UN-SUNG

HEROES OF VELVET UNDERGROUND-DOM

Everyone with a significant interest in the Velvet Underground knows

the names of Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, Maureen Tucker,

Nico, and Andy Warhol. As with any major rock group, however, there

were dozens of figures making significant contributions to their

evolution that are generally overlooked, undercredited, or even

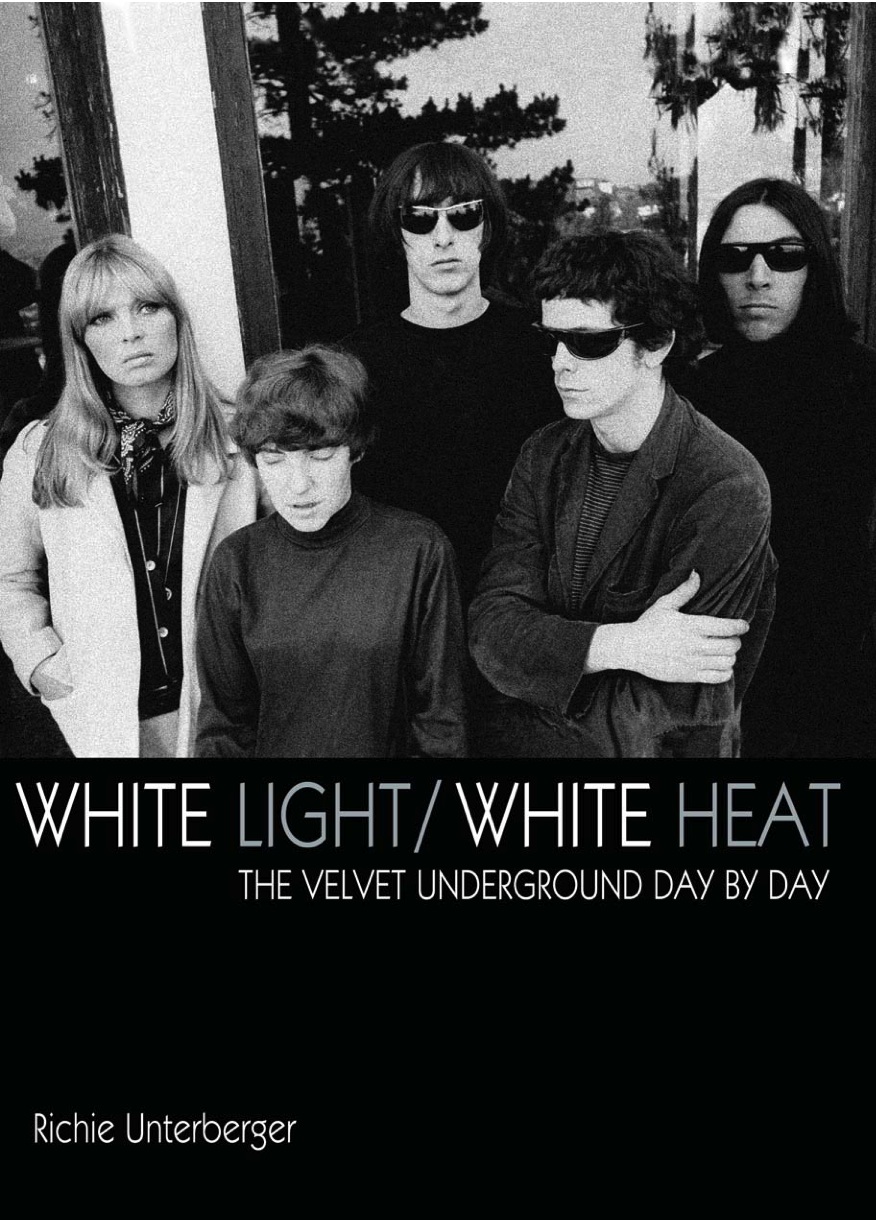

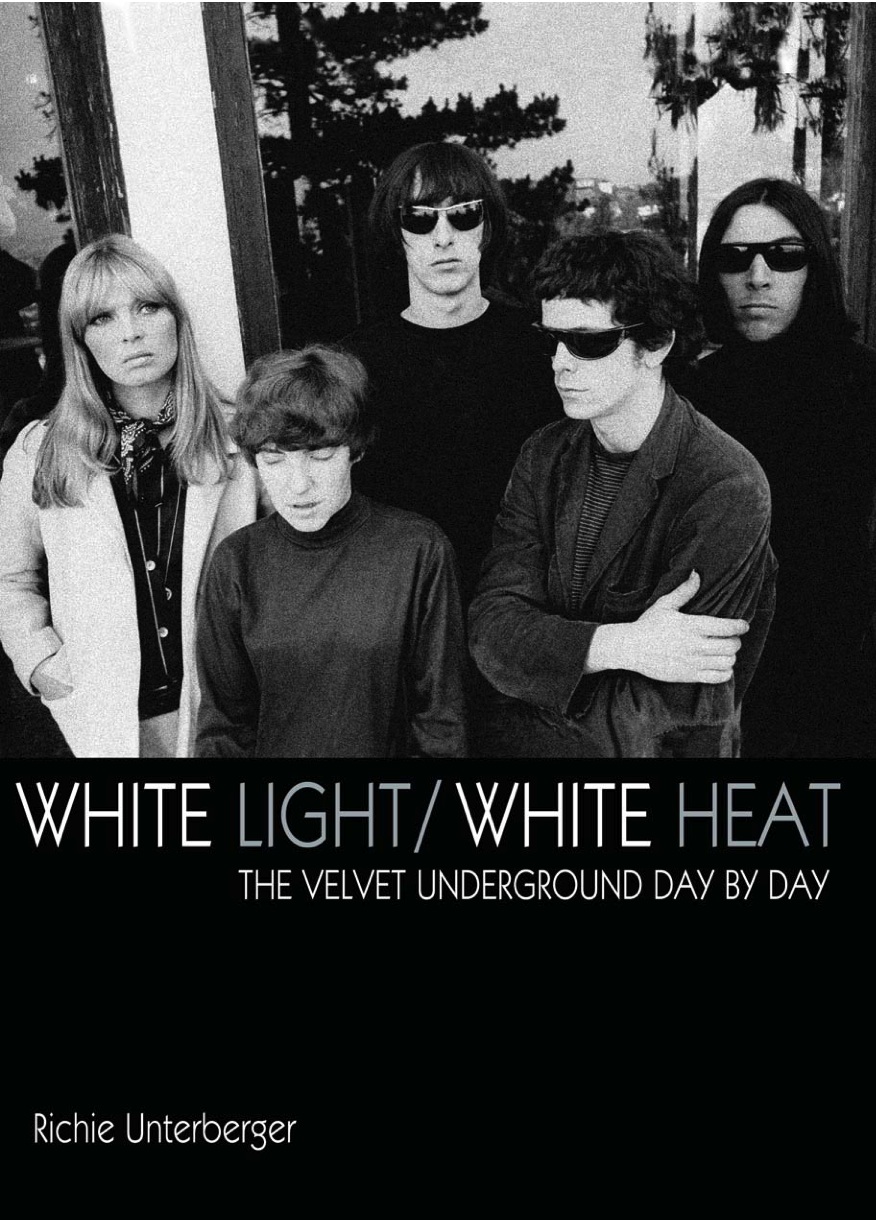

virtually unknown to the larger public. White Light/White Heat: The Velvet

Underground Day-By-Day discusses

many of them. Here's a brief guide to some

of the most notable:

Doug Yule: Many would find it

strange to classify a full-time member of the Velvet Underground from

October 1968 to mid-1973 as someone who's overlooked or obscure.

Consider, however, that several film documentaries covering the Velvets

fail to even mention Yule's name. Consider, too, that he was not

inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with Lou Reed, John Cale,

Sterling Morrison, and Maureen Tucker when the Velvet Underground were

admitted to that institution in 1996, although he actually plays on

more commercially released Velvet Underground recordings than Cale

does, even discounting the post-1970 recordings made without Reed in

the band.

More important than the quantity of Yule's work, however, is its

underrated quality. While not the idiosyncratic talent that Cale was as

an instrumentalist and singer-songwriter, Yule was a fine bassist who

quickly and adeptly eased the group's transition to a more powerful, if

more conventional, rock sound. It's also overlooked that he made

significant contributions as a multi-instrumentalist, also playing

organ with the group onstage—that's his electrifying swirl on the 1969 Velvet Underground Live

version of "What Goes On"—and also chipping in on keyboards, drum,

guitar, backup vocals, arrangements, and the occasional lead vocal

("Candy Says" being the standout) in the studio and in concert. Far

from being an incidental, faceless entity needed to fill out the

lineup, as some accounts might have you believe, Yule was not just an

adequate replacement—he was a very considerable asset to the group.

