The rock book explosion kept on exploding in 2018, despite the uncertain state of the record business, the government, and the world in general. There were memoirs and biographies of everyone from superstars like Roger Daltrey and Paul Simon to artists you’d never suspect would have been (or made themselves) the subject, like the drummer of the Student Teachers.

Some of them—even some by and about artists who are big favorites of mine—were disappointing, and don’t appear on this list. But there were easily enough to fill up not just a Top Ten, but a Top Twenty and then some. There were also some worthwhile ones from 2017 I didn’t get to until this year, and as I’ve done for my past best-of lists, I’ve included supplemental picks from the previous year at the end of this one.

Most of these books were memoirs and biographies, but some of them had a different focus, whether on an album, era, or something else. One such work tops my list.

1. Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968, by Ryan Walsh (Penguin). Although much of this does discuss the genesis and recording of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks album, it’s not solely a history of that LP. Morrison was based in Boston when the material for Astral Weeks came together, and much else of interest was happening in that city that year, though it hasn’t often been documented in either rock histories or general histories of the era. Walsh also investigates the odd commune administered by folk musician Mel Lyman, who claimed to be God; the hype-driven “Bosstown Sound,” in which several so-so local bands were signed to record deals and touted as part of the next San Francisco-like scene (especially by MGM Records); the Boston Tea Party becoming one of the greatest venues for live rock concerts in the psychedelic era, functioning almost as a home-away-from-home for the Velvet Underground; and James Brown giving a televised concert right after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in a largely successful bid to quell possible rioting.

Many books that try to link several different stories into one work end up covering too little in their attempt to cover too much. But Walsh succeeds in blending all of these and more—none of which might have made for a 300-page book on their own—into an excellent, absorbing narrative. What emerges is a picture of a countercultural scene in a major city that has somewhat escaped most histories of the period. The research is deep, drawing from many interviews with the participants (though not Morrison), and the prose flows gracefully.

If you’re interested in Morrison specifically, this has many details about his life in Boston that aren’t in even the most in-depth biographies of the singer. These include details about his erratic live performances (leading the short-lived Van Morrison Controversy); fractious relationships with industry figures in Bang Records and Warner Brothers; attempts to work with local musicians, some of whom Walsh tracked down and interviewed; descriptions of obscure unreleased studio and live recordings, Walsh getting to hear an actual nearly hour-long unreleased 1968 show (briefly released on iTunes UK in late 2018) in good fidelity; and some insight into his personal life with his wife of the time, and friends like Peter Wolf, whom Van became friendly with when Wolf was a DJ on a new underground rock station. The other material, however, should interest even most of the readers principally attracted by the Morrison coverage. It’s an excellent overview of the exciting mayhem that was brewing in Boston that year, much as it did in the late 1960s in the far more documented scenes in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and London.

2. Nobody Told Me: My Life with the Yardbirds, Renaissance & Other Stories, by Jim McCarty with Dave Thompson (self-published). McCarty was drummer in the Yardbirds, for whom he also co-wrote a good deal of original material; with Yardbirds singer Keith Relf, he later co-founded the original Renaissance, going on to play in numerous other less celebrated acts and various Yardbirds reunions. His memoir is almost everything you’d hope for from a member of a great rock band. Well over half the 300-page book is devoted to the Yardbirds in the 1960s—the five years or so for which McCarty will, justly, be primarily remembered. He discusses every phase of the band’s evolution with clarity, detail, and appropriately modest humor without overdoing it. He takes pride (again without overdoing it) in the band’s astonishing accomplishments, recognizing that their hunger for experimentation and innovation was just as important as their legendary trio of lead guitarists (Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page). That sounds like what a memoir should do, but believe me, it often doesn’t, whether it’s by a rock musician or someone from another field.

There are plenty of interesting stories here that even a Yardbirds fanatic won’t necessarily have come across, whether it’s how “Train Kept A-Rollin’” ended up having its distinctive double-tracked vocal by accident, or how McCarty missed some gigs on one of their last American tours due to depression. Although the post-Yardbirds sections can’t match the rest of the text, they’re certainly entertaining, especially when discussing the strange dissolution of Renaissance after its promising beginning. Again unlike many rock memoirists, he keeps the stories of non-musical hijinx to a minimum (though there are some good ones), seeming to know what fans are most interested in and how to keep these in check.

In the absence of a quality biography of the Yardbirds (though there have been a couple half-baked attempts), this is as good a book with the band as its focus as you could want, and highly recommended. While its design is basic, it nonetheless includes a good number of worthwhile photos, many of them rare or never before seen. As a self-published work, it won’t be the easiest pick on this list to find (or even find reviews of), but it’s easy to order online.

3. Let the Good Times Roll: The Autobiography, by Kenney Jones (Blink Publishing). Jones was drummer in the Small Faces, Faces, and the Who; almost anyone who’d take a look at this memoir would know this, though all three bands are in the subtitle to remind you just in case. Although not known as the most colorful member of any of these acts, this hits most of the crucial bases that make for a fine rock memoir. It’s very detailed; candid without being catty; pays a lot of attention to the music and records, as well as the personalities; and is clearly written, with plenty of interesting stories, not all of which will be familiar to fans of his groups. And though the Small Faces weren’t nearly as successful or famous as his subsequent two bands (especially in the US), Jones actually spends more time on them than the Faces or the Who.

It seems the Small Faces are where Kenney had his best times, and that they’re the band he holds closest to his heart, though his frustration with the breakup caused by Steve Marriott’s departure is still evident. Drugs and other hedonism troubled the operations of his post-’60s acts to some extent. And while the Who gave his biggest payday, he’s frank about the failure of the band to reach their full potential during his stint with them (in part because of Pete Townshend’s failure to give them all his best material), as well as his strained relationship with Roger Daltrey. He also writes poignantly about his affection for Ronnie Lane in particular, and his regret over the illness that caused Lane’s premature decline and death.

Yes, there are some sections on the hobbies that many stars feel should be written about in books like this, even if they don’t interest fans nearly as much as the music. In Jones’s case, it’s polo and helicopters, as well as some sentimental childhood memories before the story really takes shape. But those sections, thankfully, aren’t that long, the bulk of the text dealing with his musical life and times from the early 1960s to the early 1980s. It’s a high-quality, highly readable, and likable book that got surprisingly little attention upon its release, and deserves more.

4. Thro’ My Eyes: A Memoir, by Iain Matthews with Ian Clayton (Route). The parade of memoirs by Englishmen continues with this work by a singer-songwriter most known for his time with Fairport Convention, Matthews Southern Comfort, and Plainsong in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, though he’s remained an active recording and performing artist since then. He’s been through the highest highs—a #1 UK single (and substantial US hit) with a cover of Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock” and a #13 US solo hit in 1978 with “Shake It”—but also the lowest lows, couch-surfing when he’s been between labels, jobs, and relationships.

This swing between the extremes isn’t rare for musicians, but it’s not often told as well as it is in Matthews’s account. It’s plain-spoken; detailed about most phases of his career; and told with a personal flavor uncommon in books done with a collaborator. Even if you’re not familiar with his work beyond his first and highest-profile decade, the subsequent sections are pretty interesting, covering not only his wandering from London to Los Angeles and Seattle to Austin and Holland, but also a stint as an A&R man for Windham Hill. It’s also a reminder that after the 1970s, a lot of under-the-radar music was made by figures like Matthews that wasn’t as flashy or radical as the kind covered in hip indie magazines, but popular enough to sustain a following and performing/recording career.

