SECOND

DEGREES OF VU SEPARATION

Although the Velvet Underground are sometimes portrayed as existing in

near-total-obscurity totally out of the mainstream of 1960s rock

culture, in fact they intersected with—and sometimes even

influenced—many major shakers and movers between 1965 and 1970.

Starting with the most famous rock group of all, some of them include:

The Beatles: Brian Epstein,

manager of the Beatles, liked the Velvet Underground's first album and

was considering getting involved with them in some capacity in 1967.

This might have entailed helping arrange for some VU gigs in Britain

and Europe—something the Velvets had several opportunities to do while

Lou Reed was in the band, but unfortunately something that never came

to pass. VU manager Steve Sesnick also tried to interest Epstein in

making a publishing deal for the Velvets' songs. But the Velvet

Underground decide to hang onto their publishing, and in any case

Epstein died on August 27, 1967.

In a semicomic incident, Lou Reed himself met Brian Epstein around

spring 1967 when, at publicist Danny Fields's instigation, Reed

finagled a cab ride with the Beatles manager in New York in the hopes

that some interest in the VU's affairs might be ignited. Evidently

nothing came of it, however, other than Epstein sharing a joint with

Reed and telling Lou how much he liked the banana album.

In Richard Witts's biography Nico:

The Life & Lies of an Icon, she claims to have been in

attendance at the private party Brian Epstein threw at his home on May

19 to preview the Beatles' Sgt.

Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band for the press. "There is a song

I liked on Sgt. Pepper,

called 'A Day in the Life,'" she states in the book. "It has a

beautiful song and then this strange sound like John Cale would make

(he told me it was an orchestra, actually) and then this stupid little

pop song that spoils everything so far. I told this to Paul

[McCartney], and I made a mistake, because the beautiful song was

written by John Lennon and the stupid song was written by Paul. It can

be embarrassing when you speak the truth." The book also reports that

she briefly stays in Paul McCartney's home during that May visit.

The Rolling Stones: Quite heavy

connections were laid between the Stones and the Velvets, albeit mostly

via Nico, who met Brian Jones in March 1965 and had a brief affair with

him. Rolling Stones manager/producer Andrew Oldham arranged for her to

put out her sole pre-VU single, "I'm Not Sayin'"/"The Last Mile," on

his Immediate label in the UK that summer. Jones played guitar on the

single, and later that year, before the VU had met Nico, briefly met

John Cale in New York when Cale somehow managed to get a limousine ride

with him and Carole King. Nico would later accompany Brian Jones to the

Monterey Pop Festival in June 1967, where Jones introduced Jimi Hendrix

at his first major American concert.

Of perhaps more note is that the Velvet Underground are confirmed to

have directly influenced an actual well-known late 1960s Rolling Stones

recording. As Mick Jagger confessed to Nick Kent of NME in June 1977, "Even we've been

influenced by the Velvet Underground. No, really. I'll tell you exactly

what we pinched from [Lou Reed]. Y'know 'Stray Cat Blues' [from the

Rolling Stones' 1968 album Beggars

Banquet)? The whole sound and the way it's paced, we pinched

from the first Velvet Underground album. Y'know, the sound on 'Heroin.'

Honest to God, we did!"

Jim Morrison: The Doors' lead

singer and Nico had a serious and passionate affair around the summer

of 1967, though apparently not so serious that Morrison was tempted to

leave his primary girlfriend of the last five years of his life, Pamela

Courson. More importantly, Morrison was the single biggest influence in

inspiring Nico to begin writing her own songs (as well as in her

decision to dye her hair red, knowing how much he liked the redheaded

Courson).

Eye magazine, revealed Danny

Fields in the 1970 book Age of Rock 2,

took his suggestion to set up a photo shoot with Nico and Jim Morrison

for "a series on beautiful couples...But Morrison refused to do it, and

he was angered and he said don't ever do that without asking me about

it first. He was really pissed at me, and Nico was hurt that he didn't

want to pose with her...But you just don't tell him what to do." (One

would think that Jim might also be wary of angering his volatile core

girlfriend, Pamela Courson, with such a public posed picture of himself

with another beautiful woman.) Ex-UCLA film student Morrison, added

Fields in the same interview, "said that someday he would do a movie

and Nico would be in it, but he wasn't going to have his picture taken

with her for Eye magazine"—and, as it turns out, he never did that

movie with Nico either, though apparently it was hoped that he'd appear

with her in the 1967 Andy Warhol movie I, a Man.