Angus MacLise: Although he was

the group's original drummer and a full member of the Velvet

Underground for much of 1965, there's a good reason why the name of

Angus MacLise isn't familiar, even to many VU fans. He doesn't appear

on any of their commercially released recordings (although he can be heard on the versions of

"Heroin" and "Venus in Furs" on the soundtrack of the short film Andy Warhol's Exploding Plastic Inevitable,

shot at the Velvet Underground's performances in Chicago in mid-1966,

during which MacLise temporarily rejoined the lineup to help cover for

an ill Lou Reed's absence). Nor did he go on to fame in any other

capacity, or even release any music in his lifetime other than an

obscure flexidisc, though several CDs of his recordings have come out

posthumously.

Still, MacLise's idiosyncratic percussive style—sometimes likened to

the sound of falling rain, and incorporating world music influences

from his travels in the Far East—helped shape the avant-garde aesthetic

that immediately set the Velvet Underground apart from other rock bands

when they formed in 1965. MacLise also supplied voltage for their

electric guitars in their very early days, the band running extension

cords between their apartments through the hall in 56 Ludlow Street on

New York's Lower East Side. Not incidentally, both Hetty MacLise (whom

Angus married in the late 1960s) and Terry Riley, both of whom later

worked with Angus in settings outside the Velvets, feel in retrospect

that Angus's experience as a poet was influential upon the nature of

the material the group developed.

Paul Morrissey: Ask most

people who managed the Velvet Underground, and their answer will be

Andy Warhol. That's only partially true. Though Warhol was indeed

involved in their management from the beginning of 1966 through around

mid-1967, technically speaking he co-managed them with Paul Morrissey,

a filmmaker who himself managed Warhol. It should also be noted that

the Velvets were briefly managed by Al Aronowitz (though he didn't bind

them to a legal agreement) in late 1965 before meeting Warhol, and that

Steve Sesnick would take control of their affairs from mid-1967 through

their demise in the early 1970s.

Morrissey said in his interview for White

Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day By Day that many of

the ideas often credited to Andy originated from Morrissey himself. As

for Warhol's direct involvement with the functions usually associated

with a rock manager—getting them gigs, dealing with record labels,

dealing with the logistics of their stage show, and so forth—certainly

Morrissey was more involved than Andy was. According to Paul, "In

actual reality, the basis of these things came almost always from me,

and not from him, during these years I was there. I'm the one that met

them, told them I would manage them, put Nico in the group, and Andy

would present them, be called the manager. But have you ever heard of a

manager who had a manager?

I'd love for you to come up with another situation where there was

somebody who was a manager who had a manager who told him what things

should be done and then went and did them himself."

Steve Sesnick: Unlike Andy

Warhol, Paul Morrissey, or even Al Aronowitz, Steve Sesnick is not

renowned for anything other than managing the Velvet Underground. Too,

he's often cast as a villainous character for sowing discord within the

band, both Lou Reed and John Cale calling him a "snake" in different

interviews after they left the Velvets. In particular, Cale has felt

that Sesnick tried to push Reed as the band's leader at the expense of

group harmony, and Sesnick's pressure to live up to certain

expectations and images has been cited as a key factor in Reed's

departure from the band in August 1970. "The real snake is a guy named

Steve Sesnick," said Reed in the November 1987 issue of Creem. "He was a very bad person,

trying to divide everyone, telling one person one thing, telling

another person something else, and pitting people against each other,

starting with John and me, and then working his way down through the

band. That way he could maintain power. I quit in the middle of Loaded because I couldn't stand it

anymore."

There's usually a different side to every story, and while defending

Sesnick's overall performance isn't an enviable task, it should be said

that he did do a lot for the

Velvets in certain respects. He took on a very uncommercial band and

worked hard on their behalf, helping them in their transition from

their role as part of Andy Warhol's Exploding Plastic Inevitable into a

standalone rock act that toured nationally in prominent venues. Doug

Yule has said Sesnick did a lot to extract financial support from MGM,

the band's label before 1970, at a time when the Velvets weren't

selling that many records.