His mishaps in the studio and onstage, tensions within bands, and failed relationships—and there are quite a few of these—are told with a calm acceptance as part of the deal of working in a volatile music business. His dysfunctional family background also holds some sobering surprises. If you’re most interested in the purely musical side, there are a lot of observations about his songs, records, and legends he’s worked with, including Sandy Denny and Richard Thompson. It’s highly recommended both for its historical value and as a quick-paced, absorbing reading experience.

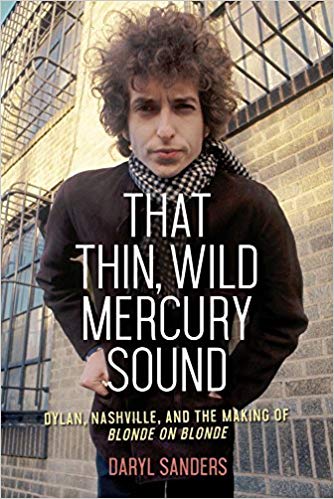

5. That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound: Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde, by Daryl Sanders (Chicago Review Press). For an album so roundly acclaimed as one of the greatest of all time, a lot of mystery has surrounded Blonde on Blonde. It will continue to do so, but this full book on the double LP is certainly the most in-depth account of its genesis, especially considering that details are sketchy even in some of the better Dylan books. The greatest point in its favor is that Sanders actually talked to several of the people involved in the recording—not Dylan himself, but the late producer Bob Johnston, and quite a few of the Nashville session musicians enlisted to back him (as well as Al Kooper).

With the emergence of recording session details and, especially on the 18-CD collector’s edition of The Cutting Edge 1965-1966, a wealth of outtakes, much more is known about Blonde on Blonde than was the case even ten years ago. But the author ties together its complicated evolution with clarity, starting with the unsatisfactory New York sessions in late 1965 that predated the bulk of the ones a few months later in Nashville. He also connects the record to the Nashville music/recording scene in general, and offers descriptive analysis of the songs themselves, including some overlooked obscure recordings that influenced the compositions. There are also sections on the album’s reception, influence, and artwork, as well as some uncommon illustrations, including manuscripts used at the sessions for a couple songs.

6. All Gates Open: The Story of Can, by Rob Young & Irmin Schmidt (Faber & Faber). There was a previous, unsatisfactorily perfunctory biography of Can, but this is really the first book to tell their story well. As an opening clarification, although Rob Young and Can member Irmin Schmidt are credited as co-authors, they actually didn’t write text together. The bulk of the volume—about 350 of the 550 pages—is a standard biography solely written by Young, while Schmidt “authored” the remaining 200 pages of interviews and diary entries.

It’s really Young’s section that gives this its value. He interviewed all four core members from Can, also drawing on extensive interview material with their colorful singers (in different eras) Malcolm Mooney and Damo Suzuki, and some others who drifted in and out of the band, if only on a part-time or supplementary basis. He spoke with other associates ranging from roadies to girlfriends, and describes all of the recordings in their extensive discography (including some very obscure ones and side projects), along with more video footage than almost anyone suspected existed. Yet it’s not a dry connection of details, putting the music in context with the German rock of the time, the overall European scene (including their UK tours), and the intersections between rock and serious contemporary composers that informed their work. Some pretty interesting little known nuggets pop up regularly, like Karlheinz Stockhausen’s letter attempting to stave Suzuki’s deportation (which was prevented by a different intercession from a major political figure), or Holger Czukay contributing to the band’s breakup by telling Schmidt’s wife Irwin was having an affair. The members’ post-Can projects and semi-reunions are covered, but not too extensively or more than necessary.

Schmidt’s part of the book should be considered an appendix, not a second half or something of the sort. Much of it’s devoted to transcriptions of interviews—not traditional ones where someone asks Schmidt questions, but roundtable discussions of sorts in which he participated with other musicians (most of whom started their careers after Can’s prime), artists, and other non-musical figures. Some interesting Can stories and observations dot these conversations, but really, there’s too much non-Can digression to belong in a book like this or jibe comfortably with the main biography. There are also Schmidt diary excerpts—not from the Can days, but from 2013 and 2014—that have far less Can-centric material. If the addition of Schmidt’s sections raised the price of the book, it would have been better not to use them, though considering the price is a not unreasonable $29.95, it might have made little or no difference to its cost. They can be treated as bonus tracks of sorts, skimmed or left unread if your primary interest is a quality conventional Can biography, which Young’s part supplies.

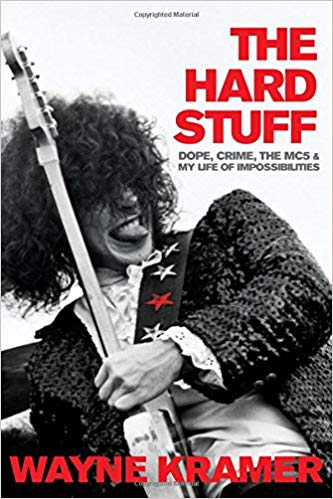

7. The Hard Stuff, by Wayne Kramer (Da Capo Press). Most known as guitarist in and (certainly as he tells it) leader, if anyone was, of the MC5, Wayne Kramer has written an expectedly hard-hitting, plainly spoken memoir of a journey that was both exhilarating and punishing. The first half of the book details his time in the MC5 in considerable depth, and that’s likely the chief attraction for most people interested in his career. The second half, also in detail, delves into his rough post-MC5 years, which found him not just often musically adrift, but also drifting into hard drugs and not-so-small-time crime. That landed him in prison for a few years. While that was decades ago, it was a hard climb back to both professional and personal stability, with plenty of other shaky musical alliances, serious dalliances with drugs and alcohol, and sketchy characters along the way.

In limited reaction from some readers and MC5 fans I’ve seen, this bio has gotten a mixed reception, especially from some who feel he’s overblown his role. I did like the book, though. He discusses his musical highs and personal lows with hard-nosed comprehensiveness. It neither glosses over nor laments, or excuses himself for, the toughest and most controversial situations he faced and actions he took. I wouldn’t have minded, actually, some more coverage of specific records and songs; the exciting, distorted pre-Elektra album singles the MC5 did are barely mentioned, for instance. I admit I’m not as expert on the MC5 as I am on many other acts of the era, but there were still some unfamiliar stories to me, like his account of sessions for a second Elektra album that got aborted; his accounts of how he, and not Michael Davis, played bass parts on Back in the U.S.A.; and how cold industry figures like Atlantic’s Ahmet Ertegun turned on the group when they didn’t sell loads of records. More surprising is how cold relations turned between Kramer and manager John Sinclair when Sinclair was sent to prison, though they patched things up.

If the second half of the story isn’t as compelling as the first, it’s still pretty interesting for the most part. For one thing, not many memoirs spend so much time on the down-and-out portion of an artist’s life, and not many artists lives were as down and out as Kramer’s. Even post-prison, his struggles with substance abuse dragged out for so many years that you do find yourself starting to wish he’d finally kick his drinking habit instead of repeatedly relapsing. He finally does, near the end, where (in common with many such memoirs) the years speed by much more rapidly. But most of the ride makes for good if sometimes disturbing reading, with insights into the tension between art, politics, and music business commerce that are well worth weighing.

