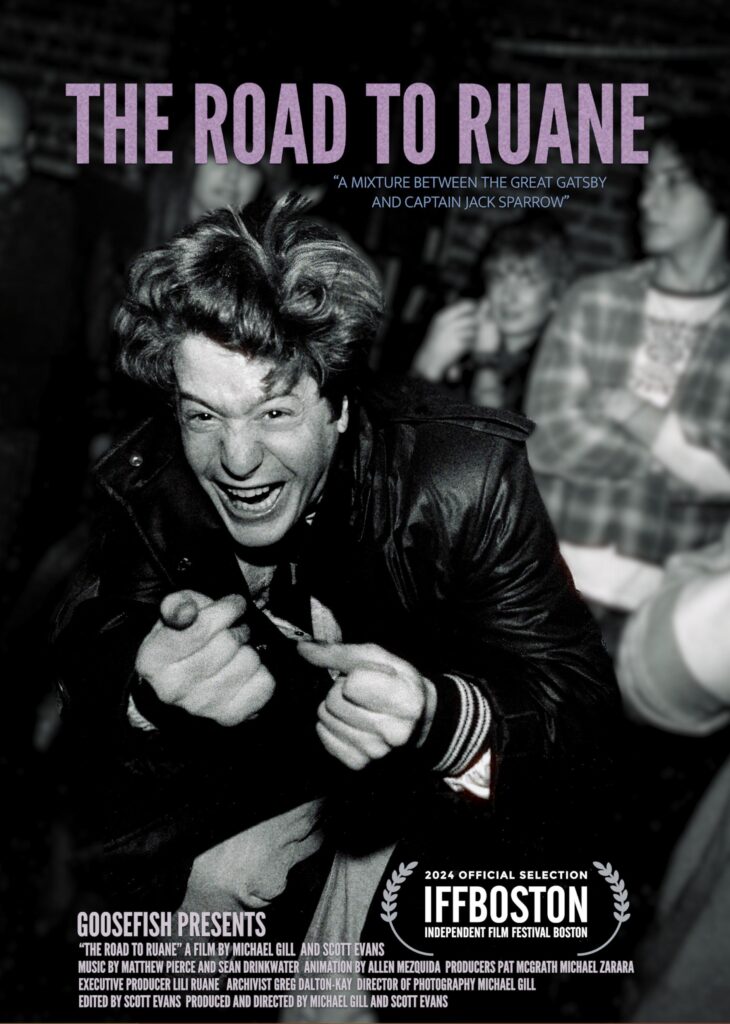

14. The Road to Ruane. Except perhaps in Boston, Billy Ruane isn’t a name known to most rock fans. He promoted a lot of underground rock shows by both local and touring acts in Boston in the 1990s, and there’s footage of a lot of them in this film. That might not sound like the most exciting subject for a documentary, especially if you’re not particularly a fan of this scene—the numerous brief clips range from barely known names to the likes of Sonic Youth, the Pixies, Elliott Smith, and lesser knowns like the Volcano Suns, Buffalo Tom, and Mary Lou Lord, to give you an idea. But this is a pretty interesting and well made movie no matter what your musical taste and knowledge, as the primary focus—particularly after the first section, which does emphasize such footage—is not so much on the local music as the unusual life and character of Ruane himself.

Ruane was manic depressive, and though that might have fired his manic enthusiasm for music (not just underground rock, though that’s what he was most involved in as a professional), it probably made him hard to be around for most people. He’s often athletically dancing to shows (including those he promoted) in the archive footage, and while that’s fun to watch, it might not have always been such fun to experience when he got out of control, which wasn’t that rare. Like many such behind-the-scenes movers and shakers, he was also a manic collector. Unlike all such movers and shakers, he could be exceedingly generous, often paying acts way more than they were getting elsewhere, or far more than they expected. He also helped out musicians and friends quite a bit otherwise, often financially.