Prior to this, Morrison had seen the Velvet Underground at their first

California shows at the Trip in Los Angeles in May 1966, a gig at which

the then-unsigned Doors might have played some shows as the support act

if the engagement hadn't been canceled after a few days. Some have

speculated that the dress and image of one of the Exploding Plastic

Inevitable's dancers, Gerard Malanga, influenced Morrison's own

appearance as Doors frontman. Morrison also attended a couple of the

Velvet Undergrond's shows at the Whisky-A-Go-Go in Los Angeles in late

October 1968 with his actor friend who'd ended up playing alongside

Nico (and several other women) in I,

a Man, Tom Baker.

To dispel a mini-myth, the television documentary Rock & Roll, widely screened on

both the BBC in the UK and PBS in the US, is almost certainly mistaken

when its narrator solemnly asserts that Jim Morrison, "a young film

student, had seen [the Velvet Underground] in San Francisco and was

inspired to start writing songs himself with his band the Doors."

First, the notion that the Velvets inspired him to start writing songs

is laughable; when the Doors formed back in the summer of 1965,

Morrison had already written the backbones of several songs the Doors

would record on their early albums, and in fact decided at that time to

form the band with keyboardist Ray Manzarek after singing one of them,

"Moonlight Drive," to him on a Los Angeles beach. And on the weekend of

May 27-29 (the only time the Velvets played San Francisco, at the

Fillmore, before the Doors recorded their first album), Morrison was

almost certainly not in San Francisco, as the Doors were in the midst

of the first week of a residency at the Whisky-A-Go-Go in Los Angeles—a

residency they'd been dying to get.

