There’s no subject too big or little for rock books these days. Memoirs by and bios of superstars and obscure cult figures; overviews of entire genres; a 920-page reference book that covers just one country and one decade; coffee table photo productions; even a bit of fiction – they’re all here. It’s a more fertile ground for me these days than rock reissues or film documentaries, and more time-consuming, since you can listen to or watch records and movies in an hour or two, but most books take up more time than that. Sometimes considerably more time, when you get in the 500-1000 page realm, as a few of these do.

It’s so hard to keep up that it’s impossible for me to get to (or even become aware of) everything I’d like by the end of the calendar year in which they’re published. So, as usual, this adds some 2018 titles to the end of the main 2019 list. More than usual, actually, since there are almost ten of them. No one’s griped about my doing this in years past, but if this is thought to be cheating somehow, my feeling is it’s better to review these books at some point—and really, 2018 wasn’t so long ago—than not at all. I’m sure there will be some 2019 books supplementing my 2020 list, impurifying my legacy even more.

It’s a close race, as usual, between the #1 and #2 picks, whose order could easily be reversed. If a tiebreaker’s needed, I usually go with the subject that hasn’t been as fully documented elsewhere, as I did for this list.

1. That’s the Bag I’m In: The Life, Music and Mystery of Fred Neil, by Peter Lee Neff (Blue Ceiling). The subtitle isn’t hype: more mystery surrounds Fred Neil’s life than that of almost any other significant cult figure, from folk-rock or ‘60s rock or otherwise. It seems like making a 300-page biography would be an impossible task given the absence of crucial hard information about the singer-songwriter, who only gave one print interview (and that a not very in-depth one). Considering the obstacles, Neff did a heroic job of uncovering a lot of previously undocumented details, including Neil’s real name (Fred Morlock), his upbringing (wayward but not quite as volatile as some have speculated), and his time as a Brill Building songwriter and sporadic recording artist in New York in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. His mid-‘60s prime—when he recorded folk-rock classics like “Everybody’s Talkin’,” “The Other Side of This Life,” and “The Dolphins”— properly gets the bulkiest coverage, with plenty of stories from associates and his many (often more famous) admirers. Plenty of hitherto unknown background comes to light, including the lowdown on several unreleased albums’ worth of live and studio recordings; session details for some of his best work; plans, unrealized, for him to play at Woodstock and, even more obscurely, Altamont; and a good number of rare and unpublished photos of the notoriously reclusive Neil.

Of more importance, the writing is of a very high standard—certainly way higher than it is for most self-published books, and many books about cult figures. Neff admires Neil’s work with fervor, but looks at his life with commendable objectivity. He points out not only his oft-overlooked generosity, but also his problems with drugs, women, and the music business (which seemed to have taken more advantage of him than it did of most comparable figures). One surprise is speculation, backed up by some evidence, that Neil might have been dyslexic to the point where literacy was a true problem, explaining to some degree his struggles with contractual and financial matters. His post-1970 activities, or perhaps more accurately inactivity, are also examined, and don’t take up more space than necessary, considering his musical output was sporadic and eventually dwindled to nothing.

Even with the book’s considerable length, much mystery still does remain about Neil. Particularly, why he wrote so little after his classic 1966 Fred Neil album; why he performed so little in the wake of his best work; and why he seemed reclusive not just to the point of zealous privacy, but near-mania. Those mysteries probably can’t be unraveled any more than Neff did here, even though he interviewed many people who knew Neil. One gets the sense that Neil wouldn’t have had much or anything to say even if he’d been cornered into a retrospective interview. But as much as fans might

hunger for more detail on the deep-voiced, enigmatic songwriter—a big influence, as often testified in these pages, on a great many singer-songwriters who became more famous (including David Crosby, Stephen Stills, occasional collaborator John Sebastian, Joni Mitchell, Barry McGuire, Denny Doherty, Jerry Jeff Walker, Tim Buckley, and others)—there probably won’t be any more than you’ll find here.

2. Guitar King: Michael Bloomfield’s Life in the Blues, by David Dann (University of Texas Press). There have been some massive over-600-page rock bios in recent years. But they’ve usually been for pretty big names like the Beatles, the Byrds, and Ray Davies, and not for somewhat lesser known, if still very significant, artists from the same era. Michael Bloomfield’s one such figure, and this is one such book, running to about 750 pages. That might scare off some potential readers, but remarkably, there’s very little filler in a volume that’s both extremely detailed and a very enjoyable read from beginning to end. With deep research that extends to quite a few unreleased live and studio tapes, Dann covers the blues-rock guitarist’s journey from Chicago blues through stardom, or something close to it, with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the Electric Flag, and collaborations with Al Kooper.

Bloomfield’s descent after the ‘60s was a long and painful one, but it’s still interesting to read about—more interesting, I dare say, than the erratic records he fitfully released during his last decade or so.

His problems with drugs, insomnia, and women are not ignored, and in fact are discussed pretty extensively, though not with sensationalism. The tragedy of his life isn’t only how he couldn’t maintain the artistic highs of the likes of the East-West Butterfield album and his work on Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited. It’s also how he lost interest and motivation in maintaining significant creative musical output in the 1970s, in part because of his unwillingness to make the usual accommodations to the music business that are necessary to keep a career going.

The prose occasionally flirts with getting too in-depth. Readers probably don’t need to know a play-by-play of the Monterey Pop Festival lineup (everyone who played, not just the Electric Flag), for example. Bloomfield’s albums and live tapes are dissected song-by-song, which can be too exhaustive for the mediocre ones (and the author agrees that some were mediocre or flawed). But the quality of the writing’s very good, and some little-discussed works that deserve greater recognition get full due—I’m not sure there’s this much coverage of the Electric Flag’s The Trip soundtrack anywhere else, to take one instance. This is worth the considerable investment of time you’ll need to digest the whole tome, and a significant addition to blues-rock scholarship.

3. Outside the Gates of Eden, by Lewis Shiner (Subterranean Press). This is an arguable inclusion in a best-of list for music books. Not because of its quality (which is very high), but because it’s not exactly a music book, and not even non-fiction. Like some other novels and short stories by Lewis Shiner, however, it draws heavily on rock music. And unlike most authors that try to use rock in fiction, Shiner really does know a lot about rock history, and how rock musicians speak and act.

At first his latest and by far most ambitious book, Outside the Gates of Eden, seems to set the stage for another story set in the rock world. Hero (and sometimes anti-hero) Cole works his way up through ‘60s Texas teen garage bands to the Fillmore and the verge of rock stardom before seeming to throw it all away. The journey takes him through the college frat circuit, the San Francisco psychedelic scene, and Woodstock before it goes off course.

But Outside the Gates of Eden is much more than a tale—albeit much more convincing and realistic than almost any other—of a fictional rock almost-star. Its 870 pages take in many other characters and many other milieus of Cole’s generation. These journey from back-to-the-land communes and the snobbish New York art world to abusive police, broken families, and a struggle for integrity and justice that leads Cole and his best buddy into dangerous crime-ridden Mexican climes. And it somehow culminates fifty years after its mid-’60s launch with a high-stakes poker game in Mexico, where the stakes are higher than mere money, or even a mere life or two.

Cole’s struggle to regain a foothold in the music business might be the strongest thread of the book’s latter sections, but it’s hardly the only one. There are also struggles between the political and lifestyle philosophies of different generations, especially with Cole and his estranged father. There’s a delicate balance of family and romantic relationships, always threatening to fall off a high-wire as the characters change, sometimes radically, and at different rates. There are insider takes, unfortunately pretty accurate as far as this music journalist can tell, of the ruthlessness of the music industry.

Not least, although saved mostly for the last, there are the main characters’ quests—as they grow from middle age into senior citizens—to help do their part for environmental and social sustainability in the time they have left. It’s not only an urgent attempt to hang on to the idealism they’d first cultivated in the ‘60s; by the time of the book’s conclusion near 2016, it’s become an absolute necessity. It’s not just the story of a generation, but of an uncertain future, even as it gets ready for the final phase of its life.Outside the Gates of Eden is an epic, both in scale and sheer length.

It’s a tribute to Shiner’s strength as a writer, however, that it’s a riveting read that never sags. Besides taking on very big questions, from the value of capitalism to the sacrifices one makes both for art and the planet, it’s just plain entertaining. And if you are a rock fan, this might stand out, as it does to me, as one of the few works of fiction with strong rock elements that ring, as I wrote in a back cover blurb, “with journalistic authenticity and painstakingly accurate detail.”