How could he do this? He was a rogue son of a very successful financial professional who had ties to Warren Buffett. That wasn’t as much of a benefit as it might sound, since he also had a troubled family life, which found his mother committing suicide when he was 18, and Ruane himself developing symptoms of instability and mental illness from a young age. That led to his premature decline and death in middle age, an uncomfortable period that is nonetheless covered though not overemphasized near the end of the film. The production includes an incredible wealth of interviews with musicians and associates for such a relatively non-famous figure, including some pretty well known ones (Peter Wolf, J. Mascis, Thurston Moore), but a wealth of unfamiliar names with something of interest to say or remember. The interviews and archive footage are blended well for this well made film, although it might be a bit longer than the topic merits.

15. Something in the Air: A Rock Radio Revolution. Although this has had a few screenings, it’s not in general release and is in fact still fundraising for completion to its final form. Nonetheless, I did see it in a San Francisco movie theater this year, and assuming it will be similar to what I saw if it gains wider release, I’m reviewing it here. This documentary covers the most famous San Francisco rock radio station, KSAN, as well as the brief early time much of its staff worked at KMPX before moving to KSAN after disputes with KMPX ownership. There were a few underground FM rock stations that originated throughout the US when KMPX adopted that format in 1967. But KMPX and then (after much of the staff jumped ship to a different frequency in 1968) KSAN might have been the most celebrated of those anywhere. That was due to both their freewheeling content and the big audience it had in the Bay Area, feeding off the heyday of the region’s psychedelic sound live and on record.

The film has interviews with many of the station’s DJs, newscasters, and other staff, some of whom have died since they were filmed for the project. Those interviewed include some of the most famous on-air personalities, including Raechel Donahue (widow of Tom Donahue, who did more than anyone to launch the format), DJ Dusty Street, newscaster Scoop Nisker, musicians (including a few big names like Carlos Santana), and rock journalists Ben Fong-Torres (also sometimes a DJ) and Joel Selvin. There’s not a whole lot of vintage footage, but there’s some, and Tom Donahue’s path from AM radio DJ/record label owner/show promoter to countercultural icon is traced. There are amusing stories, some but not all drug-related, about the looseness of the on-air programming, as well as their key coverage of the Symbionese Liberation Army when the station was given tapes by fugitives in the SLA.

The more troubled late-‘70s era when KSAN both pioneered some commercial new wave radio programming and found it difficult to balance with the older forms of rock with which it had been established is also discussed. So is its unwelcome transition to a country format in the early 1980s, when the very counterculture that had fueled the format’s rise was dissipating. The focus does sometimes go back and forth chronologically a little haphazardly, sometimes jumping from the hippie era to early punk and new wave and back again. It’s also hard to get excited about how KSAN’s airing of early material by Montrose was daring and significant, though the station’s frequent broadcasting of live shows is justly praised. Overall this is a reasonable overview of an important and groundbreaking station (or stations, if you’re counting both KMPX and KSAN), though in need of some more polish.

