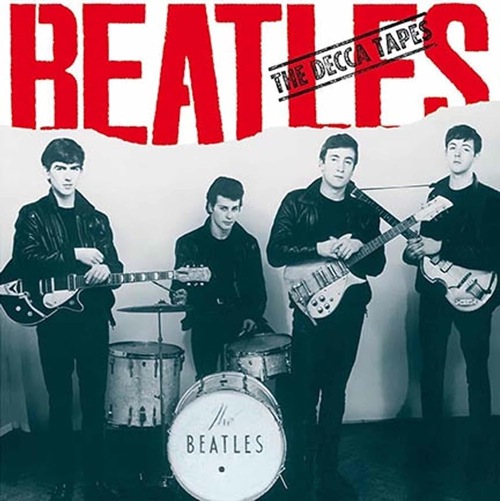

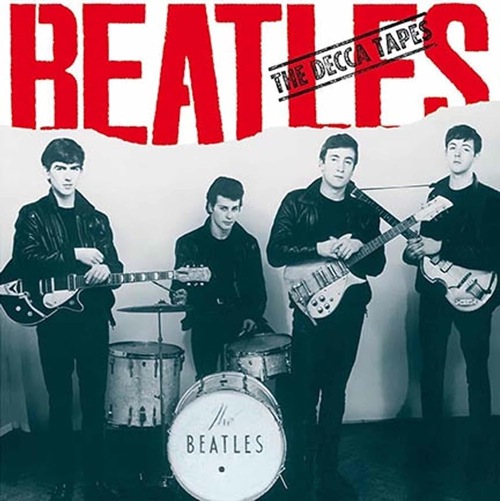

January

1,

1962

STUDIO OUTTAKES

Audition for Decca Records

Decca Studios, London

Love of the Loved

*Like Dreamers Do

*Hello Little Girl

*Three Cool Cats

September in the Rain

*Searchin’

*The Sheik of Araby

Take Good Care of My Baby

Besame Mucho

Memphis, Tennessee

To Know Her Is to Love Her

Sure to Fall (In Love With You)

Crying, Waiting, Hoping

Till There Was You

Money

*—appears on Anthology 1

Here is where the story of the Beatles’ unreleased recordings—and, it could even be said, of the Beatles’ work in professional studios as a whole—really begins. From the day John Lennon met Paul McCartney in July 1957 through the end of 1961, there had been sporadic amateur recordings of the band. None of them showed the group to great advantage; all of them would be utterly forgotten today, had the boys not unexpectedly developed in ways no one, even the musicians themselves, could have possibly foreseen. True, they had recorded in 1961 in a professional studio with a top German producer who was an international hit recording artist in his own right. But most of those tracks had been as a backing group to a journeyman rock ’n’ roll singer, affording the Beatles little opportunity for any of their own personality or originality to emerge. Their January 1, 1962, audition for Decca Records—yielding 15 songs, known for decades among collectors simply as "the Decca tapes"—was the first audio document of any kind to capture a truly high-fidelity, professionally recorded performance of a group that had already been working for five years. As a fairly well-rounded sampling of their repertoire just half a year so before they finally clinched that much longed-for recording contract, it’s of enormous historical significance. For it not only reveals what the band sounded like, more or less, just before they first established themselves as recording artists—it also illustrates just how far they had to go before they cut their first chart single eight months later. It’s also by far the most comprehensive snapshot of how they sounded when Pete Best was still in the drummer’s chair, his ousting in favor of Ringo Starr still seven-and-a-half months down the road.

The story behind how the Beatles came to be auditioning for one of Britain’s largest record labels on New Year’s Day 1962 is a long and winding tale in itself. Though it had been less than a month since Brian Epstein offered his services as manager, he’d swung into action immediately after their first meeting, even before the first contract had been signed to formalize the agreement. As an entry in the previous chapter stated, he’d played an acetate of the Beatles performing live at the Cavern for Tony Barrow that helped lead him to Decca A&R man Mike Smith. Taking full advantage of his leverage as the manager of NEMS, one of the biggest record stores in Northern England, Epstein had gotten Smith up from London to watch the Beatles play live at the Cavern on December 13, 1961. Decca was not just one of the two biggest record labels in the United Kingdom (EMI being the other), and one with a high international profile; it also knew full well the value of keeping the administrator of one of their most important retail outlets happy. Smith later even admitted that the label pretty much had to send someone to check out the group, so important was the NEMS account to the sales department.

Still, Smith seems to have been genuinely impressed by what he saw of the band onstage—albeit in front of a Liverpool audience, at the Beatles’ chief stomping ground, that was guaranteed to give them an enthusiastic reception. “The Beatles were tremendous,” he said about 40 years later when interviewed for the Pete Best DVD documentary Best of the Beatles. “Not so much my own reaction, but the crowd’s reaction, was incredible.” Such was the speed at which things could move even at major labels in those days that he arranged an audition in Decca’s London studios for just a few weeks later.

It was a big break, so they thought, and no doubt the Beatles were both excited about the opportunity and impressed that their new manager had set something up so quickly. However, the audition would not take place under optimum circumstances. There was the matter of the date scheduled, to begin with. It’s long puzzled some fans (particularly outside of the UK) why an audition would be scheduled for New Year’s Day (on a Monday morning, no less), but in the early 1960s it wasn’t yet a national holiday in Britain. It wasn’t a holiday week for the Beatles either, who had just played the Cavern on Friday and Saturday nights, and spent most of Sunday in a van with their equipment on a ten-hour drive through snowstorms to London. Driver and roadie Neil Aspinall even got lost at one point, and as if the journey weren’t enough to set them on edge, upon arrival a couple of seedy guys on the London streets tried to connive their way into using the van as a safe haven for smoking pot—still a highly exotic substance in 1961 and then, as now, illegal.