"He tended to, let us say, exaggerate or elaborate upon the truth,"

says Steve Nelson, who dealt with Sesnick on numerous occasions over

the next few years as manager of the Boston Tea Party and a promoter at

venues where the band played elsewhere in Massachusetts. "So sometimes

it was hard to know what was the truth about what he was really saying.

I think that that was one of his weaknesses, although he used it as a

strength in terms of as a promoter, talking his way into people. He

always had a good patter.

"His strength was, he was really dedicated to the band. He wasn't there

as some music-biz guy to kind of exploit them. 'Cause first of all, it

wasn't really like a huge commercial opportunity. There was a part of

him that came from his heart, in terms of really being committed to the

Velvet Underground. When they booked, they showed. He got them there.

And that wasn't always true with people that we booked in those days.

Sometimes things got pretty flaky. But I never had any problems with

him in that regard. In terms of business dealings, he was pretty

straightforward. I booked them a lot, and he never let me down once."

Tom Wilson: The Verve/MGM

executive who signed the Velvet Underground, when every other label

they had approached—definitely including Columbia, and according to

Sterling Morrison, also including Atlantic and Elektra—had turned them

down. He also produced their second album, White Light/White Heat, and though

he's only credited as the producer of one track ("Sunday Morning") on The Velvet Underground & Nico

(with Andy Warhol credited as producer of record for the rest of the

LP), it's been speculated that Wilson might have been the actual

producer of the May 1966 Los Angeles recordings of "Heroin," "Venus in

Furs," and "I'm Waiting for the Man" that are used on the record.

The depth of Wilson's actual contributions to the 1966-67 VU recordings

has been questioned. It's been recalled that, for the VU sessions and

those of some other bands he produced, he'd spend much of his time on

the phone with girlfriends. According to Paul Morrissey, he primarily

signed the Velvets because of Nico, feeling she was the only commercial

aspect of the band. But as John Cale told Creem in 1987, "He was inspired,

though, and used to joke around to keep everybody in the band light."

And Lewis Merenstein—a close friend of Wilson's who first worked with

Tom as an engineer back when the producer broke into the record

business in the mid-1950s, and co-produced Cale's first solo LP—feels

Wilson would have given the Velvets "freedom and enthusiasm. Tom did

not have a heavy hand. He wanted people to be who they were. He got

along with everybody. He was truly a free spirit."

In his very distinguished career, Wilson also produced Bob Dylan, Simon

& Garfunkel, the Mothers of Invention, the Animals, the Soft

Machine, Dion, John Coltrane, Sun Ra, and Cecil Taylor.

Norman Dolph: The Columbia

Records sales executive who co-financed the April 1966 sessions at

Scepter Records Studios in New York that produced the bulk of the

banana album. In essence he was a co-producer of sorts for the sessions

themselves as well, acting much more in that traditional capacity than

Andy Warhol did, though Warhol and not Dolph would be officially

credited as the producer of the tracks on the LP. Dolph also used an

acetate made from these sessions to try and get the group a deal with

Columbia, but was immediately and forcefully turned down. (One of the

acetates made from the sessions would sell on eBay for about $25,000

about 40 years later, marking one of the highest prices ever paid for a

music disc.)

John Licata: The engineer for

the April 1966 sessions at Scepter Records. Licata "was a wonderful,

cooperative, easy to get along with, unfreaky guy," observes Dolph. "He

was the total antithesis of the Velvet Underground. At no time did any

of the musicians ever tell him what to do. They went in and played, and

he got what they wanted. On the banana album, they credit Val Valentin

with the engineering. He may have done much of the remix or whatever,

but he's certainly not the engineer that was responsible for the sound

of the album at its basis. When I heard the banana album [a year

later], it sounded to me just like what we did. It didn't sound

appreciably different from what we did at Scepter."

Tony Conrad: Now well known in

his own right as an experimental musician and filmmaker, Conrad played

with John Cale in La Monte Young's group from late 1963 to late 1965.

With Cale, he was instrumental in developing that group's jet-strength

amplified drone on stringed instruments—a quality that Cale was in turn

instrumental in bringing into the Velvet Underground. Conrad also

played alongside Cale and Lou Reed briefly in late 1964 and early 1965

live in the rock band the Primitives, and according to most accounts

found the book lying on a New York street, The Velvet Underground, that the

band named themselves after.