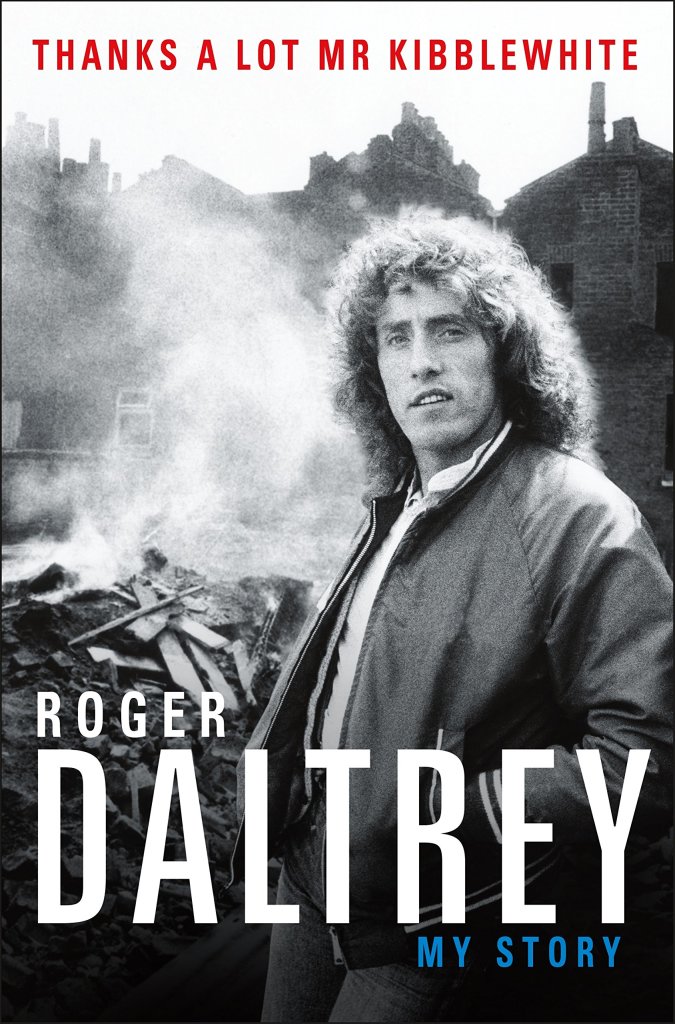

8. Thanks a Lot, Mr. Kibblewhite: My Story, by Roger Daltrey (Henry Holt). Daltrey’s memoir is only half the length of Pete Townshend’s (Who I Am, published 2012), and if you’re looking for details about how many of their songs were recorded or why some of their B-sides were chosen, they’re not abundant. Nonetheless, I liked it, even if I would have liked more depth. In keeping with most people’s perception of the group’s dynamic, Daltrey’s straightforward and no-nonsense, where Townshend tends to be reflective and at times meandering. He also displays more humor, if in a subtle way, than you might expect, making his pride in the Who obvious without getting overblown or pretentious. And there are a lot of good stories here that aren’t all familiar to Who fanatics like me, especially on the band’s formation and complicated road toward their first hit records in 1965. If some classics are barely discussed or not discussed at all, there are still anecdotes about, to take just a few examples, how the vocals developed for “My Generation”; how he felt uncomfortable vocalizing “I’m a Boy”; how he helped write the bridge of “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere”; or his unhappiness with how his vocals were mixed on Quadrophenia.

There’s also some honest perspective on his complex, if by now quite friendly, relationship with Townshend; the laughs but, more often, aggravation of putting up with Keith Moon; and the financial irresponsibility of managers Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp. If you want more personal, somewhat salacious admissions, a few are here, like his 1965 loan (paid back) from the notorious Kray twins; his mild dalliance with downers in the 1970s; and his little-reported first marriage. He never dwells on these too often, though, in a refreshing contrast to many rock memoirs that go on about such non-musical matters at inappropriate length. I would have liked more (or virtually anything) on the few Who songs he wrote or co-wrote; if you want to find out how his folky “Here for More” wound up on a 1970 B-side, you’ve come to the wrong place. But it’s a good if pretty quick read, the bulk of it dealing with the Keith Moon era, the past few decades of Who tours/reunions occupying relatively few pages.

9. The Girl in the Back: A Female Drummer’s Life with Bowie, Blondie, and the ‘70s Rock Scene, by Laura Davis-Chanin (Backbeat). As Laura Davis, the author of this memoir was drummer in the Student Teachers, a late-’70s New York new wave band that put out a single on the Ork label, as well as getting a couple cuts on a compilation produced by Marty Thau. Unless you were paying pretty close attention to that regional scene then or collecting it now, it’s unlikely you’ve heard of them. They were one of many groups springing up in the wake of the first flowering of the CBGBs scene, many of whom, like the Student Teachers, not only didn’t achieve fame, but never released an LP.

But this book is pretty good, whether or not you’ve heard of her band. Rather unbelievably, she was still going to high school—which she barely finished—while the Student Teachers were playing New York clubs, getting to know some of their inspirations. In Davis’s case, she got to know some of them pretty intimately, becoming the girlfriend of Blondie keyboardist Jimmy Destri, with whom she lived for a while (and while still in high school). Destri also produced the Student Teachers, and helped introduce Davis to Bowie, with whom Jimmy played for a bit. And Destri doesn’t come off well in this book, struggling with substance addiction and egotism, and often treating Davis poorly, physically abusing her on occasion.

His name’s foregrounded in the subtitle, but Davis didn’t actually know Bowie that well, although she hung out with him alongside Destri a few times. The book’s more notable as an account of young, enthusiastic teenagers getting so galvanized by the New York punk/new wave scene that they formed a band, getting a sniff of the big time before, as so often happens, drug problems and infighting wore them out fast. In some respects, Davis remained a normal teenager, watching network sitcoms, making money as a babysitter, and struggling to pass high school exams. In others, her life was utterly unusual, not quite successfully balancing those activities with nocturnal clubbing, drugs, sex, and rock’n’roll in the New York underground (which was swiftly becoming overground as bands like Blondie got hits). A good storyteller, she writes about the music and the lifestyle with candor (if occasional sentimentality), including her diagnosis with multiple sclerosis after getting thrown out of the Student Teachers. You can read my interview with her about the book here.

10. Paul Simon: The Life, by Robert Hilburn (Simon & Schuster). There have been previous biographies of Simon (and Simon & Garfunkel), most of them not very good. This has the crucial advantage of being the first to draw upon extensive interviews with Simon himself, along with many of his associates (though not Art Garfunkel), some of whom, like his ex-wives, have seldom or never spoken to biographers. It’s a thorough account of his rise from Brill Building hopeful to folkie, folk-rock stardom with Garfunkel, and his eclectic and largely hugely successful solo career. It’s not extremely lively, but then, Simon hasn’t had the liveliest of celebrity rock star lives, though it’s been interesting enough. As you’d expect, interest lags in the final sections, and his post-Graceland work—thirty years—only takes up about a quarter of the book, though there’s no reason it should occupy more space. This doesn’t make the best of the previous Simon bios (Peter Ames Carlin’s Homeward Bound: The Life of Paul Simon, from 2016) redundant, but it is the best overall book on the singer-songwriter, and likely to remain such, given the exclusive access to the subject.