So Paul

McCartney, John

Lennon, George Harrison, and Pete Best probably weren’t in the best of

humor, or as well rested as they might have been, when they arrived at

Decca Studios in West Hempstead in North London at around 11:00 a.m.

the following morning. Brian Epstein (who’d traveled down separately by

train) was there too, and all were nervous and slightly annoyed when

Smith showed up late, having spent much of the previous night

celebrating the New Year. Then Smith insisted that the Beatles use

Decca’s amplifiers, rather than the ones they’d gone to so much trouble

to schlep down from Liverpool—not without some justification, as the

amps, not top-of-the-line to start with, had seen much wear and tear

over the course of several hundred gigs or so. (As a side note, this

particular problem wouldn’t even be fixed by the time of their

ultimately successful audition for George Martin and EMI five months

later, where some actual soldering had to be done before McCartney had

a bass amp that was deemed up to scratch. It really wasn’t until after

that EMI audition that they, with the help of funds from Brian Epstein,

started to give their equipment serious upgrades, as documented in

Backbeat Books’ Beatles Gear.)

Despite their experience recording in the studio as Tony Sheridan's backup unit in 1961, the Beatles were probably (if understandably) jumpy. Their anxiety was magnified by the studio’s red light, customary in many such facilities to keep people from entering while sessions were in progress, but a new and intimidating feature to the inexperienced musicians. “They were pretty frightened,” Neil Aspinall remembered about five or six years later in Hunter Davies’s The Beatles: The Authorized Biography. “Paul couldn’t sing one song. He was too nervous and his voice started cracking up. They were all worried about the red light on. I asked if it could be put off, but we were told people might come in if it was off. You what? we said. We didn’t know what all that meant.”

In spite of their jitters, the Beatles managed to lay down 15 songs, on two-track mono tape with no overdubbing, in the relatively small time allotted to them. (They remembered doing at least one more, “What’d I Say,” in Billy Shepherd’s obscure 1964 Beatles biography The True Story of the Beatles, but if they played it at Decca, it probably wasn’t taped.) How long this took is still a matter of some conjecture. Some sources say the session lasted a mere hour, from around 11:00 a.m. to noon—which seems like undue haste even by the standards of the early ’60s, and even considering that the 15 tracks altogether last only a little less than 35 minutes. In his autobiography, Pete Best would recall the recording kicking off around midday and going well into the afternoon. Whatever the clock really said, it may well have been a somewhat brisker audition than usual, as Smith had another group, Brian Poole and the Tremeloes, to audition later that same day. Since the tapes weren’t being laid down with the intention of release, it’s also likely that most or all of the songs were done in a single take. That was another contributing factor, possibly, to the nervousness that’s often audible in the performances, though in fairness to Decca, the audition process undergone by the Beatles was probably fairly typical for its era.

And how did the Beatles do, the ultimate verdict (more on that a bit later) notwithstanding? Frankly, the group sounded ragged and tentative, at times with a sloppiness that verged on the unprofessional. The tempos sometimes wavered and the lead vocals quavered, particularly on some notes when McCartney reached into the upper register. George Harrison’s guitar lines sometimes fumbled, as is most embarrassingly evident when comparing this early take of “Till There Was You” with the version they’d release at EMI nearly two years later, which featured a memorably beautiful and smoothly executed jazz-flamenco-tinged solo. Pete Best’s drumming was thinly textured and rather unimaginative, occasionally to the point of monotony.

Their

inexperience with

studio vocal mikes was at times obvious, some tics, clicks, and pops

getting picked up here and there, as when Paul landed on the last word

of a line (“and when I look”) in “Love of the Loved” with a “k” as hard

as if he’s biting into a cracker. The harmonies suffered from some

disorganization and faintness, though the latter quality might be as

attributable to whatever recording setup was used (and it certainly

seems like it was on the basic, perfunctory side) as to any deficiencies

in the group’s vocals. McCartney’s singing was still highly derivative

of Elvis Presley in spots, as was particularly noticeable on parts of

“Searchin’,” “Like Dreamers Do,” and “September in the Rain,” as well

as

the closing lines of “Love of the Loved.” A great role model to be

sure, but it would take some time—not very much time at all, as it

turned out—for Paul to find his own, more comfortable, yet equally

distinctive and virtuosic voice.

For most of the rest of their career, the Beatles

would perform exceedingly well, under superhuman pressure, time after

time—whether playing in front of huge crowds and TV audiences on their

world tours, writing brilliant material under strict deadlines, or

managing to match or top themselves commercially and artistically with

every new succeeding album and single. The Decca audition, to the

contrary, is about the last time we hear the Beatles actually coming

off as nervous and not wholly sure of themselves. While several songs

end with almost improvised-sounding bits where the Beatles playfully

scat, sing a super-brief operatic note or two, or laugh nonchalantly,

there’s more a sense that they’re whistling in the dark to relieve the

tension, rather than genuinely feeling at ease in their surroundings.

Yet, particularly with the benefit of hindsight, the recordings were in some respects quite promising, and not without appeal. What’s more, though no one in their right mind would put them on the same level as their subsequent official EMI-recorded material, they’re fairly enjoyable in their own right. Although the arrangements are primitive and hollow—almost to the point of ghostliness—there are strong hints of the fresh enthusiasm and vigor that would be so key to the Beatles’ approach, even on their covers of American rock ’n’ roll songs, which comprised the majority of songs at the Decca audition. It’s more present in the vocals than anything else, even if their vocal harmonies aren’t nearly as fully worked out as we’re accustomed to hearing. Still, there’s energy and exuberance, albeit in a muted form, as if they hadn’t quite yet found the courage to go for the jugular. Too, despite Best’s limitations as a drummer, there’s a youthful impatience to the arrangements that would be such a strong characteristic of the Merseybeat sound that would dominate 1963 and be exploited with greater skill by the Beatles than any other Liverpool act.