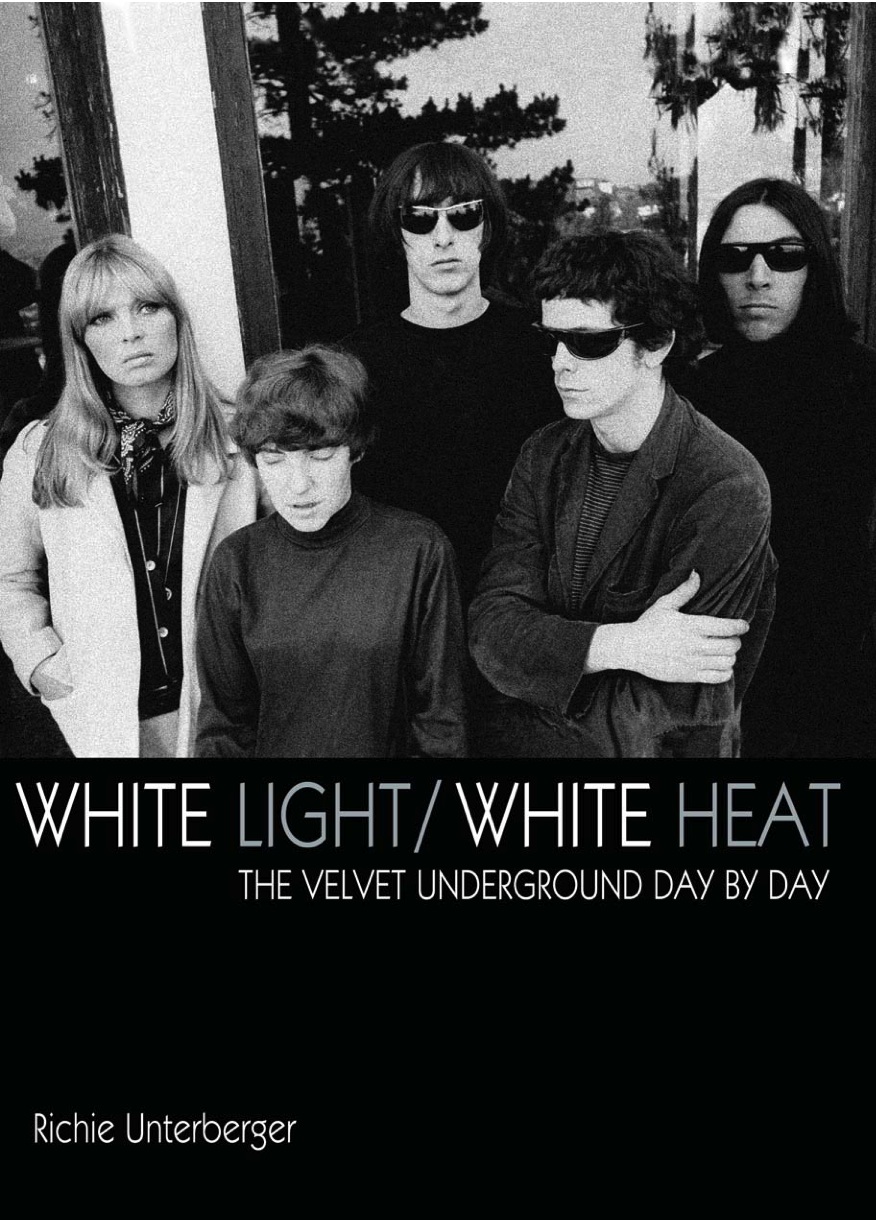

"The VU influenced the Doors?" said Ray Manzarek when interviewed for White Light/White Heat: The Velvet

Underground Day By Day. "How? Musically? No chance. They

couldn't play. We were working John Coltrane modal territory. Miles

Davis was our influence. Lou Reed influence Jim? Lyrically? Jim was

coming from a point of cosmic consciousness. Carl Jung. Friedrich

Nietzsche. Lou was New York street hustler punk. Great, but not

Morrison. No way. They did have a nice junkie rush, however. I liked

that. A punk band before its time." And as Ray also confirmed, "Jim

liked Lou Reed's lyrics a lot. Dark, New York, gay and junkie. Almost

like John Rechy in City of Night"—the

1963 novel whose title the Doors would use as a key lyric of their

classic "L.A. Woman."

Bob Dylan: Dylan had a brief

affair with Nico in Europe in the spring of 1964, during which, she

later claimed, he wrote the song "I'll Keep It with Mine" about her and

her small son. She caught up with him again in London about a year

later, and can be seen talking with Dylan's manager Albert Grossman in

outtakes from the Dylan documentary Dont

Look Back issued as part of the Dont Look Back 65 Tour Deluxe Edition

DVD in 2007. Around that time Dylan, after some pestering from Nico,

did a one-take piano demo of "I'll Keep It with Mine" at an unspecified

London studio. The recording was pressed onto an acetate demo that's

probably the one Nico later remembers (in What Goes On #3) as having been

"sent" to her by Dylan "because he had promised me a song for my

singing," though maybe it was simply given to her right after it was

cut.

In a 1986 interview with Melbourne radio station 3RRR-FM, Nico claimed

that Albert Grossman "bought me a ticket and said I should come over

[to New York], that he can only do something for me over there." If

that's the case, however, a management agreement between her and

Grossman never seemed to solidify after she arrived in the city in late

1965. She remained determine to record "I'll Keep It with Mine,"

though, even though Judy Collins beat her to the marketplace with a

version of a song on a mid-'60s single (Dylan not releasing a version

of his own in the '60s). She even sang it at some early Velvet

Underground performances, over the reluctance of the group, who didn't

like the song or want to do outside material in general. She finally

did get it on record on her first album, 1967's Chelsea Girl.