11. All in the Downs, by Shirley Collins (Strange Attractor). Collins is a legend in British folk music with a recording career stretching back to the mid-1950s (albeit with a very long break after the 1970s), though she’s far less known in the US than the UK. Her memoir is uneven but more often than not extremely interesting, both for her memories of her own music and her intersections with many notable figures. From the very dawn of the British folk revival, she was a crucial figure, both for her distinctively husky-yet-high voice—a likely influence on Sandy Denny, among many others—and her role in popularizing, if primarily in the folk community, many traditional British songs. She looks back on her life with candor and, though it’s not a dominant element, some humor, not smoothing over the rougher professional and personal patches.

Collins doesn’t give equal weight to the most significant records of her career. There’s a lot of detail about her notable collaborations with her sister/organist Dolly, and guitarist Davy Graham. There could be more, though, on her 1970s work with the Albion Band, the closest she got to rock music. There are fairly frequent interjections of general observations about British folk music, and extensive quotes of lyrics from some of her favorite songs, that are not as notable as her recounting of her own experiences. Her writing is good, but the focus is somewhat diffuse and wavering.

As for the notables with whom she crossed paths, there are plenty of details—some painfully honest—about her 1950s affair with Alan Lomax. (There’s more about that in her previous book, America Over the Water; if you’ve read that, note that there’s not much overlap between that volume, which concentrated mostly on her 1950s trip to the US to collect field recordings with folklorist Lomax, and this overall autobiography.) There’s also a lot about her 1970s marriage to Ashley Hutchings, in which the Fairport Convention/Steeleye Span/Albion Band stalwart comes off for the most part as a cad. (She broke up with first husband Austin Marshall, as she remembers in one of the more candid sections, in large part because he “loved jazz and I hated it.”) And there are sections of less, but still at times noteworthy, interest about her struggles to support himself after withdrawing from professional singing in the 1980s, and her comeback in recent years.

Here is a passage, by the way, bound to warm the heart of every music nerd who has endured scolding from parents and other authority figures for “wasting” money on records and books, in remembering working at Collets Bookshop in London as a teenager: “It was here I found the two volumes of Cecil Sharp’s and Maud Karpeles’s English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, a collection that was, at that time, unknown to me. They were priced at 63 shillings for the two volumes, one of ballads, the other of songs. I bought them with my first two weeks’ wages – 32 shillings a week. I had to live very frugally for a while, buying buns for lunch from the baker across the road, and a packet of dried chicken noodle soup for my evening meal. With no protein and no vitamins I got very run-down that winter, and had painful chilblains on my heels. It’s called ‘suffering for your art,’ but I maintain to this day that it was the best money I ever spent.”

12. Bring It On Home, by Mark Blake (Da Capo Press). For all their success, Led Zeppelin’s manager, Peter Grant, has been a somewhat murkily documented character, if notorious for some incidents of thuggish behavior. This biography does a good deal to flesh out the story of this rather larger-than-life figure, even if some of the seamier stories that have circulated around him turn out to be exaggerated or, perhaps, never have occurred. Although his childhood and early adulthood remain pretty shady, the picture gets clearer with his entry into the rock’n’roll business in various lower-level capacities with Gene Vincent, the Animals, producer Mickie Most, and others, eventually resulting in him being handed the manager’s reins for the Jimmy Page-era Yardbirds almost by accident. Some of the book’s most interesting sections are in these early chapters, which give a sense of how the UK music industry was reinventing itself on the fly during the British Invasion, when brasher and more assertive rock bands were changing the rules with unprecedented speed.

Grant distinguished himself enough in his year and a half as Yardbirds manager to stay in that position when Page formed Led Zeppelin. (As an aside, in one of the volume’s more interesting anecdotes, Page contends that contrary to many reports, Dusty Springfield did not play a role in getting them signed to Atlantic Records.) Drawing on interviews (not all done specifically for the book) with everyone in Zeppelin except John Bonham, and previously unpublished interviews with Grant himself, a portrait emerges of a man who could be effectively boorish and threatening on behalf of his clients, yet also fiercely devoted to their artistic freedom and financial gain.

There really isn’t enough Grant-centric material to make a long book, and it also covers much of Led Zeppelin’s general career along the way. That doesn’t get in the way, however, of a reasonably informative and entertaining tale, also taking in the band’s Swan Song label, whose clients included Bad Company, the Pretty Things, and lesser-known acts like Detective and Maggie Bell. Grant’s decline—coinciding roughly with Led Zeppelin’s dissolution, and, like many a rock star, involving substance abusive and general erratic behavior—is also covered, though the post-Zeppelin years are understandably only sketched out. I find Led Zeppelin more interesting to read about than to listen to, and this work falls squarely into that category, both for its examination of a complex man and its reflection of how rock management changed (and to some degree needed aggressive managers to give their clients a fair deal) as the rock business grew to elephantine proportions in the 1970s.

13. I Brought Down the MC5, by Michael Davis (Cleopatra). Published six years after his death, the memoir of MC5 bassist Davis appeared the same year as the autobiography of fellow MC5er Wayne Kramer (see review earlier in this post). The pair will generate some unavoidable comparisons, especially as they offer some differing perspectives on the group’s stormy career and demise. I’m not enough of an MC5 fanatic to champion one side of a debate, but I do think Kramer’s book is more detailed and better written. But Davis’s work is still worthwhile, even if it’s not as focused and the production values are a bit rudimentary.

There are some similarities to the two’s lives. Both had a tough post-MC5 life that saw spells in prison, drug dealing, and substance abuse, though generally Kramer ultimately pulled himself together better. Davis is neither proud of nor apologetic for his behavior, recounting with candor that verges on the matter-of-the-fact. If you think that’s cool, think again: that behavior included DUI, leaving the scene of an accident he caused, telling a woman she was on her own after she informed him he’d made her pregnant, and hitting that woman years later (they ended up living together anyway; long story). Looking back on those mishaps with honesty doesn’t make them any less harmful.

As for the music and the MC5, yes, there’s plenty of that, including his exhilaration as the band morphed from a high-energy cover act to something more original and revolutionary. If the coverage of the records and their label relations is a little spotty, there are still plenty of interesting memories of recording their albums (and their obscure pre-LP singles); the frustrations of not reaching a wide audience and being abandoned by the companies that signed them; and the tensions that led to their piece-by-piece dissolution. There’s also, as in Kramer’s book, a good deal of space for his post-MC5 drift through numerous bands of variable quality, most famously Destroy All Monsters. There’s nothing on his final decade—maybe he just ran out of gas for the project, even though that final decade included reunion performances with Kramer and MC5 drummer Dennis Thompson. That’s just as well—that’s not the era that’s most interesting, and there’s plenty here.