To be sure, the most striking of the 15 tracks are the three Lennon-McCartney originals, none of which the Beatles would release while they were active, although they were covered for British hits of varying size by other artists in 1963 and 1964. Indeed, those unfamiliar with the music of the pre-EMI Beatles might be first struck by the paucity of original material. Most of the songs the Beatles would cut at EMI, after all, were written by the band. More than anything else, perhaps, it’s the quality of those songs that has made the Beatles’ music so timeless (and commercially successful). It must be remembered, however, that at the beginning of 1962, Lennon and McCartney’s songwriting talents were still in a formative stage (and Harrison wasn’t writing at all, essentially, despite having co-authored the instrumental they recorded at the Tony Sheridan sessions, “Cry for a Shadow”). The three songs they presented to Decca, as meager as they were in comparison even to their only slightly later work, were probably about the best they had to offer at the time. Like the Decca tapes as a whole, these too were more promise than genius, though at the same time not at all bad on their own terms.

Of those three Lennon-McCartney-penned tracks, perhaps the most interesting is “Love of the Loved,” as it’s the only one of the threesome that hasn’t found eventual official release (the other two, “Hello Little Girl” and “Like Dreamers Do,” appearing on Anthology 1 in 1995). Even at this early stage in the Lennon-McCartney partnership, it was already the case that much or all of the writing on some of the songs bearing their byline was in reality largely or wholly attributable to either John or Paul alone. “Love of the Loved” is definitely a Paul-dominated effort, and while it might sound a tad awkward and unpolished judged next to the songs the Beatles were coming up with by 1963, it has definite hallmarks of what would often characterize the group’s compositions.

There are those unexpected, almost off-the-wall chord changes, almost to the extent that you feel this might have been one of the first times McCartney set out to deliberately explore unconventional structures; a blend of major and minor moods; the commanding glide from the bridge back to the main verse; and, as a quality prevalent in Paul’s writing in particular, an almost pervasive, haunting eerieness. A strange, skittering guitar line recurs throughout this uneasily mid-tempo arrangement, and Paul feels a little more comfortably settled into his lead vocal than he does on some other cuts, despite the aforementioned leaps into some Elvis Presley–isms. You can also hear some almost subliminally soft (and, for the Beatles, not at all typical) vocal harmonies in the background when Paul shifts into a more uplifting bridge. These indicate that there might have actually been some deliberate effort on Smith’s and/or the group’s part to give the vocal arrangement a certain idiosyncratic flavor; it certainly doesn’t sound like the backup singers are closely miked. Best’s drumming is among his better work on this session, pushing the song along with a steady insistence.

In another foreshadowing of a device the Beatles often used later, the very end of the song takes off in a surprising melodic direction, McCartney drawing out the syllables of the last line before suddenly ascending into a near-falsetto as the guitars play a brief sequence not heard anywhere else in (yet similar to the rest of ) the song. You don’t need to get into technical analysis to enjoy “Love of the Loved,” however, despite its somewhat over-serious romantic lyrics and the slightly forced pun of the title phrase. Cilla Black would have a small British hit with the tune when she put it on her first single in mid-1963, but the Beatles’ version is far superior, as Black’s used a wholly inappropriate uptempo brassy arrangement and belting vocal. As to why it didn’t appear on Anthology 1, that’s anyone’s guess; perhaps McCartney, even three decades later, was dissatisfied or embarrassed about some aspect of the song or the Decca performance. It’s too bad, as it’s certainly deserving of release, and far better than some of the other pre-EMI tracks included on that collection.

McCartney is also to the fore on the Lennon-McCartney number “Like Dreamers Do,” which did find release on Anthology 1. It’s another case of a composer and singer finding his feet, with corny sentimental lyrics that are something of a throwback to the pre-rock Tin Pan Alley era. But there are some pretty unusual things going on too, especially the lurching introduction, whose chords go up the scale until there’s almost nothing left. They don’t form a conventional progression by any means, as most nonprofessional guitarists would find if they tried to play it by ear. Still, it’s got that Beatlesque Merseybeat catchiness, if only as a bud not yet in blossom. Paul’s nervousness does seem to betray him more in this cut than in some others, however, particularly when he almost breathlessly strains for some really high notes at the end of the bridge. There’s almost a tangible sense of relief when he gets back into the more mid-range verse; the lads might have done well to knock down the tune a key or two. The way he stretches out “I-yi-yi-yi” in the bridge, too, smacks of lingering hokey 1950s rock ’n’ roll and doo wop influences that would be ironed out within the year. It’s not all Paul’s show, with Best throwing in more drum rolls (though they’re not always called for) than usual, and Harrison’s guitar going into a nice speckly line near the end, with a dated reverb that—whether due to Decca’s setup or not—would never reappear in his work on the Beatles’ EMI sessions. The Applejacks took an even jauntier, less guitar-oriented arrangement of the song into the British Top 20 in 1964. But the Beatles’ version, for all its imperfections, is far more satisfying and dare we say gutsier, even for such a relatively trivial Lennon-McCartney tune.