From the first known recording of "Heroin" (a May 11, 1965 demo that

still hasn't been bootlegged) and the July 1965 VU demos that appear on

the Peel Slowly and See box

set, it seems apparent that Lou Reed was noticeably influenced by

Dylan's singing (and, in the July 1965 demo "Prominent Men,"

songwriting) in his early days, though that influence would soon

disappear. It's not known if Dylan heard or even had an opinion about

the Velvet Underground, however. It's certainly unlikely, as the Rutgers Daily Targum claimed on

March 2, 1966, that "Bob Dylan may be in the audience" (at a show at

Rutgers University the following week), and even less so that "Dylan

and the Velvets attend each others' concerts," as the article also

reported.

The Yardbirds: Though actual

personal interaction between the bands was probably slight, the

Yardbirds did share a bill with the Velvet Underground (and numerous

other bands) in Detroit on November 18-20, 1966. More interestingly,

the Yardbirds probably became the first big-name band to be influenced

by the Velvet Underground—at least to the extent that they became the

first such band to cover a Velvet Underground song—when they hear d"I'm

Waiting for the Man," purchasing the group's debut album soon after it

comes out in 1967, and even adding "I'm Waiting for the Man" to their

live repertoire.

"We heard it and thought, 'This is quite a good song, isn't it?'"

Yardbirds drummer Jim McCarty told Will Shade of Ugly Things magazine decades later.

"We probably did it because we were low on ideas and were looking

around for material. We played it with the Jimmy [Page] lineup." Adds

Yardbirds bassist/guitarist Chris Dreja in the same interview, "We did

that very occasionally, when odd bits of material by other artists

showed up in our set. That actually might have been Jimmy who wanted to

do it. Good call on his part." A lo-fidelity but interesting tape

survives of them playing "I'm Waiting for the Man" (albeit segueing in

and out of "Smokestack Lightning") at one of their final shows, at the

Shrine Hall Exposition in Los Angeles on May 31, 1968.

David Bowie: Bowie did not have

his first hit single in the UK until 1969 (and did not become popular

in the US until three or four years after that), and didn't meet any of

the Velvets until 1971. But there can be no doubt that Bowie was the

first rock star to count the Velvet Underground as a major influence,

and that he in turn did more than any other early-'70s rock star to

popularize the group and their material. It's not as commonly known

that Bowie was actually one of the first British residents of any sort

to hear the Velvet Underground after his manager of the time, Kenneth

Pitt, brought him back an acetate of the banana album after a visit to

New York in late 1966. Bowie became an immediate fan of the album,

putting "I'm Waiting for the Man" into his live set within months. He

even recordied an outtake on April 5, 1967 (since frequently

bootlegged), "Little Toy Soldier," which lifts some lines from "Venus

in Furs" word for word. An outtake of "I'm Waiting for the Man" might

date from this session as well, and Bowie went on to perform "I'm

Waiting for the Man" and "White Light/White Heat" on the BBC in the

early 1970s, as well as write "Some V.U., White Light returned with

thanks" next to "Queen Bitch" on his handwritten track list on the back

cover of his 1971 LP Hunky Dory.

By the following year, of course, he was instrumental in helping to

launch Lou Reed's solo career as co-producer of Reed's Transformer album.

The only time Bowie saw the Velvet Underground, however, was in early

1971, by which time Reed had left the band. Sometime during the VU's

two-night stint at the Electric Circus on January 29 and January 30,

the Velvets were paid a surprise visit by the up-and-coming star,

though the ensuing ghoulish case of mistaken identity makes it hard to

know whether to laugh or cry. "I remember this English kid coming

backstage, and I was holding forth as if I was somebody, feeling very

self-important as the leader of this band," Doug Yule told Record Collector in September 2001.

"He came in, and obviously assumed I was Lou Reed, and so I had to

explain that Lou wasn't there. It was only a few years ago that I heard

the story back from someone else, and realized that the English kid was

David Bowie. In 1971, I'd never heard of him!"