Which leads into a disclaimer: I did write one of the back cover blurbs for Outside the Gates of Eden. I’m also prominently thanked in the Author’s Note, as I helped show Shiner around San Francisco (particularly Haight-Ashbury) one weekend as he researched some of that painstaking detail. I also read a draft and gave him some general notes/feedback, including clarifications about the kind of rock history details he wants to make sure are right, whether it’s when something happened at the Jefferson Airplane house, or who exactly was in the Yardbirds at a certain San Francisco show.

But whether or not I’d become friends with Lewis, I would have put Outside the Gates of Eden high on this list. Elsewhere on this blog, you can read my interview with him about the book shortly after it was published in spring 2019.

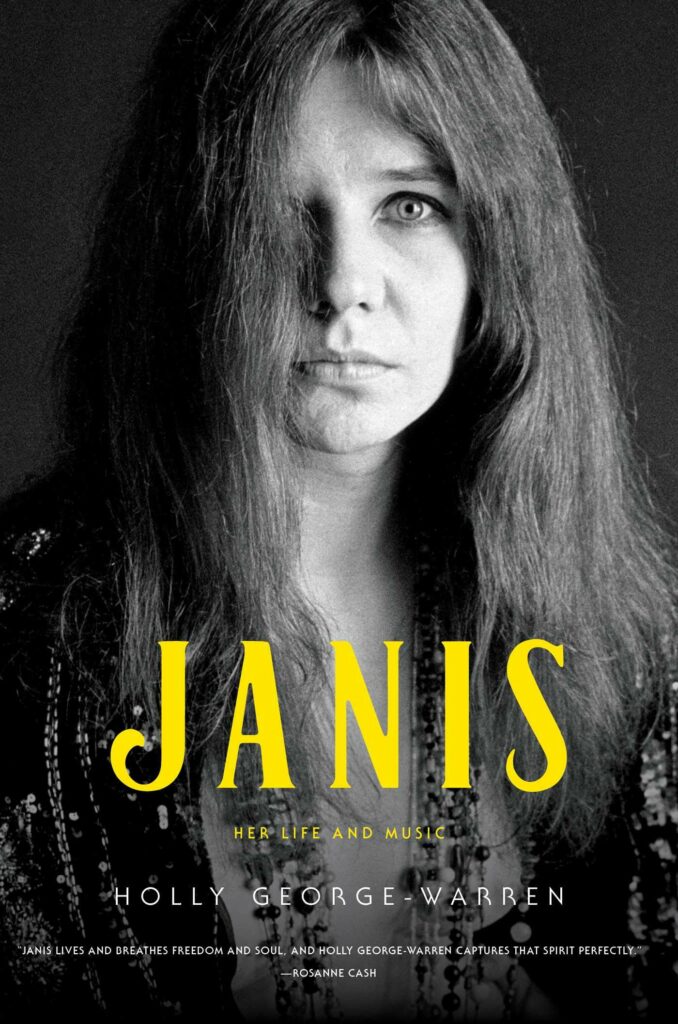

4. Janis: Her Life and Music, by Holly George-Warren (Simon & Schuster). For all her fame, there was only one good and thorough Janis Joplin biography, Alice Echols’s Scars of Sweet Paradise, before this one. While both are worth reading and there’s inevitable overlap between the two, I’d give this the edge since, as the title indicates, this pays some more attention to Joplin’s music. It doesn’t bypass her colorful personal life, but too much Joplin literature emphasizes the sensationalistic aspects of her career (and there were many), and/or her status as a cultural/feminist icon. Those features are important and noteworthy, but her music is what’s most important.

It’s covered in depth here, with lots of description of both released and unreleased recordings, as well as first-hand interviews with associates and research into archives and personal letters. While there’s lots of detail, it’s also a fast and absorbing read. Her post-Big Brother output might get less space than the two-and-a-half years with Big Brother, but at a little more than 300 pages, it doesn’t skimp on anything crucial. Her sometimes murky activities, musical and otherwise, in the first half of the 1960s are tracked with as much diligence as they ever have. Two good inserts with dozens of photos too, some uncommon.

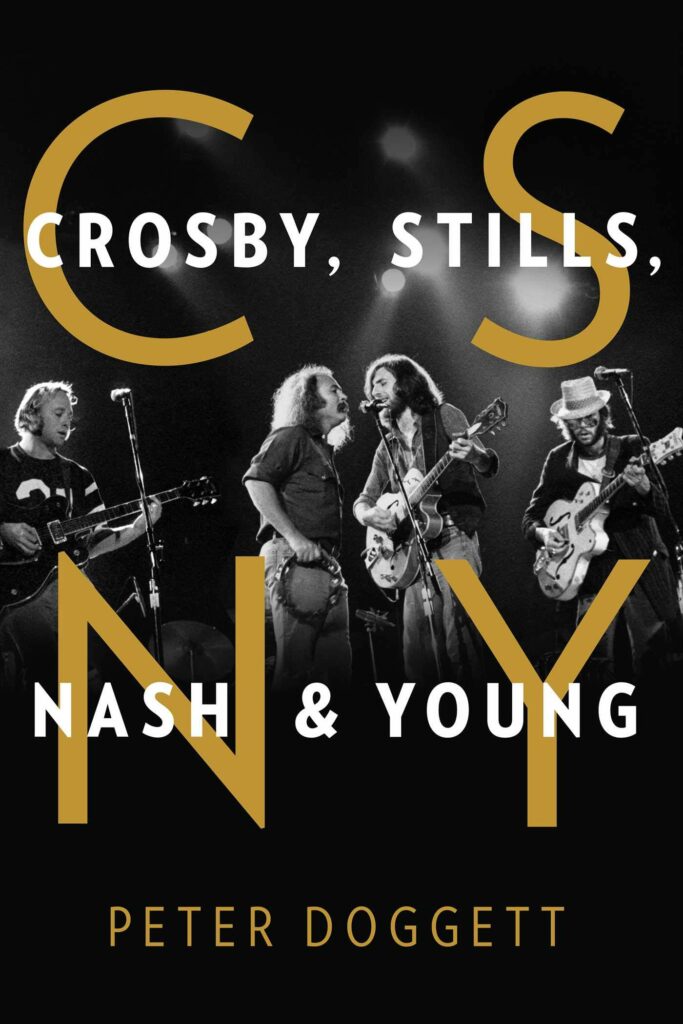

5. CSNY: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, by Peter Doggett (2019, Atria). For all their massive fame, this is the first really good book about Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Although their prime only lasted for the year and a half after they formed (and Neil Young was only aboard for the final half or so of that period), there’s more than enough to fill 330 pages, even if it rightly focuses almost exclusively on that era. Doggett dug deep into their unofficial studio and live archives, and if for nothing else, his work’s valuable for sorting out the mass of confusing and sometimes contradictory accounts of such basic elements as where and when they formed. The book also details not just the two studio albums CSN/CSNY did in 1969 and 1970, but also the extensive tendrils of other demos, live recordings, and outtakes they cut at the time, sometimes solo or without all three or four present. In addition, Doggett draws on interviews he’s done with CSN and some of their associates over the course of many years, as well as interviews they gave for others, some quite obscure.

As just a few examples of the relatively little-covered territory examined at length, there are accounts of their numerous failed (and sometimes ludicrously over-ambitious) film projects, or how exactly a non-Woodstock performance of “Sea of Madness” ended up on the Woodstock soundtrack. But the abundance of interesting trivia doesn’t overwhelm the main story, which focuses on how such talented but egotistic folk-rock performers managed to get together in the first place, and the fragile balance that made unity impossible to maintain, even as superstardom briefly reached near-Beatles levels. Wisely, it doesn’t stretch out the tale beyond its primary points of interest, taking care of their post-1974 tour reunion projects (many aborted) in just twenty pages.

Minor criticism: the primary sources for the many quotes are listed only once “to avoid repetition.” Some of us do care where all of these quotes appeared. If the aim was to save a lot of paper, in this day and age, it’s not too hard to post them online and include the link in the footnotes.