The final

Lennon-McCartney

song from the Decca date, “Hello Little Girl,” had been worked up by

the group for some time, as its appearance on one of their 1960 home

tapes verifies. By January 1962, it had been tightened and refined quite

a lot, the bridge bearing an almost entirely different melody. More

John’s song than Paul’s, it points the way forward to the Beatles of

1963 more than anything else recorded at the Decca audition. For while

many of the songs from the Decca tape have few or no backup vocals,

here the Beatles sound like a real group, John and Paul singing the

verse in unison, Lennon engaging in some nice call-and-response backup

harmonies in the bridge with Paul and George. Though a slight and

simple song on the whole, it’s got a rough charm (and a rather skeletal

and jagged guitar solo), and more than almost anything else the group

cut, it puts their debt to Buddy Holly front and center. The Fourmost

took the song into the British Top Ten in late 1963, and like the

Applejacks took an approach so light and sing-songy as to make the

Decca take, as innocuous as the tune was, downright earthy in

comparison.

The remaining dozen songs on the tape are all covers, and while they’re not as fascinating as the Lennon-McCartney-composed items, all of them are of some interest, even in the cases where the Beatles would later record far superior versions for EMI releases or the BBC. They also testify to the broad range of the Beatles’ tastes and the versatility of their repertoire, encompassing ’50s rock ’n’ roll, early soul, rockabilly, and even some teen idol pop and pre-1950s Tin Pan Alley. Three of the tracks would be included on Anthology 1, and seven of the remaining nine tunes would emerge in a different, later version on either a real Beatles album or the Live at the BBC collection, leaving just two cover songs from the Decca tapes that were never included on an official Beatles release in any form.

One of those two

covers is

the pop standard “September in the Rain,” based on the arrangement used

by pop-jazz singer Dinah Washington. It’s not what comes to mind when

most people think of the Beatles’ early influences, but for what it’s

worth, Paul McCartney really does sound like he’s enjoying himself on

this track, scatting with an almost ironic playfulness to kick things

off. Perhaps this was one of the later cuts laid down in the session;

on this and a few other songs, the group seems to have noticeably

loosened up. Popular standards were a part of the Beatles’ early

repertoire, usually at the instigation of Paul, though only “A Taste of

Honey” and “Till There Was You” serve as evidence in their official

studio catalog. As they did with those two songs (on their first and

second albums, respectively), the Beatles effectively adapt “September

in the Rain” to a rock guitar setting, though without nearly as much

imagination.

The other, almost equally unlikely song never

revisited by the Beatles in either a recording studio or a BBC session

was “Take Good Care of My Baby,” which had just gone to No. 1 for

American teen idol Bobby Vee in both the US and UK. This was precisely

the kind of artist, and song, that the group usually avoided in their

cover choices. Teen idol music personified the mild and soft sounds the

early Beatles were counteracting, and doing a current chart-topping

smash would be considered way too obvious for a band trying to be as

original as the Beatles were, even at this early stage in their musical

development. Perhaps this was one of the songs performed specifically at

the suggestion of Brian Epstein, who as a record retailer kept a keen

eye on what was popular on the charts, though it’s been reported that

it was George Harrison’s idea, Best claiming in Spencer Leigh’s Drummed Out! The Sacking of Pete Best

that George, “more than the others, thought we should do one or two

from the Top 20.” Nonetheless, the fellows do a reasonable if somewhat

perfunctory job on the song, which was, after all, written by one of

Lennon and McCartney’s favorite American songwriting teams, Gerry Goffin

and Carole King. George—who did more lead singing than many fans

realize in the days when the Beatles were playing mostly covers—takes

the lead vocal. Paul’s harmonies are a wee bit strained and

vibrato-laden, and the arrangement’s a little on the rushed and

tiptoeing side. In all, it’s not too much of a surprise that it didn’t

make the cut for Anthology 1.

The Coasters were

big

favorites of the Beatles, and at Decca they covered two of the great

American vocal group’s songs, as well as basing their arrangement of

the Latin pop standard “Besame Mucho” on the one the Coasters had used

in covering the same tune. That made three Coasters covers,

essentially, the most familiar of which was “Searchin’,” which

eventually showed up on Anthology 1

(where, annoyingly and for no apparent reason, the opening instrumental

bars of the song were cut off ). There’s no doubt they and lead singer

Paul McCartney loved the song; Paul, in fact, chose it as one of his

“desert island discs” in 1982. But the Beatles’ version is kind of

forced and stilted, particularly when Paul launches into a dramatic

falsetto without much of the comic flair for which the Coasters were

famous.

Far cooler is “Three Cool Cats” (also on Anthology 1), George Harrison

taking the lead vocal for a catchy minor-key,

hangin’-on-the-street-corner vignette. (Incidentally, this song,

originally used on a 1959 Coasters B-side, might not have been as

obscure as many assume; early British rock singers Cliff Richard, Marty

Wilde, and Dickie Pride sang it live on a May 1959 episode of the UK

television program Oh Boy!

and it’s quite possible that one or more of the Beatles saw that exact

broadcast.) George, John, and Paul attack the harmonies on the chorus

with real relish, though it’s a bit of a shock to hear Lennon attempt

some not-too-accomplished mimicry of Caribbean-like accents in some

brief (and not terribly funny) spoken comic interjections. Still,

overall it’s one of the best Decca cuts, as is “Besame Mucho,” which

didn’t make it onto Anthology 1,

probably because a different version (recorded five months later at

their EMI audition) was used. Surprisingly, the Decca version has a big

edge on the considerably tamer EMI one, on which for some reason the

group decided to omit the backup harmonies and infectiously silly

ensemble end-of-verse “cha-cha boom!” chants that help make the Decca

take so fun. Again, maybe it’s not the kind of song you expect to hear

from the Beatles, but it really does rock pretty hard, and maybe it’s

another one from a point in the session where they’d gotten a little

less inhibited than they were at its outset.