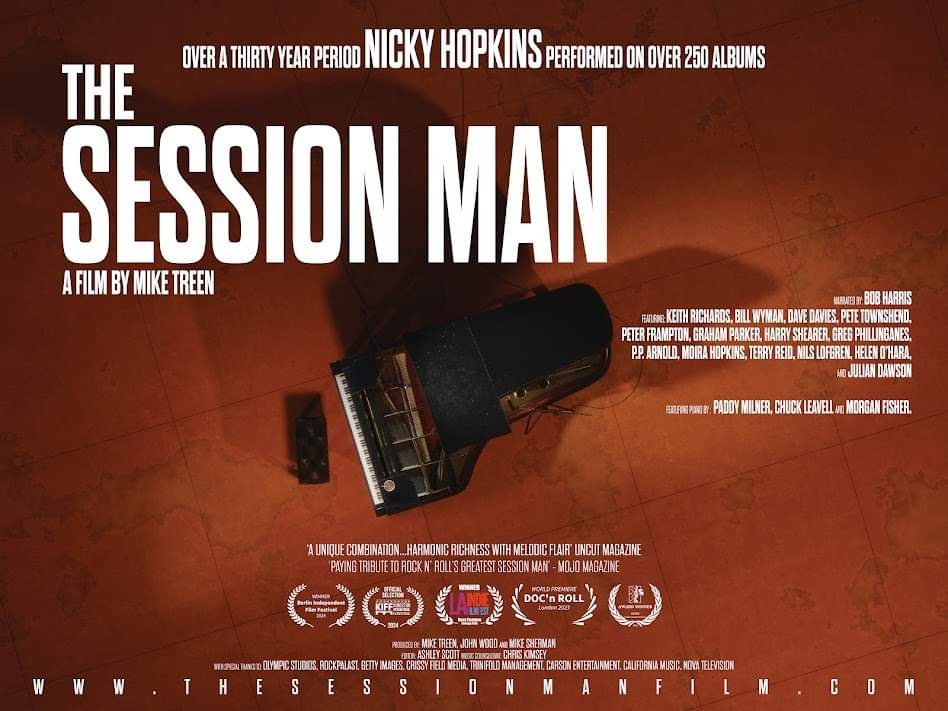

16. The Session Man. The session man is Nicky Hopkins, the great British keyboardist who played on sessions for many classic records in the 1960s and 1970s, including ones by the Who, the Kinks, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles (just once, on “Revolution”), Jefferson Airplane, John Lennon, George Harrison, Ringo Starr, and others. He was also a member of the Jeff Beck Group and Quicksilver Messenger Service for a while, and even sort of honored by Ray Davies on the Kinks song “Session Man,” on which he played. This fairly interesting documentary has quite a list of interviewees remembering Hopkins and testifying to his gifts, including Dave Davies, Keith Richards, Jorma Kaukonen, Bill Wyman, engineer/producer Glyn Johns, producer Shel Talmy, Graham Parker, and (by archive footage) Mick Jagger. There are also substantial excerpts of a couple interviews Hopkins himself gave late in his life and one done for this film with his second wife, as well as comments by lesser known musicians, some of whom demonstrate famous Hopkins piano parts.

As a film, it’s not as great as the list of contributors. The excerpts of sound recordings on which Hopkins played are very short and usually in the background of the soundtrack. This seems partly why it’s left to those not-so-well-known pianists to play famous parts like those Nicky played on the Rolling Stones’ “She’s a Rainbow” and “Sympathy for the Devil” (and the not as famous one he did for the Who’s “The Ox”). There’s not much footage of Hopkins himself playing in his prime, though he’s glimpsed in short snippets of the Stones working in the studio in 1968 that appeared in One Plus One (aka Sympathy for the Devil). The segments are separated by sections in which his credits for specific artists are briefly on the screen, which then goes to black before the next part is announced with the title of the artist. That’s a picky criticism, yes, but it gets tiring when the device is used over and over.

Hopkins made important contributions to many records, but wasn’t the most colorful guy. Many of the comments are similar in general praise of his versatility and ability to blend rock, blues, and classical style, but short on specific neat stories. It’s noted that his affliction with Crohn’s disease sometimes made it difficult for him to work and contributed to his death at age fifty, and also that Chick Corea was responsible for getting him into rehab, which likely extended his life. According to one interview, Hopkins was offered a place in Wings, but didn’t pursue it when told he had to audition—a story I’ve never come across in Paul McCartney literature, of which I’ve read quite a bit. Again this will strike some as picky, but the narrator says at this point that McCartney had known him for more than twenty years when he made this offer—impossible, since even if that was at the very end of Wings’ lifespan, that would have meant they’d known each other since around the late 1950s. Maybe it was meant Paul made an offer to join his band in the late 1980s when Hopkins did play on a McCartney album, but Wings had long since disbanded then, and it’s a sloppy mistake.