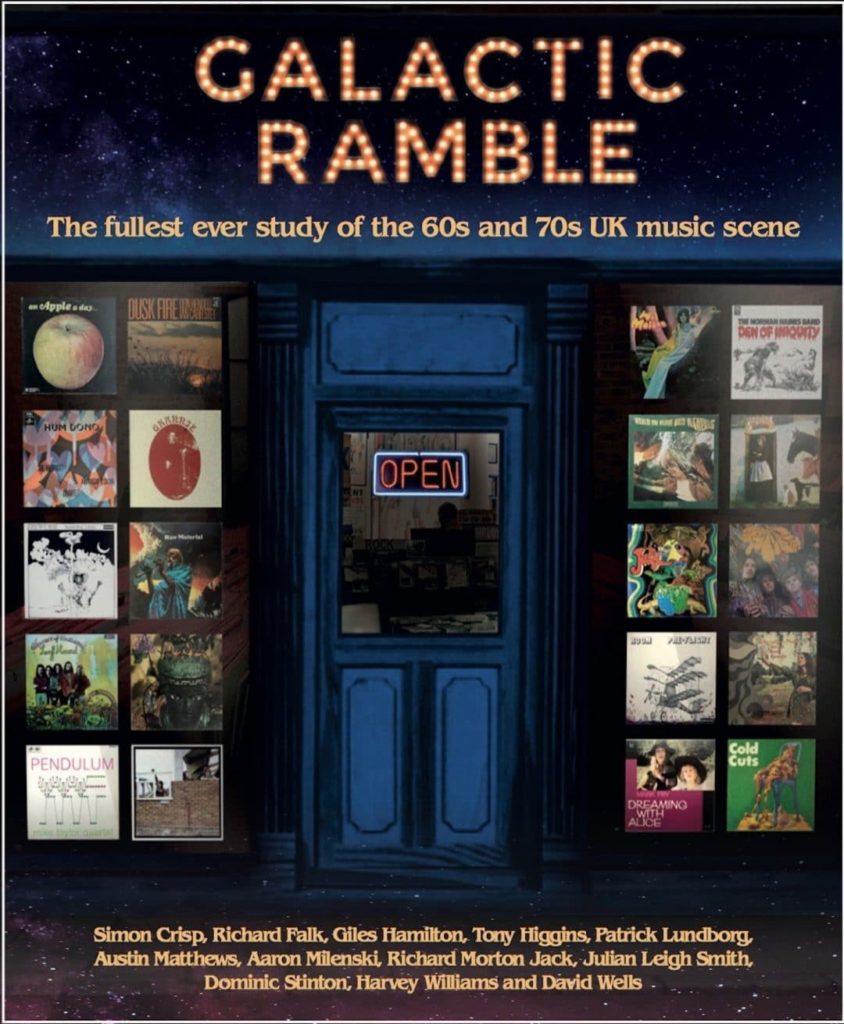

6. Galactic Ramble, edited by Richard Morton Jack (self-published; galacticramble.co.uk). When its first edition came out about ten years ago, Galactic Ramble seemed an unimaginably huge reference work for British music’s beat-to-prog prime. Its 530 pages combined vintage and newly written reviews for a vast range of British Isles LPs from the mid-‘60s to the mid-‘70s. Could a new edition even find that much more to document, let alone count as an essential purchase for serious fans and collectors?

The answer’s an emphatic yes. With more than 900 near-coffee-table-sized pages of three-column print and more than a million words, it’s not just radically expanded. It’s one of the biggest books of any sort you’re likely to own. Crucially, it’s not just or primarily lists of discographies, though the most essential release/label/catalog # info’s here. Under the guidance of Flashback magazine editor Richard Morton Jack, a team of a dozen or so expert writers/collectors review virtually all of the entries in descriptive depth, alongside extensive excerpts of reviews from the UK press at the time the LPs were issued.

Alongside entries for familiar stars and classics are thousands of reviews of albums seldom listed (let alone critiqued) in standard reference books, from major label flops to obscure indies and private pressings. There can’t be many other books that review fourteen Peter & Gordon LPs, to take one example. Although rock’s the main focus, quite a bit of jazz, folk, Christian rock, library music, and even school project records are also covered.

It’s also astounding how many vintage reviews Jack’s uncovered, and not just for the expected popular records. There are nine, for instance, of Peter Bardens’s solo debut, and eleven (!) for Trader Horne’s sole full-length. They’re sourced not just from the usual weekly papers like Melody Maker, NME, and Sounds, but from literally dozens of others as well, ranging from underground mags like IT and Oz to forgotten music business rags like Record Retailer. There’s even a Penthouse review of Bert Jansch’s debut, to cite one especially deep dive.

While the vintage reviews are of considerable value for giving us a sense of how these records (famous and otherwise) were received at the time, they’re also often more blandly positive than you’d expect, as if they have an eye toward trying to sell as well as judge product. It’s also a hoot to read some misfires on LPs now accepted as core classics. NME thought Van Morrison sounded “for all the world like Jose Feliciano’s stand-in” on Astral Weeks, putting the boot in (or deeper down its mouth) by adding, “Morrison can’t better or equal Feliciano’s distinctive style.” The same publication felt Nick Drake’s “voice reminds me very much of Peter Sarstedt, but his songs lack Sarstedt’s penetration and arresting quality.”

Written decades later, the retrospective reviews commissioned for this volume are not only usually substantially lengthier and more detailed, but also more knowledgeable and critically acute in their assessments. They’re also peppered with interesting trivia and clarifications, though not at the expense of highly readable, entertaining, and (usually) concise overviews of the music. Who would have thought the rare CBS double LP sampler Rock Buster, a 1970 release with a young Arnold Schwarzenegger on the cover, includes a completely different take of Trees’ “Polly on the Shore”?

Sometimes the fresh reviews might overreach in their cross-references to records that might draw a blank even with huge collectors. Patchy Fogg’s Today’s Weather, itself a pretty unknown item, “was released on the same label as Oberon, but is more comparable to bands like Galley or Gallery.” Sometimes the bolder assertions are almost spoiling for a fight, as when a Searchers review asks, “even as a singles band they didn’t leave us much to remember. Beyond ‘Needles and Pins,’ how many of their hits can you name?” And there’s revisionism that can cross the line to extremism, a review of Jesus Christ Superstar concluding, “Has there ever been a better rock opera? Certainly not Tommy.” Ack!

And for all its comprehensiveness, Galactic Ramble actually does miss a few titles here and there, or omit some artists some collectors would have liked to make the cut, like Irish folkies the Johnstons and Ronnie Lane post-Faces. It’s selective in US-only releases (no Got Live If You Want It! in the Stones section, for instance), and there’s little reggae. On the other hand, plenty of non-UK albums by British Isles artists (usually with material partially or wholly unique to the releases) do make the cut, including some variants even fans of the artists might be unaware of, as well as odd titles by British acts issued in the States but not at home, like Dana Gillespie’s well-regarded Foolish Seasons.

Other big pluses include reproductions of literally thousands of vintage LP ads with graphics ranging from the striking to absurd, some of them with text that’s quite interesting in and of itself, like Pete Townshend’s extensive comments on behalf of King Crimson’s debut; a couple inserts with full-color reproductions of dozens of particularly rare or peculiar-looking LP covers; an extensive introduction by producer David Hitchcock with insider insights into all facets of the UK record industry at the time; and numerous top ten lists that get into some real esoteric yet fascinating territory, a la “ten sleeves that rarely show up in top shape” and “ten LPs with cringe-making spoken sections.”

Vernon Joynson’s massive discographies covering the same era in various continents have their value, of course, and the late Patrick Lundborg’s The Acid Archives goes deep into American obscurities from the same era. Morton Jack’s own Endless Trip applies much the same approach as Galactic Ramble to North American releases. Galactic Ramble, however, is the best rock reference book to date for documenting a specific era with such detail and blend of enjoyable criticism with hard information. It’s expensive (£100, with shipping running to £35 if you’re not in the UK or EU), but essential for serious rock scholars, and won’t be around forever, as this hardback edition’s limited to 500 copies. (This review previously appeared in Ugly Things. You can read my interview with Morton Jack about the book here.)