14. Reinventing Pink Floyd: From Syd Barrett to the Dark Side of the Moon, by Bill Kopp (Rowman & Littlefield). With the abundance of literature about Pink Floyd, is there room for yet another book on the band, albeit one focusing mostly on the years between 1968 and 1973? Yes, and not just because these are the most interesting years of their career, save for the pre-1968 Syd Barrett era. As a disclaimer, I did write one of the back cover blurbs for this volume. But I stand by what I stated: that it combines research into their classic albums and a wealth of little known and unofficial recordings with astute and entertaining analysis. Unlike many historians, Kopp digs into specific songs and recordings both in detail and with perceptive, highly readable commentary. These include not just the official LPs, but also early non-LP singles, the abundance of material that recently became available on the huge Early Years box, and quite a few live and studio tracks that remain unofficially available. Usually such more obscure work is simply noted and/or catalogued in books, but Kopp integrates his descriptions and evaluations with the story of their just-post-Barrett evolution as a whole. Not a lot of first-hand interviews were done for the book, but they do include some figures with interesting comments on the early Pink Floyd story, such as early co-manager Peter Jenner, Humble Pie drummer Jerry Shirley (who drummed on some Barrett solo recordings), Ron Geesin, Steve Howe, and Nice guitarist Davy O’List.

15. Long Distance Voyagers: The Story of the Moody Blues, Vol. 1 (1965-1979), by Marc Cushman (Jacobs Brown). Considering their popularity, it’s a little astonishing it took until 2018 for a truly comprehensive biography of the Moody Blues to hit the market. (Nerd note: Although the publication date is given as December 10, 2017 on the copyright page, it did not ship until January 2018.) This isn’t a great rock bio, but it certainly is thorough, taking up nearly 800 pages (though the final 80 or so are devoted to a discography, bibliography, and footnotes). While only two of the five main members (Mike Pinder and the late Ray Thomas) were interviewed by the author, it draws from a staggering wealth of vintage interviews and reviews. Thus it reconstructs and guides the reader through all of their recording sessions and tours. The focus is on the 1967-1972 period that saw the recording of their seven most beloved albums (starting with Days of Future Passed), but their earlier R&B/British Invasion pop period with Denny Laine as lead singer and (with Pinder) main songwriter is not neglected, getting a lot of space too (with Laine’s post-band activities getting some coverage as well). Their less interesting mid-to-late-’70s period, dominated by solo/duo albums and a comeback with 1978’s Octave, is also dealt with in depth.

This wealth of info does have a downside. If you’re not a Moody Blues fanatic, the sheer bulk of quotes from album and concert reviews (as well as detailed lists of how well some of their singles performed in specific radio charts all over the US) can be too much. Having all that material at hand is kind of neat, but it’s used so heavily that the book’s not as readable as other huge rock bios that employ similarly deep research, such as Johnny Rogan’s 1200-page Byrds tomes. The author’s frequent interjections of fannish, personal rebuttals to the band’s negative reviews (of which there were a good number) are unnecessary and diminish the objectivity that would give his work greater credence. There is also such an abundance of typos, with many of the years referenced just one digit off, that it seems like the book might have been rushed through production. Even the years in the title are given differently on the cover (1965-1979) and the copyright page (1964-1979). Still, the sheer quantity of information makes this worth having for those with a serious interest in the group’s creative prime, especially as many of the nuts and bolts details of their career have remained surprisingly obscure given the band’s popularity.

16. The Beatles on the Roof, by Tony Barrell (Omnibus Press). On January 30, 1969, the Beatles famously gave their last live performance on the roof of Apple Records in London, filmed for posterity for the Let It Be movie. Much has been written about that occasion, but can you make a whole book out of it? Barrell does, and fairly successfully, though he needs to cover a lot of other things going on in the group’s career in late 1968 and early 1969 to pad it to book length. Even then it’s not too big (175 pages), and some references to contemporaneous non-musical developments in world affairs are kind of gratuitous, and could easily have been cut.

Still, nearly half a century after the event, Barrell did manage to incorporate some fresh research, including interviews with people who were there—Let It Be director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Beatles business associate Peter Brown, assistants to the Beatles, the Apple receptionist, and even a number of fans and policemen who managed to watch the concert. Even Beatles fans who know a great deal about this period might find some interesting stories here that haven’t been often reported, like George Harrison’s attempt (which apparently didn’t get too far) to write a musical about everyday life at Apple with publicist Derek Taylor. It’s a quick read that might go over some familiar territory for Beatles fanatics, but ties together the events leading to the performance pretty well, also covering some other key factors (especially in their January 1969 recording and film sessions) leading to tension within the group.

17. The Doors: Summer’s Gone, by Harvey Kubernik (Otherworld Cottage Industries). Over a period of decades, Kubernik’s done interviews with all the Doors (except Jim Morrison), numerous close and not-so-close associates of the band (ranging from producer/engineer Bruce Botnick to a bodyguard), and numerous people who just saw wrote about or had some contact with them. Excerpts of many of these, plus a few reviews, are in this oral-histories-of-sorts anthology.

The design’s basic low-budget and the organization is a little scattered. But for the serious Doors fans (I’m one), there’s a lot of interesting stuff here, albeit with some fairly trivial material and inessential basic Doors criticism/appreciation in the mix. There are, as examples, interesting instances of unsuspected recordings by the likes of Jimmy Smith and Blood, Sweat & Tears cited as influences on specific Doors songs—not only by whimsical critics, but also by the Doors themselves. There are unexpected encounters Morrison had with stars like the Guess Who’s Burton Cummings, and fairly revealing comments from figures not often interviewed for other Doors histories, like one of Morrison’s numerous girlfriends, Anne Moore. This is by no means among the first Doors books you should pick up, but it’s a worthwhile addition to the shelf if you want to hoard as much as you can about the group.

18. Channelling the Beat!: The Ultimate Guide to UK ‘60s Pop TV, by Peter Checksfield (peterchecksfield.com). This hefty (700-page) tome is much more a reference book than a sit-down-and-read experience. Certainly it’s for serious collector nerds – the kind who want to know as much as possible about when and where almost every United Kingdom pop-rock act of the ‘60s appeared on film, including TV programs, promo clips, and movies. While most of this is sheer listing of such details, it’s doubtful a more thorough such work could ever be compiled. Checksfield covers the filmography of 150 UK artists, from superstar rock groups to women solo singers, cult acts like the Sorrows and the Action who never had much or any chart success, and pop-oriented people who never made an impact in the US. Sometimes he also covers their post-1960s clips, though the cutoff date varies.

He doesn’t miss much, although if you’re so inclined, you’ll note the absence of interesting groups with limited success like Scotland’s Poets, and pretty big ones who started their career near the end of the 1960s (like Deep Purple, Jethro Tull, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown, Family, and Ten Years After). If you’re as steeped in this stuff as I am, you might find the very occasional missed clip (like Chad & Jeremy’s appearance on The Dick Van Dyke Show, albeit as the fictional “Redcoats”). But to my knowledge, there’s barely anything that escaped coverage. It doesn’t all read like an index, as there are some interesting details (beyond the mere dates and locations) about many of the clips that do survive for viewing. Indeed, I wished he’d put in some more such commentary, as he clearly knows the subject well, though he’s pretty generous in his assessments of the artists’ music. Then again, that might have made this already-floppy volume so big it would have been unpublishable. It’s certainly a valuable reference work on a topic no one’s tackled with such seriousness, and will send you online to look for many of the clips you’ve never seen, or even suspected existed.

19. Wasn’t That a Time, by Jesse Jarnow (Da Capo Press). Subtitled “The Weavers, the Blacklist, and the Battle for the Soul of America,” this is more about the Weavers than it is about the blacklist. But the Weavers did interweave, so to speak, more with their times than most major musical acts, getting targeted by a McCarthy-era blacklist that put them out of work for a few years. This is for the most part a Weavers biography, following the four principal members from their early-1940s roots in the left-wing folk group the Almanac Singers through their astonishing huge commercial success in the early 1950s and their reunions (some with altered personnel) from the mid-1950s onward. The author draws upon some rare documents and letters to aid research into a story where the most of the principal figures are no longer alive and available for interviews.