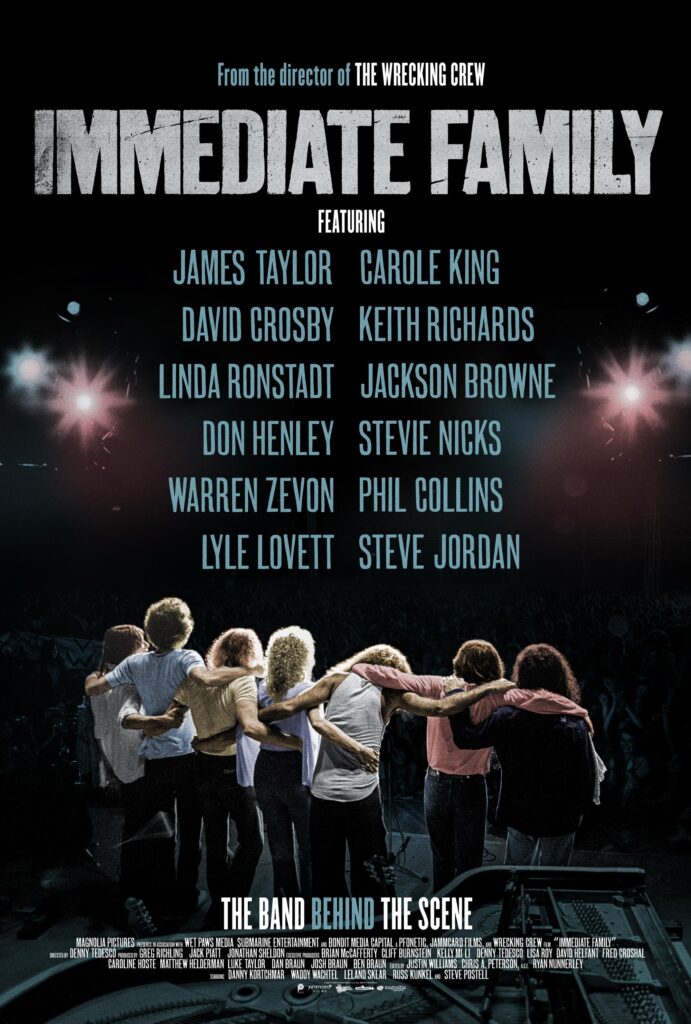

17. Immediate Family (Magnolia). This started to do the round of festivals in 2022, but the 2024 Blu-Ray has a lot of bonus content, which is enough to get it into this list. Immediate Family is the name given to a clique of L.A. session musicians, a la what the Wrecking Crew had been in the 1960s, who played on many records in the 1970s – and also beyond, though the ‘70s albums on which they appear are the most renowned. These included albums, some very famous, by the likes of Carole King, Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, James Taylor, and Warren Zevon. Immediate Family have toured on their own in recent years, and members are interviewed in this documentary, including drummer Russ Kunkel, bassist Leland Sklar, guitarist Danny Kortchmar, and guitarist Waddy Wachtel. So are a good number of the musicians and producers they worked with, including King, Browne, Ronstadt, Taylor, David Crosby, and producers Peter Asher and Lou Adler.

In keeping with the music they played, this film, or at least the first and best part of it, is solid but not spectacular. There’s a bit of footage of the stars and their sidemen from back in the ‘70s, but the bulk of it is devoted to interviews articulating their memories of how they became a go-to team in Hollywood studios. Not all of it’s just about hits like Tapestry and Sweet Baby James; Kortchmar’s roots in the King Bees and the Flying Machine, and Kunkel’s in Things to Come, are noted if not discussed in too much depth. There are also quite a few touring stories, as they’d often back musicians like Browne on the road, and while they might be holding back some of the more salacious ones, there’s an unexpected account of Linda Ronstadt enthusiastically joining with the boys to check out a strip club (and her being required to sing a bit to gain entrance as she didn’t have an ID). After the first hour, the 100-minute doc gets less interesting as it gets into the 1980s and slicker music (which endangered many sessioneers’ living) with the likes of Phil Collins, as well as some coverage of the recent live shows by Immediate Family.