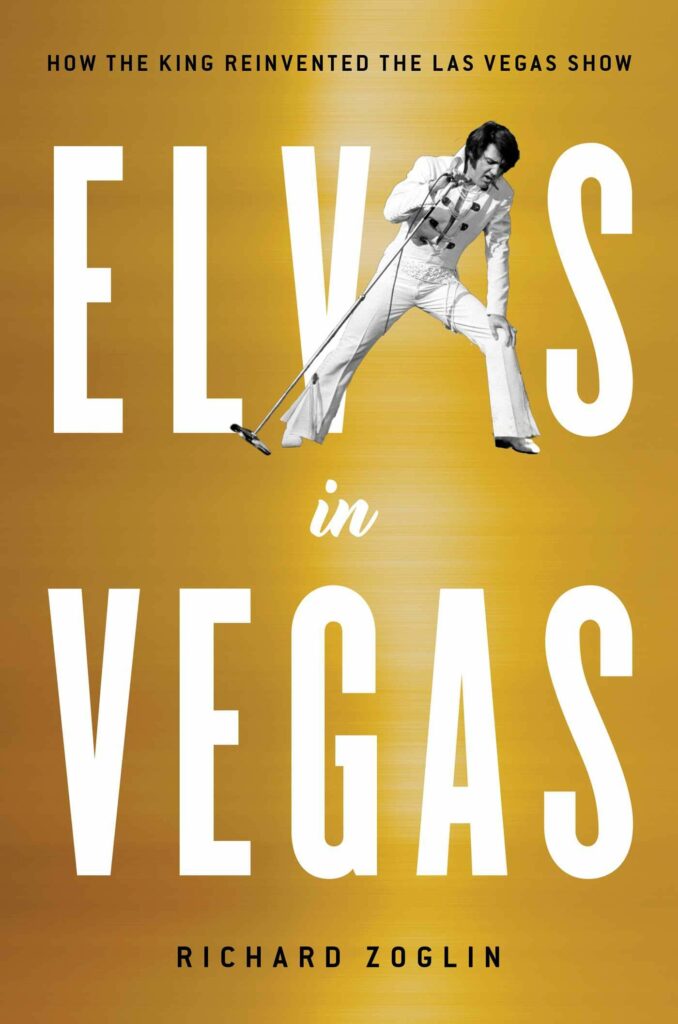

7. Elvis in Vegas, by Richard Zoglin (Simon & Schuster). Title to the contrary, this isn’t totally a book about Elvis Presley’s stints in Las Vegas, though it takes up a good chunk of the text. It’s about as much a book about how Las Vegas entertainment took shape in the mid-twentieth century, and how Presley’s shows, specifically those in 1969 and 1970, changed the way it was presented. That’s not such a big deal, since the book’s very good, even if it might disappoint some Elvis fans expecting something different. In fact, more than half the book’s over with before it gets to his 1969 comeback shows, first dealing with how Las Vegas became a gambling capital, and how shows at the casinos and hotels evolved from the 1940s onward. Even if you’re not especially a fan of the kind of acts that blossomed there, like the Rat Pack, this is pretty interesting, laying out how the musicians and comedians were primarily there as loss leaders for the real money to be made from gamblers. But over decades, the kind of entertainment accompanying that business took on a life and character of its own, with glitz, schlock, and a haven for pop singers and standup comedians whose work was drying up as popular tastes shifted.

Presley fans, fear not: there’s a lot about Elvis too. Not just his comeback shows, but also his unsuccessful first series of Vegas shows in 1956, and his periodic stops in the town for R&R over the next ten years, as well as the film Viva Las Vegas. The buildup to his decision to return to performing after his 1968 TV special and artistic renaissance on record is also covered, and naturally the first series of shows in summer 1969 is extensively documented. The subsequent Las Vegas residencies are examined in steadily diminishing detail, which is okay, since they became less interesting as time went on. Zoglin also looks at how Presley’s Las Vegas shows both changed the city’s entertainment and how Presley’s concerts were influenced (if not enormously so) by the new era, including the stage act of another singer who made Vegas a second home, Tom Jones. The book also supplies the answer to an interesting trivia question: the only artist to play both Woodstock and Vegas in 1969. (Answer: Blood, Sweat & Tears.)

8. Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life of Robert Johnson, by Bruce Conforth & Gayle Dean Wardlow (Chicago Review Press). As Robert Johnson’s life has been hazily documented in the absence of much hard evidence as to what happened when, it’s something of a miracle that a fairly lengthy biography has been constructed of the bluesman. Much about him remains and will likely remain mysterious. But this still pieces together many of the basics, drawing on painstaking grunt research and interviews with seemingly everyone who could have been found who knew or knew something about the man. Obviously many of those interviews took place decades ago, and it must have taken a long time for all or at least some of these pieces to fit together. Now we have a reasonably comprehensive account of Johnson’s rambles, music, and recordings, including his death (from poisoning, although the drink that did it seemed intended just to make him ill) at the age of 27 in 1938.

Occasionally there’s an overabundance of contextual detail (particularly in early sections detailing which relatives lived where) that could have been condensed. Yet it’s also for the most part very readable, avoiding the stilted academic prose some scholarly blues works fall into, and also steering clear of too much conjecture to fill in the gaps. The two recording sessions that yielded all of his recordings are discussed in depth, including how he got briefly jailed the night before the first day of these, and why it’s unlikely he recorded facing a wall (as an illustration for an early Johnson compilation intimated). John Hammond’s too-late search for Johnson to appear at a New York concert is noted, and it’s briefly relayed how he did try out an early electric guitar during a New York visit, but preferred to stick with an acoustic, though he liked the electric instrument’s volume.

There isn’t often much humor in books like this, but here’s a funny comment from the daughter of a guitarist the young Johnson learned from, Ike Zimmerman. “There wasn’t no crossroads,” states Loretha Zimmerman. “They went ‘cross the road.’” More soberly, Johnny Shines had this to say about Johnson and women: “Did Robert really love? Yes, like a hobo loves a train—off one and on another.”

9. Dick Waterman: A Life in Blues, by Tammy L. Turner (University of Mississippi). Dick Waterman was a booking agent, promoter, and manager for many blues artists during the 1960s blues revival. He continued to work with many of them after that decade, as well as managing Bonnie Raitt for many years at the start of her career. Waterman didn’t want to write his own memoir, but this biography almost reads like one, so extensively is he quoted. That works fine, since he’s a good storyteller, not just about the music of the artists he handled, but also about the ups and downs of the business end that most fans don’t see. That includes shepherding elderly bluesmen who haven’t played professionally for decades from gig to gig, trying to get back royalties for musicians who’ve seen little money, and even getting beaten up trying to defend a bartender at a club where his clients regularly played.

The list of artists with whom he worked closely, and tells quite a few stories about, is extremely impressive. Among them are Son House, Skip James, Mississippi John Hurt, Junior Wells, Buddy Guy (it’s noted here that Apple Records expressed some interest in signing him), Fred McDowell, Maria Muldaur, and of course Raitt (with whom he had a romantic relationship for years, though her ascendance to superstardom happened after they parted ways. Also rather amazing, however, are the number of other interesting figures with whom he had significant interactions, not all of them from the blues world. Again, a partial list: the Rolling Stones, Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, B.B. King, Eric Clapton, Dion, and Taj Mahal.

There are stories here and there that could have been cut or shortened, but most are very interesting, spanning the gamut from funny to tragic. Although it’s not a big part of the narrative, there’s also a sense of how difficult it was for Waterman to survive in this profession, falling into the outskirts of poverty not just as a youth, but throughout his career. Also included are some of the many photos he took in the ‘60s of the legends with whom he interacted.

10. My Week Beats Your Year: Encounters with Lou Reed, compiled by Michael Heath and edited by Pat Thomas (Hat & Beard Press). Lou Reed was notorious for giving acerbic interviews and his hostility toward journalists. There’s certainly some of that in this collection of three dozen interviews spanning 1971-2007, many of them never reprinted before (or, in the case of a few radio interviews and press conferences, never printed anywhere before, to my knowledge). Yet he’s also, and not infrequently, pretty informative and straightforward, depending on whether he seems to respect and trust the interviewer. Anyone with an interest in Reed (and the Velvet Underground, who do come up in conversation fairly often although he’d left the band in 1970) will find a lot of comments with worthwhile perspectives and uncommon nuggets of trivia and recollections. Even the pieces in which he’s polite and friendly are usually spiced with some sarcastic and cutting remarks, some of them simply rude, but some also pretty funny and witty.

The sources range from high-circulation mags (Rolling Stone, Creem, Circus, MOJO, Melody Maker) to unlikely mainstream publications (Hit Parader, Hits), big daily papers, Trouser Press, and the BBC to outlets where many wouldn’t think to look. Bob Reitman’s 1976 interview for the Milwaukee Bugle-American, for instance, is one of the better lengthy chats Reed gave (and virtually devoid of any rancorous attitude or game-playing). There’s even a 2003 interview with Kung-Fu magazine. Some of the writers were celebrities in their own right, including Lenny Kaye, Lance Loud, singer-songwriter Elliott Murphy, and, of course, Lester Bangs (though just one of his Reed articles, from the non-obvious source of Let It Rock, is here). Besides presenting the text of the original interviews, the original pages and covers are often also reproduced, though the type in those is so small you’ll be glad all of the text is also presented in readable size in the format used for most of the pages. It’s a welcome addition to the Lou Reed library, and you can read more about it in my interview with editor Pat Thomas.

11. Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young: The Wild, Definitive Saga of Rock’s Greatest Supergroup, by David Browne (Da Capo). It’s true: two very similarly titled biographies of CSNY came out at almost exactly the same time (the one by Peter Doggett is reviewed higher up the list). That must have delighted the authors and publishers no end. But readers basically win, since both are worth reading, even if I prefer Doggett’s. The main reason? Although the writing in both volumes is good, as noted in my rundown of Doggett’s, he focuses mostly on their brief late-‘60s/early-‘70s prime. Browne’s covers the whole, often painfully drawn out half century, including the many solo and side projects. In fact, about three-fourths of it is post-4 Way Street, which makes for a mighty long, slow (and sometimes steep) decline in musical value, at least in terms of CSN if not Y.

Still, Browne interviewed more than a hundred people, including Crosby and Nash (but not Stills and Young, who did not make themselves available). And though the sporadic actual post-‘70s reunions of the quartet (and to an only slightly lesser degree the CSN trio) were both disappointing and frustrating, their tumultuous personal lives make for pretty interesting reading, if in kind of an elongated train wreck way. Browne is overly generous in his assessment of much of their work (post-1970 CSN/CSNY and otherwise), but doesn’t hesitate to discuss the flaws in their weaker efforts.

Here’s something that still escapes me, however. In some interviews, and in the recent Remember My Name documentary, Crosby emphasizes his need to keep touring at an advanced age and precarious health just to support himself. According to the figures in this book, however, numerous post-‘80s CSN/Y tours have grossed quite a few millions of dollars. Could his financial struggles just possibly have something to do with living beyond his means, or at least considerable monetary mismanagement?

12. At the Birth of Bowie: Life with the Man Who Became a Legend, by Phil Lancaster (John Blake). Phil Lancaster was drummer in the Lower Third, the group that backed a young David Bowie for about eight months from around mid-1965 to early 1966. As their sole officially released output on disc amounted to two low-selling singles, it’s not a period of his development that’s received too much attention. Still, this recollection of that fairly brief period is a pretty good read for Bowie fans, and despite its 300-page length a pretty quick one, owing in part to its large print. Even so it’s a bit puffed up around the edges with some obvious asides and observations, but for the most part Lancaster sticks to the story, recounting Bowie’s stint with the Lower Third with as much detail as he can manage. Not only are their sessions (few as they were) with hit producers Shel Talmy and Tony Hatch pretty fully sketched out, but Lancaster also lists as much of their repertoire as he can remember, including some unreleased demos and unlikely covers, like “Chim Chim Cher-ee” (from Mary Poppins). There are also notes about their passing encounters with big British Invasion stars like the Who, Small Faces, the Pretty Things, and Ray Davies.

Bowie (still billed as Davy Jones when the first of the two singles appeared) really hadn’t found a distinctive style at this point, borne out by his first 45 with the Lower Third, “You’ve Got a Habit of Leaving,” which owed a great deal to the early Who. Lancaster was a huge Who fan, and remembers the Lower Third playing with nosebleed volume at their live shows, though this largely was not reflected by their meager recorded output. They did cut a version of Bowie’s first outstanding song, “London Boys,” with Hatch, but as Lancaster relates in one of the most interesting sections, this was apparently withheld from release due to Pye Records’ uneasiness over its reference to pill-taking. Lower Third manager Ralph Horton helped split the act by focusing on Bowie and isolating the backing musicians, leading to their departure at an early ’66 gig when they demanded to be paid or not play at all. Despite the bitter ending, Lancaster looks back at both Bowie and the era with affection. Much of the book does capture the excitement of being on the mid-‘60s British rock circuit, even for groups like the Lower Third that were trailing the leaders of the pack.

13. Face It, by Debbie Harry (Dey St.). Harry’s memoir is largely entertaining and informative, though it falls prey to a few of the common flaws of rock star autobiographies. Chatty, candid, and sometimes rambling, it does largely stick to her long path from singing backup in forgettable late-‘60s group the Wind in the Willows, waitressing, Playboy-bunnying, and generally boho-ing until Blondie got off the ground in the mid-1970s. Blondie fans who’d like more of a song-by-song rundown of their best albums might be disappointed, but Harry discusses their musical evolution and personnel changes/contributions quite a bit, as well as the general milieu of the CBGBs scene. There are also some brutal hardships in the days leading up to Blondie, including a sociopath stalker and, even more grimly, a robbery and rape in the apartment she shared with boyfriend and Blondie co-founder Chris Stein. Sour management deals also led to, unbelievably, her and Stein going broke around the time the band broke up, which was also when Stein almost died from a rare and prolonged illness.

Harry relays this with much less bitterness than most celebrities in her position, which is one of the book’s strengths. Not as strong are the detours into some extramusical subjects that aren’t of such great interest, at least to me, like some of her fashion choices and her passion for pro wrestling. Like many a memoir, the final sections are less interesting as Blondie’s music becomes less vital following their reunion, Harry filling out the text with recollections of her numerous movie roles. The abundance of portraits of Harry by her fans used in the illustrations (which also include numerous good photos) are unnecessary, but not so extensive that they interfere with the enjoyment of a fairly solid effort in the rock memoir sweepstakes.

14. Fried & Justified, by Mick Houghton (Faber & Faber). Starting his career as a music journalist, Houghton became a publicist of some note in the UK from the late 1970s to the late 1990s. He worked with some of the era’s most successful or at least renowned alternative rock acts, including Julian Cope, Echo & the Bunnymen, the Jesus & Mary Chain, the Undertones, KLF, Sonic Youth, the Wedding Present, and Felt. His memoir of those times would rate higher on this list if I was a bigger fan of those artists, and the era. But it’s still an interesting look at some of the inside action from both the mainstream/major label and indie/underground sides of the new wave/post-punk scenes.

To hear Houghton tell it, you might think a publicist’s job was more to stay out of the way and let the clients have their way than to push their product hard, though I suspect he did more grunt work than he lets on. His job at times went beyond the stereotype of sending out press releases and hounding writers for stories, whether it was taking Sun Ra shopping in London or leaking KLF’s plans to throw buckets of sheep’s blood over the audience at an industry awards show to tabloids (to help ensure the event didn’t happen). Some of the stories are funny, some are depressing, but most illuminate the zany capricious ways of the period’s music business and its stars, or semi-stars. Even his more successful charges sometimes seemed so ill-suited for the spotlight that it’s not so much a question of why they didn’t get bigger, but how they got as far as they did. People like Houghton probably have more to do with it than they get credit for, though he declines to take much in this humorously deadpan account.

15. A Voice of the Warm: The Life of Rod McKuen, by Barry Alfonso (Backbeat). For all McKuen’s massive book sales as a poet and lengthy discography as a singer-songwriter, this is the first biography of the man. I’m not a McKuen fan, but as he was a significant part of the era of musical history in which I’m most interested, I was reasonably interested to find out more about his life. This biography delivers pretty well on that account, with a highly readable and critically astute survey of his personal and professional life. Understandably, the author’s evaluations are more generous than mine.

But Alfonso take a balanced view of McKuen’s strengths and weaknesses, and how the artist’s sentimental romanticism was leavened by some vulnerable loneliness, eroticism, and even some tawdry bits here and there. His personal life was more troubled than one might assume, with family abuse in his early years and a sexual identity he largely hid from the public eye. As the author acknowledges, it’s difficult to piece together his life, particularly but not exclusively his pre-fame years, with total accuracy. In part that was due to his reluctance to divulge full personal details, and in part that was due to the sometimes dubious or untrustworthy memories he did make public. This book diligently traces whatever trails it can and notes the tales that should not be taken as gospel, or did not to surviving evidence ever happen.

There’s probably lots more that could be said about his records (there were many) and writings, but given his work’s unevenness, Alfonso wisely emphasizes McKuen’s most essential and interesting efforts. As a consequence it’s not a terribly long volume, tallying around 200 pages. But it probably didn’t have to be longer, which would have risked delving into the mundane parts of his oeuvre. A fuller story would have also risked losing the interest of more general readers like me, who’ll appreciate the book’s concise overview of this popular yet oft-scorned figure.