Pink Floyd: It's not known

whether Pink Floyd heard the Velvet Underground in the 1960s, and very

doubtful that they actually met them. But the Velvets certainly came to

the attention of Peter Jenner, who co-managed Pink Floyd from around

mid-1966 to early 1968. After hearing some unreleased Velvet

Underground demos that were circulating in London (and almost certainly

predated the banana LP sessions), Jenner was intrigued enough to call

John Cale in the US with an eye to managing the group. Laughed Peter in

his interview for White Light/White

Heat: The Velvet Underground Day By Day, "He told me to fuck

off, I think, in a very nice way. 'That's alright —we have someone who

does that for us,' you know. I think Cale said something about how they

were with Andy Warhol, and I'd heard of Andy Warhol, so I was very

impressed. 'Oh wow, they're okay, that's a shame, next please'—I mean,

it was as short as that. It was a very short conversation, 'cause back

in those days, Transatlantic phone calls were very expensive. John Cale

was very pleasant to me in a so-slightly patronizing way, which is

fine. It's what I deserved. It was a real amateur hour approach."

Jackson Browne: The man who

epitomized the 1970s Southern Californian singer-songwriter genre is

one of the least likely guys you'd associate with the Velvet

Underground in their prime. Yet in early 1967, the still-teenaged and

unsigned Browne was for a brief period not only Nico's guitarist and

supporting act for weeks during her long-running stint at the Dom club

in New York, but also her boyfriend. Still technically in the Velvet

Underground at that point, Nico began to record her debut solo album, Chelsea Girl, early that spring,

which included three songs that Browne wrote or co-wrote, Jackson also

helping out on guitar. After the session on which he played, he went

with Lou Reed to see the Murray the K Show rock revue in New York,

which featured Cream, the Blues Project, Jim and Jean, and Wilson

Pickett.

Michelangelo Antonioni: The

great Italian film director expressed interest in featuring the Velvet

Underground in the club scene in his classic 1966 movie Blow-Up, shot in London. It's not

certain that the Velvets would have been in the film even had they

agreed to the proposition, since it's known that Antonioni also made

overtures to at least three other British bands (the Who, the

Yardbirds, and Tomorrow). It ended up being the Yardbirds, in their

lineup with both Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page as guitarists, who played the

scene, Beck famously smashing his guitar onscreen. According to

Sterling Morrison, although the Velvets were willing to take the role,

the plan fell through due to a combination of visa/work permit problems

and the expense of bringing the group and their entourage to England.

Federico Fellini: More than six

years before joining the Velvet Underground, Nico took a small but

memorable role in what's probably the Italian director's greatest and

most famous film, La Dolce Vita.

In spite of a lengthy musical career that lasted from the mid-1960s to

the late 1980s, this role remains what she's most famous for to the

general public.

Serge Gainsbourg: One of the

giants of twentieth-century French pop music, and now with an expanding

international cult, Gainsbourg too had a fleeting association with Nico

when he recorded a demo tape for Philips Records around late 1962 of

her singing "Strip-Tease." This was the theme song he co-wrote for the

movie of the same name, with Nico's only starring role in an

aboveground commercial film. Still unknown even to many Velvet

Underground fans, the demo—Nico's only known pre-1965 recording—finally

surfaced on the three-CD Gainsbourg box set Musiques de Films 1959-1990, issued

by Universal in France in 2001.

John Cage: One of the giants of

twentieth-century avant-garde music had his own pre-VU moment when John

Cale was one of the pianists at a performance of 840 consecutive

renditions of Erik Satie's "Vexations." Organized and overseen by Cage,

this took place at the Pocket Theater in New York on September 9-10,

1963. A photo of Cale playing piano at the event appeared in the New York Times, marking his greatest media exposure in the

1960s, the Velvet Underground years included.

Terry Riley: One of the most

acclaimed contemporary composers replaced Cale in La Monte Young's

group in late 1965, and went on to collaborate with John on the 1971

album credited to both of them, Church

of Anthrax.

Jimi Hendrix: Hendrix saw the

Velvet Underground at one of their shows at the Whisky A Go Go in late

October 1968. He told the band afterward, as Doug Yule recalled in a

1996 issue of the fanzine The Velvet

Underground, that "he loved the music and the energy." Hendrix

was in Los Angeles recording at T.T.G. Studios, the same facility the

Velvets would soon be using to record their third album, and it might

also have been around this time that Jimi "expressed disbelief to us

that we weren't bigger than we were," as Sterling Morrison remembered

in the BBC Curious

documentary. Hendrix and the VU also crossed paths at sessions at the

Record Plant studio in New York, which both artists used in 1969.