The extras on the Blu-Ray aren’t incidental, adding up to three hours, according to the back cover blurb. An hour of this presents a roundtable discussion between all of the Immediate Family members that, unlike many such things, is coherent and fairly interesting, avoiding having them speak over each other or make silly in-jokes. Most of the rest has extended interview material with people who are interviewed in the documentary—not Immediate Family, but the stars they backed and associated producers, too. While some of this content is of limited appeal, there are some observations and stories of value, like detailed comments on James Taylor’s guitar style, and Kortchmar’s take on whether Taylor wanted to be in a band or go solo. These interview segments (though not the roundtable discussion) are hindered, however, by a ten-second ad of sorts separating each and every part of the specific interviews, flashing logos and sites associated with the documentary while the exact same instrumental passage plays. This doesn’t just happen a few times; it happens dozens of times. It’s an annoyance that’s rude to the viewer.

18. Brenda Lee: Rockin’ Around: American Masters (PBS). Like some other American Masters episodes, this flashes by the highlights—or some of them, anyway—of a career of a major artist pretty quickly, inevitably providing only a partial picture. As this is just an hour long, that’s more of an issue here than it is in some of the series’ longer episodes. It also zigzags quite a bit in her chronology, and although there are some performance clips, they are very brief—a shame, since some of them are pretty rare to my knowledge, like one of a very young Lee singing “Hound Dog” (which she didn’t put on her records). It does, however, have quite a bit of recent interview footage with Brenda in which she discusses her tough upbringing, the challenges of being a young star, and not only pioneering the role of women in rock, but also going into other genres, particularly country. The only significant peer from her prime among the other interviewees is Jackie DeShannon, who has some good comments about songs she wrote that Lee covered, as well as about Brenda’s general artistic stature. Other interviewees are mostly stars testifying to her influence, none of whom (Pat Benatar, Trisha Yearwood, Keith Urban, Tanya Tucker) were old enough to be performing during Lee’s prime. Although, to be fair, not many of the people who worked with her in the 1950s and 1960s, like producer Owen Bradley, are still around.

The co-author of Lee’s autobiography, incidentally, claims that she had more double-sided hits on singles than anyone. That’s not so; Elvis Presley certainly had more, as did others including Ricky Nelson and Pat Boone, even if you’re limiting yourself to the mid-1950s through the mid-1960s. Lee says she was the first woman rocker, and while she was the first big female rock star (unless perhaps you count Connie Francis as a rock singer), as far as being the first, certainly LaVern Baker predated her; Wanda Jackson did her first rock records around the same time; and some more obscure women rockers debuted around the time Lee did. Her achievements are enough to stand on their own without being inflated. And it’s too bad this documentary somehow didn’t mention that she recorded a 1964 hit single, “Is It True,” in England with then-session man Jimmy Page on guitar.

19. Wes Bound: The Genius of Wes Montgomery (PBS). This modest hour-long documentary is a reminder that for some major musical artists of the 1950s and 1960s, there aren’t many people around any longer to supply first-hand memories. So it is for Wes Montgomery, often acclaimed as one of the greatest jazz guitarists, though few survive who worked with him. While this relies on testimonials from others about his music — a couple quite famous (George Benson and Pat Metheny), more often quite obscure — this does cover the outlines of his career, with his son Robert providing much of the linking context and commentary. Montgomery wasn’t filmed terribly often either, but this does have some excerpts of his work from 1965 European performances (available in much greater length on the Live in ’65 DVD), a much earlier solo he took while in Lionel Hampton’s band, and a 1968 interview conducted shortly before his death.

20. Disco: Soundtrack of a Revolution (PBS/BBC). Lasting almost three hours, this three-part series covers disco’s birth and heyday in the usual competent PBS/BBC fashion. There’s plenty of archive footage of performers and clubs, and lots of interviews with figures who were important in the genre, from artists, session musicians, and producers to DJs, clubgoers, and journalists. Maybe it’s a little more geared toward rapid cuts from soundbites than other public television music documentaries, owing to the party pace of the subject. There’s a wide range of commentary on the music from several angles, from drummer Earl Young demonstrating the construction of disco’s signature beat to singers like George McRae, Nona Hendryx, Candi Staton, and Anita Ward, producer Tom Moulton, and journalist Vince Aletti. Aside from the music and records, much attention’s given to its roots in gay and black clubs, as well as famed clubs and spaces like Studio 54; the prominent role of black women as disco artists; and the backlash against disco as the 1970s ended.