La Monte Young: One of the most

esteemed avant-garde composer/musicians of the twentieth century, in

whose group Conrad and Cale played, as did Angus MacLise, who played

with Young for various periods between 1962 and 1965.

Walter De Maria: Drummer in the

Primitives, the pre-VU band also including Lou Reed, John Cale, and

Tony Conrad, playing several concerts in late 1964/early 1965. De Maria

had also played in a rock group that briefly existed in 1963 which also

included La Monte Young and none other than Andy Warhol.

Terry Philips: The Pickwick

Records producer who signed Lou Reed to the label as a staff songwriter

in late 1964, getting credited (along with other writers) alongside

Reed for composing numerous mid-'60s Pickwick releases. The most

noteworthy of these is "The Ostrich," the late 1964 single credited to

the Primitives on which Lou Reed takes lead vocal.

Some accounts would have it that Philips and Pickwick stifled Reed's

creativity, and particularly discouraged the recording of controversial

songs like "Heroin." But in his interview for White Light/White Heat: The Velvet

Underground Day By Day, Philips repeatedly stated his admiration

for Reed's talents and regrets that he and Pickwick couldn't have

worked with him more. "I helped encourage him on his writing to do

things that were more like 'Heroin,' and more like the kind of writing

he did in short stories," he stated. "We were working towards a goal. I

thought he could be what he became." It's also worth noting that Reed

was not the only hip musician whose path Philips crossed, as Terry had

also worked with Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller, and Phil Spector. He would

also record free jazz musicians Sunny Murray, Albert Ayler, Pharoah

Sanders, and Larry Young, and be a partner at one point with renowned

writer LeRoi Jones in a jazz label.

Delmore Schwartz: The

acclaimed short story writer (most famous for "In Dreams Begin

Responsibilities") and novelist was a professor to Lou Reed at Syracuse

University, helping to inspire Reed's own writing. In the songwriting

credits for The Velvet Underground

& Nico, "European Son" is titled "European Son to Delmore

Schwartz." It's somewhat of a tongue-in-cheek dedication, however;

knowing Schwartz's aversion to rock lyrics, the group chose the song

with the least words to name in his honor. "Delmore despised rock and

roll lyrics, he thought they were ridiculous and awful, and 'European

Son' has hardly any lyrics so that meant that was a song that Delmore

might like," explained Sterling Morrison in his 1986 interview with

Ignacio Julia for Spanish television. "He didn't care about the music

part of rock and roll, he just hated the lyrics, so we wrote a song

that Delmore would like: twenty seconds of lyrics and seven minutes of

noise."

Piero Heliczer: Experimental

filmmaker, and longtime friend of Angus MacLise, at whose multimedia

events or "happenings" the Velvet Underground played some of their

first shows in 1965. It's clear these "happenings" had a big effect on

Sterling Morrison, who wrote in the literary magazine Little Caesar, "For me the path

ahead became suddenly clear. I could work on music different from

ordinary rock'n'roll since Piero had given Lou, John, Angus and me a

context to perform it in."

Kate Heliczer: Then-wife of

Piero Heliczer, she circulated demos of the Velvet Underground in

Britain in 1965 and 1966 in an attempt to help them find management

and/or a record deal.

Al Aronowitz: New York Post reporter who was

among the first journalists to take rock seriously, introducing the

Beatles to Bob Dylan in 1964. While dabbling in rock management, he

handled the Velvet Underground for a month or two near the end of 1965,

though as he didn't sign them to a contract, it was easy for the group

to leave him in favor of Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey. The late

Aronowitz's highly opinionated account of his stint with the Velvets

can be read at http://www.bigmagic.com/pages/blackj/column80.html.

Barbara Rubin: The young

experimental filmmaker and friend of Allen Ginsberg who urged Al

Aronowitz to take on the Velvet Underground in late 1965, and then

urged Gerard Malanga to see the Velvets in December of that year at the

Café Bizarre in Greenwich Village. That in turn led to Paul

Morrissey and Andy Warhol seeing the Velvets at the club and offering

to manage the group.

Henry Flynt: Experimental

musician who, like John Cale, had circulated in the New York

avant-garde scene of the early-to-mid-'60s with the likes of Tony

Conrad and La Monte Young. In September 1966, he filled in for Cale for

four Velvet Underground performances at the Balloon Farm in New York.