Frank Zappa & the Mothers of

Invention: Apparently these weren't pleasant interactions; see

another page on this website, "What Really Goes On: 22 Myths and

Legends about the Velvet Underground that White Light/White Heat: The Velvet

Underground Day By Day investigates, explodes, and clarifies,"

for a fuller rundown on the Mothers-VU rivalry. Still, it's worth

noting that the Velvets and Mothers played together on bills in both

Los Angeles and San Francisco at the VU's first California shows in May

1966, at a time when both acts had just been signed to Verve Records,

and neither had released their first discs.

John Cale later remembered Zappa putting down the Velvet Underground

onstage in Los Angeles, igniting an almost inexplicable long-running

animosity of sorts between Zappa and the Velvets. "I don't remember him

actually putting them down onstage, but he might have," said Mothers of

Invention drummer Jimmy Carl Black in his interview for White Light/White Heat: The Velvet

Underground Day By Day. "He really disliked the band. For what

reasons I really don't know, except that they were junkies and Frank

just couldn't tolerate any kind of drugs."

Black also emphasized, "I know that I didn't feel that way and neither

did the rest of the Mothers. I thought that they were very good,

especially Nico (whom I secretly fell in love with, or was it lust). I

especially thought that Moe was a very good drummer, because in those

days I don't recall there being any other female drummers on the

scene." Yet, he concedes, "the thinking of the audiences was completely

different than those from New York City. They were lukewarmly received."

Bill Graham: The Velvet

Underground's experiences with the most famous American rock promoter

were yet less pleasant, and the group never worked with him after some

shows in late May 1966 at the Fillmore in San Francisco. The dislike

the Velvets and their entourage had for Graham has been expressed in

numerous sources. For his part, Graham had this to say in the March 10,

1968 Los Angeles Times. "A

prime example of my bringing in something I don't like was the Andy

Warhol show," he told Leonard Feather. "I thought it was important that

if anything has that much notoriety, it should be exposed for what it

is. Notified the press in front that I was doing it for just that

purpose. So he brought in the show, with the Velvet Underground and the

film with the perverted scene and the whole bit; the worst piece of

entertainment I've ever seen in my life. It was supposedly geared

toward the concept of what's happening to youth today; but when you

looked at it, what was it? Negativism. Everything was anti. It was

sickening, and it drew a real Perversion U.S.A. element to the

auditorium. The only thing that saved the day was, I brought in the

Mothers of Invention, for protection."

Added Graham, "In itself the Warhol thing made a great point, because

it really showed what I wanted to say. 'Look, America, look what you've

chosen as your artistic hero.' Sure, we made a lot of money, but at the

end of the show, in answer to the question 'when do you want to have us

back?,' I simply told Mr. Warhol that I never wanted to see him in the

auditorium again."

For their part, some of the Velvets and their associates felt that

Graham's light show of the time was laughably primitive, and that he

subsequently put some of their ideas in that regard to use in the shows

he presented over the next few years. Doug Yule remembers this being

discussed within the band even after he joined in late 1968, more than

two years after the concerts. "This is one of Sterling's rants that he

would go on: they felt that when they showed up with the Exploding

Plastic Inevitable that Graham was doing like kindergarten-level light

shows, and they kind of opened his eyes and then he ripped 'em all off,

took all our ideas and put that out as his own," he said in his

interview for White Light/White

Heat: The Velvet Underground Day By Day. "Which always seemed to

me kind of like sour grapes. But there was that element; that was

something that was talked about from time to time."

Betsey Johnson: A classmate of

Lou Reed's at Syracuse University, she designed clothes for the Velvet

Underground and married John Cale in 1968 (divorcing him a few years

later). She later became, and today remains, one of the most famous

fashion designers in the world.