The weirdest

relic of all

from the Decca tape (eventually released on Anthology 1) is the cover of the

relatively ancient theatrical standard “The Sheik of Araby” (which had

actually been heard in the 1940 Hollywood movie Tin Pan Alley). Sung by Harrison as

though he’s trying to clip off the ends of each word, it’s played by

the Beatles with the absurd speed of men who’ll miss their train if

they don’t force the song under the 90-second mark (which they don’t

quite manage, failing by just a few seconds). Even more bizarre were

the nasal howls at the end of some verses, expelled with such

overbearing volume that many would guess that some wise-ass bootlegger

overdubbed them years later. But no, they were part of the original

recording, though the levity they were no doubt intended to add was

pretty contrived. The song’s inclusion in the session wasn’t as

off-the-wall as it might appear; early British rock ’n’ roll star Joe

Brown had cut a rock version of the tune in 1961, and George was a

Brown fan, taking lead vocals five months later on the Beatles’ BBC

cover of Joe’s 1962 hit “A Picture of You.” (What’s more, Brown would

become a close friend of George’s in Harrison’s later years; Harrison

would even be best man at Brown’s wedding in 2000.) As Best told

Spencer Leigh in Drummed Out! The

Sacking of Pete Best, “‘The Sheik of Araby’ was a very popular

number and we nearly did it on the BBC shows because of the demand.

George loved those kind of numbers.”

There’s not as much to say about the remaining

half-dozen songs, as all of them are inferior to subsequent versions

the Beatles would record by a wide margin. “Money,” for

instance, was one of the group’s greatest covers and a highlight of

their second album, With the Beatles.

Next to that savage performance, the Decca version is kind of anemic,

with the rushed tempo that afflicted much of the session and a far less

assertive instrumental attack. With

the Beatles included another cover first cut at Decca, “Till

There

Was You,” most familiar to American audiences from the hit musical The Music Man, although the Beatles

learned it from Peggy Lee’s recording of the song. Here the gap in

quality is yet wider, as both the rhythm and Paul McCartney’s vocal are

more hesitant than anywhere else in the session, his singing almost

faltering into prissiness with apparent nerves. It’s interesting,

however, to hear them do an arrangement here with not one but two

guitar solos, though as noted earlier, George’s playing on this

particular number would improve quite a bit by the time they recut it

for EMI a year and a half later.

While the remaining four songs weren’t redone for any of their EMI releases, the Beatles did record all of them for the BBC. In fact, in the case of “Sure to Fall” and “Memphis, Tennessee,” they did them four and five times, respectively, for the BBC, though the other pair (“Crying, Waiting, Hoping” and “To Know Her Is to Love Her”) were done on radio just once each. Carl Perkins’s “Sure to Fall” suffers most in its Decca incarnation. Though Paul excelled at this kind of rockabilly material, his voice here is as shaky as it ever was at any time on any tape, and the song is taken a shade too fast, lacking the break into double-time in the bridge that distinguished the most imaginative version they did on the BBC. Chuck Berry’s “Memphis, Tennessee” is a great song, but somehow this particular attempt, sung by John Lennon, plods a little more than it bounces, with a weird wobbling guitar chord bringing it to a finish.

Harrison takes lead vocals on Buddy Holly’s “Crying, Waiting, Hoping,” which isn’t bad at all, with well-placed responsive backup harmonies. But the BBC version is much smoother, and Pete Best, like he does throughout most of the Decca session, just pushes the beat a little too fast for comfort. “To Know Her Is to Love Her,” a No. 1 hit ballad in 1958 under the title “To Know Him Is to Love Him” for the Teddy Bears (whose lineup included Phil Spector, who wrote the song), is sung by John with major backup support from Paul and George. It’s nice to hear Lennon’s gentler side in evidence so early on, but again this pales next to the more accomplished BBC take; John’s vocal is far less confident, and there are some lingering, lugubrious doo wop inflections to the harmonies that would be scrubbed out by the time it was redone for radio in mid-1963. (Incidentally, although Hunter Davies’s book mentions that Paul sang another pop standard at the session, “Red Sails in the Sunset,” this appears to be in error. At the very least, no tape of it from the Decca audition has surfaced, though it was certainly part of their live repertoire, as proven by its inclusion on Live! At the Hamburg Star-Club recorded almost exactly a year later, and on their earliest surviving handwritten setlist, probably from mid-1960.)

Of course, there was likely little such intense analysis of the tapes at the time, by either the Beatles or Decca. The main objective of the Beatles was to get that record deal; the main objective of Decca was to determine whether the Beatles were worth recording for real. At first, Epstein and the group thought they’d done well. Mike Smith had, according to Best, said the tapes were “terrific”; they even celebrated with a dinner in London that night. They were expecting a contract to be offered soon, went back to Liverpool to resume their gig schedule, and waited. The wait turned to weeks, and at the beginning of February 1962, Decca officially turned the Beatles down. The band was devastated, and although Epstein did meet with Decca A&R man Dick Rowe and sales manager Sidney Arthur Beecher-Stevens in London to attempt to persuade them to reconsider, he was squarely rejected. Decca told him that groups were on the way out, a ridiculous rationale, as, in fact, “beat groups” would overrun the industry just a year later, the Beatles themselves leading the charge.

Much later, the Beatles were honest in assessing the merits of their performance that New Year’s Day. “We were all excited, you know, Decca and all that,” Lennon remembered in the 1970s (as quoted in Keith Badman’s Beatles Off the Record), about ten years after the big disappointment. “So we went down, and we met this Mike Smith guy, and we did all these numbers and we were terrified and nervous. You can hear it on the bootlegs. It starts off terrifying and gradually settles down. We were still together musically. You can hear it’s primitive, you know, and it isn’t recorded that well, but the power’s there. It was the tracks that we were doing onstage in the dance halls. We then went back to Liverpool and waited and waited and then we found out that we hadn’t been accepted. We really thought that was it. We thought that was the end.” In the same volume, McCartney admitted, “We couldn’t get the numbers right, and we couldn’t get in tune.” (It should be noted that it’s not 100 percent clear whether Lennon was remembering the Decca tapes accurately in his comment; he and Yoko Ono had sent Paul and Linda McCartney an acetate of what they thought were the Decca tapes as a Christmas gift in 1971, but it actually contained some of the tracks they’d recorded for the BBC!)