16. Henry Cow: The World Is a Problem, by Benjamin Piekut (Duke University Press). British progressive rock group Henry Cow is one of those acts whose history I find more interesting than their music. One of the most leftist acts to make any kind of name for themselves, they combined rock, jazz, improvisation, then-cutting-edge electronic technology, and political text. The result found favor with many critics and garnered a passionate underground following, especially in Continental Europe. At the same time it was almost defiantly inaccessible to the masses, as much as Henry Cow wanted their music to make a political statement on behalf of the oppressed and working class. Appropriately, this hefty biography—almost 500 pages after the lengthy section of footnotes—is a mixture of accessible history and academic theorizing that will lose many general readers. The author even acknowledges in his lengthy sociological introduction that “die-hard fans of the band might find the most satisfaction by jumping directly to the narrative history that begins in chapter 1.”

Fortunately, the straightforward history substantially outweighs the sections focusing on rigorously delineated cultural context and musical analysis. Everyone in the band was interviewed except Lindsay Cooper (who was too ill to speak about their history), along with many associates. In common with many left-wing organizations, Henry Cow had a lot of internal struggle and debate, some of them actually common to many rock bands, like romantic relationships that got in the way, equipment and van breakdowns, disputes over musical direction, and rocky interactions with record labels. There were not many other groups, however, who hashed these out with meetings like those of political collectives, including some written statements both to the public and among themselves that could verge on political diatribes. Whether on the surface or not, the contradiction between playing adventurous music outside of the mainstream and trying to use that to rally the masses was often at the heart of these tensions.

Aside from lots of stories about Henry Cow’s genesis, mid-‘70s peak, and protracted dissolution, there’s also inside information about some other interesting topics that played a strong role in their tale. Those include fellow European prog group Slapp Happy (whose members would work and for a time merge with Henry Cow); the early days of Virgin Records, when it was for the most part an underground label, not the mainstream one it became; and the birth of Recommended Records and the Rock in Opposition movement, both of which they (and especially drummer Chris Cutler) were vital in launching. It’s also revealed that director Alejandro Jodorowsky wanted them (along with Pink Floyd and Magma) to soundtrack his adaptation of Dune, and that guitarist Fred Frith might have been considered to produce the Sex Pistols. Like Henry Cow, the book is sometimes a struggle (especially the theoretical introduction and afterword, which can be skipped by most rock fans without missing anything, or even offending the author). But it’s worth persevering with for those interested in a very different kind of rock music and history.

17. Look What They Dun! The Ultimate Guide to UK Glam Rock on TV in the ‘70s, by Peter Checksfield (self-published?). Like Checksfield’s previous, much bigger volume Channelling the Beat! The Ultimate Guide to UK ‘60s Pop on TV, this is a reference book listing TV appearances of a specific style and era. This time it’s British glam rock, listing all known TV appearances (and occasional movie ones). Helpfully, the footage known to survive is listed in boldface, making it easier to access at a time when it’s easier to do so than any other in history. Much of this is pure listings with dates, program, and songs performed, but Checksfield does knowledgeably (if often briefly) describe many of the surviving clips. The heavyweights like David Bowie, T. Rex, and Roxy Music all get chapters, but so do British acts that never made it big in the US (Slade, Hello, Mud); not-exactly-glam acts that nonetheless tapped into glam both visually and sonically (the Rolling Stones, Rod Stewart, the Kinks, the Move); and artists that never even made it particularly big anywhere (Kenny, Paul Da Vinci). Keeping the scope more manageable and the content more interesting, the end of the ‘70s is used as a cutoff point, though many of the acts continued their careers afterward (sometimes long afterward). I’d be more passionate about the book (as I was about Channeling the Beat!) if I was more of a glam fan, but it definitely has its use as a clearly formatted and thoroughly researched reference work.

18. Woodstock: 50 Years of Peace and Music, by Daniel Bukszpan (Imagine). The 50th anniversary of Woodstock spurred a flurry of books, several of which have their modest attributes. This is the best of the four reviewed here, chiefly because the author actually interviewed a lot of the performers, promoters, audience members, and crew who helped put on the event. There are small (usually two-page) chapters for each of the performers, with their set lists, and sections on the genesis of the festival, the behind-the-scenes machinations, the poster, the aftermath, the soundtrack LP, the movie, artists who were invited but didn’t play, and so on. And there are plenty of photos and illustrations. Some of the performer chapters are padded by general observations about their music, but specifics are given as to their actual sets.

19. Woodstock: Three Days That Rocked the World: 50th Anniversary Edition, edited by Mike Evans & Paul Kingsbury (Sterling). Actually this first came out ten years ago, but opportunities to capitalize on a 50th anniversary only come around once. While as an overview of the festival it’s basic, it has plenty of good photos; set lists and brief profiles/set descriptions for all of the acts; quotes from a lot of the musicians, and some of the others associated with Woodstock, as well as audience members; and a foreword by Martin Scorsese, who was operating one of the cameras for the film. Some contextual chapters about preparations for and the aftermath of the event range from interesting to superfluous. On the whole it’s better than another Woodstock retrospective issued in 2019 (50 Years: The Story of Woodstock Live, reviewed below), though both will give you a good idea of what happened, and each has material not in the other.

20. 50 Years: The Story of Woodstock Live, by Julien Bitoun (Cassell). Most of this volume’s given over to short chapters on the performance of each of the several dozen acts at Woodstock. There are set lists, brief descriptions of the actual music, some background info on the acts, and plenty of photos, though not all of them are from Woodstock itself. There are also some small pieces on the events leading up to the festival, the movie, the soundtrack albums, and the stories behind the acts that didn’t make it to the event. It’s kind of like what you imagine the liner notes to the 38-CD limited edition complete Woodstock box might be like, though this is a lot cheaper than that $800 extravaganza, especially if you take it out of the library. The writing (translated from French) isn’t that great and the critical assessments are often too generous/enthusiastic, and sometimes rather peculiar. Still, this has its use for the fairly complete documentation of what was played and when, though that’s also in other Woodstock books now.

21. Girl: An Untethered Life, by Julia Dreyer Brigden (self-published). “Girl” was the nickname of author Julia Dreyer Brigden, whose first husband was David Freiberg, of Quicksilver Messenger Service and Jefferson Starship. There’s some material about Freiberg and those bands here, but mostly this is a memoir of growing up in Marin County in the 1960s and 1970s. By the time she reached adolescence, Girl was kind of wild, running away to Mexico, marrying a local rock star ten years her senior as a teenager, and having a daughter with him not long afterward. Even well into their marriage, Girl often took off for wayward travels around the world, though she settled down into a more conventional and grounded life after quitting drugs (and, post-Freiberg, drug dealing) by the ‘80s.

This is pretty interesting and well written as memoirs of coming of age in the loose environment of the ‘60s Bay Area go, but it will disappoint those looking for inside info on the rock scene. There are a few interesting stories about the internal dynamics of Quicksilver; Dino Valenti comes off very badly, and Gary Duncan not much better, especially as regards their sexism. And there are a few observations about Paul Kantner, Grace Slick (who advised Girl about seeking help for her substance abuse problems), and David Crosby (Girl was nearly a passenger in the accident that killed Crosby’s girlfriend Christine Hinton in 1969, and was among the first to arrive at the scene of the crash). It’s more her personal tale of her rocky journey from girlhood to adulthood, distinguished from other accounts by the Bay Area setting and the circles in which she traveled. And the chronology’s shaky on some of the experiences with rock stars, though that’s only likely to picked up by the kind of rock nerds who actually remember when Crosby’s If I Could Only Remember My Name was recorded.

22. Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace & Music, by Michael Lang (Real Art Press). Fiftieth anniversaries only come around once, so Woodstock’s fiftieth occasioned several graphics-oriented coffee table books, as well as a PBS documentary and a 38-CD box set. This one, by Woodstock co-promoter Michael Lang (who with Holly George-Warren put out a conventional text memoir of the event, The Road to Woodstock, ten years ago), has less text than the others listed in this survey. Unlike those others, it doesn’t focus on the music, and in fact has relatively little about the music, concentrating instead on how the festival was created, organized, and run. So it’s less interesting, at least to me, than the other two, though the text has its points of value. More interesting are the wealth of photos, in both color and black-and-white, the majority taken by Henry Diltz. These cover the festival from many angles, from inception to aftermath, including not only star performers, but also many shots of the audience and members of the upstate New York community.