Certainly there are plenty of figures who aren’t covered, from producers like Giorgio Moroder to artists like Boney M. and Silver Convention, and the European branch of disco isn’t covered to any significant degree. The section on house and disco offshoots at the end could have been shortened. Plenty of territory is covered in the space allotted, however, making it of musical and social interest even for viewers who aren’t especially disco fans.

The following movies came out in 2023 (and perhaps 2022 depending on what release date you see), but I didn’t see them until 2024:

1. Jerry Lee Lewis, Trouble in Mind. This has an official release date of 2022, but really it didn’t seem to be widely seen and streamed until 2024. Putting it in the 2023 section splits the difference. This is unconventionally structured for a documentary as it doesn’t tell a linear story, or use narration or interviews done specifically for the film. Instead there are a wealth of vintage performance clips—some complete, more often excerpted—along with an abundance of vintage interview clips, usually brief soundbites, with Lewis. There are also brief bits of interviews with associates like Lewis’s sister, but it’s almost entirely Jerry Lee’s show. The clips span almost his entire career, from his 1957 performance of “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” on the Steve Allen show—shown in its entirety, and tremendously exciting—to a 2020 song when he was close to death. Both his rock’n’roll and country material/incarnations are covered. There are also some duet performances, including ones with his cousin Mickey Gilley and Little Richard.

Since there’s generally too much in the way of unnecessary and even irrelevant commentary/narration in music documentaries, I generally approve of letting the music and artist speak for themselves. That generally works here, in part because Lewis was a very good and consistent performer, though you sometimes wish the performance excerpts were longer. The pluses considerably outweigh the flaws in this film, but it could be said that it’s on the short side at 73 minutes, and there’s certainly enough fine Lewis on film to fill more time. Some of the cuts between different versions of the same song are a bit hectic. While Lewis is generally witty (and unrepentant) in discussing his career with interviewers, these observations are brief and disconnected enough to make it hard for viewers without considerable familiarity with his work to get a full sense of his career trajectory and accomplishments. There are books, if imperfect ones, to fill in those gaps. Certainly Jerry Lee isn’t shy at taking credit for his greatness in what we hear on screen in this documentary, if uncomfortably blithe in talking about some of the more controversial aspects of his life.

2. Lost Angel: The Genius of Judee Sill (Greenwich Entertainment). Sill only had a couple singer-songwriter albums in the early 1970s, but has generated a sizable cult following in the twenty-first century. Her discography is slim, though it’s been embellished by some unreleased material and live recordings. But there’s enough archival material—including some performance footage (though some of it’s in lo-fi black and white), audio interviews, and diary entries (here voiced rather than read by Sill)—to form a substantial part of this hour and a half documentary. More of it’s devoted to comments from people who knew and worked with Sill, and the roster of interviewees is impressive, including Graham Nash, Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, David Crosby, David Geffen, and Jim Pons of the Leaves/Turtles, along with far less celebrated musical colleagues and friends. There’s also praise from younger musicians who admire Sill’s music, and while her two albums and touring during the early-1970s are detailed, so are her harrowing experiences before and after her brief recording career. Those include extensive drug use, at least some time as a prostitute, and severe physical pain from car accidents and surgery in her final years, exacerbated by her failure to gain a record deal after her two LPs for the Asylum label.