His enthusiasm at

the time

to the contrary, Mike Smith later claimed (as quoted in The Beatles Off the Record) that

the Beatles “weren’t very good in the studio. I took the tape to Decca

House and I was told that they sounded like the Shadows. I had recorded

two bands and I was told that I could take one and not the other. I

went with Brian Poole & the Tremeloes because they had been the

better band in the studio.” In Best

of the Beatles he added, “With hindsight, it’s unfortunate that

that excitement [of the Cavern show he’d witnessed] couldn’t have been

carried into the actual audition, which I have to say I think was very

much a disappointment. It transpired later that they had written some

wonderful songs that didn’t appear that day, and so sadly, I said no. I

certainly didn’t envision them turning into the phenomenon that they

were, which I regretted bitterly over the years. In terms of how they

were as musicians . . . certainly the one that played the most bum

notes was McCartney. I was very unimpressed with what was happening

with the bassline. [In McCartney’s defense, he’d only been playing bass

for less than a year, having taken over the bass position when Stuart

Sutcliffe left the band for good sometime in 1961.] But . . . we’re

talking about four young men in a very strange environment, probably a

very overpowering environment. And as much as we tried to be friendly,

it was a foreign area for them to be in.”

Poole & the Tremeloes were a London band, which

also seems to have been a factor in the decision, it being felt it

would be easier to work with a local act than one that would need to

travel down from Liverpool to Decca’s studios. And, in fact, Brian

Poole & the Tremeloes would come up with four British Top Ten hits

and several smaller UK chart singles between 1963 and 1965, though of

course they enjoyed nowhere near the ultimate success of the Beatles.

This hasn’t prevented a hailstorm of derision directed toward Decca

over the last few decades for their apparent misjudgment, even though

many qualified observers (and the Beatles themselves) were willing to

admit that no one could have predicted how great the band would quickly

become on the basis of what they played at their audition. The promise

was there, but not everyone could hear it, though some certainly could

detect it in hindsight. Asked by this author in 1985 whether he would

have turned down the Beatles, for instance, American producer Shel

Talmy—who was hired by Decca shortly after the Beatles’ audition and

(as an independent producer) went on to oversee hits by the Kinks, the

Who, and others—replied, “I don’t think I would have, because I’ve

always been very song-oriented. Although they were not a wonderful band

musically, the songs were outstanding, even then. And I’m sure I

wouldn’t have turned them down.”

One also wonders whether one little-documented

incident sealed Decca’s reservations about working with this unknown

provincial act. According to Pete Best’s autobiography, at one point in

the audition Epstein had the temerity to criticize something about

Lennon’s singing or guitar playing, upon which the Beatle burst into a

brief tantrum, raging at his manager, “You’ve got nothing to do with

the music! You go back and count your money, you Jewish git!” In

retrospect, it seems rather unlikely that either Epstein would say

something so bold to the volatile Lennon on such an important and tense

occasion, or that Lennon—who for all his volatility was fully aware of

what was hanging in the balance— would have jeopardized the Beatles’

chances with such an outburst. But then again, Pete Best was there, and

we weren’t. (As a bizarre footnote, incidentally, Best would actually

end up recording for Decca—with Mike Smith producing—as part of his

subsequent group, Lee Curtis & the All Stars, and as part of the

Pete Best Four on their June 1964 single “I’m Gonna Knock on Your

Door”/“Why Did I Fall in Love With You?” long after the Beatles had

started their run of hit records for EMI.)

For all the

bitter

disappointment of the Decca failure, the one thing the Beatles gained

from the association—the actual audition tapes— proved in some ways

quite useful, and would ironically in one small way help lead the band

to a recording contract soon enough. For Epstein got to keep the two

reel-to-reel audition tapes, which he took to play when he tried to

shop the group around to other labels in early February. The manager of

the HMV record store on London’s main shopping strip, Oxford Street,

suggested to Brian that it would be better to press the tapes onto

discs rather than hauling around the less instantly playable

reel-to-reels. Epstein took up the suggestion immediately, going right

into a studio above the store where demos could be pressed.

As engineer Jim Foy was making the discs, he told

Epstein that the Beatles sounded good. Epstein told him that three of

the songs were group originals, and Foy got Sid Coleman, who ran a

music publishing subsidiary of EMI (Ardmore & Beechwood) on the

store’s top floor, to give them a listen. Coleman liked those

rudimentary Lennon-McCartney songs enough to talk about a publishing

deal with Epstein there and then. Brian didn’t take him up on that at

the moment, as getting a recording contract was his most urgent

mission. To help him out in that regard, Coleman called George Martin,

the head of A&R at Parlophone, a subsidiary of EMI. That led to a

meeting between Epstein and Martin, who in turn was interested enough

in what he heard on the discs to—after another tangled sequence of

events beyond the scope of this book—offer the Beatles a recording

contract later in 1962. His decision wasn’t based wholly on the Decca

tapes; he auditioned the band at EMI himself in June 1962. Discussing

the Decca tapes in a 1971 Melody

Maker interview, he even clarified, “I wasn’t knocked out at all,

in defense of all those people who turned it down it was a pretty lousy

tape, recorded in a back room, very badly balanced, not very good

songs, and a rather raw group. But . . . I thought they were

interesting enough to bring down for a test.” So those tapes had

indirectly led Epstein and the Beatles to Martin, the producer of

almost everything the band recorded in the studio.