Though a few other musicians are known to have sat in informally with

the Velvets in 1965 and 1966 (including Piero Heliczer, Helen Byrne,

Richard Mishkin, and Bobby Ritchkin), Flynt's brief run seems to have

been the most extensive such stint.

Edie Sedgwick: A dancer at some

of the Velvets' very earliest performances after they hooked up with

Warhol in early 1966. By most accounts she severed her contact with

Warhol and the Factory, and thus the VU, in February of 1966. As much

attention as she gets these days for her relationship to Warhol and the

Factory, her role in the Velvet Underground story is very slight,

though it does include a brief romantic relationship with John Cale for

a few weeks in early '66.

Gerard Malanga: Andy Warhol

assistant and poet/photographer/filmmaker who was perhaps the most

renowned of the dancers of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable,

particularly for doing a "whip dance." Some have speculated that his

dress and image influenced Jim Morrison of the Doors.

Mary Woronov: Another EPI

dancer, frequently enacting routines with Malanga, and subsequently an

acclaimed film director.

Danny Williams: Sometimes

credited with handling lights at the EPI shows, disappearing on July

25, 1966 in an incident that's often been thought to have been a

suicide. His story is told, and excerpts from his films shown, in the

2007 documentary A Walk into the Sea,

directed by his niece, Esther Robinson. The movie also includes brief

silent snippets of the Velvet Underground rehearsing in early 1966 that

were shot by Williams, taken from footage that lasts about fifteen to

twenty minutes altogether. For the record, Paul Morrissey maintains

that Williams "didn't have do anything to do with any lights or the

Plastic Inevitable; that was done entirely by me. There was no light

show other than the five film projections, five slide projections, and

one spotlight that was used in a mirror ball that revolved. We didn't

need any other lights, nor could we afford them; there was no place to

put them or anyone to work them."

Eric Emerson: Another EPI

dancer, as well as sometime Nico boyfriend and actor (alongside Nico

and her son Ari) in the film The

Chelsea Girls. Sometimes regarded as one of the chief villains

of the Velvet Underground story for threatening legal action for use of

his photo (in a projection at an EPI performance) on the back of The Velvet Underground & Nico,

causing the album to be withdrawn from distribution for a while and

helping to kill whatever commercial momentum it might have gathered.

Billy Name: Important part of

the Factory who took the pictures for the covers of both White Light/White Heat and The Velvet Underground.

Ron Nameth: Filmmaker who shot

the 1966 short film Andy Warhol's

Exploding Plastic Inevitable during the Velvet Underground's

performances in Chicago in mid-1966. Although Lou Reed and Nico were

missing from these performances (for which original drummer Angus

MacLise temporarily rejoined the group), and although the Velvets can

only be seen briefly (though they're heard on the soundtrack), this is

the most comprehensive on-screen document of the Exploding Plastic

Inevitable.

Ari Delon: Nico's son (and only

child, usually considered to have been conceived with star French actor

Alain Delon), who appears with the Velvets in Andy Warhol's movie The Velvet Underground: A Symphony of Sound,

shot at the Factory in early 1966.

Charlie Rothschild: Booked

shows for the Velvet Underground in California in May 1966, and again

in September-October 1966 at the Balloon Farm in New York.

Gary Kellgren: Engineer on many

of the Velvet Underground's late-1960s recordings. More renowned as an

engineer on some of Jimi Hendrix's recordings, and as co-founder of the

Record Plant recording studios in New York City, which the Velvets

sometimes used.

Hans Onsager: Road manager for

the Velvet Underground in the late 1960s, and son of Lars Onsager,

winner of the 1968 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Steve Nelson: Manager of the

Boston Tea Party, the Velvet Underground's favorite venue, in the late

1960s, subsequently frequently booking the Velvets (at a time where

they were in definite need of the work) at several clubs he operated in

the state of Massachusetts.

Vic Briggs: Formerly guitarist

with Eric Burdon and the Animals, he tried to produce the Velvet

Underground for a few nights in late 1968 at the sessions for their

third LP before it was mutually decided that it wasn't working out.

Billy Yule: Drummer for the

Velvet Underground for their two-month stint at Max's Kansas City in

New York between late June and late August of 1970, playing on the Live at Max's Kansas City album and

some of the recordings used on Loaded.