Of particular note are some rarely seen documents, like a poster for the festival at its original (canceled) location in Wallkill; the contract for Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young’s appearance (“under no circumstances are Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young to open the show”); a list of artists and their fees, including some who didn’t appear, like Iron Butterfly ($10,000) and the Moody Blues ($5000); and most especially a July 7, 1969 letter from Apple offering to present Billy Preston and James Taylor. They didn’t appear, as Lang didn’t find the unopened letter until about forty years later. The letter also offered to show a film by John Lennon and Yoko Ono, also stating “we will also present for the first time in America ‘The Plastic Ono Band,’ which actually is a series of plastic cylinders incorporated around a stereo sound system.”

23. Jim Marshall: Show Me the Picture, by Amelia Davis (Chronicle). The companion book to the documentary Show Me the Picture: The Story of Jim Marshall has many pictures by the acclaimed, usually San Francisco-based photographer. Marshall was mostly known for his work with musicians, and photos of rock, blues, jazz, soul, and country artists in the 1960s and early 1970s (most in black and white, and a few in color) dominate the volume. There are also some non-music pictures, mostly dating from the early 1960s, and often of the American poor and/or minorities. Although the text is fairly sparse, there are also memories and appreciations of Marshall from some who knew and worked with him. His legal and drug troubles, as well as frequent unruly behavior, are not ignored, though the essayists emphasize the positives of a talented but troubled man.

24. Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll, by Jayson Kerr Dobney and Craig J. Inciardi with Anthony DeCurtis, Alan di Perna, David Fricke, Holly George-Warren, and Matthew W. Hill (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). The catalogue of a 2019 exhibit of rock instruments at the MET in New York is a full-blown hardback book, with essays by seven contributors on different related topics: “Guitar Gods,” “The Rhythm Section,” “Creating a Sound,” “Creating an Image,” and Iconic Moments” are some. The text has adequate overview-type information, though as only a relatively small number of musicians (most stars) are specifically examined, there’s some repetition of both details and viewpoints.

More notable than the text, which doesn’t contain much fresh or surprising information for knowledgeable rock fans, are the numerous photos, many of which are of instruments from the exhibit. Gearheads might get more out of this than the average reader, but there are some unusual and especially historic items. Those include the 1964 Fender Stratocaster Bob Dylan played at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival; a beat-to-hell-looking Fender Esquire Jeff Beck used with the Yardbirds in the mid-1960s; and one of the Mellotrons the Rolling Stones used in their brief 1967 psychedelic period. It’s kind of expensive ($50) for what you get in the 236-page book, and some interesting instruments from the exhibition (listed in an appendix) aren’t pictured in the book, like a Telecaster Jimmy Page played with a violin bow in the Yardbirds. It adds up to something most of us should get from the library if we can, unless you’re an instrument collector or fetishist.

The following books were all published in 2018, although I didn’t read them until this year:

1. What We Did Instead of Holidays: Fairport & Its Extended Folk-Rock Family, by Clinton Heylin (Route). This isn’t solely a history of the first dozen or so years of Fairport Convention, although they’re the core around which the text revolves. This also covers the numerous spin-off acts Fairport generated, including Steeleye Span, Matthews Southern Comfort, Trader Horne, Fotheringay, the Albion Country Band, and the solo careers of Sandy Denny, Richard Thompson, and Ian Matthews. A lot of those acts (including the still-active Fairport) kept going a long time, but this book is only devoted to the era starting with Fairport’s founding in the mid-1960s, and ending with Richard and Linda Thompson’s breakup in the early 1980s.

Heylin follows a format he’s used on some of his other books, mixing his own text with many quotes from the participants, both from his own interviews and archival sources. It’s an interesting and fast-moving tale that, while documenting one of rock’s more subdued styles (British folk-rock, in which Fairport were the most important band), brings to light many tumultuous artistic and personal forces that were taking place behind the scenes or playing out in public. In his numerous books (including his biography of one of the principal figures in Fairport, Sandy Denny), Heylin can be smugly opinionated, but that’s dialed down here, and mainly reserved for barbs at CD compilations he feels could have been better assembled. Some other books, such as Heylin’s Denny biography, do go deeper into the details of specific acts like Thompson and (in the memoir Thro’ My Eyes) Matthews. But this weaves the complicated story of Fairport and its offshoots together pretty well, and is better than the best other Fairport book, Fairport By Fairport.

2. Truth, Lies & Hearsay: A Memoir of a Musical Life in and out of Rock and Roll, by John Simon (self-published). As the subtitle notes, Simon was “producer of the Band, Janis Joplin, Leonard Cohen, Simon & Garfunkel, Blood, Sweat & Tears, etc.,” though that sentence lists most of the familiar acts with whom he worked. Although his autobiography’s 332 pages, it’s a quick read, since he writes in short paragraphs and uses plenty of margins and white space. That doesn’t mean it’s not worthwhile, though it’s not major, either. He has a fairly engaging, storytelling style that runs through his experiences with all of the aforementioned acts; a few others he produced that are well known (the Cyrkle, Gordon Lightfoot, the Electric Flag, Cass Elliot, Steve Forbert); and some who aren’t well known or even often discussed by cultish fans, most of those dating from after the early 1970s.

The bulk of the book covers the late 1960s and early 1970s, when he achieved his peak successes with the Band and Big Brother & the Holding Company. Some of the tales will be familiar to knowledgeable followers of those groups, and maybe more interesting for his down-to-earth, humble perspective on his role and their records than the actual facts involved. But he does inject meaningful observations on his contributions as a producer, and indeed how the nature of a producer’s contributions can vary according to the specific project. There are also wry, cynical takes on the capricious and sometimes cruel music business. For those looking for something not covered in the usual mainstream histories, he discusses his own quirky obscure solo albums, which do have their admirers, though not legions of them.

It’s a little odd that while the first two Band LPs are examined in more detail than anything else, he doesn’t get into why he didn’t continue to work with them. Too, some fairly interesting people he produced, specifically Jackie Lomax and Bobby Charles, are only mentioned in passing. Maybe that’s a matter of him not feeling those projects have good stories behind them, rather than glossing things over. But their absence is still felt, considering some that abundant white space could have been filled. I interviewed Simon about the book here.

3. Rock Graphic Originals: Revolutions in Sonic Art from Plate to Print ’55-‘88, by Peter Golding with Barry Miles (Thames & Hudson). There have been plenty of rock poster books, and this one’s a cut above most of them, for several reasons. There are a lot of reproductions, many of them not often seen in books, and most of them (despite the wide yearspan of the subtitle) from the mid-‘60s through the early ‘70s. Unlike most such volumes, a good number of the illustrations show how the work progressed, again referencing the subtitle, from plate to print. That’s a technical process that might interest professionals and specialists more than general readers, but it’s not overdone and doesn’t take away the main stage from actual poster repros. The captions aren’t too extensive, but nonetheless are more informative than they are in similar anthologies, with basic essential details and some interesting info about how/where/why these were produced.

What’s coolest is that while San Francisco rock posters might be the largest category here (in common with a good number of other rock poster books), this also makes room for posters from different regions, and on different subjects. There’s even a psychedelic poster for a Haight-Ashbury ice cream parlor. Posters from London, Detroit, Los Angeles, and other non-Bay Area locations get some ink. So do posters for non-rock events/subjects like a Diggers happening and a legalize pot rally, and rock poster-influenced publications like underground papers and comics. Some of the San Francisco posters hold special interest, like the one for the Fillmore with a lion that was redrawn by Lee Conklin for the cover of Santana’s debut album. There’s a little too much Grateful Dead here (again in common with some other poster surveys), but most of this is novel and refreshing, even if you’ve seen a lot of these kind of graphics elsewhere.

4. Imagine John Yoko, by John Lennon & Yoko Ono with contributions from the people who were there (Grand Central Publishing). I’m not a big fan of John Lennon’s Imagine album; otherwise, I’d like this 320-page coffee table book devoted to the record more. Still, it’s a very well put together volume that has a lot of text, photos, and graphics to entertain and enlighten if your interest in Imagine is at least casual. Besides extensive memories of the sessions and comments on the songs from Lennon and (to a lesser degree) Ono, there are comments from many people who were involved in the album and its associated projects, including films and art exhibitions. That includes not only session musicians like Klaus Voormann, but also numerous engineers, personal assistants, filmmakers, and others. These are drawn from both interviews done for the book and vintage sources—all of them vintage, unfortunately and obviously, in Lennon’s case.