Marianne Faithfull: On a visit

to London in 1965, John Cale managed to get a copy of Velvet

Underground demos into the hands of Marianne Faithfull. The hope was

that she'd pass it to Mick Jagger, with whom she had shared

manager-producer Andrew Loog Oldham, and who was producing Nico's first

single in London this very summer. But Faithfull closed her door

without even letting John inside.

Jimmy Page: In addition to

playing "I'm Waiting for the Man" live while he was with the Yardbirds,

Page co-wrote (with Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham),

produced, and played guitar on "The Last Mile," the B-side of Nico's

1965 single. Nico was dismissive of the effort in retrospect,

commenting in a 1979 interview published in Kristine McKenna's Book of Changes anthology, "I made

a single once with Jimmy Page but it was a failure both artistically

and commercially. Page's music was like cement."

Tim Buckley: Briefly backed

Nico on guitar during her residency at the Dom in New York in early

1967, at which he also served as her supporting act for a similarly

brief period.

Tim Hardin: Reported to have

briefly backed Nico on guitar during her residency at the Dom in New

York.

Ramblin' Jack Elliott: Reported

to have briefly backed Nico on guitar during her residency at the Dom

in New York.

Leonard Cohen: Infatuated with

Nico in the late 1960s, he saw many of her early solo appearances. Nico

is reported to have been at least part of the inspiration for his songs

"Memories," "Take This Longing," and "Joan of Arc." Cohen also met Lou

Reed around this time, and was pleasantly surprised to find that Lou

already had a collection of his poems, Flowers to Hitler, that had yet

to be published in the United States. Reed asked Leonard to sign his

copy, and also played some of his own songs to Cohen, who liked them

very much.

Elton John: Well known as a

longtime fanatical record collector, Elton John was likely one of the

earliest British stars to hear and appreciate the Velvet Underground.

On January 2, 1971, just as he was starting to emerge as a star

singer-songwriter, he was the guest for Melody Maker's "Blind Date" column,

which played tracks to celebrity musicians and asked them to identify

and comment upon the songs. John immediately guessed that it was the

Velvet Underground when he was played "Rock & Roll," even though

Loaded wouldn't be out in the UK for a couple months. "Great

album...the best I heard in the States," he enthused. "I've never been

a Velvet Underground freak, so it was something of a surprise to me.

It's just a simple, relaxed album. They're a strange band, too...they

made this album and apparently disappeared."

Robbie Robertson: The future

Band guitarist, then recently enlisted to be (with other future Band

members) part of Bob Dylan's backup group, checked out the then-unknown

Velvet Underground in late 1965 at the behest of the group's manager of

sorts at the time, Al Aronowitz. Robertson, never one for far-out

sounds, left after just one song, exclaiming to Aronowitz, "I can't

take no more a [sic] this!"

Mick Farren: In the 1960s, the

future top rock critic and, these days, prolific novelist and author

was singer in London underground band the Deviants. After managing to

hear unreleased pre-banana album demos that were circulating in London,

the Deviants probably became the first band to cover Velvet Underground

songs in concert.

Buffalo Springfield: Not the

first major '60s rock group you'd think to associate with the Velvet

Underground. But in May 1966, Sterling Morrison—bored with staying at

the Castle, the home that had been rented for the Velvets for their

trip to Los Angeles—moved to the Tropicana hotel near Sunset Strip,

where he partied with members of the Springfield.

The Grateful Dead: Though

probably considered the ultimate antithesis to the Velvet Underground

among major 1960s rock bands, there were tenuous connections between

the VU and the Dead. Hetty MacLise, wife of original Velvet Underground

drummer Angus MacLise, was briefly a girlfriend of the Grateful Dead's

Pigpen, and, in an interview with the fanzine Bananafish, remembered playing

tanpura on the Dead's version of "Dark Star" that was released as a 45

in 1968. The Dead and the Velvets also shared the same bill not just

once, but twice, in 1969. Coincidentally, both groups also used the

name "the Warlocks" before settling on different ones.