When the EMI deal was sealed, there seemed to be no more use for the Decca tapes. But although there was virtually no interest in or market for bootlegs of unreleased rock music at the time, it seems that the material almost immediately began to circulate outside the hands of Epstein or the labels with whom he’d been dealing. According to Hans Olof Gottfriddson’s The Beatles from Cavern to Star-Club, in the spring of 1962 the group gave a tape of eight of the tracks to their close friend Astrid Kirchherr, who gave it to a friend of hers a year later. It still seems unlikely many people heard any of this material beyond a very select few before 1977, when—according to Clinton Heylin’s Bootleg: The Secret History of the Other Recording Industry—the complete tape was acquired for $5,000 by a couple of New Yorkers. Immediately they began to leak it out on bootleg, though the way the songs were spread out over several releases (including a series of colored vinyl 45 picture sleeve singles) frustrated those who just wanted to hear all 15 tracks in one go. Indeed, it didn’t take long for some of the tracks to actually get broadcast on commercial radio; the author remembers hearing a few on a Beatles “A–Z” weekend on an FM station in Philadelphia in the late ’70s, for instance.

It also didn’t take long for everything to get assembled on a single bootleg LP, The Decca Tapes, complete with extensive liner notes comprised of a fanciful piece of historical fiction by one “Grid Leek.” The no doubt pseudonymous Mr. Leek wrote about the songs as if ten of them had been released on five 1962 Decca singles preceding their deal with Parlophone, and four of the others on two post-Parlophone-signing Decca 45s that were soon withdrawn from the market, with “Take Good Care of My Baby” an outtake “which was only recently retrieved from the Decca vaults.” As tongue-in-cheek as it was, the packaging—complete with an excellent picture of the leather-clad Pete Best lineup on the cover—was vastly better than the remarkably shabby treatment much of the material got when it was issued by Phoenix Records in the US on the semi-official LPs The Silver Beatles Vols. 1 & 2 in September 1982. As if the ugly nondescript sleeve graphics weren’t bad enough, several of the tracks were mastered at the wrong speed, and half of them were lengthened artificially by editing and splicing. In 1988, the surviving Beatles finally sued the companies responsible for issuing this material in the US and UK, forcing them to take it off the market.

The Silver Beatles Vols. 1 & 2

had actually contained all of the songs (albeit sometimes in butchered

form) from the Decca tapes except “Love of the Loved,” “Like Dreamers

Do,” and “Hello Little Girl,” perhaps because these gray-market labels

didn’t want to deal with any complications ensuing from issuing songs

with Lennon-McCartney copyrights. They were so poorly distributed (and

packaged), however, that the vast majority of listeners from the

general public still had not heard any of the Decca tapes before five of

the tracks were included on Anthology

1. Most Beatles fans still have yet to hear any of the other ten

tracks, although they’re perennials on uncounted bootlegs to the

present day. Anyone willing to look just a little bit further than

conventional record stores can find all 15 cuts, to be frank. But as one

of the very most important groups of unreleased Beatles recordings, as

well as a crucial document of the early days of the best band there

ever was, the Decca audition deserves official release, with the kind of

historically minded packaging it merits.

There are a couple of semimyths surrounding the

Decca tapes, oft-repeated in books and articles about the Beatles, that

bear serious reinvestigation and reassessment. One is the claim that

Brian Epstein sabotaged the group’s chances by selecting the songs they

were to play at the audition, weighting them too heavily toward

lightweight pop material that was neither suited for their strengths

nor typical of what they liked or played onstage. It’s probable that

Epstein did have significant input into the song list, and it also seems

likely that he was the force who pushed for the most pop-oriented tune,

“September in the Rain”; he’d cited Dinah Washington’s version as one

of ten favorite records of 1961 in Mersey

Beat. As a result of Epstein’s blunder, the speculation goes,

not only did Decca turn the band down, but the Beatles insisted that he

never have anything to do with their musical policy again. Boyhood

Beatles friend (and future longtime personal assistant to the group)

Tony Bramwell writes in his recent memoir Magical Mystery Tours: My Life with the

Beatles (co-written with Rosemary Kingsland), for instance, that

“Paul did ‘Besame Mucho’ at Brian’s insistence. He muttered that it was

a silly ballad. ‘We should have just done our own stuff,’ he said.”

Remarked Mike Smith on the Best of the Beatles DVD, “Some of

the songs, they were really strange choices. The ones that I remembered

had to be ‘Sheik of Araby’ and ‘Three Cool Cats.’ It may well be that I

remember them because they were just sort of totally foreign to

everything that they did afterwards. I may have interpreted it wrongly,

but my take on auditions at that time was, you let the people do what

they want to do. Because that’s what they think represents them in the

best possible light. And as it transpired, it wasn’t the case. They

weren’t playing the songs that they thought portrayed themselves in

their best light. They were probably very pissed off at having to

do—well, I certainly would have been—at some of the stuff that they had

to do.”

In actual fact, however, the 15 songs performed for Decca are a fairly well-rounded sample of the material the Beatles were doing at the end of 1961, and on the whole pretty accurately reflect their tastes and eclecticism. There seems little question that the group, and particularly Lennon and McCartney, would be eager to present the best of their original material. They didn’t play more original songs, most likely, because their live set was still almost wholly devoted to covers, and because they didn’t have a whole lot of songs that would have impressed major label A&R men, with even most of the compositions they cut for EMI in 1962 and 1963 having yet to be written. As for the covers, it’s simply absurd to suggest that any of them, aside from perhaps “September in the Rain,” were done under duress. Not only did the Beatles actually record “Money” and “Till There Was You” again in 1963 for their second album, but they also later did “To Know Her Is to Love Her,”“Memphis, Tennessee,” “Sure to Fall,” “Crying Waiting, Hoping,” “Besame Mucho,” and “Three Cool Cats” for the BBC (though their January 1963 and July 1963 BBC versions of “Three Cool Cats” weren’t broadcast and, sadly, no tapes of those versions survive). They also did “Besame Mucho” and “To Know Her Is to Love Her” on their December 1962 Hamburg tapes. Certainly they wouldn’t have revisited them if they had any dislike for the material.