Other members have since expressed regret that they didn't wait until a

pregnant Maureen Tucker had given birth and was ready to resume her

place in the band before recording Loaded, and Billy Yule's more

conventional rock style wasn't as suited for the group as Tucker's more

idiosyncratic one. But Billy was there to fill the drum chair in summer

1970 at both one of their most important long-running gigs and some of

the sessions for their final studio album with Lou Reed, and for that,

his contributions can't be discounted.

Ahmet Ertegun: Signed the

Velvet Underground to Atlantic Records in early 1970, enabling them to

escape an unsatisfactory situation with MGM and make a more

professionally recorded album, Loaded,

than any of their previous efforts. Ertegun and Atlantic would

subsequently be criticized by some band members, however, for failing

to promote Loaded well,

failing to give the Reed-less band an opportunity to record a follow-up

studio album, and for issuing a live LP (Live at Max's Kansas City) with the

Reed lineup that had bootleg-quality sound. Sterling Morrison has also

said that Ertegun and Atlantic were among the parties to reject the

Velvet Underground when they were shopping for a record deal in early

1966.

Tommy Castanaro: A real mystery

man, this Long Island session drummer, probably recruited through the

Musicians Union, appears on a couple tracks on Loaded.

Adrian Barber: Co-engineer and

co-producer of Loaded, also

playing some drums at the sessions. He also worked with Cream, the Bee

Gees, and the Allman Brothers. A former member of the Liverpool group

the Big Three, way back in December 1962, he'd also made lo-fi live

tapes of the Beatles that were released almost 15 years later as Live! At the Star-Club in Hamburg, Germany.

Geoff Haslam: Another English

co-producer/co-engineer on Loaded,

his most famous other credit being producing the MC5's High Time album.

Shel Kagan: The least

celebrated of Loaded's three

producers.

Robert Somma: Editor of

Boston-based, nationally-distributed rock magazine Fusion who, though rarely credited,

was perhaps the journalist who did more than any other (with the

possible exception of Richard Williams in the UK) to raise the Velvet

Underground's visibility in the rock press in the late 1960s and early

1970s, championing them via pieces in Fusion

and other publications.

Jonathan Richman: Perhaps the

VU's most fanatical fan, seeing them many times in Boston and elsewhere

as a teenager, and becoming one of the first important Velvet

Underground-influenced musicians as leader of the (occasionally John

Cale-produced) Modern Lovers in the early 1970s.

Richard Williams: The

journalist who did more than any other to popularize the Velvet

Underground in the British rock press in the late 1960s and early

1970s, especially via rave reviews in Melody

Maker. Later to sign John Cale and Nico to Island Records, and

currently chief sportswriter at the UK national paper The Guardian.

Danny Fields: Atlantic Records

publicist who helped arrange for the sale and release of the August 23,

1970 tapes issued on Live at Max's

Kansas City.

Brigid Berlin (aka Brigid Polk):

Andy Warhol Factory worker and actress who tapes the Velvet Underground

at Max's Kansas City on August 23, 1970, their final night before Lou

Reed left the band. These are the tapes later issued on the LP and

expanded CD versions of Live at

Max's Kansas City.

Richard & Lisa Robinson: Husband

and wife who were instrumental in encouraging Lou Reed to begin a solo

career after his exit from the Velvet Underground, with Richard

Robinson producing Reed's debut solo LP in early 1972.

Paul Nelson: Mercury A&R

man whose idea it was to compile and issue the two-LP set 1969 Velvet Underground Live, one

of the greatest live rock albums ever, in 1974, when such lengthy

archive concert releases of cult bands are virtually unknown.

Elliott Murphy:

Singer-songwriter who helped compile 1969

Velvet Underground Live, and wrote the LP's liner notes.

Patti Smith: The first star

punk/new wave musician to help retroactively popularize the Velvet

Underground, not only via their incorporation of the group's influence

on her John Cale-produced 1975 debut LP, but also by covering some of

their songs in concert. Prior to her recording debut, she also wrote

rave reviews of the Velvet Underground rock critic, as did her

guitarist, Lenny Kaye.

M.C. Kostek & Phil Milstein:

Editors of the Velvet Underground fanzine What Goes On, the organization that

did more than any other to spread the growth of the group's cult after

their dissolution.

unless otherwise specified.

HOME

WHAT'S NEW

MUSIC BOOKS

MUSIC REVIEWS TRAVEL

BOOKS

LINKS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SITE MAP

EMAIL RICHIE

BUY BOOKS