It’s good to have a book focusing on the Weavers, whose career is also covered in parts of, but not the focus of, biographies of members Pete Seeger and Lee Hays, as well as the memoir of another, Ronnie Gilbert. Still, it could have been better. The prose is sometimes too lofty or cutesy—the story’s interesting enough not to need such embroidery—and the transitions between their career mileposts are kind of clunkily documented, leaving some gaps and curiosity to hear more detail about some of their records. The essentials are here, including some aspects of their work that are seldom documented, such as a flop 1958 single incorporating elements of rock’n’roll (“Take This Letter”) so obscure it can’t even be called up online. Their serious and mild dalliances with left-wing politics are also examined, as are the folk community’s mixed reactions to their commercial success. However, it feels like it should have been a livelier and easier read.

20. Siren Song, by Seymour Stein with Gareth Murphy (St. Martin’s Press). Seymour Stein’s had a long and interesting career in the music industry, as an A&R man and, most famously, chief of Sire Records. His memoir is for the most part interesting, though your mileage will vary according to what era draws you the most and which artists he worked with are your favorites. For me, the best parts were the chapters on his lesser known pre-late-’70s years, starting with a teenage apprenticeship at King Records in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Stein had a long climb to his success at Sire in the late 1970s with punk and new wave artists the Ramones and Talking Heads, bouncing around with different positions before co-founding Sire in the late 1960s with another colorful industry figure, Richard Gottehrer. Some of the best stories detail his chasing down UK artists, and/or US rights to same, who were neither that big nor much like the Sire music Stein is most associated with, like Fleetwood Mac in the Peter Green era, the Deviants, and Barclay James Harvest.

Sire was pretty underground-oriented, and tuned in to the UK scene especially, as well as doing some of the first high-class reissues of vintage ‘60s rock. But it really developed as a force in contemporary music by scoring with some of the more commercial and most critically respected new wave artists, such as the Pretenders, the Cure, and Echo & the Bunnymen. Stein writes about his rise with a fairly effective balance of attention to the music business and the music itself, incorporating stories about his stormy personal life (often stormy because of his workaholic dedication to music) without overdoing it.

Sire got yet more commercial and less underground with Madonna, Depeche Mode, and Soft Cell, and even its more alternative acts, like the Smiths, were more commercial than almost anything else in the alternative scene. As the story nears the end of the twentieth century, the text focuses more on machinations (which were often cut-throat) within the music industry than the music. While these sections have their worthwhile aspects, it does start to get more like reportage of political chess than inside stories of musical evolution.

It’s also unlikely there’s much overlap between fans of, say, Peter Green and Madonna, meaning some passages will be of far less value to readers than others, no matter what their taste. In common with some other music executive memoirs, the chief linkage seems to be success, sales, and hits rather than a consistent musical aesthetic, relayed as if the reader will be equally interested in everything that made an impact.

Siren Song’s not a great book. The early sections on his childhood and adolescence are too long and sentimental; the accounts of greed and maneuvering within the industry get to be wearing by the 1990s; and his humor is sometimes witty, and sometimes sappy. Stein’s wide range of both artists he worked with and experiences in the business, however, ensure that a good deal of it will interest anyone with a generally avid curiosity about music of the last half of the twentieth century.

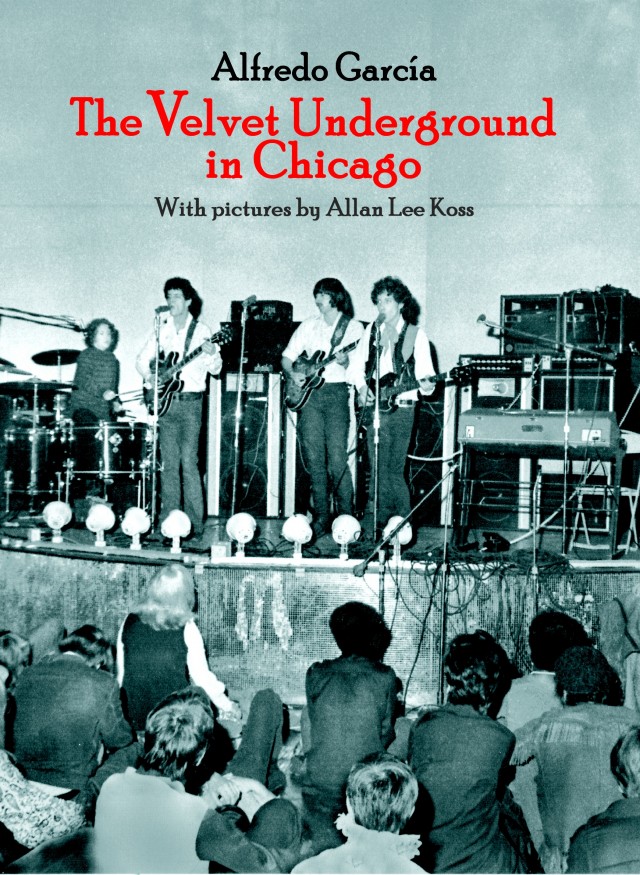

21. The Velvet Underground in Chicago, by Alfredo Garcia with pictures by Allan Lee Koss (self-published). We’re talking super-specialized, super-limited, and very much mostly of historical interest here. If you’re a fanatical Velvet Underground fan, however, you might be interested in this 68-page limited edition book. The key content is comprised of eleven previously unpublished full-page photos of the Velvets at the Kinetic Playground club in Chicago in April 1969. These are pretty high quality black and white shots of the Doug Yule lineup (who weren’t photographed on stage all that often) in action, with a couple striking pictures of Reed dominating the frame at the mike with his guitar. To fill out the slim volume, there are reprints of press clippings, ads, and posters related to all of their Chicago gigs between 1966 and 1970, some of which (like the flyer for their White Light/White Heat release party at Aardvark Cinematheque on February 1, 1968) have been seldom seen. The price is thirty Euros plus shipping and handling, and maybe it’s already sold out, as a mere 150 copies were printed.

These books were published in 2017, but also deserve mention:

1. Every Night Is Saturday Night, by Wanda Jackson with Scott B. Bomar (BMG, 2017). Roundly and deservedly recognized as the best woman singer of rock’s early years, Jackson’s autobiography is a decent overview of her music and life, if not as fiery as her finest rockabilly records. The writing’s a bit cutesy at times, but the music takes equal or slightly greater footing than her personal life—not always the case in memoirs, especially for singers who’ve had success in the country field. In fact, there’s more detail about her early songs, records, and concerts—the things that fans care the most about, as opposed to home life and religion (though there’s some of that too)—than there is in most of the memoirs by her rockabilly/country peers who came of age in the 1950s and 1960s. Jackson realizes that people who like her music are genuinely interested in her body of work—including the flop singles and obscurities as well as the most famous tunes—and gives her accounts of quite a few of these, with clarity and perspective.