While this is a solid documentary—especially considering there wasn’t abundant source material with which to work—it might not convince viewers such as myself who don’t rate Sill’s records too highly of her greatness. Sill herself seemed convinced of it, but there was a gap between her goal to quickly ascend to stardom and her modest sales at the time, though she had the backing of Geffen and his then-new Asylum label. There’s speculation Geffen dropped her because of some unflattering remarks she made about him, which the record executive refutes here; as to a story that she camped out on his lawn to pressure him, he notes he didn’t have a lawn. While the praise from Nash, Browne, and Ronstadt is so fulsome it seems at times like they regard Sill as having more talent than they do, there really isn’t a mystery as to why she didn’t become nearly as successful—her music wasn’t as accessible or possessed of nearly as much wide appeal. And, in my opinion, not nearly as good, and unrealistic to view as having failed to connect with the masses because of bad breaks or alleged lack of promotion. Whether or not others agree, the music itself is extensively and intelligently discussed, including her blend of period singer-songwriter rock with gospel, jazz, orchestration, and classical flavors, as well as lyrics that sometimes blended religion with sexuality.

This is, incidentally, another film that first screened in 2022 but didn’t seem to get widely seen until 2024. The DVD has a 2023 copyright date, so I’m putting it in the 2023 section.

3. Carole King, Home Again: Live from the Great Lawn, Central Park, New York City, May 26, 1973 (Ode). Actually first screened in 2022, this didn’t make it onto DVD until 2023. It was shown on PBS a lot too, but the DVD gives you the full 80-minute running time without pledge breaks. It’s a straightforward film of this concert before a large audience, with a sizable introductory segment explaining King’s basic rise to stardom and how the concert was arranged, with voiceover from King and producer Lou Adler. King and Adler occasionally have voiceovers during the main concert portion too, but mostly that’s presented without embellishment. The first half of the performance was devoted to King solo at the piano; in the second half, she was accompanied by a band with jazz-rock fusion flavor, in line with what was at the time her more recent material.

It’s curious there’s no “I Feel the Earth Move” or “So Far Away,” and she didn’t revisit some of the classics she wrote with Gerry Goffin that she redid in her early solo career, like “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” “A Natural Woman,” and “Up on the Roof.” The songs from her about-to-be-released Fantasy album would have been unfamiliar to the audience, which doesn’t seem to mind, and are still not among her more familiar works, other than the small hit single “Corazon.” But King performs well and with ebullience, and there’s none of the drama associated with some outdoor festival or festival-like events of the time, other than some worry about concertgoers climbing towers. The hockey jerseys worn by some of the backup band are not explained.

The Eno doc is great, but frustrating. In the version that I saw dissecting the recording process of one of the songs on Another Green World was the only time any of his four 70s rock LPs were addressed. Those LPs are arguably his most important works. Besides that there was also no mention of John Cale, Cluster, Devo or No New York, and Robert Fripp was only briefly acknowledged in the context of recording Bowie’s “Heroes.” I don’t mind the random, nonlinear aspect of the film, but as a fan I would much rather have seen a 3 hour version that at least touches upon all corners of Eno’s career.

Great to see the Billy Ruane doc included. Billy was a powerhouse in the Boston music scene. Most touring acts of the 80s and 90s will probably remember him fondly.

I basically agree about the Eno doc — no matter what version you see, some notable stuff will be omitted. Also I think many, and maybe the majority, of fans who want to see this in the first place will have the interest and patience to see a much longer variation of the film — three hours, or at least two and a half hours. I think a good number would also pay to be able to stream much of the pool of content that is used in variations on something like a pay-per-straem basis.

Let It Be (1970) was not a very good documentary. First saw it in 1985 then many times after. Also, saw much unreleased footage which was better than the film.

Get Back doc was much more insightful and complete.

Don’t Look Back by DA Pennebaker or Tupac Thug Angel by Peter Spier should have been in this list.

I reviewed Get Back, which I placed at the #1 position, in my post listing my favorite music documentaries from 2021, at http://www.richieunterberger.com/wordpress/top-twenty-or-so-music-history-documentaries-of-2021/. I wrote a long post just on the Get Back documentary itself at http://www.richieunterberger.com/wordpress/the-road-from-get-back-to-let-it-be/. Don’t Look Back and Tupac Thug Angel weren’t considered for this list because this post only covers documentaries released in 2024, with a few from a couple of years before 2024 that I hadn’t seen when I posted my 2023 and 2022 lists.