What’s more, they

did one

of the less rock-oriented songs, “Besame Mucho,” again at their EMI

audition for George Martin in June 1962, indicating that either Epstein

was still pushing for them to play standards or (far more likely) that

the Beatles really enjoyed doing the number. If the group was truly

resolved not to let Epstein pressure them into playing prewar pop

standards like “September in the Rain” at future auditions, it’s odd

indeed that the list of songs Brian sent to Martin shortly before their

EMI session (as suggestions for what he should hear) included not just

“Besame Mucho,” but also numbers like “Over the Rainbow” and Fats

Waller’s “Your Feet’s Too Big” (both to be sung by Paul), and—again—

“September in the Rain,” “Sheik of Araby,” and “Take Good Care of My

Baby.” In fact, this list (numbering 33 tunes in all) contained no less

than ten of the same songs that had already been auditioned at Decca,

with “Three Cool Cats,” “Till There Was You,” “To Know Her Is to Love

Her,” “Memphis, Tennessee,” and all three Lennon-McCartney songs also

reappearing. It wasn’t a substantially different setlist than what had

been played at Decca, though it was much longer. Either there was some

major miscommunication going on between Epstein and the band, or, as

seems evident, the more pop-inclined material was genuinely a part of

their repertoire and influences, though just one part.

In truth, the majority of the Decca audition was

devoted to the pure and hard American rock ’n’ roll the Beatles loved

most, from both the black and white spectrums. There was early Motown

(“Money”), the black vocal group sound of the Coasters, rockabilly

(Carl Perkins and Buddy Holly), Chuck Berry, and even Phil Spectorized

doo wop (“To Know Her Is to Love Her”). Plus there were a few of their

own compositions, a privilege that many of the managers of the time

would have denied their clients of playing at an audition for one of

the biggest record labels in the country. Decca did not turn down the

Beatles because the material it heard was misleading or

unrepresentative of the band. The company turned them down, rightly or

wrongly, because it didn’t like how they played it.

There’s also the matter of whether it was really

that big a disaster, for either Decca or the Beatles, that they didn’t

pass the audition. Ironically, Decca would sign the second biggest

British ’60s rock band the following year, after a chance spring 1963

meeting between George Harrison and Dick Rowe when they were judges at

a talent competition in Liverpool. Harrison, according to Rowe,

admitted that Decca was right to have turned the Beatles down, and that

they hadn’t played that well at the audition. (Of course, Harrison no

doubt felt better about it now that the Beatles had already started to

sell massive amounts of singles and albums for EMI.) George told the

A&R man that he should check out a new London band that Harrison

had just seen, the Rolling Stones—whom Decca quickly signed. Decca

continued to sell loads of records throughout the 1960s, often by the

very sort of rock groups they’d prophesized were on their way out when

they turned down the Beatles. There’s even been some speculation that

the label overcompensated for its missed opportunity to nab the Beatles

by signing as many bands as it could, many of whom wouldn’t pan out or

make the slightest impression on the charts (though Decca still managed

to turn down Manfred Mann and the Yardbirds shortly after the Beatles

rose to stardom).

As for the Beatles, as heartbroken as they must have

been when the word came down from Decca in February 1962, was it really

that bad a thing in the long run? Had they done the deal, they’d have

been recording with drummer Pete Best, unless Decca, like George Martin

a bit later, planned to replace him on recording dates with a session

man. That would not only have been a musical liability, but it might

have been harder to replace Best with the more talented and personally

compatible Ringo Starr if the band had already started to release

records. Plus the group wouldn’t have had as much original material

ready for release, and what material they had wouldn’t have been nearly

as good as what they were coming up with within a year. It’s also often

overlooked that the Beatles really weren’t as good in January 1962 as

they were even six months later, and certainly a year later. There’s

truly an enormous distance between the Decca tapes and their first

album, Please Please Me,

which, like the Decca audition, was (with the exception of four songs)

recorded in a single day, in February 1963. Simply put, they were

writing, singing, and playing a lot better (and with the right drummer)

by the time they made their first big hit records, and benefited

enormously from the wait, as brief and enforced as it was.

And, most importantly, they would not have been

working with George Martin—probably the best producer imaginable for

the Beatles, not only in 1962, but from 1962 until the band split

up in 1970. Had they been on Decca, it’s easy to imagine that they

might have been paired with an unsympathetic or unimaginative

production team that could have forced them to record inappropriate

material, not allowed them to record their own songs, or simply not

gotten the best out of them in the studio. For all the regret he

subsequently expressed over rejecting the group, Mike Smith was

probably not the man to be in charge, given that he actually told the

Beatles fan magazine The Beatles Book

that Pete Best “was a better drummer than Ringo.” (This in turn

illustrated his assertion in Drummed

Out! The Sacking of Pete Best that “I don’t think I could have

worked with them the way that George Martin did—I would have got

involved in their bad parts and not encouraged the good ones.”) Had any

or all of this been the case, it’s easy to imagine the Beatles failing

to make much of a commercial impact with Decca, and to even envision

the band breaking up in discouragement before their art had truly been

allowed to bloom.

When the Beatles were rejected by Decca they must

have felt it was the worst thing that could have possibly happened to

them. But time proved that it was one of the best breaks they ever got.

HOME WHAT'S NEW MUSIC BOOKS MUSIC REVIEWS TRAVEL BOOKS