While Jackson’s still an active performer, the great bulk of the book documents her pre-1970 prime as a recording artist, covering both her rock’n’roll and country sides. There are fairly interesting stories about a lot of her fellow country and rockabilly acts, and quite a bit about her dealings (largely positive ones) with producer Ken Nelson and Capitol Records, as well as her early association with Decca and mentor Hank Thompson. Later chapters deal with her embrace of faith in her later decades, without dwelling on it too much, and accompanying ventures into gospel. Her return to rockabilly in recent decades is also in the final section, including her sessions with Jack White for a 2011 album.

Naturally there will be curiosity about what she has to say about her mid-’50s relationship (actually rather brief and fitful) with Elvis Presley. She demurs from getting too explicit, but does emphasize how much encouragement he gave her to rock out instead of sticking with the fairly conventional country with which she started. It’s also notable she remembers Elvis being cognizant of larger forces igniting the rock’n’roll revolution: “Elvis was always explaining to me and Daddy that most entertainment was aimed at adults or married couples, but this new kind of music appealed directly to young people. He’d say, ‘I’m telling you, they have some money now and they’re buying the records. They’re the ones calling the radio stations requesting songs, and they can make or break you. You need to aim your songs at that audience if you want to sell a lot of records.’”

2. I, Sideman, by Jackie McAuley (www.jackiemcauley.com, 2017). Jackie McAuley’s name isn’t familiar to many rock fans, but ‘60s/’70s British rock obsessives know him as an interesting, even important, member of several fine acts. The most famous by far of them is Them, for whom a teenage McAuley played organ for a few months around late 1964/early 1965. An accomplished multi-instrumentalist, he was also the singer in the subsequent interesting Them spin-off band the Belfast Gypsies, and half of the folk-rockish Trader Horne with original Fairport Convention singer Judy Dyble. He also did an obscure but not-bad solo album in the early 1970s, played with a bunch of little known bands in the ‘70s, and played on a lot of sessions by other artists. It adds up to an interesting life, but self-published memoirs by such figures aren’t always interesting, or well written.

Fortunately, this one is, covering all of the career junctures mentioned above, as well as his family’s tough roots in Belfast and a bit on his later years, including a stint playing with skiffle king Lonnie Donegan. His brief time in Them, probably what he’ll always be most famous for, is covered in reasonable depth, including both the exhilarating musical highs and, unfortunately, the lows dealing with a punishing tour schedule and exploitative management. It’s disappointing, however, that he doesn’t say more about the Belfast Gypsies’ pretty good LP (in which he played a major role) and gets some of that band’s chronology wrong. It’s also too bad he says hardly anything about his early-’70s solo album, though he admits, with little apparent remorse, that he did nothing to promote it.

Whatever’s he’s relating, however, is written with wry humor and mature perspective, accepting the rough bumps in a journeyman musician’s road as fair trade for his compulsion to make a lifelong career out of music. Along the way were unexpected encounters, related in a very entertaining fashion, with a widely disparate array of stars ranging from Gene Vincent and Jack Bruce to Paul McCartney and Viv Stanshall. In spite of his harsh baptism by fire with Them (who fired him when the hectic pace of life on the road burned Jackie out), he offers high praise for both their music and inspiring his own musical path, enthusing about an early gig (before he joined): “Seeing the band that night was like finding the last piece of life’s jigsaw puzzle.” Although this book isn’t likely to show up at your neighborhood store or get many reviews, it’s easily available through McAuley’s website, www.jackiemcauley.com. (My interview with McAuley about the book is in the summer/fall 2018 (#48) issue of Ugly Things.)

3. Earth Bound: David Bowie and the Man Who Fell to Earth, by Susan Compo (Jawbone, 2017). I’m a big fan of the movie The Man Who Fell to Earth, and felt doing a whole book on the film (and not just star David Bowie’s role in it) was a good overdue idea. This does have a lot of detail on the movie’s origination, shooting, and critical reception, and draws on interviews with many people involved in the production (although not Bowie). Somehow it’s not as exciting a story as I’d hoped, and maybe it’s too much to expect a book on the making of a cult movie to be as interesting as what’s on screen. Filmmaking requires a lot of fairly mundane tasks, and there are stories about costume design, hauling equipment, makeup, and the reactions of locals in New Mexico (where much of the movie was done) that are more ordinary than the images being captured. Livelier are the anecdotes of how the book on which it was based made its way into celluloid form; how Bowie was enlisted to star (those stories vary); and where exactly some of the exotic scenes took place. Fans of his music in particular will be interested in the chapter on the soundtrack, especially its dissection of what exactly Bowie recorded in anticipation of his music getting used, and why none of it ended up in the picture. It’s a supplementary addition to the mounting pile of huge Bowie-related literature (including a book of pictures by the movie’s unit photographer; see review below), capably told.

4. The Raincoats, by Jenn Pelly (33 1/3/Bloomsbury, 2017). Like other entries in the extensive 33 1/3 series, this is a short (about 150-page) palm-sized book about a specific album, this one examining the Raincoats’ self-titled debut. Unlike many other books in the series, it includes material from recent first-hand interviews with the band and their manager, as well as Rough Trade head Geoff Travis, producer Mayo Thompson, and some of the Raincoats’ British post-punk peers and musicians influenced by the group. There’s also some commentary about the author’s personal reaction to the music and its feminist context, though the emphasis is on the record, its history, and its songs. There are enough interesting stories (example: they were invited to, and played in, a Warsaw performance arts festival after only having done a few shows) to make you wish the book was longer considering how much valuable source material was accessed, or that it could be expanded into a full volume on the Raincoats. What’s here does a lot to illuminate the genesis of one of the most interesting early post-punk bands, and one of the genre’s best albums.

5. David Bowie in the Man Who Fell to Earth, by Paul Duncan (Taschen, 2017). Although it’s not a coffee table book, this 480-page, 5.5 X 8 inch hardback volume features hundreds of stills and behind-the-scenes pictures by David James, unit photographer on the movie The Man Who Fell to Earth. The captions include quotes from Bowie, director Nicholas Roeg, and others who worked on the film, and Paul Duncan’s essay (in English with German and French translations) has an overview of the history of the production. I would have liked this better if the script was also included; with so much blank space on pages with the captions, as is the publisher’s custom, that might have fit. But it’s a good visual record of much of what took place in the filming, reasonably priced at $20.

6. Wild Thing: A Rocky Road, by Pete Staples (New Haven, 2017). Certainly this won’t make anyone’s best-of list unless you’re a very big fan of the Troggs and the British Invasion. But I am on both counts, so here it is, even though this slim (185-page) memoir by the bass player of the Troggs isn’t that great or informative. It’s readable, though—faint praise, but plenty of small press rock memoirs aren’t—and has some interesting stories about the murky beginnings of the band, who were actually formed from the ashes of rival groups in Andover, England. There are also some entertaining anecdotes about their biggest hits (“Wild Thing” and “Love Is All Around”), touring the UK and US, and disputes with their managers, especially Larry Page (most famous for his slightly prior involvement with the Kinks).

What’s missing? There are barely any observations about how the Troggs molded their distinct if rudimentary sound, or about most of the records—not just some of the other hits (like “I Can’t Control Myself”), but also the albums on which Staples played. Sure, singer Reg Presley was both the band’s focus and its primary songwriter, but you’d think Staples might have more to say about this. He does have plenty to say about relatively superfluous matters like his non-musical jobs, his family background, and various households in which he’s lived over the years.