Loudon Wainwright III: It was

with singer-songwriter Wainwright -- then yet to release a record --

that original Velvet Underground drummer Angus MacLise and his wife,

Hetty MacLise, were busted for marijuana possession during a

cross-country drive in spring 1968.

Lincoln Swados: A paranoid

schizophrenic widely known in the Lower East Side for playing music in

the streets for many years before his death in 1989. In the early

1960s, he was Lou Reed's roommate at Syracuse University. Lincoln is

written about extensively in The

Four of Us: The Story of a Family, the memoir of his sister

Elizabeth, a famous composer of musicals, with 1978's Runaways getting

nominated for five Tony Awards; she'd later collaborate on musicals

with Doonesbury cartoonist

Garry Trudeau. Lincoln's travails are later reported to have inspired

songs on Reed's 1983 solo album Legendary

Hearts ("Home of the Brave") and his 1992 album Magic and Loss ("Harry's

Circumcision," as verified by an interview in the press kit for that

record).

Vaclav Havel: In April 1968,

the Czech playwright attended the English-language premiere of his play

The Memorandum at the Public

Theater in New York. During his six-week visit to the city, he was

urged by a Czech-American friend to buy White Light/White Heat or The Velvet Underground & Nico

(the specific album cited has varied according to the account).

Whichever LP or LPs were purchased, Havel did so, and became a fan of

the group. He remained one over the course of the next two decades,

during which time he also became involved with the dissident human

rights organization Charter 77, formed in his native country after the

jailing of musicians from the VU-inspired Plastic People of the

Universe in the mid-1970s. By the late 1980s, he and the movement were

instrumental in restoring democracy to the Czech Republic. The

nonviolent transition was, not coincidentally, dubbed the Velvet

Revolution, with Havel becoming the country's first post-Communist era

president on December 29, 1989.

Major musicians with whom the Velvet

Underground shared bills from 1965-1970: Charles Larkey (of the

Myddle Class, later husband of and collaborator with Carole King); Dave

Palmer (of the Myddle Class, later singer with Steely Dan); the Fugs;

the Mothers of Invention; the Yardbirds; Larry Coryell (as guitarist in

the Free Spirits); Chris Stein (later of Blondie); the United States of

America; Peter Wolf (later of the J. Geils Band); the Chambers

Brothers; Dr. John; the Electric Flag; Iron Butterfly; Quicksilver

Messenger Service; Sly & the Family Stone; the Paul Butterfield

Blues Band; the Rockets (later to evolve into Crazy Horse); Tim

Buckley; the Nazz (with Todd Rundgren); Chicago (then known as the

Chicago Transit Authority); the Sir Douglas Quintet; the Flamin'

Groovies; Canned Heat; the MC5; the Holy Modal Rounders; the Grateful

Dead (twice!); Spirit; the Nice (with

Keith Emerson); Taj Mahal; the Allman Brothers; Van Morrison; Bobby

Blue Bland; Jonathan Richman.

Celebrities in the audience at Velvet

Underground concerts between 1965-1970 included: Robbie

Robertson; Ellen Goodman (later one of the nation's most popular

syndicated columnists); Salvador Dali; Robert Rauschenberg; Allen

Ginsberg; Frank Sinatra; Senator Robert F. Kennedy and his wife Ethel;

George Plimpton; film director Mike Nichols; Sonny & Cher; John

Phillips and Cass Elliot of the Mamas & the Papas; actor Ryan

O'Neal; Jim Morrison; actor Severn Darden; Stokely Carmichael; Lawrence

Kasdan (director of The Big Chill);

choreographer Merce Cunningham; New York Senator Jake Javits; David

Rockefeller Sr.; David Rockefeller Jr.; William Gibson; Jimi Hendrix;

Robert Quine; Chrissie Hynde; Jonathan Richman; Jim Carroll; Deborah

Harry.

unless otherwise specified.

HOME

WHAT'S NEW

MUSIC BOOKS

MUSIC REVIEWS TRAVEL

BOOKS

LINKS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SITE MAP

EMAIL RICHIE

BUY BOOKS