Visually, there’s an abundance of photos, movie stills, handwritten lyrics, and other ephemera. Most of the images are meticulously dated with locations noted—something that should be a given for books like this, but too often isn’t, especially in rock/popular culture publications. It raises hopes that more such works will be produced for classic rock albums/artists in the future, as not many succeed with both the text and visuals. John and Yoko could be vainglorious in their zealous documentation of their art and lives (something that comes through far more strongly in their Imagine film), but the book largely avoids this, for all its thoroughness. Favorite Lennon quote from these pages (about the song “Imagine”): “The World Church called me once and wanted to say, ‘Can we use the lyrics and just change it to “Imagine one religion”?’ So that showed that they didn’t understand it at all. It would defeat the whole purpose of the song; the whole idea.”

5. The Association: ‘Cherish’, by Malcolm Searles (Matador). Although they were white-hot commercially for a couple years, the Association have never gotten the critical respect of comparably successful rock bands from the mid-to-late 1960s. That’s likely part of the reason there hasn’t been a bio of the band until this one, which should satisfy anyone who wants a complete story of the pop-rock harmonizers. At nearly 450 pages, it draws on extensive first-hand interviews with original members Jules Alexander, Jim Yester, and Terry Kirkman, as well as a wealth of quotes from them and other guys in the band from many sources (all properly footnoted). Not a whole lot of people (at least relative to the millions who bought their big hits) were too curious about all their albums and flop singles, but Searles goes through them, going back to their pre-“Along Comes Mary” folk-rock-pop singles.

He also documents their beginnings in various folk combos, and uncovers some press and publicity in which the group from which they evolved (the Men) were quite possibly the first outfit referred to as a folk-rock act, even before the Byrds and Bob Dylan really popularized the term. And there are extensive quotes from quite a few reviews of the band, even way past their prime. The author’s prone to sentences that run on way too long, and perhaps the book does too, with their post-mid-‘70s descent into the nostalgia circuit (and many revolving lineups) taking up more than a hundred pages. But it’s a readable and reasonably objective account that doesn’t sugarcoat their poor recordings, though he’s clearly a big fan of their better work. Their peak wasn’t really that long (taking in five big hits between 1966-68), but fortunately the ‘60s take up the main chunk of the volume, although it won’t convince non-fanatics that they were a major group, as big as those huge hits were.

6. Phil Gernhard, Record Man, by Bill DeYoung (University Press of Florida). The term “record man” is usually used for titans of the industry known to much of the general public, like Mo Ostin of Warner Brothers or Ahmet Ertegun of Atlantic Records. But the music business is populated by many “record men” who operate somewhat under the radar of even many knowledgeable fans, notching up hits here and there without getting identified with a particular style or vision. Phil Gernhard was one of them, not so much carving a niche as latching on to an almost random-seeming series of hits in various capacities over a span of decades. As producer, publisher, A&R guy, and whatnot, he was involved in Maurice Williams & the Zodiacs’ “Stay”; the Royal Guardsmen’s “Snoopy Vs. the Red Baron” series of singles; Dion’s “Abraham, Martin & John”; and Dick Holler’s original version of “Double Shot,” before it was made it into a hit by the Swingin’ Medallions. That’s just the 1960s; after that, he played large parts in the careers of Lobo and Jim Stafford, and then for country stars the Bellamy Brothers, Tim McGraw, and Rodney Atkins.

It’s pretty doubtful anyone’s passionate about all these records and artists. The common denominator is success and sales, not a consistent aesthetic. But if you are interested in any of them, this is a quite well told tale of Gernhard’s peripatetic, troubled career, with plenty of behind-the-scenes stories about the songs and the discs. DeYoung did his research, talking to many of the musicians (not Dion, though he tried), business associates, and family members. He doesn’t inflate it into a bigger story than it deserves, getting the job done in 160 pages. If you want a few accounts of intriguing failures, some of them are here too, like a clutch of odd Florida garage rock and psychedelic singles he tried to launch. There’s something of the “throw it at the wall to see what will stick” vibe about his operations, but then, that’s often how things get done (or screwed up) in the record world. Gerhard’s career might have been a marginal one in the grand scheme of things, but the way it’s covered here still makes for worthwhile reading, if often downbeat owing to his sad personal life and sometimes seedy business practices.

7. World Domination: The Sub Pop Records Story, by Gillian Gaar (BMG, 2018). Sub Pop might be the most famous independent label, or at least semi-independent label (having sold much of the company to Warner Brothers in the mid-1990s, though retaining majority ownership), of the last few decades. This mini-book of sorts, running about 150 pages, is a no-fat overview of the label’s foundation and rise, taking the story all the way to the 2018 year of publication. Veteran Seattle-based writer Gaar was well positioned to see the label’s progress all along, and the text benefits from first-interviews with label co-founders Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman. Several other key figures in the label’s creative and administrative departments are also heard from, including producer Jack Endino and illustrator Charles Peterson.

Sub Pop’s rise to a prominent and, eventually, very commercially successful company was an improbable and chaotic one. The most interesting parts of the story are those unlikely beginnings, with the label growing out of a fanzine by Pavitt that started to include cassettes, leading to the formation of a proper record label. It often verged on collapse in its first dozen or so years, even after getting big cash infusions with the Warner deal and the boost Nirvana’s success gave to its back catalog. By late 1996 Pavitt had even left the label as the relations between the founders broke down, though those were repaired and he did come back years later to do some consulting. With stability came a more conventional (if still relatively unconventional) business atmosphere. The latter sections detailing its various ventures into music of many styles from throughout the world—not just the Northwest base for which it’s most renowned—are not as interesting, not through any fault of the author, but simply because the story became less quirky and unusual.

8. Shake Your Hips: The Excello Records Story, by Randy Fox (BMG, 2018). Nashville’s Excello Records is most known as a label that issued prime swamp blues by artists like Lightnin’ Slim, Lazy Lester, and above all Slim Harpo. Actually, the company put out a lot of records in a bunch of different styles over its lengthy history, including gospel, soul, rockabilly, and more. Their saga isn’t really so involved or monumental that it deserves a volume on the order of books that have been done on Sun or Stax. But this well done book doesn’t overextend its reach, putting the story into 170 compact pages in a spread-out palm-sized format. Its most interesting points aren’t just some stories about how much of Excello’s swamp blues (particularly Slim Harpo’s) was recorded by Jay Miller. It’s also an insight into the complex and unpredictable genesis of labels like Excello, who emerged not so much from the vision of music lovers or even a guy looking to capitalize on music trends, but as an outgrowth of Excello head Ernie Young’s interests in jukeboxes and retail/mail-order record distribution. That itself was an outgrowth of his prior experience in non-music-related businesses, like pinball machines.

Excello also had a strong tie-in with the emergence of R&B radio, particularly John Richbourg’s show on WLAC in Nashville. The practice of paying for airtime might seem like payola now, but back then, it was just considered the normal course of building a business, both from the record and radio side. Some of the descriptions of Excello’s many releases verge on lists as Fox tries to cover so much territory, but there are also some colorful stories, such as the unlikely emergence of one-hit wonder the Crescendos’ huge rock’n’roll hit “Julie” when a guest girl singer was enlisted. As is the case with virtually all significant labels, unusual connections abound, like Swamp Dogg’s involvement with the company as a producer in the early 1970s, and (unfortunately) Miller’s Reb Rebel label, which in Fox’s words specialized in “jaw-droppingly racist records.” Also covered is the affection several British bands held for Excello, Atlantic executive Ahmet Ertegun even once declaring, “I think [Mick] Jagger would have liked to be on a funky label. I think Jagger would have liked to be on Excello. We were the closest he could get to Excello and still get five million dollars.”

9. Always Look on the Bright Side of Life: A Sortabiography, by Eric Idle (Crown Archetype, 2018). Is Eric Idle’s relationship to music tenuous? Sort of; he’s much more famous as a comedian than he is as a musician. Still, he was part of the Rutles (on film if not on record), and the main force behind creating that comic satire of the Beatles. He was the most responsible for Monty Python’s frequent musical parodies, as both a singer and writer. And he was friends with quite a few rock stars, most famously George Harrison. His memoir’s a breezy and pretty witty read, spread about evenly between his ‘60s beginnings, Monty Python’s TV show and movies, his various side and solo projects, Monty Python reunions, and the Broadway Spamalot musical. There’s a lot of name-dropping in the latter sections of his palling around with famous celebrities, not all rock stars, from David Bowie and Mick Jagger to Robin Williams. It doesn’t quite cross the line into boastful gossip, though it reminds us that the likes of Idle travel in different, more rarified and privileged circles than the likes of nearly all of his readers. Certainly there could have been more about the Monty Python TV/movie/live performances for which he’s most celebrated, but then he does talk a lot about them in several Monty Python books, most notably the oral histories The Pythons and Monty Python Speaks!