There are also poignantly sad recollections of how he was unexpectedly fired in May 1969—at least, Staples himself had no idea it was coming. He’s probably unaware of Presley telling rock journalist (and co-founder of Rhino Records) Harold Bronson years later that Staples “supposedly played bass better than I, although I wonder about that now…this guy was one step simpler than we were—he was an idiot.” Staples isn’t an idiot, judging from what he wrote in his book, but he probably could have penned a better one.

7. Lucky Man, by Greg Lake (Constable, 2017). Considering Lake’s superstardom in Emerson, Lake & Palmer (and important role in early King Crimson), his autobiography received relatively little attention. That’s probably in part that’s because, sadly, he died shortly before it was published. It’s not a major work, not going into as much depth as many memoirs by comparable figures do, and with a rather light skipalong tone that doesn’t linger on many incidents too long or ponder on interior motivations too much. Still, it has its share of interesting stories about early King Crimson and ELP, the latter group expectedly taking up the bulk of the book, as he was with them much longer and much more famously. Lake hasn’t always been recalled with fondness by his associates, but he’s a likable narrator, recounting the genesis of numerous songs and albums without getting immodest, also touching upon the most memorable tours and concerts. The story does drag after ELP break up and Lake (in common with Keith Emerson and Carl Palmer) drift through fairly forgettable solo and group projects and reunions, though his admission (at the very end) that he was suffering from terminal illness as he finished the book is poignant.

8. A Foreigner’s Tale, by Mick Jones (Rocket 88, 2017). As the title makes clear, this is the Mick Jones from Foreigner, not the Clash guy of the same name. Foreigner was by far his most successful project, and non-fans of their mainstream AOR rock might justifiably assume there’s nothing to see here. But even some non-Foreigner fans are well aware that Jones had a long and pretty interesting pre-Foreigner career dating back to the early 1960s. Those readers should know that the entire first half of the book is devoted to the pre-Foreigner years. And they were pretty interesting, taking in a very lengthy spell in France where he collaborated with top French pop stars Johnny Hallyday, Sylvie Vartan, and Francoise Hardy, as well as doing a stint with Spooky Tooth upon his return to the UK in the early 1970s.

This isn’t the most elaborate rock memoir, running to a couple hundred large format pages in which the text often takes up half the space or left. That’s okay, though, because it doesn’t waste words. Jones tells his story simply, but with humor and clarity. It avoids unnecessary bloating of his days as a journeyman of sorts, his contributions usually coming as songwriter or session musician/accompanist rather than featured artist. While I did find those relatively little known days to be the most interesting focus, if you are a Foreigner fan, he writes with similar likable, keeping-to-the-essentials candor about his superstar days. Even if you aren’t a Foreigner fan, you might find many observations from this era about the way a band catches on and the machinations of the record industry (which are of course intimately related) interesting, as I did. The photos and other illustrations aren’t amazingly rare or fascinating, but complement the text reasonably well. Like other Rocket 88 books, by the way, this isn’t available in stores, but can be purchased online.

9. Memory of a Free Festival: The Golden Era of the British Underground Festival Scene, by Sam Knee (Cicada, 2017). This is a slight 144-page volume, with a few brief (if intelligently written) chapters amongst captioned photos (with a few posters sprinkled in) of free British music festivals from the early 1960s to the mid-1980s. There’s a nod to these events’ roots in folk and jazz fests, but the bulk of the content is oriented toward the rock festivals that began to sprout during the psychedelic era, continuing in some form for the next two decades, even as the music eventually encompassed punk. The photos, though, are good and offbeat, and just as often of the audience as the performers, the most colorful of these coming from the hippie period, as expected. There are some interesting artist shots too, like the Move and Tomorrow at 1967’s Woburn Festival; Phil May of the Pretty Things at the 1968 Hyde Park Free Festival; David Bowie at 1969’s Beckenham Free Festival (the occasion inspiring his song “Memory of a Free Festival”); and the Slits with the Pop Group at Glastonbury in 1979.

10. When Ziggy Played the Marquee (Iconic Images/ACC Editions, 2017). When David Bowie filmed his TV special The 1980 Floor Show at the Marquee Club in London in October 1973, it marked the last time he performed in Ziggy Stardust character. (Although Spiders from Mars Mick Ronson and Trevor Bolder were in the band, drummer/Spider Woody Woodmansey was not, Aynsley Dunbar now handling those duties.) Photographer Terry O’Neill spent the day at the club when the special was being produced, and this 205-page book is primarily devoted to his pictures from the occasion, usually focusing on Bowie, although some other participants in the program (including Ronson, Bolder, Dunbar, Marianne Faithfull, Amanda Lear, and Ava Cherry) are also seen. This was an historic event worth commemorating in book form for Bowie fans, but too many of the images are too similar to each other to mark this as a notable volume if you’re not a fanatic or near-fanatic. It’s spiced up, however, by large-print quotes and brief interviews/recollections of some of the performers and eyewitnesses, including O’Neill, Lear, Cherry, Jayne County, producer Ken Scott, and Ronson’s wife.

11. The Show That Never Ends: The Rise and Fall of Prog Rock, by David Weigel (W.W. Norton, 2017). As an overview of a much-maligned genre that’s received little serious book-length attention (aside from dedicated single-artist biographies), this is adequate, if flawed. Although he interviewed some key figures, the author relies heavily on second-hand quotes, though from numerous sources (some obscure) and properly documented in the footnotes. It covers highlights and shifts in the careers of most of the major prog-rock players of the late ‘60s and 1970s (Yes, ELP, Jethro Tull, Genesis, Mike Oldfield, and so on), and some of the more well known cultish ones (Soft Machine, Gong, Van der Graaf Generator).

Most of the focus, as is proper, is on British groups, though there’s some coverage of North American acts (like Kansas and Rush) and European ones (like Focus, PFM, and Aphrodite’s Child) who owed much to the form. Serious prog collectors will be disappointed at the scant mention of less celebrated acts, as well as the patchy attention given to the big ones. Pink Floyd, for instance, are covered, but rather fitfully, though there’s certainly no lack of information on them elsewhere. For those looking for something that simply connects the dots of the movement and pitches in some amusing/interesting stories, however, it does the job well enough. The final chapters on post-’70s prog-rock revivalists, and the descent of major prog acts into pop and reunions, are by far the least interesting, though they don’t take up too much of the text.

I’ve only read two books from your list. I totally agree with you about ASTRAL WEEKS, which is simply magnificent. Walsh gets even the smallest details right, which is rare for someone not from the area at the time . I loved the book. On the other hand, I disagree about Younger’s All Gates Open. I don’t think he tells their story particularly well and made a number of mistakes that I would think a Can fan would know, such as Damo touring with the band in Oct. ’73 (he didn’t.)… Moreover, even without Irmin’s rather unnecessary section, the book is far too Irmin-centric… It says nothing about the reason for the ill will between Jaki and Holger and other relevant problems between band members… as for other projects, it said nothing about the band that Jaki formed with musicians in Istanbul that was absolutely fantastic. After I finished the book, I wished that I’d never read it, which I never expected for a book about my favorite band.

To quote your comment from your synopsis of the Peter Grant book “I find Zeppelin more interesting to read about than to listen too”

Your taste in music cannot be trusted

Great list but only includes UK and USA releases. Each year there are some amazing books released elsewhere eg Australia. Perhaps in 2019 this list could take a worldwide view 🙂